Annual Adult Survivorship of Loggerhead Shrikes in Southeastern Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maps of Land Cover and Soil Type in the Red Deer River Basin May, 2014

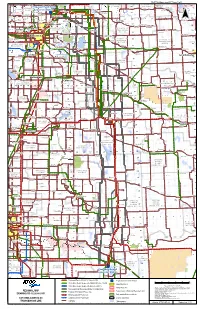

RED DEER RIVER BASIN FLOOD MITIGATION STUDY Appendix D – Maps of land cover and soil type in the Red Deer River Basin May, 2014 Appendix D – MAPS OF LAND COVER AND SOIL TYPE IN THE RED DEER RIVER BASIN nh \\cd1206-f09\shared_projects\113929356-rd_river_basin\07_reports_studies\rpt_red_deer_river_basin_mitigation_study_2014-05-21.docx D.1 County Of Wetaskiwin No. 10 «¯ 20 Bluffton 53 Rimbey Parkland Ponoka Camrose Bashaw Beach County County Leedale White Clive Tees 50 Mirror Sands 12 Bentley Alix Sunbreaker Blackfalds Withrow Cove Lacombe Nevis Eckville Half Joffre County Moon Bay Haynes Condor 11 Benalto Sylvan Lake Red Deer Ardley Delburne Red Deer County Of County 42 Lousana Stettler Penhold Markerville No. 6 21 Big Caroline 54 Spruce View Valley County Of Dickson Innisfail Byemoor Paintearth Elnora Endiang No. 18 Burnstick Dickson Lake Dam Bowden 56 Wimborne Rumsey 2 Trochu Sundre 27 Torrington Rowley Olds Three Craigmyle Mountain 9 Clearwater Alingham Hills Starland Hanna View County Morrin Richdale County County Delia Sunnyslope Didsbury Kneehill County Michichi Youngstown Linden Munson I.d. No. 9 22 Swalwell (banff Chinook Cereal N.p.) M.d. Of Cremona Carstairs Bighorn Acme Carbon Rocky View Hesketh No. 8 Water Oyen Valley County Drumheller Crossfield Wayne 40 Madden 10 Bottrel 72 Beiseker East Coulee Sunnynook 41 Irricana Dorothy Redland Acadia Valley M.d. Of Rockyford Acadia Kathyrn No. 34 Legend Dalroy 36 Empress Landcover Wetland Basin Boundary Calgary Strathmore Cessford Chestermere Water Herb Municipal Boundaries Bindloss 24 Wardlow Non-Vegetated Grassland Highways County Of d Newell x Wheatland 1 Cypress m Rock/Rubble Agriculture Red Deer River . -

2010 Final Receipt Point Rates: ($/103M3/Month, Except IT Which Is $/103M3/D) Effective from November 1, 2010

Summary of 2010 Final Receipt Point Rates: ($/103m3/month, except IT which is $/103m3/d) Effective from November 1, 2010 Average Receipt Price: 207.61 Receipt Price Floor: 121.71 Receipt Price Ceiling: 293.51 Point C Point B Point A Premium/Discount: 105% 100% 95% 110% 115% FT-RN PRICE 1 Year FT-R PRICE FT-R PRICE FT-R PRICE Non- Station Station 1 to < 3 3 to < 5 > 5 Renewable IT-R Project Number Station Name Mnemonic Year Term Year Term Year Term Firm PRICE Area 1001 BINDLOSS SOUTH BINDS 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 NE 1002 BINDLOSS N. #1 BINN1 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 NE 1003 PROVOST NORTH PROVN 192.21 183.06 173.91 201.37 6.92 NE 1004 CESSFORD WARDLO CEWRD 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 NE 1007 OYEN OYNXX 158.34 150.80 143.26 165.88 5.70 NE 1008 SIBBALD SIBBD 205.07 195.30 185.54 214.83 7.38 ML 1009 ATLEE-BUFFALO ATBUF 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 ML 1010 PRINCESS-DENHAR PRNDT 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 ML 1012 CESSFORD WEST CESFW 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 NE 1013 PROVOST SOUTH PROVS 209.54 199.56 189.58 219.52 7.55 NE 1015 COUNTESS MAKEPEACE CONTM 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 ML 1016 HUSSAR-CHANCELL HUCHA 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 ML 1017 MED HAT N. -

