Evening Prayer: Rite Two Wednesday, May 27, 2020 Opening

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King Aethelbert of Kent

Æthelberht of Kent Æthelberht (also Æthelbert, Aethelberht, Aethelbert, or Ethelbert) (c. 560 – 24 February 616) was King of Kent from about 558 or 560 (the earlier date according to Sprott, the latter according to William of Malmesbury Book 1.9 ) until his death. The eighth-century monk Bede, in his Ecclesiastical History of the English Peo- ple, lists Aethelberht as the third king to hold imperium over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. In the late ninth cen- tury Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Æthelberht is referred to as a bretwalda, or “Britain-ruler”. He was the first English king to convert to Christianity. Æthelberht was the son of Eormenric, succeeding him as king, according to the Chronicle. He married Bertha, the Christian daughter of Charibert, king of the Franks, thus building an alliance with the most powerful state in con- temporary Western Europe; the marriage probably took place before Æthelberht came to the throne. The influ- ence of Bertha may have led to the decision by Pope Gre- gory I to send Augustine as a missionary from Rome. Au- gustine landed on the Isle of Thanet in east Kent in 597. Shortly thereafter, Æthelberht converted to Christianity, churches were established, and wider-scale conversion to Christianity began in the kingdom. Æthelberht provided The state of Anglo-Saxon England at the time Æthelberht came the new mission with land in Canterbury not only for what to the throne of Kent came to be known as Canterbury Cathedral but also for the eventual St Augustine’s Abbey. Æthelberht’s law for Kent, the earliest written code in ginning about 550, however, the British began to lose any Germanic language, instituted a complex system of ground once more, and within twenty-five years it appears fines. -

On the Coins Forming a Necklace, Found in S

ON THE COINS FORMING A NECKLACE, FOUND IN S. MARTIN'S CHURCH YARD, CANTERBURY. AND NOW IN THE MAYER MUSEUM AT LIVERPOOL. By the Rei'. Daniel Henry Haigh, F.S.A.* (Read 2?th November, 1879.) " rpHERE was a church," says Ven. Bseda, " near the city of 1 " Canterbury, towards the east, made of old in honour of " S. Martin, whilst as yel the Romans dwelt in Britain." S. Martin died A.D. 397, the Roman domination in Britain ceased in 409, and the Angles came in 428; but many of the courtiers of the emperor Maximus, with whom, as his temporal sovereign, S. Martin had had very intimate relations, must have survived him, and to their veneration for his sanctity probably it was owing that a church was built in his honour, during this interval, almost contemporaneously with the erection of the earliest chapel over his tomb at Tours. When ^Ethelberht, king of Kent, received in marriage Bertha, daughter of Chariberht, king of the Franks, it was on this con dition, " that she should have leave to keep inviolate the rites of "her faith and religion, with the bishop Liudhard, whom her " parents had given to her as the helper of her faith ;" and to this church of S. Martin the queen was wont to repair for the exercises of religion, naturally preferring a church which bore * Written by the Rev. Daniel Henry Haigh for Joseph Mayer, F.S.A., to be read at a meeting of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. Mr. Haigh died suddenly, May, 1879. -

Bertha of Kent

Bertha of Kent See also: Bertha of Val d'Or in pavements, runs from the Buttermarket to St Mar- tin’s church via Lady Wootton’s Green. Saint Bertha or Saint Aldeberge (539 – c. 612) was the • In 2006 bronze statues of Bertha and Ethelbert were queen of Kent whose influence led to the Christianization installed on Lady Wootton’s Green as part of the of Anglo-Saxon England. She was canonized as a saint Canterbury Commemoration Society’s “Ethelbert for her role in its establishment during that period of and Bertha” project.[9] English history. • There is a wooden statue of Bertha inside St Martin’s church.[7] 1 Life Bertha was a Frankish princess, the daughter of Charibert 3 References I and his wife Ingoberga, granddaughter of the reign- ing King Chlothar I and great-granddaughter of Clovis [1] Gregory of Tours (539-594), History of the Franks, Book I and Saint Clothide, the latter dying when Bertha was 4 at fordham.edu [1] 5 years old. Her father died in 567, her mother in in [2] Taylor, Martin. The Cradle of English Christianity 589. Bertha had been raised near Tours.[2] Her marriage to pagan King Æthelberht of Kent was conditioned on [3] Wace, Henry and Piercy, William C., “Bertha, wife of her being allowed to practice her religion.[3] She brought Ethelbert, king of Kent”, Dictionary of Christian Biogra- her chaplain, Liudhard, with her to England.[4] Bertha phy and Literature to the End of the sixth Century, Hen- restored a Christian church in Canterbury, which dated drickson Publishers, Inc., ISBN 1-56563-460-8 from Roman times, dedicating it to Saint Martin of Tours. -

