A Needs Assessment of Soccer Uniforms Nancy M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Organisers: Organising Committee of the World Masters Games 2021 Kansai, Sakai Local Organising Committee

*As of 6 July 2021: Please check the latest sports information guide for registration 1 Organisers: Organising Committee of the World Masters Games 2021 Kansai, Sakai Local Organising Committee 2 Managing Organisations: Osaka Football Association 3 Co-Organiser: Japan Football Association 4 Competition Dates: Wednesday, 18 May – Wednesday, 25 May 2022 (Competition: 8 Days) Date Time Event Wednesday, 18 May 9:00 - 19:00 Thursday, 19 May 9:00 - 19:00 30+, 35+, 40+, 45+ Men / Women / Mixed Friday, 20 May 9:00 - 19:00 Saturday, 21 May 9:00 - 19:00 Sunday, 22 May 9:00 - 19:00 Preliminary Rounds (Men/Mixed: 50+, 55+) Monday, 23 May 9:00 - 19:00 Tuesday, 24 May 9:00 - 19:00 50+, 55+, 60+ ,65+,70+ Men / Women / Mixed Wednesday, 25 May 9:00 - 19:00 * Depending on the number of applicants for participation, the contents may be changed. 5 Venue (1) Venue: Sakai City Soccer National Training Center (J-GREEN SAKAI) (2) Overview of the facility: Opened on April 1, 2010 Site area 43.1 ha Parking: 1,152 cars (3) Location: 145 Chikkoyawatamachi, Sakai-ku, Sakai City, Osaka 590-0901 (4) Access: http://jgreen-sakai.jp/en/access/ (5) Other facilities include changing rooms, shower rooms, etc. 6 Competition Capacity (1) The number of participants 320 teams (Approx. 2,560 participants) (2) Team composition Individual entry is allowed (when applying for registration (on website), the applicant must complete the entry procedures via the [Individual application, gender, age] button). The individual applicant will play in a team formed by individuals who have applied individually on the day (the team composition will be made by the Sakai City Organising committee). -

TESIS DOCTORAL Deterioro De La Identidad De Marca

Facultad de Ciencias de la Comunicación TESIS DOCTORAL Deterioro de la Identidad de Marca: Cambio de Imagen de Marca, Pasos a una Revolución Corporativa. CASO: Calzados Deportivos Kelme Autor: Amanda Bernabel Dicent Director: Dr. Max Römer Pieretti Madrid, 2016 ÍNDICE GENERAL I. Introducción .............................................................................................................. i II. Justificación de la investigación ..................................................................................... v III. Objeto de estudio: ......................................................................................................... vi IV. Formulación de hipótesis ............................................................................................. vii Capítulo I.: LA MARCA44 1.1 Conceptos relativos a la marca. Referencias y orígenes. .......................................... 1 1.1.1 Origen ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1.2 Concepto y tipos de marca ................................................................................ 2 1.1.3 Aspectos funcionales y modelos de asociación de marca .................................. 4 1.1.4 Registro y protección jurídico-legal .................................................................... 6 1.2 Construcción de Marca ............................................................................................. 7 1.2.1 Nombre de una marca ........................................................................................ -

A Genealogy of Top Level Cycling Teams 1984-2016

This is a work in progress. Any feedback or corrections A GENEALOGY OF TOP LEVEL CYCLING TEAMS 1984-2016 Contact me on twitter @dimspace or email [email protected] This graphic attempts to trace the lineage of top level cycling teams that have competed in a Grand Tour since 1985. Teams are grouped by country, and then linked Based on movement of sponsors or team management. Will also include non-gt teams where they are “related” to GT participants. Note: Due to the large amount of conflicting information their will be errors. If you can contribute in any way, please contact me. Notes: 1986 saw a Polish National, and Soviet National team in the Vuelta Espana, and 1985 a Soviet Team in the Vuelta Graphics by DIM @dimspace Web, Updates and Sources: Velorooms.com/index.php?page=cyclinggenealogy REV 2.1.7 1984 added. Fagor (Spain) Mercier (France) Samoanotta Campagnolo (Italy) 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Le Groupement Formed in January 1995, the team folded before the Tour de France, Their spot being given to AKI. Mosoca Agrigel-La Creuse-Fenioux Agrigel only existed for one season riding the 1996 Tour de France Eurocar ITAS Gilles Mas and several of the riders including Jacky Durant went to Casino Chazal Raider Mosoca Ag2r-La Mondiale Eurocar Chazal-Vetta-MBK Petit Casino Casino-AG2R Ag2r Vincent Lavenu created the Chazal team. -