Specialized and Rural Municipalities and Their Communities

Specialized and Rural Municipalities and Their Communities Updated December 18, 2020 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] SPECIALIZED AND RURAL MUNICIPALITIES AND THEIR COMMUNITIES MUNICIPALITY COMMUNITIES COMMUNITY STATUS SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITES Crowsnest Pass, Municipality of None Jasper, Municipality of None Lac La Biche County Beaver Lake Hamlet Hylo Hamlet Lac La Biche Hamlet Plamondon Hamlet Venice Hamlet Mackenzie County HIGH LEVEL Town RAINBOW LAKE Town Fort Vermilion Hamlet La Crete Hamlet Zama City Hamlet Strathcona County Antler Lake Hamlet Ardrossan Hamlet Collingwood Cove Hamlet Half Moon Lake Hamlet Hastings Lake Hamlet Josephburg Hamlet North Cooking Lake Hamlet Sherwood Park Hamlet South Cooking Lake Hamlet Wood Buffalo, Regional Municipality of Anzac Hamlet Conklin Hamlet Fort Chipewyan Hamlet Fort MacKay Hamlet Fort McMurray Hamlet December 18, 2020 Page 1 of 25 Gregoire Lake Estates Hamlet Janvier South Hamlet Saprae Creek Hamlet December 18, 2020 Page 2 of 25 MUNICIPALITY COMMUNITIES COMMUNITY STATUS MUNICIPAL DISTRICTS Acadia No. 34, M.D. of Acadia Valley Hamlet Athabasca County ATHABASCA Town BOYLE Village BONDISS Summer Village ISLAND LAKE SOUTH Summer Village ISLAND LAKE Summer Village MEWATHA BEACH Summer Village SOUTH BAPTISTE Summer Village SUNSET BEACH Summer Village WEST BAPTISTE Summer Village WHISPERING HILLS Summer Village Atmore Hamlet Breynat Hamlet Caslan Hamlet Colinton Hamlet -

St2 St9 St1 St3 St2

! SUPP2-Attachment 07 Page 1 of 8 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! .! ! ! ! ! ! SM O K Y L A K E C O U N T Y O F ! Redwater ! Busby Legal 9L960/9L961 57 ! 57! LAMONT 57 Elk Point 57 ! COUNTY ST . P A U L Proposed! Heathfield ! ! Lindbergh ! Lafond .! 56 STURGEON! ! COUNTY N O . 1 9 .! ! .! Alcomdale ! ! Andrew ! Riverview ! Converter Station ! . ! COUNTY ! .! . ! Whitford Mearns 942L/943L ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 56 ! 56 Bon Accord ! Sandy .! Willingdon ! 29 ! ! ! ! .! Wostok ST Beach ! 56 ! ! ! ! .!Star St. Michael ! ! Morinville ! ! ! Gibbons ! ! ! ! ! Brosseau ! ! ! Bruderheim ! . Sunrise ! ! .! .! ! ! Heinsburg ! ! Duvernay ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! 18 3 Beach .! Riviere Qui .! ! ! 4 2 Cardiff ! 7 6 5 55 L ! .! 55 9 8 ! ! 11 Barre 7 ! 12 55 .! 27 25 2423 22 ! 15 14 13 9 ! 21 55 19 17 16 ! Tulliby¯ Lake ! ! ! .! .! 9 ! ! ! Hairy Hill ! Carbondale !! Pine Sands / !! ! 44 ! ! L ! ! ! 2 Lamont Krakow ! Two Hills ST ! ! Namao 4 ! .Fort! ! ! .! 9 ! ! .! 37 ! ! . ! Josephburg ! Calahoo ST ! Musidora ! ! .! 54 ! ! ! 2 ! ST Saskatchewan! Chipman Morecambe Myrnam ! 54 54 Villeneuve ! 54 .! .! ! .! 45 ! .! ! ! ! ! ! ST ! ! I.D. Beauvallon Derwent ! ! ! ! ! ! ! STRATHCONA ! ! !! .! C O U N T Y O F ! 15 Hilliard ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! N O . 1 3 St. Albert! ! ST !! Spruce ! ! ! ! ! !! !! COUNTY ! TW O HI L L S 53 ! 45 Dewberry ! ! Mundare ST ! (ELK ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! . ! ! Clandonald ! ! N O . 2 1 53 ! Grove !53! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ISLAND) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ardrossan -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

