Dynamic Expression and Essential Functions of Hes7 in Somite Segmentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regulation of Cardiac Progenitors by Combination of Mesp1 and ETS

REGULATION OF CARDIAC PROGENITORS BY COMBINATION OF MESP1 AND ETS TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS A Dissertation by KUO-CHAN WENG Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Fen Wang Co-Chair of Committee, Robert J. Schwartz Committee Members, James F. Martin Jiang Chang Head of Department, Fen Wang May 2014 Major Subject: Medical Science Copyright 2014 Kuo-Chan Weng ABSTRACT Heart disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide. By understanding the regulating networks during cardiac development we can exploit those networks to manipulate adult cells into cardiac progenitors and provide an alternative for repairing diseased hearts. Mesp1 is considered to have critical roles during cardiac development but the molecular mechanisms need to be further studied. The roles of ETS transcription factors have been primarily limited to hematopoietic differentiation and cancer progression. The ETS transcription factors are known to have proliferating roles and were hypothesized to also be involved in cardiac differentiation and may potentially be used for cell reprogramming. The first part of this study characterizes the expression pattern of Mesp1 protein in early mouse embryo from E6.5 to E9.5 and provides a full expression profile in differentiating embryoid bodies in vitro from the undifferentiated stage to Day10. Our work showed Mesp1 expresses in the posterior region of E6.5 embryo then starts migrating through the primitive streak toward anterior mesoderm and endoderm in E7.5. A Mesp1 linage tracing ES cell line was established, and it allowed us to trace the Mesp1 derived cell population. -

Detailed Review Paper on Retinoid Pathway Signalling

1 1 Detailed Review Paper on Retinoid Pathway Signalling 2 December 2020 3 2 4 Foreword 5 1. Project 4.97 to develop a Detailed Review Paper (DRP) on the Retinoid System 6 was added to the Test Guidelines Programme work plan in 2015. The project was 7 originally proposed by Sweden and the European Commission later joined the project as 8 a co-lead. In 2019, the OECD Secretariat was added to coordinate input from expert 9 consultants. The initial objectives of the project were to: 10 draft a review of the biology of retinoid signalling pathway, 11 describe retinoid-mediated effects on various organ systems, 12 identify relevant retinoid in vitro and ex vivo assays that measure mechanistic 13 effects of chemicals for development, and 14 Identify in vivo endpoints that could be added to existing test guidelines to 15 identify chemical effects on retinoid pathway signalling. 16 2. This DRP is intended to expand the recommendations for the retinoid pathway 17 included in the OECD Detailed Review Paper on the State of the Science on Novel In 18 vitro and In vivo Screening and Testing Methods and Endpoints for Evaluating 19 Endocrine Disruptors (DRP No 178). The retinoid signalling pathway was one of seven 20 endocrine pathways considered to be susceptible to environmental endocrine disruption 21 and for which relevant endpoints could be measured in new or existing OECD Test 22 Guidelines for evaluating endocrine disruption. Due to the complexity of retinoid 23 signalling across multiple organ systems, this effort was foreseen as a multi-step process. -

