Ebworth House Painswick Gloucestershire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheepscombe Sheepscombe Jacks Green, Sheepscombe, Gloucestershire, GL6 7RA £599,950 Freehold

Sheepscombe Sheepscombe Jacks Green, Sheepscombe, Gloucestershire, GL6 7RA £599,950 Freehold An individual 4 bedroom detached family house set in this delightful elevated position with large garden and paddock. • DETACHED FAMILY HOUSE WITH EQUESTRIAN FACILITIES • entrance hall • kitchen/breakfast/family room • first floor sitting room • home office • 4 bedrooms • 3 bath/shower rooms • living room with second kitchen area • garage & driveway • large garden • c. 0.42 acre paddock • option to acquire an additional c. 2 acre paddock • oil central heating Description Beechcroft is a substantial property which is believed to date back to 1900. The house offers deceptively spacious, versatile family accommodation arranged over 2 floors and enjoys views of the picturesque countryside. The accommodation includes entrance hall, a lovely kitchen/breakfast/family room with fully retractable bi folding doors, first floor sitting room with feature wood burner and double doors to the sun terrace, home office, 4 bedrooms and 3 bath/shower rooms, 2 of which are en suite. There is also a living room with second kitchen area, currently arranged as self contained accommodation by way of incorporating one of the bedrooms and en suite facilities. Outside at the front is a driveway and garage. To the side and rear is the garden and paddock with stable block totalling approx. 0.62 of an acre. In addition there is the opportunity to acquire a further c. 2 acre paddock by way of separate negotiation. This paddock is located a short distance away. Situation Set in the heart of this charming Cotswold village surrounded by National Trust land and in a conservation area amidst steep wooded hills. -

Conserving the Painswick Valley's Rare Butterflies Project Update June 2013

CONSERVING THE PAINSWICK VALLEY’S RARE BUTTERFLIES PROJECT UPDATE JUNE 2013 Project Summary Conserving the Painswick Valley’s rare butterflies aims to restore and maintain the limestone grassland areas to help re-establish functioning metapopulations of both Large Blue and Duke of Burgundy butterflies involving 11 sites. The project will address the major conservation challenge of managing habitat for two species at opposite ends of the successional spectrum of habitat in the same landscape. The project secured 18 months funding from the BIFFA Trust and started in October 2012. The management and grazing on the project sites will be carefully targeted using the results of habitat assess- ments, Large Blue and Duke of Burgundy monitoring and Ant surveys. Each site manager and or owner receives detailed advice on where to target the scrub management with a tailored grazing regime according to the live- stock used by their grazier. Project Achievements The volunteer element of the project has continued since October 2012. Work delivered through contractors commenced in January 2013 with some weed control planned for summer 2013. The following is a summary of what the project has achieved so far: Conservation days • An amazing total of 39 volunteer days involving scrub management and clearance over nine sites • Involved 363 individuals who have worked approximately 1568 hours in total Volunteer groups involved in the above include; Butterfly Conservation Gloucestershire Branch volunteers, Cirencester College Students, Cotswolds Wardens volunteers, Cranham Common volunteers (mainly residents) , Gloucestershire Probation Trust cli- ents, Gloucestershire Vale Conservation Volunteers. Hartpury College students, Local residents and volunteers as well as a local mountain bike group, Painswick volunteer group and Stroud Valleys Project volunteers. -

KINGSWOOD Village Design Statement Supplementary Information

KINGSWOOD Village Design Statement Supplementary Information 1 Contents Appendix 1 Community Assets and Facilities Appendix 2 Table of Organisations and Facilities within Kingswood Appendix 3 Fatal and Serious Accidents Kingswood Appendix 4 Fatal and serious Accidents Kingswood and Wotton-under-Edge Appendix 5 Wotton Road Charfield, August 2013 Appendix 6 Hillesley Road, Kingswood,Traffic Survey, September 2012 Appendix 7 Wickwar Road Traffic Survey Appendix 8 Kingswood Parish Council Parish Plan 2010 Appendix 9 List of Footpaths Appendix 10 Agricultural Land Classification Report June 2014 Appendix 11 Kingswood Playing Field Interpretation Report on Ground Investigation Appendix 12 Peer Review of Flood Risk Assessment Appendix 13 Kingswood Natural Environment Character Assessment Appendix 14 Village Design Statement Key Dates 2 Appendix 1 Community Assets and Facilities 3 Community Assets and Facilities Asset Use Location Ownership St Mary’s Church Worship High Street Church and Churchyard Closed Churchyard maintained by Kingswood parish Council The St Mary’s Room Community High Street Church Congregational Chapel Worship Congregational Chapel Kingswood Primary School Education Abbey Street Local Education Authority Lower School Room Education/ Worship Chapel Abbey Gateway Heritage Abbey Street English Heritage Dinneywicks Pub Recreation The Chipping Brewery B&F Gym and Coffee shop Sport and Recreation The Chipping Limited Company Spar Shop/Post Office Retail The Chipping Hairdressers Retail Wickwar Road All Types Roofing Retail High -

