The Idealised Image of the Australian Home: a Myth in the Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Built Pedagogy Education Design Is a Specialised Field with Different

University of Melbourne New Building for the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning Expression of Interest Built Pedagogy Education design is a specialised field with different characteristics and benchmarks from other building types Paul Morgan Architects specializes in the design of university and TAFE buildings. A feature of the buildings is the idea of permeability: the activities of students and staff are revealed to passers-by. This animates the internal spaces and advertises the functions that occur within. It is about the ‘theatre’ of architecture, and can be seen in the Box Hill Institute Trade Facility and CGIT Learning Centre on this page. Advanced structural and servicing techniques are demonstrated in the proposed 6 Star Green Star Vicurban Chisholm project. Above top to bottom: VicUrban Chisholm, Completion TBC; CGIT Learning Centre, Leongatha, 2009; RMIT University, Hamilton, 2001 Above right top to bottom:Trades facility, Box Hill Institute of TAFE, 2006; CGIT Learning Centre, Warragul, 2007; Chisholm Institute Automotive and Logisitcs Centre, 2008 Far right: NMIT, Stage 1 Development, Epping, 2009 Right: Lecture Theatre, Victoria University of Technology, Werribee, 1997 PMA Education Clients Box Hill Institute Central Gippsland Institute of TAFE Chisholm Institute of TAFE Danang University Department of Education & Training Hue University Monash University Newman College Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE RMIT TAFE RMIT University RMIT International University Vietnam Victoria University of Technology www.paulmorganarchitects.com -

Decision About Registration of 12 Marawa Pl, Aranda) Notice 2008 (No 1

Australian Capital Territory Heritage (Decision about Registration of 12 Marawa Pl, Aranda) Notice 2008 (No 1) Notifiable Instrument NI 2008 – 421 made under the Heritage Act 2004 section 42 Notice of decision about registration 1. Revocation This instrument replaces NI2008 – 121 2. Name of instrument This instrument is the Heritage (Decision about Registration for 12 Marawa Pl, Aranda) Notice 2008 (No 1). 3. Registration details of the place Registration details of the place are at Attachment A: Register entry for 12 Marawa Pl, Aranda, 4. Reason for decision The ACT Heritage Council has decided that the 12 Marawa Pl, Aranda meets one or more of the heritage significance criteria at s 10 of the Heritage Act 2004. The register entry is at Attachment A. 5. Date of Registration 11 September 2008. The Secretary ACT Heritage Council GPO Box 158 CANBERRA ACT 2602 ………………….. Gerhard Zatschler Secretary ACT Heritage Council GPO Box 158, Canberra ACT 2602 11 September 2008 Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY HERITAGE REGISTER For the purposes of s. 33 of the Heritage Act 2004, an entry to the heritage register has been prepared by the ACT Heritage Council for the following place: • 12 Marawa Place Block 6, Section 31 ARANDA DATE OF REGISTRATION Notified: 11 September 2008 Notifiable Instrument: NI2008–421 Copies of the Register Entry are available for inspection at the ACT Heritage Unit. For further information please contact: The Secretary ACT Heritage Council GPO Box 158, Canberra, ACT 2601 Telephone: 132281 Facsimile: (02) 6207 2229 Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au IDENTIFICATION OF THE PLACE • 12 Marawa Place, Block 6, Section 31, Suburb of Aranda, ACT. -