Review of Saint Augustine and the Conversion of England, Edited by R

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Theology & Religious Studies 12-1-2000 Review of Saint Augustine and the Conversion of England, edited by R. Gameson Joseph F. Kelly John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/theo_rels-facpub Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, Joseph F., "Review of Saint Augustine and the Conversion of England, edited by R. Gameson" (2000). Theology & Religious Studies. 27. http://collected.jcu.edu/theo_rels-facpub/27 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology & Religious Studies by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 876 CHURCH HISTORY Ecclesiawith its concern for sacerdotal formation (Lizzi). The large number of letters from Augustine indicates that he often wrote of personal issues that he mentioned in order to sway his correspondents (Rebillard). As a rule the episcopal office in cities was in flux, not yet the urban power base that it would later become. The fourth and fifth centuries were a seminal period in the development of bishops' roles within city life. In the third century Paul of Samosata, bishop of Antioch, had been a rich, established Roman procurator when he became bishop. The council that deposed him worried about his christology, but the clearest information concerns his filling his role as bishop with the trappings and power of his Roman office. Disciples of Christ were not to act that way. Wealthy, well-connected men became candidates for bishoprics, occasion- ally almost shanghaied into office. -

Saints and Their Function in the Kingdom of Mercia, 650-850

SAINTS AND THEIR FUNCTION IN THE KINGDOM OF MERCIA, 650-850 By WILLIAM MICHAEL FRAZIER Bachelor of Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1995 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December, 1998 SAINTS AND THEIR FUNCTION IN THE KINGDOM OF MERCIA, 650-850 Thesis Approved: Dean ofthe Graduate College ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my advisor, Dr. J. Paul Bischoff, for his guidance throughout the creation ofthis thesis. Without his suggestions and criticisms, I would have never completed a work worth submitting. To Dr Bischoff I also owe thanks for giving me something I have rarely had in my life: a challenge. I would also like to thank my other commi.ttee members, Dr. Eldevik and Dr. Petrin, who gave me many valuable suggestions during the revision ofthe thesis. Any mistakes that remain after their help are without a doubt my own. I truly appreciate the support which the History department extended to me, especially the financial support ofthe Teaching Assistantship I was generously given. To the wonderful people of the interlibrary loan department lowe an enormous debt. I simply could not have completed this work without the many articles and books which they procured for me. I would also like to thank my parents, Ron and Nancy, for their constant support. Anything good that I achieve in this life is a reflection on them. They have made me who I am today. Finally, I would like to extend my greatest appreciation to my wife, Cindy, who has stayed supportive throughout what has seemed an eternity of research and writing. -

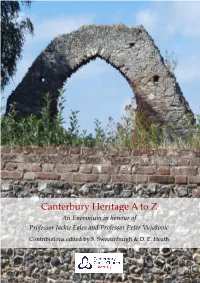

Canterbury's A

Canterbury Heritage A to Z An Encomium in honour of Professor Jackie Eales and Professor Peter Vujakovic Contributions edited by S. Sweetinburgh & D. E. Heath 1 Canterbury Heritage A to Z An Encomium in honour of Professor Jackie Eales and Professor Peter Vujakovic Contributions edited by S. Sweetinburgh & D. E. Heath Copyright held by individual contributors Designed by D. E. Heath Centre for Kent History & Heritage, Canterbury Christ Church University, Canterbury CT1 1QU 2020 Contents Encomium 5 A is for St Augustine by Jeremy Law 6 B is for Baobab by Sadie Palmer 8 C is for Cathedral by Cressida Williams 10 D is for Dunstan by Diane Heath 12 E is for Elizabeth Elstob by Jackie Eales 14 E is also for Education and Eales by Lorraine Flisher 16 F is for Folklore and Faery by Jane Lovell 18 G is for Graffiti by Peter Henderson 20 H is for Herbal by Philip Oosterbrink 22 I is for Ivy by Peter Vujakovic 24 J for Jewry by Dean Irwin 26 J is also for Jewel by Lorraine Flisher 28 K is for Knobs and Knockers by Peter Vujakovic 30 L is for Literature by Carolyn Oulton 32 M is for Mission, Moshueshue, McKenzie, and Majaliwa by Ralph Norman 34 N is for Naturalised by Alexander Vujakovic 36 O is for Olfactory by Kate Maclean 38 P is for Pilgrims by Sheila Sweetinburgh 40 P is also for Phytobiography by Chris Young 42 Q is for Queen Eleanor by Louise Wilkinson 44 R is for Riddley Walker by Sonia Overall 46 S is for St Martin’s by Michael Butler 48 T is for Tradescant by Claire Bartram 50 U is for Undercroft by Diane Heath 52 V is for Via Francigena by Caroline Millar 54 V is also for Variety by Chris Young 56 W is for Wotton by Claire Bartram 58 X is for Xylophage by Joe Burman 60 Y is for Yew by Sheila Sweetinburgh 62 Z is for Zyme by Lee Byrne 64 Map of Canterbury (1588) 66 4 Encomium The on-line Christ Church Heritage A to Z celebrated the thirtieth anniversary of the inscription of the Canterbury UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019. -

