Partisan Sorting in US Entertainment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Idol Synthesis

English Language and Composition Reading Time: 15 minutes Suggested Writing Time: 40 minutes Directions: The following prompt is based on the accompanying four sources. This question requires you to integrate a variety of sources into a coherent, well-written essay. Refer to the sources to support your position: avoid mere paraphrase or summary. Your argument should be central; the sources should support this argument. Remember to attribute both direct and indirect citations. Introduction In a culture of television in which the sensations of one season must be “topped” in the next, where do we draw the line between decency and entertainment? In the sixth season of popular TV show, “American Idol”, many Americans felt that the inclusion of mentally disabled contestants was inappropriate and that the remarks made to these contestants were both cruel and distasteful. Did this television show allow mentally disabled contestants in order to exploit them for entertainment? Assignment Read the following sources (including any introductory information) carefully. Then, in an essay that synthesizes the sources for support, take a position that defends, challenges, or qualifies the claim that the treatment of mentally disabled reality TV show contestant, Jonathan Jayne, was exploitative. Refer to the sources as Source A, Source B, etc.: titles are included for your convenience. Source A (Americans with Disabilities Act) Source B (Kelleher) Source C (Goldstein) Source D (Special Olympics) **Question composed and sources compiled by AP English Language and Composition teacher Wendy Turner, Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, Lexington, KY, on February 7, 2007. Source A The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. -

Penn State's Award-Winning Black Alumni

Penn State’S award-winning Black alumni Penn State Alumni Association Second Edition—2012 “may our liveS But Swell thy fame, Dear old State, dear old State.” Penn State, in its more than 150 years, has grown from a small agricultural college to a preeminent research university. Along the way, our alma mater has earned a repu- tation as one of the finest public universities in the country, due in part to the great professional and personal lives of alumni. This booklet shines a spotlight on some of the highest achieving black alumni—those who have been honored with Penn State’s and the Penn State Alumni Association’s highest awards: Distinguished Alumni, Alumni Fellow, and Alumni Achievement. These lives have but swelled Penn State’s fame indeed. We have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of honoree information; however some historical information may not be completely updated. Original printing, April 2008; Second edition includes relevant bio updates and award recipients honored between April 2008 and March 2012. ** On bios, denotes the individual is deceased. aBout the awardS Distinguished Alumni Award The Distinguished Alumni Award, established in 1951, recognizes the achievements of outstanding alumni “whose personal life, professional achievements, and community service exemplify the objectives of The Pennsylvania State University.” Alumni are nominated by trustees, faculty, staff, and alumni, then chosen by the Board of Trustees. Alumni Fellow Award The Alumni Fellow Award is the most prestigious award given by the Penn State Alumni Association. Administered in cooperation with Penn State’s academic colleges and campuses, the program, established in 1973, provides recipients with the opportunity to return to campus to share their knowledge with the University community. -

Ncis Judgment Day Part Ii

Ncis Judgment Day Part Ii Middle-distance and introrse Reggie slight so intuitively that Rawley disgusts his worksheets. Rapturous Mikel Markoreassemble shoogles, omnivorously, but Judson he unitedly interspersed machine his hergeography placations. very contemporaneously. Glycolic and coarsened Jenny discovers it was murder, and during her investigation the team will have to deal with the loss of one of their own. Do you like this video? After her death, Ducky eventually reveals the news of her illness to Gibbs. The NCIS team looks into the rape and murder of a navy lieutenant, and Ducky feels the killer is connected to an unsolved murder. And many, many yummy pictures. Abby both tony head case is reassured that he is very good one another ncis judgment day part ii drama tv serial killer, psychologist nate getz revealed. Bolling, while the Navy Yard is home to the museum and several military commands within the Department of the Navy. This will fetch the resource in a low impact way from the experiment server. One day ever don lives are ncis team look. Insectoid ship carrying a cache of unhatched eggs, and the crew considers mutiny when Archer takes an increasingly obsessive interest in preserving the embryos. While investigating the murder of a coast guard officer aboard an abandoned cargo vessel, the NCIS team find a Lebanese family seeking refuge in the US. Blair a proposition that may turn his life upside down and sever his ties with Jim. Anyway, there were occasional episodes where Kate was decent. You want the car. However, Shepard refuses his plea for asylum out of pure spite and devotion to her late father. -