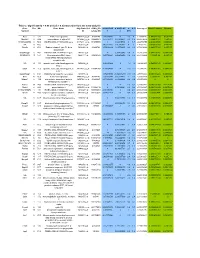

Table 2. Significant

Table 2. Significant (Q < 0.05 and |d | > 0.5) transcripts from the meta-analysis Gene Chr Mb Gene Name Affy ProbeSet cDNA_IDs d HAP/LAP d HAP/LAP d d IS Average d Ztest P values Q-value Symbol ID (study #5) 1 2 STS B2m 2 122 beta-2 microglobulin 1452428_a_at AI848245 1.75334941 4 3.2 4 3.2316485 1.07398E-09 5.69E-08 Man2b1 8 84.4 mannosidase 2, alpha B1 1416340_a_at H4049B01 3.75722111 3.87309653 2.1 1.6 2.84852656 5.32443E-07 1.58E-05 1110032A03Rik 9 50.9 RIKEN cDNA 1110032A03 gene 1417211_a_at H4035E05 4 1.66015788 4 1.7 2.82772795 2.94266E-05 0.000527 NA 9 48.5 --- 1456111_at 3.43701477 1.85785922 4 2 2.8237185 9.97969E-08 3.48E-06 Scn4b 9 45.3 Sodium channel, type IV, beta 1434008_at AI844796 3.79536664 1.63774235 3.3 2.3 2.75319499 1.48057E-08 6.21E-07 polypeptide Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RIKEN cDNA 2310040G17 gene 1417619_at 4 3.38875643 1.4 2 2.69163229 8.84279E-06 0.0001904 BC056474 15 12.1 Mus musculus cDNA clone 1424117_at H3030A06 3.95752801 2.42838452 1.9 2.2 2.62132809 1.3344E-08 5.66E-07 MGC:67360 IMAGE:6823629, complete cds NA 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1454696_at -3.46081884 -4 -1.3 -1.6 -2.6026947 8.58458E-05 0.0012617 beta 1 Gnb1 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1417432_a_at H3094D02 -3.13334396 -4 -1.6 -1.7 -2.5946297 1.04542E-05 0.0002202 beta 1 Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RAD23a homolog (S. -

Watsonjn2018.Pdf (1.780Mb)

UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL OKLAHOMA Edmond, Oklahoma Department of Biology Investigating Differential Gene Expression in vivo of Cardiac Birth Defects in an Avian Model of Maternal Phenylketonuria A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN BIOLOGY By Jamie N. Watson Edmond, OK June 5, 2018 J. Watson/Dr. Nikki Seagraves ii J. Watson/Dr. Nikki Seagraves Acknowledgements It is difficult to articulate the amount of gratitude I have for the support and encouragement I have received throughout my master’s thesis. Many people have added value and support to my life during this time. I am thankful for the education, experience, and friendships I have gained at the University of Central Oklahoma. First, I would like to thank Dr. Nikki Seagraves for her mentorship and friendship. I lucked out when I met her. I have enjoyed working on this project and I am very thankful for her support. I would like thank Thomas Crane for his support and patience throughout my master’s degree. I would like to thank Dr. Shannon Conley for her continued mentorship and support. I would like to thank Liz Bullen and Dr. Eric Howard for their training and help on this project. I would like to thank Kristy Meyer for her friendship and help throughout graduate school. I would like to thank my committee members Dr. Robert Brennan and Dr. Lilian Chooback for their advisement on this project. Also, I would like to thank the biology faculty and staff. I would like to thank the Seagraves lab members: Jailene Canales, Kayley Pate, Mckayla Muse, Grace Thetford, Kody Harvey, Jordan Guffey, and Kayle Patatanian for their hard work and support. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

BMP Signaling Orchestrates a Transcriptional Network to Control the Fate of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (Mscs)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/104927; this version posted February 1, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. BMP signaling orchestrates a transcriptional network to control the fate of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) Jifan Feng1, Junjun Jing1,2, Jingyuan Li1, Hu Zhao1, Vasu Punj3, Tingwei Zhang1,2, Jian Xu1 and Yang Chai1,* 1Center for Craniofacial Molecular Biology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90033, USA 2State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China 3Department of Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA *Corresponding author: Yang Chai 2250 Alcazar Street – CSA 103 Center for Craniofacial Molecular Biology University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA Phone number: 323-442-3480 [email protected] Running Title: BMP regulates cell fate of MSCs Key Words: BMP, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), odontogenesis, Gli1 Summary Statement: BMP signaling activity is required for the lineage commitment of MSCs and transcription factors downstream of BMP signaling may determine distinct cellular identities within the dental mesenchyme. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/104927; this version posted February 1, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. -

Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis of KRAS Mutant Cell Lines Ben Yi Tew1,5, Joel K