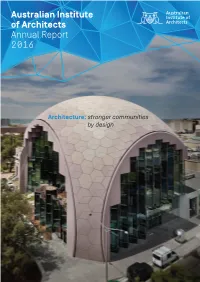

Australian Institute of Architects Annual Report 2016

Australian Institute of Architects Annual Report 2016 Architecture: stronger communities by design From the cover A City Transformed by Architectural Excellence Geelong City is emerging from difficult economic times unhelped by a poorly laid out 19th century civic centre. The award winning Geelong Library and Heritage Centre by ARM Architecture has revitalised the cultural precinct; providing function coupled to an iconic aesthetic. The design connects and enhances existing underutilised space providing multiple layers of value. This project clearly demonstrates how in this case, holistic design can transform the quaint concept of a ‘library’ into a vibrant and energised vertical village where the community can meet, collaborate, engage, learn and celebrate. The project’s pragmatic success is apparent in the record breaking visitor numbers that have exceeded all expectation. Geelong Library and Heritage Centre by ARM Architecture. Winner of the Sir Zelman Cowen Award for Public Architecture at the 2016 National Architecture Awards. Photographer: John Gollings 02 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS Contents Part One Introduction 04 National President's Report 06 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 08 Governance 10 Chapter Reports 12 Education 21 Advocacy 22 Membership 23 Awards and Prizes 24 Events and Conferences 26 Venice Biennale 28 Performance Indicators 30 All information contained in part one is correct as at 31 March 2017. Part Two – Financial Report Financial Summary 36 Financial Contents 38 AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS ANNUAL REPORT 2016 03 Building a strong voice for architecture Architecture has a powerful impact on our nation and as Following images represent: our cities and regions continue to grow, so too does the 1. -

John Wardle Architects

Vision Magazine 1 V ISION John Wardle Architects Fairhaven House Shearer’s Quarters Nigel Peck Centre Vision Magazine 2 CONTENTS The Material Man John Wardle leads a talented multi-disciplinary practice. The firm’s latest residence perches above Fairhaven Beach and is their second project to win the prestigious Robin Boyd Award. 04 3 Twitter Blog Bruny Island Shearer’s Quarters A return visit to a house that hasn’t sagged under the weight of huge acclaim. A precursor to the Fairhaven House and equally tuned to its remarkable setting. 26 Nigel Peck Centre Covered by Vision in 2008 and virtually ageless with its fusion of technology and art to create an inspirational education environment. 38 Contents Vision Magazine 4 THE MATERIAL MAN 5 THE MATERIAL MAN STRAW POLL ARCHITECTS TO DISCOVER WHO AMONG THEIR RANKS THEY MOST ADMIRE AND THE PRACTICE OF JOHN WARDLE CONSISTENTLY RATES. THIS MIGHT SURPRISE WARDLE, BUT NOT SHREWD OBSERVERS OF A FIRM THAT HAS BUILT SUCH AN OUTSTANDING BODY OF WORK. HE ENJOYS AN UNUSUALLY HIGH PEER REPUTATION - RARE IN A BUSINESS FRAUGHT WITH NARROW ESCAPES, FINANCIAL STRUGGLES AND GLOVES-OFF SPARRING. The Fairhaven House, Victoria Architect: John Wardle Architects Principal Glass Provider: Viridian Principal Glazing Resource: Viridian ThermoTechTM E Double Glazed Units incorporating SunergyTM Images & Text: Peter Hyatt & Jennifer Hyatt The Material Man Right A para-glider swoops past the house that occupies a high ridge-line. Vision Magazine 8 9 Left Design clarity and delicacy have helped win Wardle Sheltered, plaudits, not least among them his second Robin north-facing courtyard. Boyd Award. -

Survey-Of-Post-War-Built-Heritage-In-Victoria-Stage-1-Heritage-Alliance-2008 Part2.Pdf (PDF File