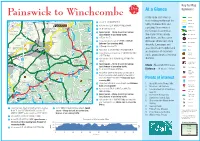

Painswick to Winchcombe Cycle Route

Great Comberton A4184 Elmley Castle B4035 Netherton B4632 B4081 Hinton on the Green Kersoe A38 CHIPPING CAMPDEN A46(T) Aston Somerville Uckinghall Broadway Ashton under Hill Kemerton A438 (T) M50 B4081 Wormington B4479 Laverton B4080 Beckford Blockley Ashchurch B4078 for Tewkesbury Bushley B4079 Great Washbourne Stanton A38 A38 Key to Map A417 TEWKESBURY A438 Alderton Snowshill Day A438 Bourton-on-the-Hill Symbols: B4079 A44 At a Glance M5 Teddington B4632 4 Stanway M50 B4208 Dymock Painswick to WinchcombeA424 Linkend Oxenton Didbrook A435 PH A hilly route from start to A Road Dixton Gretton Cutsdean Hailes B Road Kempley Deerhurst PH finish taking you through the Corse Ford 6 At fork TL SP BRIMPSFIELD. B4213 B4211 B4213 PH Gotherington Minor Road Tredington WINCHCOMBE Farmcote rolling Cotswold hills and Tirley PH 7 At T junctionB4077 TL SP BIRDLIP/CHELTENHAM. Botloe’s Green Apperley 6 7 8 9 10 Condicote Motorway Bishop’s Cleeve PH Several capturing the essence of Temple8 GuitingTR SP CIRENCESTER. Hardwicke 22 Lower Apperley Built-up Area Upleadon Haseld Coombe Hill the Cotswold countryside. Kineton9 Speed aware – Steep descent on narrow B4221 River Severn Orchard Nook PH Roundabouts A417 Gorsley A417 21 lane. Beware of oncoming traffic. The route follows mainly Newent A436 Kilcot A4091 Southam Barton Hartpury Ashleworth Boddington 10 At T junction TL. Lower Swell quiet lanes, and has some Railway Stations B4224 PH Guiting Power PH Charlton Abbots PH11 Cross over A 435 road SP UPPER COBERLEY. strenuous climbs and steep B4216 Prestbury Railway Lines Highleadon Extreme Care crossing A435. Aston Crews Staverton Hawling PH Upper Slaughter descents. -

Police and Crime Commissioner Election Number of Seats Division

Election of Police and Crime Commission for PCC Local Area Police and Crime Commissioner Election Number of Seats Gloucestershire Police Area 1 Election of County Councillors to Gloucestershire County Council Division Number of Division Number of Seats Seats Bisley & Painswick 1 Nailsworth 1 Cam Valley 1 Rodborough 1 Dursley 1 Stroud Central 1 Hardwicke & Severn 1 Stonehouse 1 Minchinhampton 1 Wotton-under-Edge 1 TOTAL 10 Election of District Councillors to Stroud District Council District Council Number of District Council Election Seats Election Amberley & Woodchester 1 Randwick, Whiteshill & 1 Ruscombe Berkeley Vale 3 Rodborough 2 Bisley 1 Severn 2 Cainscross 3 Stonehouse 3 Cam East 2 Stroud Central 1 Cam West 2 Stroud Farmhill & Paganhill 1 Chalford 3 Stroud Slade 1 Coaley & Uley 1 Stroud Trinity 1 Dursley 3 Stroud Uplands 1 Hardwicke 3 Stroud Valley 1 Kingswood 1 The Stanley 2 Minchinhampton 2 Thrupp 1 Nailsworth 3 Wotton-under-Edge 3 Painswick & Upton 3 TOTAL 51 Election of Parish/Town Councillors to [name of Parish/Town] Council. Parish/Town Number of Parish/Town Number of Council/Ward Seats Council/Ward seats Minchinhampton (Amberley Alkington 7 Ward) 2 Minchinhampton (Box Arlingham 7 Ward) 1 Minchinhampton Berkeley 9 (Brimscombe Ward) 3 Minchinhampton (North Bisley (Bisley Ward) 4 Ward) 6 Minchinhampton (South Bisley (Eastcombe Ward) 4 Ward) 3 Bisley (Oakridge Ward) 4 Miserden 5 Brookthorpe-with-Whaddon 6 Moreton Valence 5 Cainscross (Cainscross Ward) 2 Nailsworth 11 Cainscross (Cashes Green East Ward) 3 North Nibley 7 Cainscross -