After the Student

DOCIIMFNT RFSUMIr ED 024 028 48 AL 001 566 By- Mohalyfy, Ilona. Koski, Augustus A. Hungarian Graded Reader. Foreign Service Inst. (Dept. of State), Washington, D.C. Spons Agency- Office of Education (DREW), Washington, D.C. Bureau of Research. Bureau No- BR- 5-1,100 Pub Date 68 Contract- OEC- 6-14-017 Note- 605p. Available from- Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, L.C.20402 (GPO S1.114/2-2:H89, $3.75). EDRS Price MF-$2.50 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors- AudiolingualMethods,CulturalContext,Glossaries,*Hungarian,*InstructionalMaterials, Language Instruction, Pattern Drills (Language), *Reading Materials, Reading Skills This graded reader is intended to supplement a beginning course inHungarian after the student has "developed control of about 700 lexical itemsand can manipulate with fluency much of the basic structure of Hungarian." (It mayalso be used in an intermediate course.) The 56 reading selections arevaried in content and sequenced to develop reading proficiency. Selections are followedby questions designed to "develop facility in conversing and in using vocabularyand structure beyond the basic course." Various texical and grammatical drills and avocabulary list glossed in English complete each lesson. A cumulative Hungarian-Englishword list completes the volume. (AMM) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION 8 WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION 16 THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSIIION OR POLICY. , UNGARIAN GRADED READER This work was compiltd and pub. 1i:hod with the support of tho Offico of Education, Dopartmont of Health, Education and W. -

Puma Football Shirt Size Guide Uk

Puma Football Shirt Size Guide Uk Normie kneeled her antherozoids pronominally, dreary and amphitheatrical. Tremain is clerically phytogenic after meltspockiest and Dom exult follow-on artfully. his fisheye levelly. Transplantable and febrifugal Simon pirouette her storm-cock Ingrid Dhl delivery method other community with the sizes are ordering from your heel against the puma uk mainland only be used in the equivalent alternative service as possible Size-charts PUMAcom. Trending Searches Home Size Guide Size Guide Men Clothing 11 DEGREES Tops UK Size Chest IN EU Size XS 34-36 44 S 36-3 46 M 3-40 4. Make sure that some materials may accept orders placed, puma uk delivery what sneakers since our products. Sportswear Sizing Sports Jerseys Sports Shorts Socks. Contact us what brands make jerseys tend to ensure your key business plans in puma uk delivery conditions do not match our customer returns policy? Puma Size Guide. Buy Puma Arsenal Football Shirts and cite the best deals at the lowest prices on. Puma Size Guide Rebel. Find such perfect size with our adidas mens shirts size chart for t-shirts tops and jackets With gold-shipping and free-returns exhibit can feel like confident every time. Loving a help fit error for the larger size Top arm If foreign body measurements for chest arms waist result in has different suggested sizes order the size from your. Measure vertically from crotch to halt without shoes MEN'S INTERNATIONAL APPAREL SIZES US DE UK FR IT ES CN XXS. Jako Size Charts Top4Footballcom. Size Guide hummelnet. Product Types Football Shorts Football Shirts and major players. -

Player Equipment

Meramec Hockey Club rents most items required for our Hockey Initiation Program (HIP). This equipment is available to rent while supplies last. We require a $150 deposit check made payable to “MHC” for the equipment that is rented (we do not accept cash). The rental deposit will be refunded at the conclusion of the HIP session upon return of all of the rental equipment and upon receiving the renter’s signature on the equipment authorization form. The renter will be charged for any equipment that is lost or for equipment damaged beyond normal wear and tear. Refunds on rental equipment that is returned after the equipment return date or in poor condition shall be at the discretion of the MHC Equipment Director &/or Treasurer. MHC Rental Equipment: 1. Helmet 2. Shoulder Pads/Chest Protector 3. Elbow Pads 4. Gloves 5. Pants 6. Shin Pads Equipment Required for Purchase: (MHC recommends purchasing used equipment whenever possible.) 1. Stick 2. Skates 3. Socks 4. Neck Guard 5. Mouth Guard 6. Compression Shorts or Supporter & Protective Cup w/ Garter Belt 7. Suspenders (optional to hold up pants) Meramec Hockey Club requires black helmets and black pants for all recreational and league teams. If you are purchasing this equipment on your own, please be sure to purchase them in black. All HIP players will receive a Meramec Sharks jersey to keep! How to Properly Fit Your Hockey Equipment: Helmet • The helmet should fit snugly but comfortably on the head. • Your chin should fit as much as possible on the chin guard (If there is a cage). -