Identifier House Other name Milston House (former) 027-086 Address 6 Reeves Court Group 027 Residential Building (Private) KEW Category 472 House LGA City of Boroondara Date/s 1955-56 Designer/s Ernest Milston NO IMAGE AVAILABLE Theme 6.0 Building Towns, Cities & the Garden State Sub-theme 6.7 Making Homes for Victorians Keywords Architect’s Own Significance Architectural; aesthetic References This butterfly-roofed modernist house was designed by Ernest P Goad, Melbourne Architecture, p 171 Milton, noted Czech-born émigré architect, for his own use. Existing Listings AHC National Trust Local HO schedule Local Heritage Study Identifier House Other name 027-087 Address 54 Maraboor Street Group 027 Residential Building (Private) LAKE BOGA Category 472 House LGA Rural City of Swan Hill Date/s c.1955? Designer/s Theme 6.0 Building Towns, Cities & the Garden State Sub-theme 6.7 Making Homes for Victorians Keywords Image: Simon Reeves, 2002 Significance Aesthetic References Probably a rare survivor of the 1950s fad for decorating John Belot, Our Glorious Home (1978) houses, gardens and fences with shells and ceramic shards. This “Domestic Featurism” was documented by John Belot in the 1970s, but few examples would now remain intact. The famous “shell houses” of Arthur Pickford at Ballarat and Albert Robertson at Phillip Island are both no longer extant. Existing Listings AHC National Trust Local HO schedule Local Heritage Study heritage ALLIANCE 146 Job 2008-07 Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria Identifier House Other name Reeve House (former) 027-088 Address 21a Green Gully Road Group 027 Residential Building (Private) KEILOR Category 472 House LGA City of Brimbank Date/s 1955-60 Designer/s Fritz Janeba NO IMAGE AVAILABLE Theme 6.0 Building Towns, Cities & the Garden State Sub-theme 6.7 Making Homes for Victorians Keywords Significance Architectural; References One of few known post-war commissions of this Austrian émigré, who was an influential teacher within Melbourne University’s School of Architecture. -

Expression of Interest

Expression of Interest Prepared for the University of Melbourne - New Building for the Faculty of Architecture Building and Planning by Architectus Architectus Melbourne Level 7, 250 Victoria Parade East Melbourne VIC 3002 Australia T +61 3 9429 5733 F +61 9 429 8480 [email protected] www.architectus.com.au 1.1 BUILT PEDAGOGY VISIBILITY “In 1994 when we were designing the Hammond residence which was in a remote location, we were advised we would need 22 solar panels to meet energy needs. Our clients could only afford two panels and so sold the majority of their appliances. The two panels proved more than enough + our clients had to buy new appliances to ‘use up’ the stored energy. The lesson is that an understanding of energy and operational requirements is necessary for all involved in creating built environments.” Lindsay Clare - Director Architectus By learning about the building’s operation through experience + monitoring as part of their studies all students can learn how a building works (passively, technically and socially), Year 1 about light and ventilation, Year 2 about water, Year 3 etc...... the building as a ‘learning laboratory’ - fostering engagement and ownership and presenting the opportunity to deliver an experiential landmark for the university and the community. University of the Sunshine Coast Chancellery - Concept Plan and covered ‘market place’ - with visual connections to central landscape and library beyond The purpose of the new building is to create an environment where people want to be, and where they want to learn - about designing, planning and making - within spaces that promote engagement, research exploration, collaboration, connection, testing and discovery. -

Capability Durbach Block Efgh Scape Atelier 10 Arup

Selected Project Awards: 2006 The Brickpit Ring: RAIA Lloyd Rees Civic Design Award(NSW), RAIA National Special Jury Award COMPETITION 2005 Holman House: RAIA Wilkinson Award for Housing IDEAS 2004 Commonwealth Place, Canberra: NSW AILA State Award for Landscape Architecture DISCOURSE NSW AILA Excellence Award for Design in Landscape C CREATIVITY House Spry: The National Robin Boyd Award, NSW RAIA Architecture Award STUDIO ‘CULTURE’ THRIVES ON ENERGY SPECULATION, MUTUAL DISCOURSE, 2003 Commonwealth Place, Canberra: RAIA ACT Urban Design Award, RAIA National Urban Design Award Selected Awards / Publications: A NEXUS ON CAMPUS, CONNECTING Planning Institute Australia, RAIA & Australian Institute of Landscape First Place: Envisioning Gateway Competition, Van Alen Institute. Project title “H2Gro” CRITIQUE EXPERIMENTATION AND NEW IDEAS Architects. Australian Award for Design Excellence: Honorable mention. Featured in Frame: The Great Indoors, May 2009: Dogmatic, New York TO THE UNIVERSITY + CITY BEYOND INTELLECT 1998 The Droga Apartment: The National RAIA Robin Boyd Award for Housing EFGH collaborates with Diller Scodio + Renfro on “YOUprison: Some thoughts on the limitation of space and freedom.” COLLABORATION RAIA Wilkinson Award for Housing (NSW) Torino, Italy STUDIO CULTURE 1997 Apartment Einfeld, Darling Point: RAIA Merit Award for Interior Architecture Featured in Domus, March 2008: Does the punishment t the crime?” NEXUS Selected Recent Publications: Featured in Bidoun, Arts and Culture in the Middle East, Fall 2007:“Democracy Building” -