2017 Municipal Codes

2017 Municipal Codes Updated December 22, 2017 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] 2017 MUNICIPAL CHANGES STATUS CHANGES: 0315 - The Village of Thorsby became the Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017). NAME CHANGES: 0315- The Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017) from Village of Thorsby. AMALGAMATED: FORMATIONS: DISSOLVED: 0038 –The Village of Botha dissolved and became part of the County of Stettler (effective September 1, 2017). 0352 –The Village of Willingdon dissolved and became part of the County of Two Hills (effective September 1, 2017). CODE NUMBERS RESERVED: 4737 Capital Region Board 0522 Metis Settlements General Council 0524 R.M. of Brittania (Sask.) 0462 Townsite of Redwood Meadows 5284 Calgary Regional Partnership STATUS CODES: 01 Cities (18)* 15 Hamlet & Urban Services Areas (396) 09 Specialized Municipalities (5) 20 Services Commissions (71) 06 Municipal Districts (64) 25 First Nations (52) 02 Towns (108) 26 Indian Reserves (138) 03 Villages (87) 50 Local Government Associations (22) 04 Summer Villages (51) 60 Emergency Districts (12) 07 Improvement Districts (8) 98 Reserved Codes (5) 08 Special Areas (3) 11 Metis Settlements (8) * (Includes Lloydminster) December 22, 2017 Page 1 of 13 CITIES CODE CITIES CODE NO. NO. Airdrie 0003 Brooks 0043 Calgary 0046 Camrose 0048 Chestermere 0356 Cold Lake 0525 Edmonton 0098 Fort Saskatchewan 0117 Grande Prairie 0132 Lacombe 0194 Leduc 0200 Lethbridge 0203 Lloydminster* 0206 Medicine Hat 0217 Red Deer 0262 Spruce Grove 0291 St. Albert 0292 Wetaskiwin 0347 *Alberta only SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE NO. -

Communities Within Specialized and Rural Municipalities (May 2019)

Communities Within Specialized and Rural Municipalities Updated May 24, 2019 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] COMMUNITIES WITHIN SPECIALIZED AND RURAL MUNICIPAL BOUNDARIES COMMUNITY STATUS MUNICIPALITY Abee Hamlet Thorhild County Acadia Valley Hamlet Municipal District of Acadia No. 34 ACME Village Kneehill County Aetna Hamlet Cardston County ALBERTA BEACH Village Lac Ste. Anne County Alcomdale Hamlet Sturgeon County Alder Flats Hamlet County of Wetaskiwin No. 10 Aldersyde Hamlet Foothills County Alhambra Hamlet Clearwater County ALIX Village Lacombe County ALLIANCE Village Flagstaff County Altario Hamlet Special Areas Board AMISK Village Municipal District of Provost No. 52 ANDREW Village Lamont County Antler Lake Hamlet Strathcona County Anzac Hamlet Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo Ardley Hamlet Red Deer County Ardmore Hamlet Municipal District of Bonnyville No. 87 Ardrossan Hamlet Strathcona County ARGENTIA BEACH Summer Village County of Wetaskiwin No. 10 Armena Hamlet Camrose County ARROWWOOD Village Vulcan County Ashmont Hamlet County of St. Paul No. 19 ATHABASCA Town Athabasca County Atmore Hamlet Athabasca County Balzac Hamlet Rocky View County BANFF Town Improvement District No. 09 (Banff) BARNWELL Village Municipal District of Taber BARONS Village Lethbridge County BARRHEAD Town County of Barrhead No. 11 BASHAW Town Camrose County BASSANO Town County of Newell BAWLF Village Camrose County Beauvallon Hamlet County of Two Hills No. 21 Beaver Crossing Hamlet Municipal District of Bonnyville No. 87 Beaver Lake Hamlet Lac La Biche County Beaver Mines Hamlet Municipal District of Pincher Creek No. 9 Beaverdam Hamlet Municipal District of Bonnyville No. -

