New Financial Stability Governance Structures and Central Banks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lelov: Cultural Memory and a Jewish Town in Poland. Investigating the Identity and History of an Ultra - Orthodox Society

Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Item Type Thesis Authors Morawska, Lucja Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 19:09:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7827 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Lucja MORAWSKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 i Lucja Morawska Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Key words: Chasidism, Jewish History in Eastern Europe, Biederman family, Chasidic pilgrimage, Poland, Lelov Abstract. Lelov, an otherwise quiet village about fifty miles south of Cracow (Poland), is where Rebbe Dovid (David) Biederman founder of the Lelov ultra-orthodox (Chasidic) Jewish group, - is buried. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Mattos Chassidus on the Massei ~ Mattos Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) MATTOS ~ MASSEI _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah – Mattos Keep Your Word The Torah states (30:3), “If a man takes a vow or swears an oath to G -d to establish a prohibition upon himself, he shall not violate his word; he shall fulfill whatever comes out of his mouth.” In relation to this passuk , the Midrash quotes from Tehillim (144:4), “Our days are like a fleeting shadow.” What is the connection? This can be explained, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, according to a Gemara ( Nedarim 10b), which states, “It is forbidden to say, ‘ Lashem korban , for G-d − an offering.’ Instead a person must say, ‘ Korban Lashem , an offering for G -d.’ Why? Because he may die before he says the word korban , and then he will have said the holy Name in vain.” In this light, we can understand the Midrash. The Torah states that a person makes “a vow to G-d.” This i s the exact language that must be used, mentioning the vow first. Why? Because “our days are like a fleeting shadow,” and there is always the possibility that he may die before he finishes his vow and he will have uttered the Name in vain. n Story The wood chopper had come to Ryczywohl from the nearby village in which he lived, hoping to find some kind of employment. -

Acharei-Kedoshim

www.Chabad.org offerings, should the Kohen Gadol (“high priest”) purify himself, put on n white linen garments, and enter the chamber housing the Ark: Acharei-KKedoshim He shall take a pan-full of fiery coals from Leviticus 16:1-20:27 atop the altar that is before G-d, and the fill Torah Reading forWeek of April 14-20, 2002 of his hands of finely-ground ketoret (incense), and bring them inside the Parochet. This week’s Torah reading consists of two Parshiot — Acharei Mot (“After the Death”) and Kedoshim (“Holy And he shall place the ketoret upon the fire Ones”). before G-d; and the cloud of incense shall cover up the Kaporet that is on [the Ark of] Following the deaths of Nadav and Avihu, who the Testament... “came close to G-d and died”, G-d tells Moses to instruct Aaron Our Parshah then goes on to detail the service per- formed by the Kohen Gadol on Yom Kippur to secure ...that he should not enter, at all times, into atonement for his people. Among the offerings of the the holy, inside the Parochet (the “veil” that day were two male goats: separated the “Holy of Holies” from the rest of the Sanctuary), before the Kaporet (cover) And Aaron shall cast lots upon the two goats: that is upon the Ark—lest he die; for in a one lot for G-d, and one lot for Azazel. cloud I appear above the Kaporet... The goat that which the lot determined to be “For G- Only on the holiest day of the year—Yom Kippur— d” is brought as an offering and its blood is sprinkled and after bringing a series of specially ordained in the Holy of Holies. -

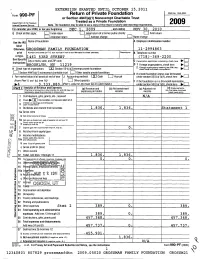

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

EXTENSION GRANTED UNTIL OCTOBER 15,2011 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF a or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2009, or tax year beginning DEC 1, 200 9 , and ending NOV 30, 2010 G Check all that apply: Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity LJ Final return n Amended return n Address chance n Name chance of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS Name label Otherwise , ROSSMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-2994863 print Number and street (or P O box number if mad is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype. 1461 53RD STREET ( 718 ) -369-2200 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exem p tion app lication is p endin g , check here 10-E] Instructions 0 1 BROOKLYN , NY 11219 Foreign organizations, check here ► 2. Foreign aanizations meeting % test, H Check type of organization. ®Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation chec here nd att ch comp t atiooe5 Section 4947(a )( nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation 1 ) E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, co! (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminatio n $ 3 , 333 , 88 0 . -