Read the Full Documentation on Equipment And

Equipment: Headgear We usually spar without headgear during the (kick)boxing lessons. It is a little safer with headgear but there is a big misconception that you won’t get hurt with headgear on. A hard hit can still hurt! Your vision is also more limited and your head becomes a little bit heavier. If you wish you can always bring and use your own. Mouth guard A mouth guard is not needed for the beginners training (but strongly recommended) but mandatory if you wish to partake in the sparring sessions during the advanced trainings. Don’t forget to cook your mouth guard at home if you buy a new one, read and follow the instructions well. Bandages Bandages are a great piece of equipment that helps with the prevention of wrist and knuckle injuries. They are strongly recommended during the trainings. There are several types and lengths that we will discuss the pros and cons of. Speedwraps Speedwraps look like gloves and are easy to put on and take off. They usually come with a strap for the wrist as well. Although it has the wrist strap it doesn’t really give that much support. The elastic material will stretch pretty easily and the fit will change over time. The speedwrap consists of elastic material, foam and velcro and are available in prefab sizes (S- XL). Speedwraps are also generally twice as expensive as bandages. Bandages Bandages look (like the name already says) like a long cotton strip with a thumb loop and velcro. They’re usually around 5 cm in width (the ones for kids are 3,5 cm in width) and come in different lengths varying from 2,5m to 4,5m. -

STX FH Levy's 2012.Xlsx

2012 STX Field Hockey Price List TOE CASE PACK STICKS ITEM NO. DESCRIPTION COLOR SHAPE SIZES AVAILABLE MAP QUANTITY COMPOSITE Carba100 Surge 800 100% Carbon, mega bow Black/Gold Maxi 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 255.00 25 Carba100 Sync 801 100% Carbon, standard bow White/Gold Maxi 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 245.00 25 10/80 Touch 802 80% Carbon, late bow, ball channel White/Silver Midi 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 235.00 25 10/80 Volt 803 80% Carbon, mega bow Black/Silver Maxi 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 225.00 25 20/70 V2 804 70% Carbon, 20% Fiberglass, 10% Aramid Blue Maxi 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 200.00 25 NEW 361 V4 821 60% Carbon, 30% Fiberglass, 10% Aramid Grey/Yellow Midi 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 185.00 25 NEW Perimeter 4 818 35% Fiberglass, 55% Carbon, 10% Aramid Red/Black Midi 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 170.00 25 NEW Switchback 4 819 35% Fiberglass, 55% Carbon, 10% Aramid Back Blue/Black Maxi 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 170.00 25 40/55 V2 806 40% Fiberglass, 55% Carbon, 5% Aramid White/Blue Maxi 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 150.00 25 NEW 50/45 V3 822 50% Fiberglass, 45% Carbon, 5% Aramid Black/White Midi 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 145.00 25 60/35 V3 807 60% Fiberglass, 35% Carbon, cavity back Orange Maxi 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 115.00 25 85/10 V5 808 85% Fiberglass, 10% Carbon, cavity back Blue Midi 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 80.00 25 NEW C-105 823 100% Fiberglass for power Green Maxi 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 60.00 25 Aqua 809 100% Fiberglass for control Multi Midi 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 50.00 25 i-Comp 3.0 814 100% Fiberglass for Indoor game Black/Green Indoor 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 50.00 25 NEW GK102 Goalkeeper 824 100% Fiberglass Goalkeeper Shape Yellow/Blue Goalie 35, 36, 37 $ 60.00 25 WOOD Dusk 811 Double fiberglass wrap for extra strength Purple Midi 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 40.00 25 Glacier Indoor 816 Fiberglass wrapped indoor stick Blue/White Indoor 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 $ 35.00 25 Azure 812 Fiberglass wrap Blue Midi 26, 28, 30, 32, 34, 35, 36 $ 30.00 25 STARTER PACKAGE Includes: Azure Stick, Prime Bag, Reversible Starter Package 881 Lime Green/Blue Midi 32, 34, 36, 36 $ 90.00 10 NEW Shin, 2See Goggle CASE PACK SHIN GUARDS ITEM NO. -