The Royal Australian Institute of Architects

NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS WINNERS 1981 - 2018 AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARD WINNERS 1 of 76 2018 NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Optus Stadium (WA) The COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture HASSELL COX HKS COMMERCIAL ARCHITECTURE Barwon Water (VIC) The Harry Seidler Award for Commercial Architecture GHDWoodhead International House Sydney (NSW) National Award for Commercial Architecture Tzannes Australian Federal Police Forensics and Data Centre (ACT) National Commendation for Commercial Architecture HASSELL Barangaroo House (NSW) National Commendation for Commercial Architecture Collins and Turner EDUCATIONAL ARCHITECTURE New Academic Street, RMIT University (VIC) The Daryl Jackson Award for Educational Architecture Lyons with NMBW Architecture Studio, Harrison and White, MvS Architects and Maddison Architects Monash University Learning and Teaching Building (VIC) National Award for Educational Architecture John Wardle Architects Macquarie University Incubator (NSW) National Award for Educational Architecture Architectus Highgate Primary School New Teaching Building (WA) National Commendation for Educational Architecture iredale pedersen hook architects ENDURING ARCHITECTURE Townsville Courts of Law – Edmund Sheppard Building (QLD) National Award for Enduring Architecture Hall, Phillips & Wilson Architects Pty Ltd HERITAGE Joynton Avenue Creative Centre and Precinct (NSW) The Lachlan Macquarie Award for Heritage Peter Stutchbury Architecture in association with -

The Architecture Symposium, Sydney

Design Speaks The Architecture Symposium, Sydney Design Speaks. The Architecture Symposium, Sydney Giving voice to Australia's world- class architects Tuesday 24 September 2019 SUPPORTING PARTNER Image not found or type unknown 01 Design Speaks The Architecture Symposium, Sydney Details. Program. When Tuesday 24 September 2019 8.30 am Attendee arrival 8.30 am – 5.00 pm () 9.00 am ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY Where 9.10 am OPENING COMMENTS Art Gallery of New South Wales Curators Laura Harding, Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban The Domain, Art Gallery Road Projects, Sydney NSW 2000 and Adam Haddow, SJB 9.25 am URBAN CAMPUS Program Info Ninotschka Titchkosky, BVN (Kambri cultural precinct, Responsive urbanism: The Australian National University). Architecture Symposium, Sydney Nigel Bertram, NMBW (RMIT University precinct). presents a curated line-up of 10.00 am contemporary Australian architects URBAN ENSEMBLES whose projects make explicit and Victoria Reeves, Kennedy Nolan (Nightingale Village). lyrical contributions to the framing Penny Fuller, Silvester Fuller (Loftus Lane). of the public realm. These are projects where a more engaging and 10.35 am CIVIC CATALYSTS responsive civic conversation is Tai Ropiha, Chrofi (Maitland Riverlink). being staged. Discussion will be Rodney Eggleston, March Studio (Kingborough shaped by a number of themes, Community Hub). investigating approaches to elements from urban and landscape 11.10 am Morning tea design, large-scale city quarters and 11.40 am infrastructure, to the architectural AGGREGATE URBANISM definition of streets, parks and Jared Webb, Richards and Spence (Cornerstone Stores). arcades, down to the intimacy of the Kerstin Thompson, Kerstin Thompson Architects (Balfe city's finer grain. -