Beacon Directory 2018

Directory 2018 published by The Painswick Beacon sections about 400 entries ACCOMMODATION BANKING index BUILDING and DECORATING BUSINESSES and SHOPS on pages CAMPING and CARAVANS 32 - 34 CHARITIES CHURCHES and CHURCH ORGANISATIONS CLUBS and SOCIETlES including sport addresses EDUCATION and EMERGENCIES and UTILITIES telephone ENTERTAINMENT numbers ESTATE AGENTS are for FARMERS, BREEDERS and LANDHOLDERS Painswick INFORMATION SERVICES and KENNELS 01452 LIBRARY SERVICES unless stated MEDICAL, HEALTH and THERAPY SERVICES MEETING HALLS PUBLIC TRANSPORT RESTAURANTS and PUBS STATUTORY AUTHORITIES and REPRESENTATIVES TAXIS and CHAUFFEUR SERVICES maps PAINSWICK VILLAGE and CENTRAL AREA This Directory is available on-line at www.painswickbeacon.org.uk Contact points for the Beacon are: • Berry Cottage, Paradise, Painswick, GL6 6TN • The Beacon post box, adjacent to the public telephone in New Street • E-mail to [email protected] * Directory entries: email to [email protected] or hard copy in the Beacon post box 2 ACCOMMODATION Court House Manor ACCOMMODATION Hale Lane GL6 6QE 814849 Luxury B&B, exclusive house hire and Falcon Inn weddings,13 rooms, private car park New Street GL6 6UN info&courthousemanor.co.uk 814222 www.courthousemanor.co.uk Restaurant, bars, function room for hire. 11 en-suite bedrooms. Damsells Lodge Large car park. Open all year. The Park, Painswick GL6 6SR [email protected] 813777 www.falconpainswick.co.uk B&B 1do. 1fam. 1tw. all en suite The Painswick Washwell Farm Kemps Lane GL6 6YB Cheltenham Road GL6 6SJ 813688 813067 or 07866916242 16 bedrooms, 2 spa treatment rooms, B&B 1do. en suite restaurant, private dining room. On-site car park. -

Walk Westward Now Along This High Ridge and from This Vantage Point, You Can Often Gaze Down Upon Kestrels Who in Turn Are Scouring the Grass for Prey

This e-book has been laid out so that each walk starts on a left hand-page, to make print- ing the individual walks easier. When viewing on-screen, clicking on a walk below will take you to that walk in the book (pity it can’t take you straight to the start point of the walk itself!) As always, I’d be pleased to hear of any errors in the text or changes to the walks themselves. Happy walking! Walk Page Walks of up to 6 miles 1 East Bristol – Pucklechurch 3 2 North Bristol – The Tortworth Chestnut 5 3 North Bristol – Wetmoor Wood 7 4 West Bristol – Prior’s Wood 9 5 West Bristol – Abbots Leigh 11 6 The Mendips – Charterhouse 13 7 East Bristol – Willsbridge & The Dramway 16 8 Vale of Berkeley – Ham & Stone 19 Walks of 6–8 miles 9 South Bristol – Pensford & Stanton Drew 22 10 Vale of Gloucester – Deerhurst & The Severn Way 25 11 Glamorgan – Castell Coch 28 12 Clevedon – Tickenham Moor 31 13 The Mendips – Ebbor Gorge 33 14 Herefordshire – The Cat’s Back 36 15 The Wye Valley – St. Briavels 38 Walks of 8–10 miles 16 North Somerset – Kewstoke & Woodspring Priory 41 17 Chippenham – Maud Heath’s Causeway 44 18 The Cotswolds – Ozleworth Bottom 47 19 East Mendips – East Somerset Railway 50 20 Forest of Dean – The Essence of the Forest 54 21 The Cotswolds – Chedworth 57 22 The Cotswolds – Westonbirt & The Arboretum 60 23 Bath – The Kennet & Avon Canal 63 24 The Cotswolds – The Thames & Severn Canal 66 25 East Mendips – Mells & Nunney 69 26 Limpley Stoke Valley – Bath to Bradford-on-Avon 73 Middle Hope (walk 16) Walks of over 10 miles 27 Avebury – -