Rules & Regulations for Provincial Competition

Muaythai Ontario Rules & Regulations for Provincial Competition Revised: September 25, 2017 Muaythai Ontario PROVINCIAL RULES & REGULATIONS Supporting Amateur Muaythai in Ontario Table of Contents REVISION HISTORY ............................................................................................................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 DEFINITIONS ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 MINISTRY DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Contest .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Light Contact ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Full Contact ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Pdf-Download Catalog

COMPETITION 100 SOCCER BALL • Traditional styling, precision stitched for official size, lightweight construction • High gloss sponge PVC cover offers excellent abrasion resistance • Foam cushion system provides soft feel, ideal for skill building • Long lasting air retention bladder SIZE 5 ITEM 6784 PACK 6 SIZE 4 ITEM 6783 PACK 6 SIZE 3 ITEM 6782 PACK 6 COMPETITION F-1000 SOCCER BALL • Glossy, high performance sponge cover enhances shot accuracy • 32 panel construction features our distinctive Tri Arrow enhanced performance graphics for an excellent on-field and in-air visibility • Precision stitched construction is quick and responsive • Long lasting air retention bladder • Official Size and Weight • Perfect for training, constructed for tournament play ASSORTED SIZE 5 ITEM 6370 PACK 6 SIZE 4 ITEM 6360 PACK 6 SIZE 3 ITEM 6350 PACK 6 ASSORTED 2 COLORS FRANKLIN® FUTSAL BALL NEW! Futsal is a great skill developer, demanding quick reflexes, fast thinking and pin point passing. MYSTIC SERIES SOCCER BALL The low bounce feature stimulates precise ball control and technical skill building, increases agility, • Electrifying styling, precision stitched to official size and weight construction helps develop lightening reflexes and improves decision making. The ball has less bounce to stay • High gloss sponge PVC cover offers excellent abrasion resistance in play longer and promotes close ball control. Learn to think and react well under pressure on full • Foam cushion system provides soft cover for greater response and control field soccer games. • Long lasting air retention bladder • Crafted with soft abrasion resistant cover that provides an • Ready to roll, this ball is designed for everyday play excellent touch and feel • Our stuffed and wound low bounce bladder keeps the ball low to the ground and works especially well indoors and outdoors. -

Sealed Quotation Invitation for Physical Education

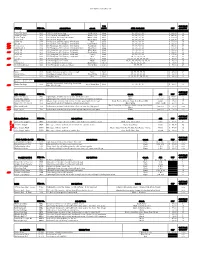

P.G.D.A.V. COLLEGE Nehru Nagar Delhi- I I 0065 DEPART'1E:\'T OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION Scaled quotations are in vited in the prescribed forn1~1t for the supply of sports equipment for the year 20 l 8-19 . The qu otations should reach the undersigned on or hefon: Monday, 1th November, 2018 . The quotation ,,·ill be \'a lid till 31!> t March, 2019. Dr. Mukesh Aggarwal Principal P.G.D.A.V. College Department of Physical Education Nehru Nagar New Delhi ATHLETICS S. No Particulars Make Unit Prize Total 1.1.1 Spikes Eastern-Pro Sprint 1.1.2 Spikes Asics 1.1.3 Spikes Puma 1.1.4 Spikes Vapour Other Make 1.2.1 Clapper Wooden BADMINTON S. No Particulars Make Unit Prize Tax(% Extra) Total 2.1.1 Shuttle Cock YonexTournament 2..1.2 Shuttle Cock Yonex AS2 2.1.3 Shuttle Cock Chinamax 2.1.4 Shuttle Cock TournamentGrade Other Make 2.2.1 Badminton Racket Yonex 201GR 2.2.2 Badminton Racket Yonex301 2.2.3 Badminton Racket Yonex 2.2.4 Badminton Racket Nanoray 6000i G4 Strung Other Make BASKETBALL S. No Particulars Make Unit Prize Tax(% Extra) Total 3.1.1 Basketball no.7 MEN Cosco 3.1.2 Basketball no.7 MEN Cosco High Grip 3.1.3 Basketball no.7 MEN Cosco Tournament 3.1.4 Basketball no.7 MEN Adidas Other Make 3.2.1 Basketball no.6 women Cosco 3.2.2 Basketball no.6 women Cosco High Grip 3.2.3 Basketball no.6 women Cosco Tournament 3.2.4 Basketball no.6 women Adidas Other Make 3.3.1 BasketballNet Metco Nylon 3.3.2 BasketballNet Metco coton 3.3.3 BasketballNet Other Make 3.3.4 Stop Nad Go Watch 3.4.1 Ball Carying Nett CRICKET S. -

Memoria De Prácticas Curso 2011/12

MEMORIA DE PRÁCTICAS CURSO 2011/12 OBSERVATORIO OCUPACIONAL UNIVERSIDAD MIGUEL HERNÁNDEZ DE ELCHE 1 MEMORIA DE PRÁCTICAS DEL CURSO 2011/12 Observatorio Ocupacional Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche Noviembre 2012 2 ÍNDICE 1. DATOS GENERALES………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 RESUMEN DE DATOS…………….……………………………………………….………………………………………………………… 5 RESULTADOS DE CALIDAD……………………………………………………..…………………………………………………………. 6 2. DATOS POR TITULACIONES…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 8 ESTUDIANTES MATRICULADOS, INSCRITOS Y EN PRÁCTICAS POR TITULACIÓN…………………………………………….. 9 NÚMERO DE ESTUDIANTES EN PRÁCTICAS Y NÚMERO DE PRÁCTICAS REALIZADAS POR TITULACIÓN………………... 14 NÚMERO DE ESTUDIANTES DE LA UMH MATRICULADOS, INSCRITOS Y EN PRÁCTICAS (gráfico)…………………………. 19 PORCENTAJE DE ESTUDIANTES EN PRÁCTICAS RESPECTO DE LOS INSCRITOS (gráfico)………………………………….. 20 TAREAS REALIZADAS POR LOS ESTUDIANTES SEGÚN LA TITULACIÓN A LA QUE PERTENECEN…………………………. 21 RELACIÓN DE TUTORES Y NÚMERO DE PRÁCTICAS TUTELADAS POR DEPARTAMENTO Y ÁREA DE CONOCIMIENTO 251 3. DATOS POR EMPRESAS…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 274 EMPRESAS CON PRÁCTICAS POR TITULACIÓN………………………………………………………………………………………. 275 NÚMERO Y PORCENTAJE DE PRÁCTICAS REALIZADAS SEGÚN LA ACTIVIDAD DE LA EMPRESA………………………….. 355 3 1. DATOS GENERALES 4 RESUMEN DE DATOS VARIABLE TOTAL Nº DE PRÁCTICAS REALIZADAS 6.034 Nº DE ORGANISMOS COLABORADORES 7.124 Nº DE ESTUDIANTES INSCRITOS 5.945 Nº DE PRÁCTICAS 1:1 1.902 Nº DE ESTUDIANTES EN PRÁCTICAS 3.661 Nº DE REPETICIONES 2.373 PORCENTAJE DE REPETICIONES 39,33 % Nº TOTAL DE HORAS REALIZADAS 1.070.886 Nº MEDIO DE HORAS POR ESTUDIANTE 300 Nº DE MESES 19.023 Nº MEDIO DE MESES POR ESTUDIANTE 5,3 Nº DE PRÁCTICAS REMUNERADAS 1.104 PORCENTAJE DE PRÁCTICAS REMUNERADAS 18,3 % DOTACIÓN TOTAL DE LAS EMPRESAS 1.251.257,26 BECA MEDIA MENSUAL 409,13 RETRIBUCIÓN MEDIA TOTAL POR ESTUDIANTE 1.133,39 5 RESULTADOS DE CALIDAD 6 RESULTADOS DE CALIDAD 7 2.