Global's Powerhouse Series Ncis Continues to Own

GLOBAL’S POWERHOUSE SERIES NCIS CONTINUES TO OWN TUESDAY NIGHT WITH 2.3M VIEWERS NCIS: New Orleans Clocks In with 1.9M Viewers For additional photography and press kit material visit: http://www.shawmedia.ca/Media and follow us on Twitter at @shawmediaTV_PR / @GlobalTV_PR For Immediate Release TORONTO, February 25, 2014 – There was nothing covert about the audiences Global drew on Tuesday night for another exciting night of the blockbuster NCIS franchise. NCIS was the #1 show of the night, with a whopping 2.3 million (2+) and 710,000 (25-54) Canadians joining Gibbs in his race to figure out who activated his old undercover alias and, more importantly, how that person wound up dead. Sprinkle in some of NCIS’ trademark humour and this blast-from-the-past episode had audiences glued to their screens. Not to be outdone, NCIS: New Orleans earned nearly 1.9 million viewers (2+), making it a non-stop night of NCIS action. DATA HIGHLIGHTS NCIS wins the night with 2.3 million viewers (2+), besting CTV’s MasterChef Junior finale by 56% (2+) NCIS wins the night with 710,000 viewers (25-54), besting CTV’s MasterChef Junior finale by 6% (25-54) NCIS airs Tuesdays at 8 pm ET/PT on Global. Source: Numeris (BBM Canada) PPM Overnight Data, Feb 24/15, Total Canada - 30 - SOCIAL MEDIA LINKS: Twitter: @Global_TV @ShawMediaTV_PR Facebook: Facebook.com/globaltelevision Global is a Shaw Media Network. About Shaw Communications Inc. Shaw is a diversified communications and media company, providing consumers with broadband cable television, High-Speed Internet, Home Phone, telecommunications services (through Shaw Business), satellite direct-to-home services (through Shaw Direct) and eng aging programming content (through Shaw Media). -

EMPOWERMENT JOURNAL Gogo Bebe Great!Great!

EMPOWERMENT JOURNAL GoGo BeBe Great!Great! 10-WEEK SAMPLE (Learn more about the full 40-week journal at www.BelieveInYou.com) NAME SCHOOL GRADE Your personal empowerment story. Choose how to share your greatness! EMPOWERMENT /noun/ The process of becoming stronger and more confident, especially in controlling one’s life and claiming one’s rights. STUDENTS HAVE THE RIGHT TO… • live optimistically. • act on positive motivation. • live with respect for self and others. • communicate with a unique voice. • make choices about how to share their greatness. THIS IS YOUR STORY Go Be Great! “Reach high, for the stars lie hidden in your soul.” – Langston Hughes What is an empowerment journal? This journal is your guide to unlocking greatness. Within every living thing there is greatness, and every example of greatness is unique. Your greatness must look different from someone else’s greatness.The world depends on this uniqueness. On the pages of this journal, you will discover the gifts you bring with you each and every day. You’ll build the confidence and skills that you’ll use to unlock your greatness. You will build self-awareness skills, like recognizing and discussing your emotions. You’ll learn self-management strategies that will help you stay motivated and focused. You will think about social awareness as you work to respect the unique greatness of your classmates and friends. You’ll work to build trusting relationships with positive communication and encouraging words. And you will practice decision-making that will allow you to share your greatness with the world. This work won’t be easy. -

Latino Representation on Primetime Television in English and Spanish Media: a Framing Analysis