Natural Advantage: Action for Biodiversity in the South West

Natural Advantage: Action for Biodiversity in the South West Case Studies in Sustainability • NATURAL ADVANTAGE:Action for Biodiversity in the South West • NATURAL ADVANTAGE:Action for Biodiversity in the South West Nature for all The nature conservation resource in our region is a major asset which we should all be proud of. Our characteristic and remarkable combination of wildlife and geological heritage is significant as an attraction to tourists, for businesses seeking to relocate, and as a major contributor to the quality of life in the South West. This has been highlighted in the recently published Regional Environment Strategy. None of us can fail to appreciate this wonderful heritage but it has been harder to understand what action is needed to care for it. This booklet clearly demonstrates the breadth of what is being done now. Across the region a host of organisations and individuals are working in partnership to maintain and enhance this precious nature conservation heritage. Wildlife and habitats are benefiting, but as these case studies demonstrate the benefits also extend across to economic and social well being. What is important is that these studies act to promote further action in the South West.To ensure that we pass on to future generations a wealth of wildlife and habitats, that continue to enhance the quality of life of all those who live, work or visit here. The SW Regional Biodiversity Partnership must be congratulated for putting together this important “ When we see land as a booklet. It is a celebration of what we can all achieve when we work in partnership. -

South West West

SouthSouth West West Berwick-upon-Tweed Lindisfarne Castle Giant’s Causeway Carrick-a-Rede Cragside Downhill Coleraine Demesne and Hezlett House Morpeth Wallington LONDONDERRY Blyth Seaton Delaval Hall Whitley Bay Tynemouth Newcastle Upon Tyne M2 Souter Lighthouse Jarrow and The Leas Ballymena Cherryburn Gateshead Gray’s Printing Larne Gibside Sunderland Press Carlisle Consett Washington Old Hall Houghton le Spring M22 Patterson’s M6 Springhill Spade Mill Carrickfergus Durham M2 Newtownabbey Brandon Peterlee Wellbrook Cookstown Bangor Beetling Mill Wordsworth House Spennymoor Divis and the A1(M) Hartlepool BELFAST Black Mountain Newtownards Workington Bishop Auckland Mount Aira Force Appleby-in- Redcar and Ullswater Westmorland Stewart Stockton- Middlesbrough M1 Whitehaven on-Tees The Argory Strangford Ormesby Hall Craigavon Lough Darlington Ardress House Rowallane Sticklebarn and Whitby Castle Portadown Garden The Langdales Coole Castle Armagh Ward Wray Castle Florence Court Beatrix Potter Gallery M6 and Hawkshead Murlough Northallerton Crom Steam Yacht Gondola Hill Top Kendal Hawes Rievaulx Scarborough Sizergh Terrace Newry Nunnington Hall Ulverston Ripon Barrow-in-Furness Bridlington Fountains Abbey A1(M) Morecambe Lancaster Knaresborough Beningbrough Hall M6 Harrogate York Skipton Treasurer’s House Fleetwood Ilkley Middlethorpe Hall Keighley Yeadon Tadcaster Clitheroe Colne Beverley East Riddlesden Hall Shipley Blackpool Gawthorpe Hall Nelson Leeds Garforth M55 Selby Preston Burnley M621 Kingston Upon Hull M65 Accrington Bradford M62 -