A History of St. Augustine's Monastery, Canterbury

H Distort of St Huaustine's Monastery Canterbury. BY The Reverend R. J. E. BOGGIS, B.D. Sub- Warden of St. A ugustinfs College. Canterbury : CROSS & JACKMAN, 1901. PREFACE. Churchman or the Antiquarian cannot but feel THEa pang of regret as he turns over the pages of such a work as Dugdale's Monasticon, and notes the former glories of the Religious Houses of England before the hand of the spoliator, had consigned them to desecration and ruin. Some of these homes of religion and learning have entirely disappeared, while others are represented by fragments of buildings that are fast crumbling to decay; and among these latter possibly even among the former would have been counted St. Augustine's, had it not been for the pious and public-spirited action of Mr. A. J. Beresford Hope, who in 1844 purchased part of the site of the ancient Abbey, and gave it back to the Church of England with its buildings restored and adapted for the require- ments of a Missionary College. The outburst of en- thusiasm that accompanied this happy consummation of the efforts of the Reverend Edward Coleridge is still remembered not a few devout Church by people ; and there are very many besides, who rejoice in the fresh lease of life that has thus been granted to the PREFACE. old Foundation, and are interested in the service that is now being here rendered to the English Church of modern times. Such persons may like to have the opportunity of tracing the varied fortunes of the St. Augustine's of former ages, and I have therefore en- deavoured to set forth a sketch of its history during the 940 years of its existence as a Religious House, till the day when the Crown took possession of the Church's property, and "St. -

Royal Marriage and Conversion in Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis

This is a repository copy of Royal Marriage and Conversion in Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum . White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/115475/ Version: Accepted Version Article: MacCarron, M. (2017) Royal Marriage and Conversion in Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum. Journal of Theological Studies, 68 (2). pp. 650-670. ISSN 0022-5185 https://doi.org/10.1093/jts/flx126 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Journal of Theological Studies following peer review. The version of record Máirín MacCarron; Royal Marriage and Conversion in Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, The Journal of Theological Studies, Volume 68, Issue 2, 1 October 2017, Pages 650–670 is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jts/flx126 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Journal of Theological Studies forthcoming 2018 (accepted for publication November 2016) Royal Marriage and Conversion in Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica gentis anglorum Máirín MacCarron Abstract The prevailing view in modern scholarship is that Bede reduced the role of women in his narrative of Anglo-Saxon conversion, in contrast to Gregory of Tours with whom Bede is unfavourably compared. -

Saint Augustine of Canterbury M Iniat Ures from the C.C.C

SAINT AUGUSTINE OF CANTERBURY M INIAT URES FROM THE C.C.C. l\1 .S., CAMBRIDGE, No. 286, TH E SO-CALLED ST. AUGUST INE's GOSPELS. Frontispiece. THE BIRTH OF THE ENGLISH CHURCH SAINT AUGUSTINE OF CANTERBURY BY SIR HENRY H. HOWORTH K.C.I.E,, HoN. D.C.L. (DURHAM), F.R.S., F.S.A., ETC. ETC. PRESlDBNT OF THE ROY. ARCH.. INST. AND THB ROY. NUMISMATIC 5-0CIICTY AUTHOR OF uSAlNT GREGORY THE GREA.T 11 BTC. ETC. WITH ILLUSTRATIONS MAPS, TABLES AND APPENDICES LONDON JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W. 1913 All rights reurv~d TO PROFESSOR WILLIAM BRIGHT AND BISHOP BROWNE OF BRISTOL I WISH to associate the following pages with the names of two English scholars who have done much to illuminate the beginnings of English Church history, and to light my own feet in the dark and unpaved paths across that difficult landscape. I have extolled their works in my Introduction, and I now take off my hat to them in a more formal way. An author's debts can often only be paid by acknowledgment and gratitude. ERRATA. Page 34. For" Christianitas" read" Christianitatis." Page 41, footnote. For" Brown" read" Browne." Page 53. For " 'Povrov,ruu" read "'PoVTov,r,m." Page 65, last line but two. For" though" read "since." PREFACE IN writing a previous work dedicated to the life of Saint Gregory I purposely omitted one of the most dramatic events in his career-namely, the missi?n he sent to Britain to evangelise these islands. My purpose in writing that work was not to publish a · minute and complete monograph of the great Pope. -