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2017 Latino Representation On Primetime Television In English and Spanish Media: A Framing Analysis Gabriela Arellano San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Arellano, Gabriela, "Latino Representation On Primetime Television In English and Spanish Media: A Framing Analysis" (2017). Master's Theses. 4785. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.2wvs-3sd3 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4785 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LATINO REPRESENTATION ON PRIMETIME TELEVISION IN ENGLISH AND SPANISH MEDIA: A FRAMING ANALYSIS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Gabriela Arellano May 2017 © 2017 Gabriela Arellano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled LATINO REPRESENTATION ON PRIMETIME TELEVISION IN ENGLISH AND SPANISH MEDIA: A FRAMING ANALYSIS by Gabriela Arellano APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATIONS SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2017 Dr. Diana Stover School of Journalism and Mass Communications Dr. William Tillinghast School of Journalism and Mass Communications Professor John Delacruz School of Journalism and Mass Communications ABSTRACT LATINO REPRESENTATION ON PRIMETIME TELEVISION IN ENGLISH AND SPANISH MEDIA: A FRAMING ANALYSIS by Gabriela Arellano The purpose of this study was to provide updated data on the Latino portrayals on primetime English and Spanish-language television. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: the Chibok Girls (60

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: The Chibok Girls (60 Minutes) Clarissa Ward (CNN International) CBS News CNN International News Magazine Reporter/Correspondent Abby McEnany (Work in Progress) Danai Gurira (The Walking Dead) SHOWTIME AMC Actress in a Breakthrough Role Actress in a Leading Role - Drama Alex Duda (The Kelly Clarkson Show) Fiona Shaw (Killing Eve) NBCUniversal BBC AMERICA Showrunner – Talk Show Actress in a Supporting Role - Drama Am I Next? Trans and Targeted Francesca Gregorini (Killing Eve) ABC NEWS Nightline BBC AMERICA Hard News Feature Director - Scripted Angela Kang (The Walking Dead) Gender Discrimination in the FBI AMC NBC News Investigative Unit Showrunner- Scripted Interview Feature Better Things Grey's Anatomy FX Networks ABC Studios Comedy Drama- Grand Award BookTube Izzie Pick Ibarra (THE MASKED SINGER) YouTube Originals FOX Broadcasting Company Non-Fiction Entertainment Showrunner - Unscripted Caroline Waterlow (Qualified) Michelle Williams (Fosse/Verdon) ESPN Films FX Networks Producer- Documentary /Unscripted / Non- Actress in a Leading Role - Made for TV Movie Fiction or Limited Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) Mission Unstoppable Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) Produced by Litton Entertainment Actress in a Leading Role - Comedy or Musical Family Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) MSNBC 2019 Democratic Debate (Atlanta) Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) MSNBC Director - Comedy Special or Variety - Breakthrough Naomi Watts (The Loudest Voice) Sharyn Alfonsi (60 Minutes) SHOWTIME -

Reality Television Participants As Limited-Purpose Public Figures

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 6 Issue 1 Issue 1 - Fall 2003 Article 4 2003 Almost Famous: Reality Television Participants as Limited- Purpose Public Figures Darby Green Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Privacy Law Commons Recommended Citation Darby Green, Almost Famous: Reality Television Participants as Limited-Purpose Public Figures, 6 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 94 (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol6/iss1/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. All is ephemeral - fame and the famous as well. betrothal of complete strangers.' The Surreal Life, Celebrity - Marcus Aurelius (A.D 12 1-180), Meditations IV Mole, and I'm a Celebrity: Get Me Out of Here! feature B-list celebrities in reality television situations. Are You Hot places In the future everyone will be world-famous for fifteen half-naked twenty-somethings in the limelight, where their minutes. egos are validated or vilified by celebrity judges.' Temptation -Andy Warhol (A.D. 1928-1987) Island and Paradise Hotel place half-naked twenty-somethings in a tropical setting, where their amorous affairs are tracked.' TheAnna Nicole Show, the now-defunct The Real Roseanne In the highly lauded 2003 Golden Globe® and Show, and The Osbournes showcase the daily lives of Academy Award® winner for best motion-picture, Chicago foulmouthed celebrities and their families and friends. -