Brian Knight

STRATEGY, MISSION AND PEOPLE IN A RURAL DIOCESE A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF THE DIOCESE OF GLOUCESTER 1863-1923 BRIAN KNIGHT A thesis submitted to the University of Gloucestershire in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities August, 2002 11 Strategy, Mission and People in a Rural Diocese A critical examination of the Diocese of Gloucester 1863-1923 Abstract A study of the relationship between the people of Gloucestershire and the Church of England diocese of Gloucester under two bishops, Charles John Ellicott and Edgar Charles Sumner Gibson who presided over a mainly rural diocese, predominantly of small parishes with populations under 2,000. Drawing largely on reports and statistics from individual parishes, the study recalls an era in which the class structure was a dominant factor. The framework of the diocese, with its small villages, many of them presided over by a squire, helped to perpetuate a quasi-feudal system which made sharp distinctions between leaders and led. It is shown how for most of this period Church leaders deliberately chose to ally themselves with the power and influence of the wealthy and cultured levels of society and ostensibly to further their interests. The consequence was that they failed to understand and alienated a large proportion of the lower orders, who were effectively excluded from any involvement in the Church's affairs. Both bishops over-estimated the influence of the Church on the general population but with the twentieth century came the realisation that the working man and women of all classes had qualities which could be adapted to the Church's service and a wider lay involvement was strongly encouraged. -

A Guide to the Wonderful Walks

A guide to the wond erful walks Friday 5th May - Sunda y 7th May Welcome to the launch of the Tourist Information in Wotton (including rail and bus information): • One Stop Shop, Civic Centre, GL12 7DN (01453) 521659 Wotton Walking Festival [email protected] • Heritage Centre, The Chipping GL12 7AD (01453) 521541 We are looking forward to showing off our town and the surrounding countryside Directions when travelling by car during the three days of the festival and also hope that we can encourage many From M5, Junction 14 Take B4059 (signposted Wotton-under-Edge), turning left at T junction on to more people to get out walking – it is so good for our physical and mental wellbeing! B4058. Continue through Charfield, this road will bring you into Wotton-under- Edge. If you are local you may discover walks that you have not been on before, and if you are new to the area – a very special welcome to you. From M4, Junction 18 (Bath/Stroud A46) Leave Motorway at Tormarton Interchange (signposted Stroud/Bath A46), and Wotton is a charming country town, steeped in history, nestled in the southern at roundabout take 2nd exit (signposted Stroud A46). At Petty France, turn left Cotswold Hills, equidistant from Gloucester and Bristol, Cheltenham, Cirencester (signposted Hawkesbury Upton/Hillesley). Follow local signs to Wotton-under- and Bath. Wotton forms part of the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Edge. and the Cotswold Way National Trail runs through the town. Trust in You CIC have been meeting with some town councillors and a group Where to park Chipping Car Park GL12 7AD of enthusiastic and knowledgeable voluntary walk leaders to plan a series of 12 36 short-stay spaces (maximum stay 3 hours between 8.00am-6.00pm) and walks to take place over the 3 days of the festival. -

Conservation Management Plans Relating to Historic Designed Landscapes, September 2016

Conservation Management Plans relating to Historic Designed Landscapes, September 2016 Site name Site location County Country Historic Author Date Title Status Commissioned by Purpose Reference England Register Grade Abberley Hall Worcestershire England II Askew Nelson 2013, May Abberley Hall Parkland Plan Final Higher Level Stewardship (Awaiting details) Abbey Gardens and Bury St Edmunds Suffolk England II St Edmundsbury 2009, Abbey Gardens St Edmundsbury BC Ongoing maintenance Available on the St Edmundsbury Borough Council Precincts Borough Council December Management Plan website: http://www.stedmundsbury.gov.uk/leisure- and-tourism/parks/abbey-gardens/ Abbey Park, Leicester Leicester Leicestershire England II Historic Land 1996 Abbey Park Landscape Leicester CC (Awaiting details) Management Management Plan Abbotsbury Dorset England I Poore, Andy 1996 Abbotsbury Heritage Inheritance tax exempt estate management plan Natural England, Management Plan [email protected] (SWS HMRC - Shared Workspace Restricted Access (scan/pdf) Abbotsford Estate, Melrose Fife Scotland On Peter McGowan 2010 Scottish Borders Council Available as pdf from Peter McGowan Associates Melrose Inventor Associates y of Gardens and Designed Scott’s Paths – Sir Walter Landscap Scott’s Abbotsford Estate, es in strategy for assess and Scotland interpretation Aberdare Park Rhondda Cynon Taff Wales (Awaiting details) 1997 Restoration Plan (Awaiting Rhondda Cynon Taff CBorough Council (Awaiting details) details) Aberdare Park Rhondda Cynon Taff