"The Raha Beach Waterfront Project in Abu Dhabi"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Megaprojects-Based Approach in Urban Planning: from Isolated Objects to Shaping the City the Case of Dubai

Université de Liège Faculty of Applied Sciences Urban Megaprojects-based Approach in Urban Planning: From Isolated Objects to Shaping the City The Case of Dubai PHD Thesis Dissertation Presented by Oula AOUN Submission Date: March 2016 Thesis Director: Jacques TELLER, Professor, Université de Liège Jury: Mario COOLS, Professor, Université de Liège Bernard DECLEVE, Professor, Université Catholique de Louvain Robert SALIBA, Professor, American University of Beirut Eric VERDEIL, Researcher, Université Paris-Est CNRS Kevin WARD, Professor, University of Manchester ii To Henry iii iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My acknowledgments go first to Professor Jacques Teller, for his support and guidance. I was very lucky during these years to have you as a thesis director. Your assistance was very enlightening and is greatly appreciated. Thank you for your daily comments and help, and most of all thank you for your friendship, and your support to my little family. I would like also to thank the members of my thesis committee, Dr Eric Verdeil and Professor Bernard Declève, for guiding me during these last four years. Thank you for taking so much interest in my research work, for your encouragement and valuable comments, and thank you as well for all the travel you undertook for those committee meetings. This research owes a lot to Université de Liège, and the Non-Fria grant that I was very lucky to have. Without this funding, this research work, and my trips to UAE, would not have been possible. My acknowledgments go also to Université de Liège for funding several travels giving me the chance to participate in many international seminars and conferences. -

The World at Your Feet. Info@Messe–Me.Com Tel

The venue The Dubai International Convention and Exhibition Centre has become the most successful venue in the Middle East. With its state of the art facilities, its easy access to and from the airport, shops, restaurants and hotels, it is the ideal setting for the DOMOTEX middle east 2006 carpets and floor coverings exhibition. Dubai - Centre of industrial development The development of the first Free Zone 20 years ago was an important step in creating the future of Dubai. Today, the Jebel Ali Free Zone is the biggest Free Zone in the Middle East with more than 8,000 registered companies. Newer Free Zones such as Media City, Internet City and Knowledge Village are rapidly growing due to the increase in demand from the outside world. Soon, Dubai will develop Free Zones for publishing, printing, manufacturing and Bio-technology to meet the needs of its consumers as well as to maintain its key position amongst rest of the world. The city has a healthy mixture of small and middle-sized businesses as well as wholesale and retail on many different levels. Dubai actually hosts more than one million people from over 130 different countries, with an expatriate rate of more than 70 percent. What has assisted in the region's growth is a newly formed law, enabling expatriates to purchase their own property. This has increased the number of investors and expatriates establishing their private homes here in the UAE, from all over the world. Booking details Space only – USD $315 per square metre. Shell Scheme – USD $365 per square metre. -

List of Hospital Providers Within UAE for Daman's Health Insurance Plans

List of Hospital Providers within UAE for Daman ’s Health Insurance Plans (InsertDaman TitleProvider Here) Network - List of Hospitals within UAE for Daman’s Health Insurance Plans This document lists out the Hospitals available in the Network for Daman’s Health Insurance Plan (including Essential Benefits Plan, Classic, Care, Secure, Core, Select, Enhanced, Premier and CoGenio Plan) members. Daman also covers its members for other inpatient and outpatient services in its network of Health Service Providers (including pharmacies, polyclinics, diagnostic centers, etc.) For more details on the other health service providers, please refer to the Provider Network Directory of your plan on our website www.damanhealth.ae or call us on the toll free number mentioned on your Daman Card. Edition: October 01, 2015 Exclusive 1 covers CoGenio, Premier, Premier DNE, Enhanced Platinum Plus, Enhanced Platinum, Select Platinum Plus, Select Platinum, Care Platinum DNE, Enhanced Gold Plus, Enhanced Gold, Select Gold Plus, Select Gold, Care Gold DNE Plans Comprehensive 2 covers Enhanced Silver Plus, Select Silver Plus, Enhanced Silver, Select Silver Plans Comprehensive 3 covers Enhanced Bronze, Select Bronze Plans Standard 2 covers Care Silver DNE Plan Standard 3 covers Care Bronze DNE Plan Essential 5 covers Core Silver, Secure Silver, Core Silver R, Secure Silver R, Core Bronze, Secure Bronze, Care Chrome DNE, Classic Chrome, Classic Bronze Plans 06 covers Classic Bronze and Classic Chrome Plans, within Emirate of Dubai and Northern Emirates 08 -

Alreeman Investor Brochure Launch

ALREEMAN INVESTOR BROCHURE LAUNCH ALREEMAN - WHERE YOU TRULY BELONG Blending modernity with tradition, AlReeman celebrates the best of the UAE and beyond. Open to all nationalities, it is the blueprint; the foundations; the very beginnings of the home you’ve always dreamed of. With a single plot of land, you can build an villa just the way you like it. Also. there are exciting opportunities for investors, with a number of land available for commercial builds. AlReeman community offers a choice of amenities designed for convenient, sustainable living. All to be enjoyed surrounded by friends and loved ones who share your values and lifestyle choices. 4 TO DUBAI YAS ISLAND LOCATION WARNER BROS. WORLD YAS MALL YAS WATERWORLD FERRARI WORLD YAS LINKS GOLF CLUB ABU DHABI YAS MARINA ABU DHABI E10 SHEIKH ZAYED BIN SULTAN STREET YAS BEACH MOHAMMED BIN RASHID AL MAKTOUM ROAD AL RAHA BEACH AL FALAH ABU DHABI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT MASDAR CITY TO ABU DHABI KHALIFA CITY AL GHAZAL GOLF CLUB E20 INTERNATIONAL ABU DHABI - SWEIHAN - AL HAYER ROAD AIRPORT ROAD SWEIHAN BRIDGE AL ASAYL STABLES SHEIKH ZAYED AL FORSAN INTERNATIONAL GRAND MOSQUE SPORTS RESORT alreeman AL SHAMKHA ALRIYADH CITY CAPITAL DISTRICT E11 ABU DHABI - GHWEIFAT INTERNATIONAL HIGHWAY SHAKHBOUT CITY MUSSAFAH MOHAMMED BIN ZAYED CITY AL SHAWAMEKH AL MAFRAQ AL MAFRAQ HOSPITAL BANI YAS INTRODUCTION • AlReeman is a community that caters to the growing demand for affordable housing in the capital emirate of Abu Dhabi • AlReeman’s vision is to create a luxurious but affordable community that promotes a pedestrian-friendly, sustainable environment where people can live, play and grow in comfort and ease • AlReeman is a mixed-use development that is predominantly residential, with land prepared for villas and apartment buildings. -

Dubai 2020: Dreamscapes, Mega Malls and Spaces of Post-Modernity

Dubai 2020: Dreamscapes, Mega Malls and Spaces of Post-Modernity Dubai’s hosting of the 2020 Expo further authenticates its status as an example of an emerging Arab city that displays modernity through sequences of fragmented urban- scapes, and introvert spaces. The 2020 Expo is expected to reinforce the image of Dubai as a city of hybrid architectures and new forms of urbanism, marked by technologically advanced infrastructural systems. This paper revisits Dubai’s spaces of the spectacle such as the Burj Khalifa and themed mega malls, to highlight the power of these spaces of repre- sentation in shaping Dubai’s image and identity. INTRODUCTION MOHAMED EL AMROUSI Initially, a port city with an Indo-Persian mercantile community, Dubai’s devel- Abu Dhabi University opment along the Creek or Khor Dubai shaped a unique form of city that is con- stantly reinventing itself. Its historic adobe courtyard houses, with traditional PAOLO CARATELLI wind towers-barjeel sprawling along the Dubai Creek have been fully restored Abu Dhabi University to become heritage houses and museums, while their essential architectural vocabulary has been dismembered and re-membered as a simulacra in high-end SADEKA SHAKOUR resorts such as Madinat Jumeirah, the Miraj Hotel and Bab Al-Shams. Dubai’s Abu Dhabi University interest to make headlines of the international media fostered major investment in an endless vocabulary of forms and fragments to create architectural specta- cles. Contemporary Dubai is experienced through symbolic imprints of multiple policies framed within an urban context to project an image of a city offers luxu- rious dreamscapes, assembled in discontinued urban centers. -

Of Abu Dhabi Emirate, United Arab Emirates MARINE and COASTAL ENVIRONMENTS of ABU DHABI EMIRATE, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

of Abu Dhabi Emirate, United Arab Emirates MARINE AND COASTAL ENVIRONMENTS OF ABU DHABI EMIRATE, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES Page . II of Abu Dhabi Emirate, United Arab Emirates Page . III MARINE AND COASTAL ENVIRONMENTS OF ABU DHABI EMIRATE, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES Page . IV MARINE AND COASTAL ENVIRONMENTS OF ABU DHABI EMIRATE, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES H. H. Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan President of the United Arab Emirates Page . V MARINE AND COASTAL ENVIRONMENTS OF ABU DHABI EMIRATE, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES Page . VI MARINE AND COASTAL ENVIRONMENTS OF ABU DHABI EMIRATE, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES H. H. Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces Page . VII MARINE AND COASTAL ENVIRONMENTS OF ABU DHABI EMIRATE, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES Page . VIII MARINE AND COASTAL ENVIRONMENTS OF ABU DHABI EMIRATE, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES H. H. Sheikh Hamdan bin Zayed Al Nahyan Deputy Prime Minister Page . IX MARINE AND COASTAL ENVIRONMENTS OF ABU DHABI EMIRATE, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES s\*?*c*i]j6.%;M"%&9+~)#"$*&ENL`\&]j6. =';78G=%1?%&'12= !"##$" 9<8*TPEg-782#,On%O)6=]KL %&'( )*+,-. 2#,On#X%3G=FON&$4#*.%&9+~)#"$*&XNL %?)#$*&E, &]1TL%&9+%?)':5=&4O`(.#`g-78 %!/ اﻷوراق اﻟﻘﻄﺎﻋﻴﺔ fJT=V-=>?#Fk9+*#$'&= /%*?%=*<(/8>OhT7.F 012(.%34#56.%-78&9+:;(<=>=?%@8'-/ABC $L#01i%;1&&!580.9,q@EN(c D)=EF%3G&H#I7='J=:KL)'MD*7.%&'-(8=';78G=NO D)$8P#"%;QI8ABCRI7S;<#D*T(8%.I7)=U%#$#VW'.X JG&Bls`ItuefJ%27=PE%u%;QI8)aEFD)$8%7iI=H*L YZZ[\&F]17^)#G=%;/;!N_-LNL`%3;%87VW'.X NL]17~Is%1=fq-L4"#%;M"~)#"G=,|2OJ*c*TLNLV(ItuG= )aE0@##`%;Kb&9+*c*T(`d_-8efJG=g-78012 -

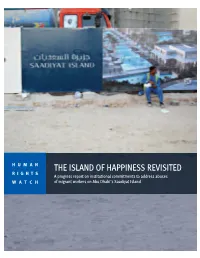

A Progress Report on Institutional Commitments to Address Abuses of Migrant Workers on Abu Dhabi’S Saadiyat Island

HUMAN THE ISLAND OF HAPPINESS REVISITED RIGHTS A progress report on institutional commitments to address abuses WATCH of migrant workers on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island The Island of Happiness Revisited A Progress Report on Institutional Commitments to Address Abuses of Migrant Workers on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island Copyright © 2012 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-870-8 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MARCH 2012 ISBN: 1-56432-870-8 The Island of Happiness Revisited A Progress Report on Institutional Commitments to Address Abuses of Migrant Workers on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island Summary and Key Recommendations ................................................................................. 1 I. Background ................................................................................................................ 13 Human Rights Watch’s 2009 “Island of Happiness” Report .................................................... -

Rezidor Announces Three New Hotels in the UAE Strengthening Its Footprint in the Region

Rezidor announces three new hotels in the UAE strengthening its footprint in the region August 24, 2016 Rezidor, one of the most dynamic hotel companies worldwide and part of the Carlson Rezidor Hotel Group, announces the signing of three new properties in the UAE: the Radisson Blu Hotel, Dubai Waterfront and the Park Inn by Radisson Resort Ras Al Khaimah Marjan Island will already welcome the first guests in Q2-2017. The Radisson Blu Hotel, Dubai Canal View will open its doors in Q1-2018. “The UAE is a key strategic market for us. Dubai, the world’s fourth most visited city in 2015 with 14.2 million overnight visitors has been on an unprecedented growth journey for the last decade. The Emirate’s ambition is to hit 20 million visitors by 2020 and position the country as both a world-class business and leisure destination. We want to contribute to the on-going journey and support this fast-growing sector together with our experienced regional partners”, said Wolfgang M. Neumann, President & CEO of Rezidor. “We are delighted to partner with Mr. Nash’at Farhan Awad Sahawneh and Stallion Properties FZ-LLC. With these three new signings, we are adding over 1,000 rooms to our portfolio in the UAE and further improving our brand awareness in the country, whilst expanding our offering to our guests and further improving the business efficiencies to our investment partners’’, added Elie Younes, Executive Vice President & Chief Development Officer of The Rezidor Hotel Group. The Radisson Blu Hotel, Dubai Waterfront is located in the largest and most impressive waterfront development in the world within Business Bay known as Dubai Water Canal, the new business district of Dubai. -

Island Studies Journal, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2015, Pp. 181-196 Futures, Fakes

Island Studies Journal, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2015, pp. 181-196 Futures, fakes and discourses of the gigantic and miniature in ‘The World’ islands, Dubai Pamila Gupta University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg, South Africa [email protected] ABSTRACT: This article takes the “island” as a key trope in tourism studies, exploring how ideas of culture and nature, as well as those of paradise (lost) are central to its interpretation for tourists and tourist industries alike. Increasingly, however, island tourism is blurring the line between geographies of land and water, continent and archipelago, and private and public property. The case of ‘The World’ islands mega project off the coast of Dubai (UAE) is used to chart the changing face and future of island tourism, exploring how spectacle, branding and discourses of the gigantic, miniature, and fake, alongside technological mediations on a large- scale, reflect the postmodern neoliberal world of tourism and the liquid times in which we live. Artificial island complexes such as this one function as cosmopolitan ‘non-places’ at the same time that they reflect a resurgence in (British) nascent nationalism and colonial nostalgia, all the whilst operating in a sea of ‘junkspace’. The shifting cartography of ‘the island’ is thus mapped out to suggest new forms of place-making and tourism’s evolving relationship to these floating islandscapes. Keywords : archipelago; culture; Dubai; island tourism; nature; ‘World Islands’ © 2015 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Introduction A journey. A saga. A legend. The World is today’s great development epic. An engineering odyssey to create an island paradise of sea, sand and sky, a destination has arrived that allows investors to chart their own course and make the world their own. -

Schützenfest in Dubai

Nr. 17 JULI · AUGUST 2009 Juli · August 2009 Schützenfest in Dubai Super Mario schießt Deutschland zum Sieg Die höchsten Wasserspiele der Welt Dubai Fountain Eine gemeinsame und schlagkräftige Interessenvertretung Gründung der Deutsch-Emiratischen Industrie- und Handelskammer Traumurlaub im Die besten Tipps für die heiße Jahreszeit Die besten Tipps Indischen Ozean Reisetipp: Seychellen Die besten Tipps für die heiße Jahreszeit Sommer in den Emiraten Sommer Nr. 17 Nr. in den Foto: Spa, The Address, Downtown Burj Dubai Emiraten It passes through many hands before it‘s fit to be worn on yours. The Lady Serenade Chronograph - Rose Gold. Every Glashütte Original is painstakingly made by hand to create the most exquisite timepieces that will grace your hands. Like the Lady Serenade Chronograph. Enwrapped in a 38 mm rose gold case, this classic chronograph is both a functional companion for every day wardrobes and an extravagant accessory for formal wear. Find out more about us at www.glashuette-original.com The art of craft. The craft of art. Entdecken Sie neue Märkte Unser Angebot: Verlängerte „VAE-Einführungswochenenden“ in Dubai und Abu Dhabi für Unternehmer, Mittelständler, Existenzgründer und alle Interessenten. www.entdecke-vae.de Entdecke VAE Interkulturelle Seminare für Geschäftsleute EDITORIAL WIRTSCHAFT Jetzt wird’s heiß Sobald die Sommerferien in den Emiraten beginnen, leeren sich die Straßen merklich. Die meis- ten Europäer genießen ihren wohlverdienten Urlaub in heimatlichen Gefilden. Doch in diesem Jahr kehren viele Expat-Familien den VAE für immer den Rücken – in den meisten Fällen jedoch nicht freiwillig. Fluggesellschaften verkaufen vermehrt One-Way-Tickets. Umzugsfirmen sind im Dauerstress. Ziel: Heimat. Zukunft: ungewiss. -

Arkiteknik International & Consulting Engineers I Grand Hyatt Dubai 8 Atkins, KCA International Designers I Burj Al Arab 16

Arkiteknik International & Consulting Engineers I Grand Hyatt Dubai 8 Atkins, KCA International Designers I Burj Al Arab 16 Atkins I Al Mas 24 Atkins I Bright Start Tower 30 Atkins I Chelsea Tower 34 Chapman Taylor, Dewan Architects & Engineers I Pearl Dubai 38 Creative Kingdom, Wilson & Associates I Park Hyatt Dubai 42 Creative Kingdom, KCA International Designers I Madinat Jumeirah 48 Folli Follie I Foili Follie 62 Keith Gavin, Godwin Austen Johnson, Karen Wilhelmm, Mirage Mille I Jumeirah Bab Al Shams 66 Gensler I DIFC Gate Building 80 gmp- von Gerkan, Marg und Partner Architects I Dubai Sports City 84 Joachim Hauser, 3deluxe system modern GmbH I Hydropolis Underwater Resort Hotel 96 Ho+k Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum I Dubai Autodrome 102 Jung Brannen Associates, Dewan Architects & Engineers I Media-1 104 KCA International Designers I Al Mahara 110 KCA International Designers I Arboretum 112 KCA International Designers I Pierchic Restaurant 120 KCA International Designers I Segreto 126 KCA International Designers I Six Senses Spa 136 KCA International Designers I The Wharf 144 Louis Vuitton Malletier Architecture Department I Louis Vuitton 148 Mel McNally Design International I Lotus One 154 Nakheel I Dubai Waterfront 162 NORR Group, Carlos Ott I National Bank of Dubai headquarters 164 NORR Group, Hazel W.S. Wong I Emirates Towers 166 RMJM I AIGurg Tower 174 RMJM I Capital Towers 178 RMJM I Dubai International Convention Centre 180 RMJM I Marina Heights 184 RMJM I The Jewels 186 Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP I Burj Dubai 190 Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP I Sun Tower 194 Wilson & Associates I Givenchy Spa 200 Wilson & Associates I Nina 208 Wilson & Associates I One&Only Royal Mirage 214 Wilson & Associates I Rooftop 224 Wilson & Associates I Traiteur 232 DUBAI ARCHITECTURE & DESIGN daab. -

List of Projects

084-CB-QMS / EMS / OHSMS ISO 9001:2015, ISO 14001:2015 & OHSAS 18001:2007 01-26 01 02 03 05 07 08 09 10 11 13 14 15 24 25 PAGE 01 PAGE 02 PAGE 03 PAGE 04 Abi Baker El Siddique Road Riyadh, KSA Abu Dhabi International Airport - Midfield Terminal Building Abu Dhabi, UAE ADIC Development Tower Abu Dhabi, UAE ADNIC Project Abu Dhabi, UAE ADNOC 7010C1 - Ruwais Housing Complex Expansion Phase IV, New Water Pipeline Abu Dhabi, UAE ADNOC New Medical Centre at Khalidiya Villas Abu Dhabi, UAE Al Bustan Street North (P007 C7 P2) Doha, Qatar Al Furjan Dubai, UAE Al Mafraq Interchange Abu Dhabi, UAE Al Marjan Island Development for Island 3 & 4 Ras Al Khaima, UAE Al Maryah Island Infrastructure Abu Dhabi, UAE Al Ra'idah Housing Complex at Jeddah Riyadh, KSA Al Reef Villas Abu Dhabi, UAE Al Reem Island Development, Plot 4, Central Business District of Plot RT-4-C33, Abu Dhabi, UAE C34, C38 and C39 ADNOC Consultancy Agreement Abu Dhabi, UAE Chilled Water Piping Network at Sector 2 & 3, Canal South & North Side Abu Dhabi, UAE Tamouh, Reem Island Danet Abu Dhabi District Cooling Works Abu Dhabi, UAE Development of Eastern Part of King Abdullah Road Riyadh, KSA Development of Roads in Dubai & All Infrastructure Works Dubai, UAE Dragon Mart Dubai, UAE Eastern Part of King Abdullah Road (P2B1) Riyadh, KSA Eastern Province - Water Transmission System Dammam, KSA Empower Project Dubai, UAE EPC Project with ARAMCO at Eastern Province Riyadh, KSA Falcon Eye Project in 7089 Drive 1 Zone D1 & D2 Abu Dhabi, UAE PAGE 05 Fire Station at Al Meena Abu Dhabi, UAE Ibn Battuta Mall Expansion - E4 & E5 Buildings Dubai, UAE ICAD Project, 992 Abu Dhabi, UAE Infrastructure Project in West Bank Palestine Jerusalem, Palestine Internal Roads and Services in Al Rahba City Abu Dhabi, UAE Lusail Commercial Boulevard - Public Realm Doha, Qatar Mafraq to Al Ghwaifat Border Post Highway Section No.