The Battle for Bell Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entanglements Between Irish Catholics and the Fishermen's

Rogues Among Rebels: Entanglements between Irish Catholics and the Fishermen’s Protective Union of Newfoundland by Liam Michael O’Flaherty M.A. (Political Science), University of British Columbia, 2008 B.A. (Honours), Memorial University of Newfoundland, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Liam Michael O’Flaherty, 2017 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2017 Approval Name: Liam Michael O’Flaherty Degree: Master of Arts Title: Rogues Among Rebels: Entanglements between Irish Catholics and the Fishermen’s Protective Union of Newfoundland Examining Committee: Chair: Elise Chenier Professor Willeen Keough Senior Supervisor Professor Mark Leier Supervisor Professor Lynne Marks External Examiner Associate Professor Department of History University of Victoria Date Defended/Approved: August 24, 2017 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between Newfoundland’s Irish Catholics and the largely English-Protestant backed Fishermen’s Protective Union (FPU) in the early twentieth century. The rise of the FPU ushered in a new era of class politics. But fishermen were divided in their support for the union; Irish-Catholic fishermen have long been seen as at the periphery—or entirely outside—of the FPU’s fold. Appeals to ethno- religious unity among Irish Catholics contributed to their ambivalence about or opposition to the union. Yet, many Irish Catholics chose to support the FPU. In fact, the historical record shows Irish Catholics demonstrating a range of attitudes towards the union: some joined and remained, some joined and then left, and others rejected the union altogether. -

The Pattern of Glaciation on the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland L’Histoire De La Glaciation De La Presqu’Île D’Avalon, À Terre-Neuve

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 05:31 Géographie physique et Quaternaire The pattern of glaciation on the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland L’histoire de la glaciation de la presqu’île d’Avalon, à Terre-Neuve. Das Schema der Vereisung auf der Avalon-Halbinsel in Neufundland. Norm R. Catto Volume 52, numéro 1, 1998 Résumé de l'article L'histoire de la glaciation de la presqu'île d'Avalon a été établie à partir de URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/004778ar l'étude des caractéristiques géomorphologiques, des stries et de la provenance DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/004778ar des blocs erratiques. On distingue trois phases dans un continuum de glaciation. Pendant la première phase, il y a eu accumulation et dispersion de Aller au sommaire du numéro la glace à partir de plusieurs centres. Au cours de la deuxième période, qui correspond au Wisconsinien supérieur, les glaciers ont atteint un maximum en étendue et en épaisseur. Le niveau marin abaissé a permis la formation d'un Éditeur(s) centre glaciaire à l'emplacement de la baie St. Mary. Le glacier en provenance de la partie continentale de Terre-Neuve a fusionné avec celui de la presqu'île Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal d'Avalon dans la baie de Plaisance, sur l'isthme et dans la baie de la Trinité. La troisième phase, caractérisée par la remontée du niveau marin et déclenchée ISSN par le recul de l'Inlandsis laurentidien au Labrador, a déséquilibré la calotte glaciaire de St. Mary. La déglaciation finale de la presqu'île d'Avalon a 0705-7199 (imprimé) commencé avant 10 100 ± 250 BP. -

CARBONEAR the District of Trinity

TRINITY – CARBONEAR The District of Trinity – Carbonear shall consist of and include all that part of the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador bounded as follows: Beginning at the intersection of the western shoreline of Conception Bay and the Town of Harbour Grace Municipal Boundary (1996); Thence running in a general southwesterly and southeasterly direction along the said Municipal Boundary to its intersection with the Parallel of 47o40’ North Latitude; Thence running due west along the Parallel of 47o40’ North Latitude to its intersection with the Meridian of 53o25’ West Longitude; Thence running due north along the Meridian of 53o25’ West Longitude to its intersection with the Town of Heart’s Delight-Islington Municipal Boundary (1996); Thence running west along the said Municipal Boundary to its intersection with the eastern shoreline of Trinity Bay; Thence running in a general northeasterly and southwesterly direction along the sinuosities of Trinity Bay and Conception Bay to the point of beginning, together with all islands adjacent thereto. All geographic coordinates being scaled and referenced to the Universal Transverse Mercator Map Projection and the North American Datum of 1983. Note: This District includes the communities of Bay de Verde, Carbonear, Hant's Harbour, Heart's Content, Heart's Delight-Islington, Heart's Desire, New Perlican, Old Perlican, Salmon Cove, Small Point-Adam's Cove-Blackhead-Broad Cove, Victoria, Winterton, New Chelsea-New Melbourne-Brownsdale-Sibley's Cove-Lead Cove, Turks Cove, Grates Cove, Burnt Point-Gull Island-Northern Bay, Caplin Cove-Low Point, Job's Cove, Kingston, Lower Island Cove, Red Head Cove, Western Bay-Ochre Pit Cove, Freshwater, Perry's Cove, and Bristol's Hope. -

Report on Harbour Grace People, Places & Culture Workshop

Report on Harbour Grace People, Places & Culture Workshop November 2018 1 Introduction Heritage NL’s program “People, Places & Culture” is designed to assist communities to identify their cultural assets and to consider ways to protect and develop them. It is based on a recognition that heritage/cultural assets are some of the strongest elements that a community has to: define its unique character; create new economic opportunities; and enhance the quality of life for residents and instill local pride. This report represents the output of a “People, Places & Culture” WorKshop facilitated by Heritage NL in Harbour Grace in November 2018 comprising two parts: I) a cultural mapping activity that considered the community’s tangible and intangible cultural assets; and II) a session to explore opportunities for protecting, safeguarding and developing these assets. Workshop Session I: Heritage Assets What Participants Want from the Workshop WorKshop participants expressed that they were attending the session because they wanted to help realize the potential of Harbour Grace’s heritage, much liKe other communities in the province have done. A discussion was held at the start of the session around what participants hoped would come out of the worKshop. Three Key areas were identified by the group: A. Inventorying our Heritage The group identified a need to identify and catalogue what exists in the community, so there is a good record of assets. There is a sense that there is already great material out there, based on previous research, collections, and oral histories, both public and privately owned. How do we find this information and maKe it useful for our town? And then how do we identify themes or areas of focus (church, courthouse, family history, etc.) and undertake new research, such as oral histories, to fill in the gaps? B. -

Put the Child First Reminder

The C.L.B. Contact Directory March 2017 Page 1 Put the Child First Reminder Adult Leaders who have knowledge, or suspect, that one of our youth members has been subjected to any form of abuse must first and foremost report this to Child Protection Services (752-4619) and/or the police, and secondly advise Lieut. Sheila Mercer, Regimental Put The Child First Director (368-1832), that a report has been made. Page 2 Table of Contents Page(s) Brigade Council Armoury Staff ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Council Staff ....................................................................................................................................... 4, 5 Honorary and Retired ........................................................................................................................ 5 Quartermaster’s Stores ...................................................................................................................... 6 Eastern Diocesan Regiment Regimental Staff ................................................................................................................................. 6, 7 C.L.B. Regimental Band ...................................................................................................................... 8 C.L.B. Regimental Corps of Drums......................................................................................................8 Avalon Battalion # 41 Battalion Staff ................................................................................................................................... -

Stories from the Portugal Cove- St. Philip's Memory Mug Up

Stories from the Portugal Cove- St. Philip’s Memory Mug Up Edited by Dale Jarvis and Terra Barrett, & the students of FOLK 6740: Public Folklore Collective Memories Series #06 STORIES FROM THE PORTUGAL COVE- ST. PHILIP’S MEMORY MUG UP Edited by Dale Jarvis, Terra Barrett, & the students of FOLK 6740: Public Folklore Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador Intangible Cultural Heritage Office St. John’s, NL, Canada Layout / design by Jessie Meyer 2017 ntroduction I BY DALE JARVIS In February of 2017, I headed off to Portugal Cove-St. Philip’s with three carloads of graduate folklore students enrolled in FOLK 6740: Public Folklore at Memorial University. We were heading there to host a Memory Mug Up, organized with the help of Julie Pomeroy, the town's Heritage Programs and Services Coordinator. A Memory Mug Up is an informal story sharing session for seniors, where people gather, have a cup of tea, and share memories. The goal of the program is to help participants share and preserve their stories. Julie had spoken to the class before the event, talking about the town’s work to conserve its tangible and intangible heritage. She was interested in information about place names, cemeteries, names of local ponds, fishing history and families, a 1978 plane crash, Bell Island connections, and ghost stories. On that first meeting, we sat around with cups of coffee Background: Student Marissa and tea, studied maps of the Farahbod talks with Diane Morris. Foreground: Students Cassandra community, and shared stories Colman and Ema Kirbirkstis talk about all those things and more. -