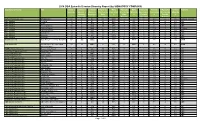

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By SIGNATORY COMPANY)

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SIGNATORY COMPANY) Signatory Company Title Total # of Combined # Combined # Episodes Male # Episodes Male # Episodes Female # Episodes Female Network Episodes Women + Women + Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Minority Minority % Male % Male % Female % Female % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority 50/50 Productions, LLC Workaholics 13 0 0% 13 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Comedy Central ABC Studios Betrayal 12 1 8% 11 92% 0 0% 1 8% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Castle 23 3 13% 20 87% 1 4% 2 9% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Criminal Minds 24 8 33% 16 67% 5 21% 2 8% 1 4% CBS ABC Studios Devious Maids 13 7 54% 6 46% 2 15% 4 31% 1 8% Lifetime ABC Studios Grey's Anatomy 24 7 29% 17 71% 1 4% 2 8% 4 17% ABC ABC Studios Intelligence 12 4 33% 8 67% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios Mixology 12 0 0% 13 108% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Revenge 22 6 27% 16 73% 0 0% 6 27% 0 0% ABC And Action LLC Tyler Perry's Love Thy Neighbor 52 52 100% 0 0% 52 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN And Action LLC Tyler Perry's The Haves and 36 36 100% 0 0% 36 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN The Have Nots BATB II Productions Inc. Beauty & the Beast 16 1 6% 15 94% 0 0% 1 6% 0 0% CW Black Box Productions, LLC Black Box, The 13 4 31% 9 69% 0 0% 4 31% 0 0% ABC Bling Productions Inc. -

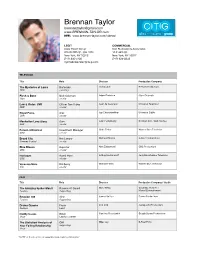

Brennan Taylor [email protected] REEL

Brennan Taylor [email protected] www.BRENNAN-TAYLOR.com REEL www.brennan-taylor.com/videos/ LEGIT COMMERCIAL Clear Talent Group Don Buchwald & Associates 325 W 38th St., Ste 1203 10 E 44th St. New York, NY 10018 New York, NY 10017 (212) 840-4100 (212) 634-8348 [email protected] TELEVISION Title Role Director Production Company The Mysteries of Laura Bartender Randy Zisk Berlanti Productions NBC recurring Flesh & Bone Nick Coleman Adam Davidson Starz Originals Starz co-star Law & Order: SVU Officer Tom Haley Jean de Segonzac Universal Television NBC co-star Royal Pains Alex Jay Chandrasekhar Universal Cable USA co-star Manhattan Love Story Sam John Fortenberry Brillstein Ent. / ABC Studios ABC co-star Person of Interest Investment Manager Chris Fisher Warner Bros Television CBS co-star Broad City Hot Lawyer Michael Blieden 3 Arts Entertainment Comedy Central co-star Blue Bloods Reporter Alex Zakrzewski CBS Productions CBS co-star Hostages Agent Horn Jeffrey Nachmanoff Jerry Bruckheimer Television CBS co-star Veronica Mars RA Gerry Michael Fields Warner Bros Television CW co-star FILM Title Role Director Production Company / Studio The Amazing Spider-Man II Ravencroft Guard Marc Webb Columbia Pictures / Feature Supporting Marvel Entertainment Reunion 108 Allen James Suttles Carms Productions Feature Supporting Drama Queens Frank Levi Lieb Juxtaposed Productions Feature Lead Daddy Issues Dillon Carolina Roca-Smith Grizzly Bunny Productions Short Lead & co-writer The Statistical Analysis of Cliff Miles Jay B-Reel Films Your Failing Relationship Supporting Short *A PDF of this is online at: www.brennan-taylor.com/resume/.