Cypress County

June 2014 Updated) Cypress County C-25.1 Cypress County Community Overview À EmpressÀ 561 Cessford À 899 Gem À 886 Bindloss À Wardlow 556 862 555À À 550 À Iddesleigh Rosemary 876 Jenner À Duchess À À Patricia 545 873 544 884À À 542À 542 à Hilda Brooks 41 À À 537 Lake 539 TilleyÀ À à Newell À 539 36 ResortÀ 876 1 Schuler 535 ¾ì A = 170 Rainier 873 À 875 528À Scandia À Rolling 530 Hills Suffield À À 525 526 À Medicine À Hays 524 Hat 524 Redcliff Veinerville Vauxhall À Desert À 523 Blume Irvine À Walsh 875 Dunmore 521 À Seven 864 à Persons Bow 3 Grassy À Purple Island Lake B = 79 515 à Springs Johnson'S 3 BurdettÀ Addition 879 Taber Barnwell À À À 514 À À 887 885 513 877 à 36 À à à 889 41 Wrentham 61 Skiff Etzikom à Orion Foremost 61 New Manyberries Dayton à À À À 4 À À À 885 889 879 887 506 877 À Warner 504 501À Milk À River À À 880 à 500 501 4 À 500À 500 Coutts Where subcommunities exist, letters (A, B, C, etc.) identify subcommunities; Legend numbers show the number of EDIs analyzed for each subcommunity. # of analyzed EDI 0 - 66 67 - 121 Please note: Percentages tend to be more representitive when 122 - 203 ! they are based on larger numbers. 204 - 350 351 - 900 ECMap June 2014 (Updated) Cypress County Additional Community Information EDI Summary: Number of EDIs available: 306 Number of EDIs used in analysis:249 % of special needs: 2.3% Age at EDI completion and gender Age Groups ≤ 5yrs 2mos 5yrs 3mos - 5yrs 6mos 5yrs 7mos - 5yrs 10mos > 5yrs 11mos Total Gender N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) F 23 (9.2%) 45 (18.1%) 41 (16.5%) 14 (5.6%) 123 (49.4%) M 18 (7.2%) 32 (12.9%) 44 (17.7%) 32 (12.9%) 126 (50.6%) FM 41 (16.5%) 77 (30.9%) 85 (34.1%) 46 (18.5%) 249 (100%) * Please note: The total number of boys and girls in each category may not add up to an exact total because gender may not have been identifed in all questionnaires. -