Mummers on Trial

Fraser – Newfoundland Mumming MUMMERS ON TRIAL Mumming, Violence and the Law in Conception Bay and St. John’s, Newfoundland, 1831-18631 JOY FRASER Memorial University of Newfoundland St. John's <[email protected]> Abstract This paper investigates the violence surrounding the custom of Christmas mumming as practised in the urban centres of Conception Bay on Newfoundland’s northeast coast, and in the island’s capital, St. John’s, in the mid-19th Century. Until recently, few contemporary accounts have come to light between the first known description of mumming-related violence in this area in January 1831 and the alleged murder of Isaac Mercer by mummers in the town of Bay Roberts in December 1860. This paper argues that the proceedings of several criminal trials involving mummers recently uncovered at the Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador provide significant new evidence of a close relationship between mumming, violence and the law in Conception Bay and St. John’s during this period. The paper also explores the insights that the trial proceedings offer into the practice of mumming itself, the backgrounds of participants and the motivations underlying the violent incidents. In light of this new evidence, I argue for the need to re-examine the links that have been posited between mumming-related violence and the wider social, ethnic, religious and political tensions that affected life in mid-19th Century urban Newfoundland. Keywords mumming, violence, Newfoundland, criminal trials Introduction In recent years, the custom of Christmas mumming has assumed a prominent position within Newfoundland’s cultural iconography. Participants in this custom, as it takes place on the island today, conceal their identities by adopting various disguises and by modifying their speech, posture and behaviour; they then travel in groups from house to house within their communities, where they may entertain their hosts with music and dancing. -

Summary Report Baccalieu Trail Thriving Regions

THE LESLIE HARRIS CENTRE OF REGIONAL POLICY AND DEVELOPMENT SUMMARY REPORT BACCALIEU TRAIL THRIVING REGIONS WORKSHOP #1 Princess Sheila Seniors Building CarBonear SeptemBer 27, 2019 Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 About the Thriving Regions Partnership Process and this Workshop................................................................... 3 Priority Themes ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Next Steps ............................................................................................................................................................. 9 About the Harris Centre ...................................................................................................................................... 10 Appendix A – Baccalieu Trail Thriving Regions Core Planning Team .................................................................. 11 Appendix B – List of Attendees ........................................................................................................................... 12 1 Introduction As part of the Harris Centre’s Thriving Regions Partnership Process, on SeptemBer 27, 2019 the Harris Centre hosted the first in a series of Workshops for the Baccalieu Trail Region. Over 50 people from communities across the Baccalieu Trail region -

Constitution (PDF)

Newfoundland & Labrador ftnglish School District Constitution AUGUST 311 2015 Constitution Legislative Authority and Reference 3 Article I: Name 4 Article II: Authority and Purpose 4 Article III: Boundaries 4 Article IV: Membership 4 7 Article V: Officers of the Board Committees of the Board 8 Article VI: Annual General Meeting 9 Article VII: Property 9 Article VIII: Amendments to Constitution 9 Article IX: Adoption of Constitution 10 Article X: Legislative Authority and Reference Whereas under Section 52 (1) of the Schools Act, 1997, the province shall be divided into school districts, as set by an order of the Lieutenant-Governor in Council; And Whereas a new school district,the Newfoundland and Labrador English School District, was established and school board trustees appointed, effective September 1, 2013, under the Boundaries of School Districts Order, 2013 NL Regulation 93/13 and Order in Council 2013-0252 respectively; And Whereas under Section 60(1) of the Schools Act, 1997, a school board is required, subject to the approval of the Minister of the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, to prescribe and adopt its constitution; and Now Therefore the School Board for the Newfoundland and Labrador English School District in a meeting duly assembled on October 20, 2014 hereby adopts and passes the following Constitution of the said Board. Newfoundland & Labrador English School District Constitution Page 3 Article I: Name 1. (a) The name of the Board shall be the “School Board for the Newfoundland and Labrador English School District” hereinafter referred to as “the Board”. (b) The name of the District administered by the Newfoundland and Labrador English School Board shall be the “Newfoundland and Labrador English School District”, hereinafter referred to as “the District”. -

Food Bank List

Food Bank List Bridges to Hope Campus Food Bank 39 Cookstown Road Corte Real, 57 Allandale Road 722-9225 Conception Bay South Food bank Corpus Christi Conference 81-3 Conception Bay Highway 260 Waterford Bridge Road 834-2800 364-4116 Emmaus House Northeast Avalon Food Bank Bonaventure Aveune 3 Thorne’s Lane, Torbay 753-6380 437-6367 Mary Queen of Peace Mary Queen of the World McDonald Drive Topsail Road 753-4014 364-7140 Salvation Army Salvation Army 21 Adam’s Avenue 106 Ashford Drive, Mt. Pearl 726-0393 364-6465 Single Parents Association St. Kevin’s Parish Food Bank 472 Logy Bay Road Main Road, Goulds 739-0709 745-2460 St. Paul’s Family Aid St. Peter’s Parish 340 Newfoundland Drive 110 Ashford Drive 754-1980 747-3320 St. Pius X Food Bank St. Theresa’s MacMorrin Centre 120 Mundy Pond Road 739-1329 579-7201 Bay of Islands Food Bank Network Baie D’Espoir Corner Brook 882-2442 634-2655 Botwood Interfaith Goodwill Caring by Sharing Botwood, NL Bell Island 257-3406 488-2656 Catalina Area Community Care & Share Communities Food Bank Catalina Bonavista & Area 469-2271 468-1686 Deer Lake Regional Food Bank Grand Bank/Fortune 18th Sixth Avenue Community Care Centre 635-2057 832-0606 Grand Falls/Windsor/Bishop Falls Green Bay Food Bank Grand Falls-Windsor Springdale 489-5810 673-3805 Helping Hand Food Bank Helping Hand Goodwill Centre Twillingate Bay Roberts 884-2366 786-9391 Holy Cross Parish Community Services Interfaith Goodwill Centre & 86 Salmonier Line Food Bank Holyrood Lewisporte 229-4898 535-8547 Labrador Friendship Centre Food Bank Labrador -

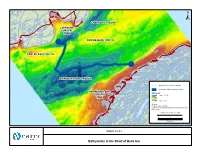

Bathymetry in the Strait of Belle Isle

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! L'Anse Amour ! -80 -60 ! Forteau -50 ! ± LABRADOR TROUGH LABRADOR COASTAL -100 ZONE -80 -80 -1 00 L'Anse-au-Clair ! CENTRE BANK NORTH -90 ! -50 CENTRE BANK SOUTH -40 -60 0 -100 Green Island Cove 5 -60 ! - -80 -90 ! Pines Cove ! -100 Shoal Cove ! Sandy Cove ! NEWFOUNDLAND TROUGH -10 -20 Savage Cove ! -9 0 -30 Bathymetry Lines (10 m interval) 00 -1 Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor - ! 1 0 0 0 NEWFOUNDLAND -1 0 Bathymetry * COASTAL High : 127.09 -2 Flower's Cove ZONE0 ! -70 Low : -0.16 Sources: * Fugro Jacques (2007) Location of troughs and banks from Woodworth-Lynas et al. (1992). -60 FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_406a ! 0 3 6 0 Kilometres -5 -80 ! ! FIGURE 10.5.2-2 ! Bathymetry in the Strait of Belle Isle ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! -

Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador

FEDERAL ELECTORAL BOUNDARIES COMMISSION FOR THE PROVINCE OF NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR PROPOSAL Part I – Introduction and Overview The Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador (the Commission) was established on February 21, 2012, pursuant to the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. E-3 (the Act). The Commission is composed of Julie Eveleigh, Member, Herbert Clarke, Deputy Chairperson, and the Honourable Keith Mercer, Chairperson. The Commission’s task is to consider and report on the readjustment of the boundaries of the electoral districts of the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador (the Province) as required upon completion of the 2011 decennial census. The 2011 decennial census established the population of the Province at 514,536. In accordance with subsection 14(1) of the Act, the Chief Electoral Officer has determined that the census and section 51 of the Constitution Act, 1867 dictate the representation of the Province in the House of Commons remaining at seven (7) members, therefore requiring seven electoral districts. The Act provides that the population of each electoral district shall correspond as closely as reasonably possible to the electoral quota for the province, which is determined by dividing the provincial population by the number of electoral districts. The electoral quota for the Province according to that calculation is 73,505. The Act further provides that the Commission may deviate from that quota having regard to the factors of community of interest