View Handbook

www.temc.org.au Conference Ha nd bo ok 1 Save money on the document she’s reading. Spend it on the course she’s studying. Cost savings. Business efficiencies. Environmental and sustainability benefits. Happier students. There could be a lot more in your documents than you think. And even quite small changes to the way you manage your documents could release those benefits. Find out more by visiting the Fuji Xerox Australia booth at the Tertiary Education Management Conference or visit www.thedocumenteffect.com.au or phone 13 14 12. Xerox and the sphere of connectivity design are trademarks or registered trademarks of Xerox Corporation in the U.S. and/or other countries. TEMC Advertisement_A4_V3.indd 1 12/07/11 10:30 am Contents WELCOME 4 ORGANISING COMMITTEE 5 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENTS 6 ASSOCIATION INFORMATION 7 CONFERENCE & GENERAL INFORMATION 9 GUEST SPEAKERS 13 LEADERS PANEL - THE WAVE POOL - HIGHER EDUCATION 2015 & 2020 19 SOCIAL PROGRAM 21 ASSOCIATION EVENTS 22 SPONSORS 24 EXHIBITORS 33 CONFERENCE ABSTRACTS 44 POSTER ABSTRACTS 78 3 Welcome Welcome to Queensland, the Gold Coast and to TEMC 2011. The conference theme Riding the Waves and the supporting themes: challenge, change, support, routine and serendipity encapsulate our glorious location and the higher education environment in which we work. TEMC is a joint venture of the Association for Tertiary Education Management (ATEM) and the Tertiary Education Facilities Management Association (TEFMA). The conference organising committee see TEMC as more than the sum of these contributing parts. The delivery of services in higher education requires linkages and collaboration across professions and organisational units. -

The Award for Sustainable Architecture

Arts 2015, 3, 34-48; doi:10.3390/arts4020034 OPEN ACCESS arts ISSN 2076-0752 www.mdpi.com/journal/arts Article Framing the Field: The Award for Sustainable Architecture Ceridwen Owen * and Jennifer Lorrimar-Shanks † School of Architecture and Design, University of Tasmania, Locked Bag 1-323 Launceston Tasmania 7250, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-3-6324-4479; Fax: +61-3-6324-4477. External Editor: Volker M. Welter Received: 30 June 2014 / Accepted: 18 March 2015 / Published: 8 April 2015 Abstract: In this paper, we explore the effect that the increasingly powerful discourse of sustainability is having on the field of architecture. The term “field” derives from Bourdieu’s conceptualization of fields as dynamic spaces of social relations tending towards transformation or conservation. While the overlapping fields of sustainability and architecture have historically been characterized by resistance, shifts in environmental discourse towards complexity and systems thinking and the inclusion of cultural, social, political and economic concerns within the broader mandate of sustainability signal a more synergistic ideological terrain. We use methods of narrative analysis to explore these shifts through the localized discourse of the award for sustainable architecture within the Australian context and offer a brief comparative analysis of the sustainable architecture awards discourse in Britain and North America. As arguably the most public elucidations of the profession’s ideology, architecture awards are a productive place in which to explore constructions of “sustainable architecture”. -

NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARD WINNERS 1 of 84

NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS WINNERS 1981 - 2020 AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARD WINNERS 1 of 84 2020 NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Carlton Learning Precinct COLA (VIC) The COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Law Architects The COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture - Bankwest Stadium (NSW) Commendation Populous COMMERCIAL ARCHITECTURE Phoenix Central Park (NSW) The Harry Seidler Award for Commercial Architecture Durbach Block Jaggers and John Wardle Architects Three Capes Track Lodges (TAS) National Commendation for Commercial Architecture Andrew Burns Architecture Daramu House (NSW) National Commendation for Commercial Architecture Tzannes 9 Cremorne St (VIC) National Commendation for Commercial Architecture Fieldwork EDUCATIONAL ARCHITECTURE Ian Potter Southbank Centre, University of Melbourne (VIC) The Daryl Jackson Award for Educational Architecture John Wardle Architects Curtin University Midland Campus (WA) National Award for Educational Architecture Lyons with Silver Thomas Hanley MLC School Senior Centre (NSW) National Award for Educational Architecture BVN Carlton Learning Precinct COLA (VIC) National Commendation for Educational Architecture Law Architects ENDURING ARCHITECTURE Palm Garden House (NSW) National Award for Enduring Architecture Richard Leplastrier HERITAGE Bozen’s Cottage (TAS) The Lachlan Macquarie Award for Heritage – Joint winner Taylor & Hinds Architects Hollow Tree House (TAS) The Lachlan Macquarie Award for Heritage – Joint winner