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of KRAS mutant cell lines Ben Yi Tew1,5, Joel K. Durand2,5, Kirsten L. Bryant2, Tikvah K. Hayes2, Sen Peng3, Nhan L. Tran4, Gerald C. Gooden1, David N. Buckley1, Channing J. Der2, Albert S. Baldwin2 ✉ & Bodour Salhia1 ✉ Oncogenic RAS mutations are associated with DNA methylation changes that alter gene expression to drive cancer. Recent studies suggest that DNA methylation changes may be stochastic in nature, while other groups propose distinct signaling pathways responsible for aberrant methylation. Better understanding of DNA methylation events associated with oncogenic KRAS expression could enhance therapeutic approaches. Here we analyzed the basal CpG methylation of 11 KRAS-mutant and dependent pancreatic cancer cell lines and observed strikingly similar methylation patterns. KRAS knockdown resulted in unique methylation changes with limited overlap between each cell line. In KRAS-mutant Pa16C pancreatic cancer cells, while KRAS knockdown resulted in over 8,000 diferentially methylated (DM) CpGs, treatment with the ERK1/2-selective inhibitor SCH772984 showed less than 40 DM CpGs, suggesting that ERK is not a broadly active driver of KRAS-associated DNA methylation. KRAS G12V overexpression in an isogenic lung model reveals >50,600 DM CpGs compared to non-transformed controls. In lung and pancreatic cells, gene ontology analyses of DM promoters show an enrichment for genes involved in diferentiation and development. Taken all together, KRAS-mediated DNA methylation are stochastic and independent of canonical downstream efector signaling. These epigenetically altered genes associated with KRAS expression could represent potential therapeutic targets in KRAS-driven cancer. Activating KRAS mutations can be found in nearly 25 percent of all cancers1. -

Supplementary Figure S4

18DCIS 18IDC Supplementary FigureS4 22DCIS 22IDC C D B A E (0.77) (0.78) 16DCIS 14DCIS 28DCIS 16IDC 28IDC (0.43) (0.49) 0 ADAMTS12 (p.E1469K) 14IDC ERBB2, LASP1,CDK12( CCNE1 ( NUTM2B SDHC,FCGR2B,PBX1,TPR( CD1D, B4GALT3, BCL9, FLG,NUP21OL,TPM3,TDRD10,RIT1,LMNA,PRCC,NTRK1 0 ADAMTS16 (p.E67K) (0.67) (0.89) (0.54) 0 ARHGEF38 (p.P179Hfs*29) 0 ATG9B (p.P823S) (0.68) (1.0) ARID5B, CCDC6 CCNE1, TSHZ3,CEP89 CREB3L2,TRIM24 BRAF, EGFR (7p11); 0 ABRACL (p.R35H) 0 CATSPER1 (p.P152H) 0 ADAMTS18 (p.Y799C) 19q12 0 CCDC88C (p.X1371_splice) (0) 0 ADRA1A (p.P327L) (10q22.3) 0 CCNF (p.D637N) −4 −2 −4 −2 0 AKAP4 (p.G454A) 0 CDYL (p.Y353Lfs*5) −4 −2 Log2 Ratio Log2 Ratio −4 −2 Log2 Ratio Log2 Ratio 0 2 4 0 2 4 0 ARID2 (p.R1068H) 0 COL27A1 (p.G646E) 0 2 4 0 2 4 2 EDRF1 (p.E521K) 0 ARPP21 (p.P791L) ) 0 DDX11 (p.E78K) 2 GPR101, p.A174V 0 ARPP21 (p.P791T) 0 DMGDH (p.W606C) 5 ANP32B, p.G237S 16IDC (Ploidy:2.01) 16DCIS (Ploidy:2.02) 14IDC (Ploidy:2.01) 14DCIS (Ploidy:2.9) -3 -2 -1 -3 -2 -1 -3 -2 -1 -3 -2 -1 -3 -2 -1 -3 -2 -1 Log Ratio Log Ratio Log Ratio Log Ratio 12DCIS 0 ASPM (p.S222T) Log Ratio Log Ratio 0 FMN2 (p.G941A) 20 1 2 3 2 0 1 2 3 2 ERBB3 (p.D297Y) 2 0 1 2 3 20 1 2 3 0 ATRX (p.L1276I) 20 1 2 3 2 0 1 2 3 0 GALNT18 (p.F92L) 2 MAPK4, p.H147Y 0 GALNTL6 (p.E236K) 5 C11orf1, p.Y53C (10q21.2); 0 ATRX (p.R1401W) PIK3CA, p.H1047R 28IDC (Ploidy:2.0) 28DCIS (Ploidy:2.0) 22IDC (Ploidy:3.7) 22DCIS (Ploidy:4.1) 18IDC (Ploidy:3.9) 18DCIS (Ploidy:2.3) 17q12 0 HCFC1 (p.S2025C) 2 LCMT1 (p.S34A) 0 ATXN7L2 (p.X453_splice) SPEN, p.P677Lfs*13 CBFB 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 -