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the Freevisited Encyclopedi Ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedi ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19 Hasidic Judaism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sephardic pronunciation: [ħasiˈdut]; Ashkenazic , תודיסח :Hasidic Judaism (from the Hebrew pronunciation: [χaˈsidus]), meaning "piety" (or "loving-kindness"), is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that promotes spirituality through the popularization and internalization of Jewish mysticism as the fundamental aspect of the faith. It was founded in 18th-century Eastern Europe by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov as a reaction against overly legalistic Judaism. His example began the characteristic veneration of leadership in Hasidism as embodiments and intercessors of Divinity for the followers. [1] Contrary to this, Hasidic teachings cherished the sincerity and concealed holiness of the unlettered common folk, and their equality with the scholarly elite. The emphasis on the Immanent Divine presence in everything gave new value to prayer and deeds of kindness, alongside rabbinical supremacy of study, and replaced historical mystical (kabbalistic) and ethical (musar) asceticism and admonishment with Simcha, encouragement, and daily fervor.[2] Hasidism comprises part of contemporary Haredi Judaism, alongside the previous Talmudic Lithuanian-Yeshiva approach and the Sephardi and Mizrahi traditions. Its charismatic mysticism has inspired non-Orthodox Neo-Hasidic thinkers and influenced wider modern Jewish denominations, while its scholarly thought has interested contemporary academic study. Each Hasidic Jews praying in the Hasidic dynasty follows its own principles; thus, Hasidic Judaism is not one movement but a synagogue on Yom Kippur, by collection of separate groups with some commonality. There are approximately 30 larger Hasidic Maurycy Gottlieb groups, and several hundred smaller groups. Though there is no one version of Hasidism, individual Hasidic groups often share with each other underlying philosophy, worship practices, dress (borrowed from local cultures), and songs (borrowed from local cultures). -

Financial Stability Governance and Basel III Macroprudential Capital Buffers*

Hutchins Center Working Paper #5 6 January 2020 Financial Stability Governance and Basel III Macroprudential Capital Buffers* Rochelle M. Edge J. Nellie Liang First draft: August 4, 2019 This draft: January 16, 2020 Abstract We evaluate how a country’s governance structure for macroprudential policy affects its implementation of Basel III macroprudential capital buffers. We find that the probabilities of using the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) are higher in countries that have financial stability committees (FSCs) with stronger governance mechanisms and fewer agencies, which reduces coordination problems. These higher probabilities are more sensitive to credit growth, consistent with the CCyB being used to mitigate systemic risk. A country’s probability of using the CCyB is even higher when the FSC or ministry of finance has direct authority to set the CCyB, perhaps because setting the CCyB involves establishing a new macro-financial analytical process to regularly assess systemic risks and allows these new entities to influence the process. These results are consistent with elected officials creating the FSCs with the strongest governance and fewer agencies for functional delegation reasons, but most FSCs are created for symbolic political reasons. * Rochelle M. Edge, Federal Reserve Board, [email protected]; J. Nellie Liang, Brookings Institution, [email protected]. This paper updates an earlier paper “Financial Stability Committees and the Countercyclical Capital Buffer” prepared for the Deutsche Bundesbank, Sveriges Riksbank, and De Nederlandsche Bank Fifth Annual Macroprudential Conference, available at: https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/804686/2bf53d54a90518a3ba524daa5098b565/mL/2019-06-21-eltville-session3- edge-liang-data.pdf. We are grateful for helpful comments from Luca Guerrieri, Michael Kiley, Don Kohn, Andreas Lehnert, Erland Nier, Jean-Charles Rochet, Martin Taylor, and David Wessel. -

Bal Tashchit : the Jewish Prohibition Against Needless Destruction Wolff, K.A

Bal Tashchit : the Jewish prohibition against needless destruction Wolff, K.A. Citation Wolff, K. A. (2009, December 1). Bal Tashchit : the Jewish prohibition against needless destruction. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14448 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14448 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). BAL TASHCHIT: THE JEWISH PROHIBITION AGAINST NEEDLESS DESTRUCTION Copyright © 2009 by K. A. Wolff All rights reserved Printed in Jerusalem BAL TASHCHIT: THE JEWISH PROHIBITION AGAINST NEEDLESS DESTRUCTION Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. mr P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op dinsdag 1 december 2009 klokke 15:00 uur door Keith A. Wolff geboren te Fort Lauderdale (Verenigde Staten) in 1957 Promotiecommissie Promotores: Prof. Dr F.A. de Wolff Prof. Dr A. Wijler, Rabbijn, Jerusalem College of Technology Overige leden: Prof. Dr J.J. Boersema, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Prof. Dr A. Ellian Prof. Dr R.W. Munk, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Prof. Dr I.E. Zwiep, Universiteit van Amsterdam To my wife, our children, and our parents Preface This is an interdisciplinary thesis. The second and third chapters focus on classic Jewish texts, commentary and legal responsa, including the original Hebrew and Aramaic, along with translations into English. The remainder of the thesis seeks to integrate principles derived from these Jewish sources with contemporary Western thought, particularly on what might be called 'environmental' themes. -

The Song My Little Town of Belz

Belz Belz, my little town of Belz בעלז .Pol. Bełz, Ukr. Белз, Yid The little house where I spent my childhood! The songMy Little Town of Belz (version sung by Adam Aston, written by Jacob Jacobs) Princely town ¶ Belz is located the focus of dispute between the rulers near the border with Poland between of Poland, Hungary, and Lithuania. In two tributaries of the Bug River – the 1377–1387, the town came under Hun- Solokiya and Richitsa. According to the garian rule. In 1377, Duke Władysław of most widespread hypothesis, the town’s Opole – the governor of the Palatinate name comes from the Old Slavic bełz or of Ruthenia appointed by King Lajos I of bewz, meaning a muddy, damp area. In Hungary and Poland – granted the town the Boyko dialect, the same word means with the Magdeburg law. In 1387, Queen a muddy place difficult to get through. Jadwiga (Hedwig) of Poland removed Another theory links the town’s name Hungarian palatine from Ruthenia and with an Old Ruthenian word бълизь incorporated that territory into the (a “white place,” a lawn, or clearing, in Kingdom of Poland. A year later, her the midst of a dark forest). ¶ Belz is one husband Władysław II Jagiełło handed of the oldest towns not only in Ukraine, that land over to Siemowit IV, Duke of but also in Eastern Europe. Its first Masovia. In 1462, the town became the mention dates to the Old Rus chronicle capital of Belz Palatinate, created after Tale of the Bygone Years (also known as the incorporation of the Land of Belz the primary Chronicle), which men- into the Polish Crown. -

Tzadik Righteous One", Pl

Tzadik righteous one", pl. tzadikim [tsadi" , צדיק :Tzadik/Zadik/Sadiq [tsaˈdik] (Hebrew ,ṣadiqim) is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous צדיקים [kimˈ such as Biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The root of the word ṣadiq, is ṣ-d- tzedek), which means "justice" or "righteousness". The feminine term for a צדק) q righteous person is tzadeikes/tzaddeket. Tzadik is also the root of the word tzedakah ('charity', literally 'righteousness'). The term tzadik "righteous", and its associated meanings, developed in Rabbinic thought from its Talmudic contrast with hasid ("pious" honorific), to its exploration in Ethical literature, and its esoteric spiritualisation in Kabbalah. Since the late 17th century, in Hasidic Judaism, the institution of the mystical tzadik as a divine channel assumed central importance, combining popularization of (hands- on) Jewish mysticism with social movement for the first time.[1] Adapting former Kabbalistic theosophical terminology, Hasidic thought internalised mystical Joseph interprets Pharaoh's Dream experience, emphasising deveikut attachment to its Rebbe leadership, who embody (Genesis 41:15–41). Of the Biblical and channel the Divine flow of blessing to the world.[2] figures in Judaism, Yosef is customarily called the Tzadik. Where the Patriarchs lived supernally as shepherds, the quality of righteousness contrasts most in Contents Joseph's holiness amidst foreign worldliness. In Kabbalah, Joseph Etymology embodies the Sephirah of Yesod, The nature of the Tzadik the lower descending -

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation JILL

1 t Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service (77) Note : The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state report 2007 For calendar year 2007 , or tax year beginning AUG 1, 2007 , and ending JUL 31 , 2"8 G Check all that annly Initial return Final return Amended return X Address chanae Name channe A Employer identification number Use the IRS Name of foundation label. Otherwise , HE FISHOFF FAMILY FOUNDATION 13-3076576 print Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number or type. 240 VIOLA ROAD--ATTN MIMI 845-352-8070 See Specifi or town, state, and ZIP code C H exemption application is pending , check here Instructions , City ► ONSEY, NY 10952-1731 D 1. Foreign organizations, check here 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, ► H Check typea of organization: Section 501 ()()c 3 exemptP Pprivate foundation check here and attach computation Section trust 0 Other rivate foundation 0 4947(a)(1) nonexem pt charitable taxable p E If private foundation status was terminated Accrual I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Cash under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► = (from Part ll, co!. (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 8 , 7 7 6 , 3 3 5 . -

Randal F. Schnoor TRADITION and INNOVATION in an ULTRA- ORTHODOX COMMUNITY: the HASIDIM of OUTREMONT Hasidic Jewish Communities

52 Roderick Macleod and Mary Anne Poutanen 65When we went to Ste-Sophie in November 2000 in an attempt to locate the synagogue which, according to one source, was still standing, we had difficulty finding anyone who knew that there had once been a Jewish community in the area. The pharmacist, however, remembered an elderly customer whom she believed to be Jewish. Solomon Goodz turned out to live in an old house right across the street from one of the stores where no Randal F. Schnoor one had known there had ever been Jews in Ste-Sophie. Goodz led us to the synagogue, located less than a kilometer from the centre of town. It was still in use, albeit only on the High Holy Days when a rabbi from New York leads TRADITION AND INNOVATION IN AN ULTRA- services for the few locals and some former residents now living Montreal. ORTHODOX COMMUNITY: THE HASIDIM OF 66Sir Wilfrid Laurier School Board Archive, Information Sheet: OUTREMONT “History of Development of Laurentian School Board,” n.d. Hasidic Jewish communities, like other introversionist religious movements such as Hutterites (Boldt, 1989) and Amish or Old Order Mennonites (Kraybill, 1989; Kraybill and Olshan, 1994), are faced with the challenge of preserving their distinctive reli- gious ideals while living within a modern, technologically advanced, capitalist world. Jews in North America in the past century have, for the most part, chosen paths of integration into the general society around them. Studies of Hasidic communi- ties in the 1960s and 1970s (Kranzler, 1961; Poll, 1962; Rubin, 1972; Shaffir, 1974; Mayer, 1979), however, have documented the success of Hasidim in safeguarding their religious convictions and creating and sustaining well-functioning ultra- Orthodox communities in contemporary North America.