How an Early Medieval Historian Worked

How an Early Medieval Historian Worked: Methodology and Sources in Bede’s Narrative of the Gregorian Mission to Kent by Richard Shaw A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Richard Shaw (2014) ii How an Early Medieval Historian Worked: Methodology and Sources in Bede’s Narrative of the Gregorian Mission to Kent Richard Shaw Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines the methods and sources employed by Bede in the construction of his account of the Gregorian mission, thereby providing an insight into how an early medieval historian worked. In Chapter 1, I begin by setting out the context for this study, through a discussion of previous compositional analyses of Bede’s works and the resulting interpretations of the nature and purpose of his library. Chapters 2-4 analyze the sources of the narrative of the Gregorian mission in the Historia ecclesiastica. Each of Bede’s statements is interrogated and its basis established, while the ways in which he used his material to frame the story in the light of his preconceptions and agendas are examined. Chapter 5 collects all the sources identified in the earlier Chapters and organizes them thematically, providing a clearer view of the material Bede was working from. This iii assessment is then extended in Chapter 6, where I reconstruct, where possible, those ‘lost’ sources used by Bede and consider how the information he used reached him. In this Chapter, I also examine the implications of Bede’s possession of certain ‘archival’ sources for our understanding of early Anglo-Saxon libraries, suggesting more pragmatic purposes for them, beyond those they have usually been credited with. -

A Study of Episcopacy in Northumbria 620 - 735

Durham E-Theses A study of episcopacy in Northumbria 620 - 735 Gaunt, Adam How to cite: Gaunt, Adam (2001) A study of episcopacy in Northumbria 620 - 735, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3985/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk A STUDY OF EPISCOPACY IN NORTHUMBRIA 620 - 735 ADAM GAUNT ABSTRACT The Northumbrian people were subject to two different conversions within the space of a single generation. The former was Gregorian in origin, headed by Bishop Paulinus and the latter was lonan, being led by Bishop Aidan. The result was that the Northumbrian church became a melting pot where these two traditions met. The aim of this study is to look again at the early days of the Northumbrian church; however, this study does so by considering the styles of episcopacy employed by the missionary bishops. -

The Laws of Ęthelberht of Kent, the First Page of the Only Manuscript Copy, the Textus Roffensis, from the Collection of the De

SEC. 2D ÆTHELBERHT’S “CODE” II–23 The laws of Æthelberht of Kent, the first page of the only manuscript copy, the Textus Roffensis, from the collection of the Dean and Chapter of Rochester Cathedral, now housed in the Kent County Archives in Maidstone. The photograph is from the frontispiece of H. G. Richardson and G. O. Sayles, Law and Legislation from Æthelberht to Magna Carta (Edinburgh, 1966). II–24 THE AGE OF TORT: ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND SEC. 2 D. ÆTHELBERHT’S “CODE” in LISI OLIVER, THE BEGINNINGS OF ENGLISH LAW 60–81 (Toronto, 2002)† [footnotes renumbered] Þis syndon þa domas þe Æðelbirht cyning asette on AGustinus dæge.1 1. Godes feoh 7 ciricean XII gylde. [1] 2. Biscopes feoh XI gylde. 3. Preostes feoh IX gylde. 4. Diacones feoh VI gylde. 5. Cleroces feoh III gylde. 6. Ciricfriþ II gylde. 7. M[æthl]friþ2 II gylde. 8. Gif cyning his leode to him gehateþ 7 heom mon þær yfel gedo, II bóte, 7 cyninge L scillinga. [2] 9. Gif cyning æt mannes ham drincæþ 7 ðær man lyswæs hwæt gedo, twibote gebete. [3] 10. Gif frigman cyninge stele, IX gylde forgylde. [4] 11. Gif in cyninges tune man mannan of slea, L scill gebete. [5] 12. Gif man frigne mannan of sleahþ, cyninge L scill to drihtinbeage. [6] † Copyright © The University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002. Boldface in the Anglo-Saxon text indicates that the scribe has decorated the upper-case letter. Although he is not totally consistent, this is a good clue to what he regarded as separate clauses.