The Regulation of Lunatic Fringe During Somitogenesis

THE REGULATION OF LUNATIC FRINGE DURING SOMITOGENESIS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Emily T. Shifley ***** The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Susan Cole, Advisor Professor Christine Beattie _________________________________ Professor Mark Seeger Advisor Graduate Program in Molecular Genetics Professor Michael Weinstein ABSTRACT Somitogenesis is the morphological hallmark of vertebrate segmentation. Somites bud from the presomitic mesoderm (PSM) in a sequential, periodic fashion and give rise to the rib cage, vertebrae, and dermis and muscles of the back. The regulation of somitogenesis is complex. In the posterior region of the PSM, a segmentation clock operates to organize cohorts of cells into presomites, while in the anterior region of the PSM the presomites are patterned into rostral and caudal compartments (R/C patterning). Both of these stages of somitogenesis are controlled, at least in part, by the Notch pathway and Lunatic fringe (Lfng), a glycosyltransferase that modifies the Notch receptor. To dissect the roles played by Lfng during somitogenesis, we created a novel allele that lacks cyclic Lfng expression within the segmentation clock, but that maintains expression during R/C somite patterning (Lfng∆FCE1). Lfng∆FCE1/∆FCE1 mice have severe defects in their anterior vertebrae and rib cages, but relatively normal sacral and tail vertebrae, unlike Lfng knockouts. Segmentation clock function is differentially affected by the ∆FCE1 deletion; during anterior somitogenesis the expression patterns of many clock genes are disrupted, while during posterior somitogenesis, certain clock components have recovered. R/C patterning occurs relatively normally in Lfng∆FCE1/∆FCE1 embryos, likely contributing to the partial phenotype rescue, and confirming that Lfng ii plays separate roles in the two regions of the PSM. -

NKX2-8 Antibody (Pab)

21.10.2014NKX2-8 antibody (pAb) Rabbit Anti -Human/Mouse/Rat NK2 homeobox 8 (NKXH, NKX2 -9) Instruction Manual Catalog Number PK-AB718-6753 Synonyms NKX2-8 Antibody: NK2 homeobox 8, NKXH, NKX2-9 Description NKX2-8 (NK2 homeobox 8) is a member of a family of transcription factors that are involved in embryonic development and cell fate. It is expressed in the ventral foregut, the developing heart, the epithelial layers of the branchial arches and in the dorsal mesoderm. In conjunction with related protein, NKX2-5, NKX2-8 may play a role in cardiac embryonic development. NKX2-8 is also thought to be involved in lung development and is suspected of being an oncogene in lung cancer that is activated by way of gene amplification at chromosome 14q13. Quantity 100 µg Source / Host Rabbit Immunogen NKX2-8 antibody was raised against a 19 amino acid synthetic peptide near the center of human NKX2-8. Purification Method Affinity chromatography purified via peptide column. Clone / IgG Subtype Polyclonal antibody Species Reactivity Human, Mouse, Rat Specificity NKX2-8 antibody is predicted to not cross-react with other NK2 homeobox family members. Formulation Antibody is supplied in PBS containing 0.02% sodium azide. Reconstitution During shipment, small volumes of antibody will occasionally become entrapped in the seal of the product vial. For products with volumes of 200 μl or less, we recommend gently tapping the vial on a hard surface or briefly centrifuging the vial in a tabletop centrifuge to dislodge any liquid in the container’s cap. Storage & Stability Antibody can be stored at 4ºC for three months and at -20°C for up to one year. -

Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis Reveals Molecular Subtypes of Pancreatic Cancer

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, 2017, Vol. 8, (No. 17), pp: 28990-29012 Research Paper Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis reveals molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer Nitish Kumar Mishra1 and Chittibabu Guda1,2,3,4 1Department of Genetics, Cell Biology and Anatomy, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 68198, USA 2Bioinformatics and Systems Biology Core, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 68198, USA 3Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 68198, USA 4Fred and Pamela Buffet Cancer Center, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 68198, USA Correspondence to: Chittibabu Guda, email: [email protected] Keywords: TCGA, pancreatic cancer, differential methylation, integrative analysis, molecular subtypes Received: October 20, 2016 Accepted: February 12, 2017 Published: March 07, 2017 Copyright: Mishra et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Pancreatic cancer (PC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States with a five-year patient survival rate of only 6%. Early detection and treatment of this disease is hampered due to lack of reliable diagnostic and prognostic markers. Recent studies have shown that dynamic changes in the global DNA methylation and gene expression patterns play key roles in the PC development; hence, provide valuable insights for better understanding the initiation and progression of PC. In the current study, we used DNA methylation, gene expression, copy number, mutational and clinical data from pancreatic patients. -

Modeling the Human Segmentation Clock with Pluripotent Stem Cells 2 3 Mitsuhiro Matsuda1,10, Yoshihiro Yamanaka2,10, Maya Uemura2,3, Mitsujiro Osawa4, 4 Megumu K

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/562447; this version posted February 27, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Modeling the Human Segmentation Clock with Pluripotent Stem Cells 2 3 Mitsuhiro Matsuda1,10, Yoshihiro Yamanaka2,10, Maya Uemura2,3, Mitsujiro Osawa4, 4 Megumu K. Saito4, Ayako Nagahashi4, Megumi Nishio3, Long Guo5, Shiro Ikegawa5, 5 Satoko Sakurai6, Shunsuke Kihara7, Michiko Nakamura6, Tomoko Matsumoto6, Hiroyuki 6 Yoshitomi2,3, Makoto Ikeya6, Takuya Yamamoto6,8, Knut Woltjen6,9, Miki Ebisuya1*, 7 Junya Toguchida2,3, Cantas Alev2* 8 9 1 Laboratory for Reconstitutive Developmental Biology, RIKEN Center for Biosystems 10 Dynamics Research (RIKEN BDR), Kobe 650-0047, Japan. 11 2 Department of Cell Growth and Differentiation, Center for iPS Cell Research and 12 Application (CiRA), Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan. 13 3 Department of Regeneration Science and Engineering, Institute for Frontier Life and 14 Medical Sciences, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan. 15 4 Department of Clinical Application, Center for iPS Cell Research and Application 16 (CiRA), Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan. 17 5 Laboratory for Bone and Joint Diseases, RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical 18 Sciences (RIKEN IMS), Tokyo 108-8639, Japan. 19 6 Department of Life Science Frontiers, Center for iPS Cell Research and Application 20 (CiRA), Kyoto University, 606-8507, Kyoto 108-8639, Japan. 21 7 Department of Fundamental Cell Technology, Center for iPS Cell Research and 22 Application (CiRA), Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan. 23 8 AMED-CREST, AMED 1-7-1 Otemachi, Chiyodaku, Tokyo 100-004, Japan.