Legend - AUPE Area Councils Whiskey Gap Del Bonita Coutts

Indian Cabins Steen River Peace Point Meander River 35 Carlson Landing Sweet Grass Landing Habay Fort Chipewyan 58 Quatre Fourches High Level Rocky Lane Rainbow Lake Fox Lake Embarras Portage #1 North Vermilion Settlemen Little Red River Jackfish Fort Vermilion Vermilion Chutes Fitzgerald Embarras Paddle Prairie Hay Camp Carcajou Bitumount 35 Garden Creek Little Fishery Fort Mackay Fifth Meridian Hotchkiss Mildred Lake Notikewin Chipewyan Lake Manning North Star Chipewyan Lake Deadwood Fort McMurray Peerless Lake #16 Clear Prairie Dixonville Loon Lake Red Earth Creek Trout Lake #2 Anzac Royce Hines Creek Peace River Cherry Point Grimshaw Gage 2 58 Brownvale Harmon Valley Highland Park 49 Reno Blueberry Mountain Springburn Atikameg Wabasca-desmarais Bonanza Fairview Jean Cote Gordondale Gift Lake Bay Tree #3 Tangent Rycroft Wanham Eaglesham Girouxville Spirit River Mclennan Prestville Watino Donnelly Silverwood Conklin Kathleen Woking Guy Kenzie Demmitt Valhalla Centre Webster 2A Triangle High Prairie #4 63 Canyon Creek 2 La Glace Sexsmith Enilda Joussard Lymburn Hythe 2 Faust Albright Clairmont 49 Slave Lake #7 Calling Lake Beaverlodge 43 Saulteaux Spurfield Wandering River Bezanson Debolt Wembley Crooked Creek Sunset House 2 Smith Breynat Hondo Amesbury Elmworth Grande Calais Ranch 33 Prairie Valleyview #5 Chisholm 2 #10 #11 Grassland Plamondon 43 Athabasca Atmore 55 #6 Little Smoky Lac La Biche Swan Hills Flatbush Hylo #12 Colinton Boyle Fawcett Meanook Cold Rich Lake Regional Ofces Jarvie Perryvale 33 2 36 Lake Fox Creek 32 Grand Centre Rochester 63 Fort Assiniboine Dapp Peace River Two Creeks Tawatinaw St. Lina Ardmore #9 Pibroch Nestow Abee Mallaig Glendon Windfall Tiger Lily Thorhild Whitecourt #8 Clyde Spedden Grande Prairie Westlock Waskatenau Bellis Vilna Bonnyville #13 Barrhead Ashmont St. -

Archaeological

flALBERTA 1 (ArchaeologicaNo. 37 ISSN 0701-1176 Fall 2002 l Contents 2 Provincial Society Officers, Features 2002-2003 11 A Miraculous Medal from Rocky 3 Editor's Note Mountain House National Historic 3 Past Editor's Report Site, Alberta 4 2002 Annual General Meeting 15 January Cave: An Ancient Window 6 Centre Reports on the Past 10 Diane Lyons Appointment 17 Alberta Graduate Degrees in 20 Recent Abstracts Archaeology, Part 1 36 Wahkpa Chu'gn Buffalo Jump Grand 21 Archaeological Survey of Alberta Opening Issued Permits, December 2001 - 36 In Memory October 2002 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF ALBERTA Charter #8205, registered under the Societies Act of Alberta on February 7, 1975 PROVINCIAL SOCIETY OFFICERS 2002-2003 President Marshall Dzurko RED DEER CENTRE. 147 Woodfern Place SW President: Shawn Haley Calgary AB T2W4R7 R.R. 1 Phone:403-251-0694 Bowden.AB TOM 0K0 Email: [email protected] Phone: 403-224-2992 Email: [email protected] Past-President Neil Mirau 2315 20* Street SOUTH EASTERN ALBERTA CoaldaleAB TIM 1G5 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY: Phone: 403-345-3645 President: Lorine Marshall 97 First Street NE Executive Secretary/ Jim McMurchy Medicine Hat AB T1A 5J9 Treasurer 97 Eton Road West Phone: 403-527-2774 Lethbridge AB T1K4T9 Email: [email protected] Phone:403-381-2655 Email: [email protected] STRATHCONA CENTRE: President: Kristine Wright-Fedynyak Alberta Archaeological Dr. John Dormaar Provincial Museum of Alberta Review Editor Research Centre 12845 102 Ave Agr. & Agri-Food Canada Edmonton AB T5N 0M6 PO Box 3000 Provincial Rep: George Chalut Lethbridge AB T1J4B1 Email: [email protected] Alberta Archaeological Carol Mcreary Review Distribution Box 611 Black Diamond AB T0L0H0 Alberta Archaeological Review Phone:403-933-5155 Editor: John Dormaar ([email protected]) Email: [email protected] Layout & Design: Larry Steinbrenner ([email protected]) Distribution: Carol Mccreary ([email protected]) REGIONAL CENTRES AND MEMBER SOCIETIES Members of the Archaeological Society of Alberta receive a copy of the Alberta Archaeological Review. -

