A Private Matter Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’S Original Love Story by David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin

PRESS RELEASE IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE Twitter | @ModerateSoprano Facebook | @TheModerateSoprano Website | www.themoderatesoprano.com Playful Productions presents Hampstead Theatre’s THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’s Original Love Story By David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin LAST CHANCE TO SEE DAVID HARE’S THE MODERATE SOPRANO AS CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED WEST END PRODUCTION ENTERS ITS FINAL FIVE WEEKS AT THE DUKE OF YORK’S THEATRE. STARRING OLIVIER AWARD WINNING ROGER ALLAM AND NANCY CARROLL AS GLYNDEBOURNE FOUNDER JOHN CHRISTIE AND HIS WIFE AUDREY MILDMAY. STRICTLY LIMITED RUN MUST END SATURDAY 30 JUNE. Audiences have just five weeks left to see David Hare’s critically acclaimed new play The Moderate Soprano, about the love story at the heart of the foundation of Glyndebourne, directed by Jeremy Herrin and starring Olivier Award winners Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll. The production enters its final weeks at the Duke of York’s Theatre where it must end a strictly limited season on Saturday 30 June. The previously untold story of an English eccentric, a young soprano and three refugees from Germany who together established Glyndebourne, one of England’s best loved cultural institutions, has garnered public and critical acclaim alike. The production has been embraced by the Christie family who continue to be involved with the running of Glyndebourne, 84 years after its launch. Executive Director Gus Christie attended the West End opening with his family and praised the portrayal of his grandfather John Christie who founded one of the most successful opera houses in the world. First seen in a sold out run at Hampstead Theatre in 2015, the new production opened in the West End this spring, with Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll reprising their original roles as Glyndebourne founder John Christie and soprano Audrey Mildmay. -

Peter Bramhill Photo: Matt Hussey

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Peter Bramhill Photo: Matt Hussey Height: 5'9" (175cm) Other: Equity Playing Age: 35 - 45 years Eye Colour: Blue-Grey Appearance: Scandinavian, White Hair Colour: Blond(e) Television 2019, Television, Man In Park, Alabama, BBC, Jim O'Hanlon 2017, Television, Mark Lumsden, Holby City, BBC, Various Directors 2016, Television, Arnold Sommerfeld, Genius: Einstein, Fox21 Television Studios, National Geographic, Kevin Hooks 2016, Television, Pilot, No Offence, Abbott Vision Channel 4, Rob Quinn 2016, Television, Gregory Garrod, Doctors, BBC 2015, Television, Greg Collins, New Tricks, BBC, David Innes-Edwards 2013, Television, Richard Wright, Doctors, BBC, Dave Beauchamp 2013, Television, Felix Underwood, Father Brown, BBC, Matt Carter Television, Thomas Blakeway, The Wickedest City, Wall To Wall, Diene Petterle Television, Oliver Young, Vexed, BBC/Greenlit, Matt Lipsey Television, Rev Able Lunn, Doctors, BBC Television, Rebecca Gatward Television, P.C. Woods, Dustbin Baby, Kindle entertainment Ltd, Juliet May Television, Uncle Hank, Made With Magic, Fresh One Productions, Keith Rogerson Television, Alistair Childs, Eastenders, BBC Television, Jo Johnson Television, David Standing, The Bill, Talkbackthames TV, Simon Massey Television, Dr Jim O'Brien, Holby City, BBC Television, Ian Jackson Television, Matthew, Footballers Wives, Shed Productions, Julie Edwards Stage Stage, Tony, Dogs Days, Theatre 503, Lisa Cagnacci Stage, James/Mark, -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Lamda.Ac.Uk Review of the Year 1 WELCOME

REVIEW OF THE YEAR 17-18 lamda.ac.uk Review of the Year 1 WELCOME Introduction from our Chairman and Principal. This year we have been focussing on: 2017-18 has been a year of rapid development and growth for LAMDA Our students and alumni continue to be prolific across film, theatre and television • Utilising our new fully-accessible building to its maximum potential and capacity. production, both nationally and internationally; our new building enables us to deliver • Progressing our journey to become an independent Higher Education Provider with degree gold standard facilities in a fully accessible environment; and our progress towards awarding powers. registration as a world-leading Higher Education Provider continues apace. • Creating additional learning opportunities for students through new collaborations with other arts LAMDA Examinations continues to flourish with 2017/18 yielding its highest number of entrants to organisations and corporate partners. date, enabling young people across the globe to become confident and creative communicators. • Widening access to ensure that any potential student has the opportunity to enrol with LAMDA. We hope you enjoy reading about our year. • Extending our global reach through the expansion of LAMDA Examinations. Rt. Hon. Shaun Woodward Joanna Read Chairman Principal lamda.ac.uk Review of the Year 2 OUR PURPOSE Our mission is to seek out, train and empower exceptional dramatic artists and technicians of every generation, so they can make the most extraordinary impact across the world through their work. Our examinations in drama and communications inspire people to become confident, authentic communicators and discover their own voice. Our vision is to be a diverse and engaged institution in every sense, shaping the future of the dramatic arts and creative industries, and fulfilling a vital role in the continuing artistic, cultural and economic success of the UK. -

Scottish Film Locations – Background Information

Scottish film locations – background information ‘Landscape as Inspiration: Scottish Locations in Literary Work and Film’ To view the full project visit the Scran website at www.scran.ac.uk and search for 0919 in project. "Chariots Of Fire" 1 Looking over the West Sands, St. Andrews, Fife, as featured in the film "Chariots Of Fire" (1981). It is on the beach pictured here that the British Olympic Running team are seen training in preparation for the 1924 Olympics in Paris. It is an example where the Scottish landscape is used to realise a place that is elsewhere- the scene is actually meant to be Broadstairs in Kent. "Chariots Of Fire" is the true story of two British track athletes competing in the 1924 Olympic Games. Eric Liddell is a devout Scottish missionary who runs for God whilst Harold Abrahams is a Jewish student who runs for fame and to escape prejudice for his religious beliefs. Extensive use of Scottish locations were used in the making of the film. The 1981 film, "Chariots of Fire" was directed by Hugh Hudson. It starred Ben Cross as Harold Abrahams and Ian Charleson as Eric Liddell. It was a critical and box office. The opening and closing scenes of the runners on the beach at St. Andrews have become an iconic movie moment, helped by the triumphal background music by Vangelis. ©Neil Sinclair "Gregory's Girl" Looking over a football pitch to Abronhill High School, Cumbernauld, North Lanarkshire, as featured in the film, "Gregory's Girl" (1981). This film tells the story of gangling schoolboy, Gregory, who is just beginning to find out about girls. -

Iain Robertson

22 Astwood Mews, London, SW7 4DE CDA +44 (0)20 7937 2749|[email protected] IAIN ROBERTSON HEIGHT: 5’8 HAIR: Black EYES: Hazel VEHICLE LICENCES: Full Driving Licence Iain received a Scottish BAFTA for Gillies Mackinnon’s ‘Small Faces’. He has been nominated for the Ian Charleson Award twice, receiving a commendation for Bill Bryden’s ‘Mysteries’ trilogy, and third prize for Michael Grandage’s ‘The Tempest’. THEATRE LAST FERRY TO DUNOON ‘Johnaboy’ Dir. David Hayman Jr. [Òran Mór] ON THE SIDELINES ‘John’ Dir. Gilles MacKinnon (Òran Mór) VLAD THE IMPALER ‘Aga Carasol/Dragavei/Dan/Painter/Impaled Romanian’ Dir. Faynia Williams (Òran Mór) THE BRIDGE ‘Davy’ Dir. Donna Franceschild (Òran Mór) FRANK’S DEAD ‘Neil’ Dir. Graeme Maley (Òran Mór) SHANG-A-LANG ‘Carl’ Dir. Michael Emans (Rapture Theatre) THE GREAT TRAIN RACE ‘Cammie’ Dir. Rob Jones (Òran Mór and Lemon Tree, Aberdeen) BREAKER ‘Danny’ Dir. Graeme Maley (Sodid Svid Company at Underbelly, Edinburgh Festival) CLASSIC CUTS: THE TAMING OF THE SHREW ‘Petruchio’ Dir. Rosie Kellagher (Òran Mór) TAKIN’ OVER THE ASYLUM ‘Eddie’ Dir. Mark Thompson (Lyceum Edinburgh / Citizens Glasgow) Nominated Best Male Performance, Critics’ Awards for Theatre in Scotland 2012 - 2013 TAKE ME IF YOU NEED ME Dir. Graeme Maley (Òran Mór) ANGELS ‘Nick’ Dir: Graeme Maley (Oran Mor, Glasgow / Traverse, Edinburgh) THE HARD MAN ‘Johnstone/The Bandit’ Dir. Philip Breen (Edinburgh Festival Theatre) MY ROMANTIC HISTORY ‘Tom’ Dir. Lyndsey Turner (Bush Theatre/Sheffield Theatre/Traverse Theatre) LYSISTRATA ‘Cleonice’ Dir. David MacLennan (Òran Mór) CONFESSIONS OF A JUSTIFIED SINNER ‘Gill-Martin’ Dir. Mark Thomson (Royal Lyceum, Edinburgh) HOMECOMING SCOTLAND CELEBRATIONS ‘Robert Burns’ Dir. -

Before-The-Act-Programme.Pdf

Dea F ·e s. Than o · g here tonight and for your Since Clause 14 (later 27, 28 and 29) was an contribution o e Organisation for Lesbian and Gay nounced, OLGA members throughout the country Action (OLGA) in our fight against Section 28 of the have worked non-stop on action against it. We raised Local Govern en Ac . its public profile by organising the first national Stop OLGA is a a · ~ rganisa ·o ic campaigns The Clause Rally in January and by organising and on iss es~ · g lesbians and gay e . e ber- speaking at meetings all over Britain. We have s ;>e o anyone who shares o r cancer , lobbied Lords and MPs repeatedly and prepared a e e eir sexuality, and our cons i u ion en- briefings for them , for councils, for trade unions, for s es a no one political group can take power. journalists and for the general public. Our tiny make C rre ly. apart from our direct work on Section 28, shift office, staffed entirely by volunteers, has been e ave th ree campaigns - on education , on lesbian inundated with calls and letters requ esting informa cus ody and on violence against lesbians and gay ion and help. More recently, we have also begun to men. offer support to groups prematurely penalised by We are a new organisation, formed in 1987 only local authorities only too anxious to implement the days before backbench MPs proposed what was new law. then Clause 14, outlawing 'promotion' of homosexu The money raised by Before The Act will go into ality by local authorities. -

THE BIRTHDAY PARTY by Harold Pinter Directed by Ian Rickson

PRESS RELEASE – Tuesday 6th March 2018 IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE @BdayPartyLDN / TheBirthdayParty.London Sonia Friedman Productions in association with Rupert Gavin, Tulchin Bartner Productions, 1001 Nights Productions, Scott M. Delman present THE BIRTHDAY PARTY By Harold Pinter Directed by Ian Rickson CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED 60th ANNIVERSARY REVIVAL OF THE BIRTHDAY PARTY ENTERS FINAL WEEKS AT THE HAROLD PINTER THEATRE STRICTLY LIMITED WEST END RUN STARRING TOBY JONES, STEPHEN MANGAN, ZOË WANAMAKER AND PEARL MACKIE MUST COME TO AN END ON 14TH APRIL Audiences now have just five weeks left to see the critically acclaimed West End production of playwright Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party. The company for the major revival, which runs 60 years since the play’s debut, includes Toby Jones, Stephen Mangan, Zoë Wanamaker, Pearl Mackie, Tom Vaughan-Lawlor and Peter Wight, and is directed by Ian Rickson. Stanley Webber (Toby Jones) is the only lodger at Meg (Zoë Wanamaker) and Petey Boles’ (Peter Wight) sleepy seaside boarding house. The unsettling arrival of enigmatic strangers Goldberg (Stephen Mangan) and McCann (Tom Vaughan-Lawlor) disrupts the humdrum lives of the inhabitants and their friend Lulu (Pearl Mackie), and mundanity soon becomes menace when a seemingly innocent birthday party turns into a disturbing nightmare. Truth and alliances hastily shift in Pinter's brilliantly mysterious dark-comic masterpiece about the absurd terrors of the everyday. The production is designed by the Quay Brothers, with lighting by Hugh Vanstone, music by Stephen Warbeck, sound by Simon Baker, and casting by Amy Ball. For more information visit TheBirthdayParty.London -ENDS- For further information please contact The Corner Shop PR on 020 7831 7657 Maisie Lawrence [email protected] / Ben Chamberlain [email protected] LISTINGS Sonia Friedman Productions in association with Rupert Gavin, Tulchin Bartner Productions, 1001 Nights Productions, Scott M. -

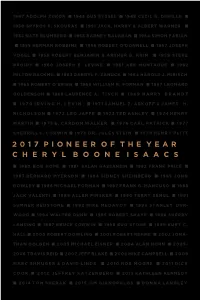

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner. -

University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue 07 | Autumn 2008

University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue 07 | Autumn 2008 Title Palimpsest, Pasolini, Poe and Poetics, or the phantoms haunting Dario Argento’s Opera (1987) Author Keith Hennessey Brown Publication FORUM: University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue Number 07 Issue Date Autumn 2008 Publication Date 12/12/2008 Editors Jack Burton & Jana Funke FORUM claims non-exclusive rights to reproduce this article electronically (in full or in part) and to publish this work in any such media current or later developed. The author retains all rights, including the right to be identified as the author wherever and whenever this article is published, and the right to use all or part of the article and abstracts, with or without revision or modification in compilations or other publications. Any latter publication shall recognise FORUM as the original publisher. Palimpsest, Pasolini, Poe and Poetics, or the phantoms haunting Dario Argento’s Opera (1987) Keith Hennessey Brown University of Edinburgh Italian horror and thriller auteur Dario Argento’s films are replete with images and themes of haunting: the solidified residue of malign, murderous thoughts sensed by the medium at the parapsychology conference which opens Profondo Rosso (1975) or the literal haunted houses inhabited by the witches Mater Tenebrarum, Suspiriorum and Lachrymarum in the horror films Suspiria (1977) and Inferno (1980). Above all, Argento’s gialli – i.e. Italian-style thrillers – from The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970) onwards present a succession of protagonists who find themselves haunted by some vital fragment of sound or image that they cannot quite recall, going up against antagonists whose inability to overcome the haunting legacy of some incident in their past compels them to kill again and again.