Jim & Dolores Purves April 29, 2020

Unreserved Public Real Estate Auction Jim & Dolores Purves 1 Parcel of Real Estate – 79.89±Title Acres Will be sold to the highest bidder 2015 Built 4324± Sq Ft Shop & Living Quarters April 29, 2020 $8655 Surface Lease Revenue – Brooks, AB Edmonton Auction Site AB/County of Newell Parcel 1 – Lot 1, Blk 1, Plan 0812922 – 79.89± Title Acres – Home Parcel ▸ 2015 50 ft x 60 ft shop w/2000± sq ft living quarters on two levels. (2) bedroom, (3) bathroom, 2000± sq ft of shop space, (2) 14 ft x 14 ft OH doors, attached 18 ft x 18 ft sunroom, underfloor 41,000 gallon water cistern, detached 14 ft x 34 ft cold storage garage, 70± ac native pasture, balance yard site and oil & gas leases, fenced, livestock corrals, livestock water, 40 ft sea container livestock feeder, RV parking w/water & power, municipal water, septic holding tank, power, on propane (rented tank), security gate, security system, surface lease revenue $8655. Zoned “FR” Fringe, taxes $1834.24. Property is conveniently located within 20 km Sunroom of Lake Newell and Rolling Hills Lake for boating, swimming and fishing. Shop w/Living Quarters ▸ 2015 built 50 ft x 60 ft w/18 ft x 18 ft attached sunroom ▸ 2 x 6 construction, metal clad, metal roof ▸ 41,000± gallon underfloor water cistern ▸ 300-gallon poly water cistern, pressure system ▸ Forced air furnace & forced air overhead heater ▸ 20 ft x 65 ft concrete apron Living Quarters Kitchen ▸ 2000± sq ft developed living space on two floors ▸ 9 ft main floor ceiling height ▸ 2 bedrooms Open House Dates: · 1 main floor, 1 upstairs April 5 & 19 – 2 to 4 pm ▸ 2 bathrooms · 1 main floor, 1 upstairs For more information: ▸ Laminate tile flooring Jim Purves – Contact Kitchen 403.529.7770 ▸ Built-in stainless-steel microwave Jerry Hodge – Ritchie Bros. -

Assessment of the Distribution and Relative Abundance of Sport Fish in the Lower Red Deer River (Phase I)

Assessment of the Distribution and Relative Abundance of Sport Fish in the Lower Red Deer River (Phase I) CCONSERVATIONO NSE R VAT IO N RREPORTE P O R T SSERIESE R IE S CCONSERVATIONONSERVATION RREPORTEPORT SSERIESERIES 25% Post Consumer Fibre When separated, both the binding and paper in this document are recyclable Assessment of the Distribution and Relative Abundance of Sport Fish in the Lower Red Deer River (Phase I) Jason Cooper and Trevor Council Alberta Conservation Association 2nd Floor, YPM Place 530-8 Street S. Lethbridge, Alberta T1J 2J8 Report Series Co-editors GARRY J. SCRIMGEOUR STEPHANIE R. GROSSMAN Alberta Conservation Association Alberta Conservation Association P.O. Box 40027 P.O. Box 40027 Baker Centre Postal Outlet Baker Centre Postal Outlet Edmonton, AB, T5J 4M9 Edmonton, AB, T5J 4M9 Conservation Report Series Types: Interim, Activity, Data, Technical ISBN printed: 0-7785-3660-2 ISBN online: 0-7785-3661-0 ISSN printed: 1712-2821 ISSN online: 1712-283X Publication Number: I/202 Disclaimer: This document is an independent report prepared by the Alberta Conservation Association. The authors are solely responsible for the interpretations of data and statements made within this report. Reproduction and Availability: This report and its contents may be reproduced in whole, or in part, provided that this title page is included with such reproduction and/or appropriate acknowledgements are provided to the authors and sponsors of this project. Suggested citation: Cooper, J. and T. Council. 2004. Assessment of the distribution and relative abundance of sport fish in the lower Red Deer River (Phase I). Data report (D-2004-004) produced by Alberta Conservation Association, Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada.