'To Me, He's a No-Brainer, High-Lottery Pick': Scottie Barnes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-19 ACC Basketball

2018-19 ACC Basketball ACC Standings As of Saturday, December 22, 2018 ACColades ACC Games Overall Ten non-conference games on tap for Satur- Team W L Pct. Hm Rd W L Pct. Hm Rd Nu Streak day ... Louisville tops Robert Morris 73-59 in Virginia 0 0 .000 0-0 0-0 10 0 1.000 5-0 2-0 3-0 Won 10 lone Friday action ... with Duke’s 69-58 win Duke 0 0 .000 0-0 0-0 11 1 .917 7-0 0-0 4-1 Won 6 over No. 12 Texas Tech Thursday, the ACC Florida State 0 0 .000 0-0 0-0 10 1 .909 6-0 1-0 3-1 Won 5 improves to 13-9 against non-league ranked NC State 0 0 .000 0-0 0-0 10 1 .909 8-0 0-1 2-0 Won 4 opponents, including five wins against teams Virginia Tech 0 0 .000 0-0 0-0 10 1 .909 6-0 0-1 4-0 Won 5 in the top ten of the AP poll ... eight different ACC teams have at least one win against a Boston College 0 0 .000 0-0 0-0 8 2 .800 6-2 0-0 2-0 Won 2 ranked opponent this season ... Virginia’s North Carolina 0 0 .000 0-0 0-0 8 2 .800 5-0 2-1 1-1 Won 2 17-point win at South Carolina Wednesday Louisville 0 0 .000 0-0 0-0 9 3 .750 8-0 1-1 0-2 Won 3 extends the Cavaliers’ road game win streak Notre Dame 0 0 .000 0-0 0-0 9 3 .750 8-1 0-1 1-1 Won 3 to 11 in a row, tying for the seventh longest Pittsburgh 0 0 .000 0-0 0-0 9 3 .750 7-1 0-2 2-0 Won 2 in league history .. -

Oklahoma State's Cade Cunningham Is the Recipient

www.KyleMacyAward.com April 1, 2021 OKLAHOMA STATE’S CADE CUNNINGHAM IS THE RECIPIENT OF THE 2021 KYLE MACY NATIONAL FRESHMAN OF THE YEAR AWARD BOSTON, MA -- Oklahoma State’s Cade Cunningham is the recipient of the 2021 Kyle Macy award. The 6-foot-8 native of Arlington, TX led the Big 12 in scoring, averaging 20.1 points per game, which included a season-best 40 points in a win over No. 7 ranked Oklahoma on Feb. 27. He also averaged 6.2 rebounds and 3.5 assists per contest and was a nine-time recipient of the Big 12 Player/Newcomer of the Week honor, which was the most by any player this season and the most in school history. “Cade Cunningham is easily one of the top three or four players in college basketball and nobody would argue if you said he is the best,” said Angela Lento Vice President of CollegeInsider.com. “The only thing disappointing about his game is that we won’t see it, at the college level, for more than one season.” Cunningham’s sensational season included several prominent honors including First Team All-America honors from the Associated Press, USA Today, the Sporting News and the United States Basketball Writers Association. He is also a finalist for the Naismith Trophy and the Bob Cousy Point Guard of the Year awards. The Kyle Macy Award, which is presented annually to the top freshman in Division I college basketball, is named for a guard who starred as a freshman for Purdue. The 1975 Indiana "Mr. -

Nsu University School Student-Athlete Named Gatorade® Florida Boys Basketball Player of the Year

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Kisa Mugwanya (312-729- 3670) [email protected] NSU UNIVERSITY SCHOOL STUDENT-ATHLETE NAMED GATORADE® FLORIDA BOYS BASKETBALL PLAYER OF THE YEAR CHICAGO (March 15, 2019) — In its 34th year of honoring the nation’s best high school athletes, The Gatorade Company today announced Vernon Carey Jr. of NSU University School as its 2018-19 Gatorade Florida Boys Basketball Player of the Year. Carey Jr. is the first Gatorade Florida Boys Basketball Player of the Year to be chosen from NSU University School. The award, which recognizes not only outstanding athletic excellence, but also high standards of academic achievement and exemplary character demonstrated on and off the field, distinguishes Carey Jr. as Florida’s best high school boys basketball player. Now a finalist for the prestigious Gatorade National Boys Basketball Player of the Year award to be announced in March, Carey Jr. joins an elite alumni association of past state boys basketball award winners, including Karl-Anthony Towns (2012-13 & 2013-14, St. Joseph High School, N.J.), Dwight Howard (2003-04, Southwest Atlanta Christian Academy, Ga.), Chris Bosh (2001-02, Lincoln High School, Texas), Paul Pierce (1994-95, Inglewood High School, Calif.), Chauncey Billups (1993-94 & 1994-95, George Washington High School, Colo.) and Jason Kidd (1991-92, St. Joseph Notre Dame High School, Calif.). The 6-foot-10, 255-pound senior center led the Sharks to a 27-4 record and a second straight Class 5A state championship this past season. Carey averaged 21.1 points, 9.0 rebounds, 1.5 assists and 1.1 blocks per game. -

Set Info - Player - 2019-20 Contenders Optic Basketball

Set Info - Player - 2019-20 Contenders Optic Basketball Set Info - Player - 2019-20 Contenders Optic Basketball Player Total # Cards Total # Base Total # Autos Total # Memorabilia Total # Autos + Memorabilia Ja Morant 767 55 712 0 0 RJ Barrett 767 55 712 0 0 Kendrick Nunn 734 22 712 0 0 Jarrett Culver 723 11 712 0 0 Grant Williams 712 0 712 0 0 Talen Horton-Tucker 712 0 712 0 0 Keldon Johnson 712 0 712 0 0 Nassir Little 712 0 712 0 0 Kyle Guy 712 0 712 0 0 Nicolo Melli 712 0 712 0 0 Bruno Fernando 712 0 712 0 0 Isaiah Roby 712 0 712 0 0 Goga Bitadze 712 0 712 0 0 Kevin Porter Jr. 712 0 712 0 0 Nicolas Claxton 712 0 712 0 0 Rui Hachimura 620 44 576 0 0 Tyler Herro 587 11 576 0 0 Cam Reddish 587 11 576 0 0 Jaxson Hayes 587 11 576 0 0 Luka Samanic 576 0 576 0 0 Admiral Schofeld 576 0 576 0 0 Ty Jerome 576 0 576 0 0 Bol Bol 576 0 576 0 0 Carsen Edwards 576 0 576 0 0 Jaylen Nowell 576 0 576 0 0 Mfondu Kabengele 576 0 576 0 0 Dylan Windler 576 0 576 0 0 Sekou Doumbouya 564 0 564 0 0 Cameron Johnson 523 11 512 0 0 Matisse Thybulle 512 0 512 0 0 Nickeil Alexander-Walker 512 0 512 0 0 PJ Washington Jr. 475 11 464 0 0 Giannis Antetokounmpo 401 326 75 0 0 Anthony Davis 401 326 75 0 0 Coby White 395 11 384 0 0 Stephen Curry 379 304 75 0 0 Brandon Clarke 376 0 376 0 0 Cody Martin 376 0 376 0 0 Pascal Siakam 365 229 136 0 0 Trae Young 362 229 133 0 0 Zion Williamson 349 55 294 0 0 Damian Lillard 346 271 75 0 0 Kevin Durant 346 271 75 0 0 Eric Paschall 328 0 328 0 0 Shai Gilgeous-Alexander 321 185 136 0 0 D`Angelo Russell 310 174 136 0 0 Buddy Hield 299 163 136 0 0 Andrew Wiggins 299 163 136 0 0 Markelle Fultz 299 163 136 0 0 Bogdan Bogdanovic 299 163 136 0 0 Jaren Jackson Jr. -

13 JOEY BAKER Fayetteville, N.C

Fr. | Forward | 6-7 | 200 13 JOEY BAKER Fayetteville, N.C. | Trinity Christian School » CAREER HIGHS » PRODUCTION TRACKER Points 3 vs. North Dakota State 3/22/19 2018-19 CAREER Rebounds 2 2x, last vs. North Dakota State 3/22//19 Double-figure points Assists 20-pt games Steals 3+ 3pt FG FG Made 1 vs. North Dakota State 3/22/19 5+ assists 3FG Made 1 vs. North Dakota State 3/22/19 Dunks FT Made Three-point plays Minutes 7 vs. North Dakota State 3/22/19 Four-point plays » 2018-19 GAME-BY-GAME STATS » NOTABLES OPPONENT FG PCT. 3FG PCT. FT PCT. O-D-T PF PTS A TO BLK STL MIN BAKER RECLASSIFIES TO JOIN DUKE vs. [2] Kentucky dnp (coach’s decision) » Baker was four-star recruit who was ranked as the No. Army West Point dnp (coach’s decision) 41 overall prospect and No. 3 player in the state of North Eastern Michigan dnp (coach’s decision) Carolina in the class of 2018 by ESPN. vs. San Diego State dnp (coach’s decision) » He had committed to Duke for the 2019 class, but reclassified this past summer. vs. [8] Auburn dnp (coach’s decision) vs. [3] Gonzaga dnp (coach’s decision) FIRST DUKE MINUTES Indiana dnp (coach’s decision) » Baker saw his first action as a Blue Devil in the Feb. 23rd Stetson dnp (coach’s decision) win at Syracuse, coming off the bench for five minutes Hartford dnp (coach’s decision) and grabbing two rebounds. Yale dnp (coach’s decision) » He was Duke’s first substitution of the game, along with Princeton dnp (coach’s decision) Antonio Vrankovic. -

2019-20 Contenders Optic Basketball Checklist

2019-20 Contenders Optic Basketball Checklist - Hobby - NBA Rookie Ticket Auto = Yellow; Insert Autograph = Orange Player Set Card # Team Print Run Matisse Thybulle Auto - Rookie Season Ticket + Parallels/Variations 129 76ers Al Horford Auto - NBA Ink + Parallels 6 76ers 136 Allen Iverson Auto - 1982 Tribute + Parallels 2 76ers Allen Iverson Auto - Veteran Ticket + Parallels 1 76ers Matisse Thybulle Auto - Up and Coming + Parallels 19 76ers 136 Al Horford Base - Season Ticket 18 76ers Allen Iverson Insert - All-Star Aspirations 3 76ers Allen Iverson Insert - Historic Picks Dual Player 14 76ers Andre Iguodala Insert - Historic Slams 12 76ers Ben Simmons Base - Season Ticket 62 76ers Ben Simmons Insert - Front Row Seat 12 76ers Ben Simmons Insert - Playing the Numbers Game 25 76ers Ben Simmons Insert - Uniformity 19 76ers Charles Barkley Insert - All-Star Aspirations 4 76ers Charles Barkley Insert - Historic Picks Dual Player 5 76ers Joel Embiid Base - Season Ticket 51 76ers Joel Embiid Insert - All-Star Aspirations 13 76ers Joel Embiid Insert - Front Row Seat 13 76ers Joel Embiid Insert - Superstars 10 76ers Joel Embiid Insert - Uniformity 29 76ers Tobias Harris Base - Season Ticket 11 76ers GroupBreakChecklists.com 2019-20 Contenders Optic Basketball Checklist - Hobby - NBA Player Set Card # Team Print Run Nassir Little Auto - Rookie Season Ticket + Parallels/Variations 101 Blazers Anfernee Simons Auto - Sophomore Contenders + Parallels 8 Blazers 136 Damian Lillard Auto - 1982 Tribute + Parallels 1 Blazers Damian Lillard Auto - Veteran -

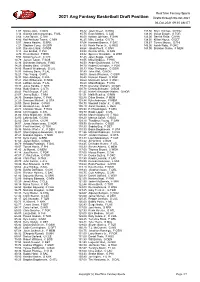

2020 Avg Fantasy Basketball Draft Position

RealTime Fantasy Sports 2021 Avg Fantasy Basketball Draft Position Drafts through 03-Oct-2021 04-Oct-2021 09:35 AM ET 1.07 Nikola Jokic, C DEN 85.42 Jalen Green, G HOU 137.50 Khyri Thomas, G HOU 3.14 Giannis Antetokounmpo, F MIL 85.75 Evan Mobley, C CLE 138.00 Goran Dragic, G TOR 3.64 Luka Doncic, G DAL 86.00 Keldon Johnson, F SAN 138.00 Derrick Rose, G NYK 4.86 Karl-Anthony Towns, C MIN 86.25 Mike Conley, G UTA 138.50 Killian Hayes, G DET 5.57 James Harden, G BRK 87.64 Harrison Barnes, F SAC 139.67 Tyrese Maxey, G PHI 7.21 Stephen Curry, G GSW 87.83 Kevin Porter Jr., G HOU 143.00 Isaiah Roby, F OKC 8.93 Damian Lillard, G POR 88.64 Jakob Poeltl, C SAN 143.00 Brandon Clarke, F MEM 9.14 Joel Embiid, C PHI 89.58 Derrick White, G SAN 9.79 Kevin Durant, F BRK 89.82 Spencer Dinwiddie, G WSH 9.93 Nikola Vucevic, C CHI 92.45 Jalen Suggs, G ORL 10.79 Jayson Tatum, F BOS 93.55 Mikal Bridges, F PHX 12.36 Domantas Sabonis, F IND 94.50 Andre Drummond, C PHI 14.29 Bradley Beal, G WSH 94.70 Robert Covington, F POR 14.86 Russell Westbrook, G LAL 95.33 Klay Thompson, G GSW 14.93 Anthony Davis, F LAL 97.89 John Wall, G HOU 16.21 Trae Young, G ATL 98.00 James Wiseman, C GSW 16.93 Bam Adebayo, F MIA 98.40 Norman Powell, G POR 17.21 Zion Williamson, F NOR 98.60 Montrezl Harrell, F WSH 19.43 LeBron James, F LAL 98.60 Miles Bridges, F CHA 19.43 Julius Randle, F NYK 99.40 Devonte' Graham, G NOR 19.64 Rudy Gobert, C UTA 100.78 Dennis Schroder, G BOS 20.43 Paul George, F LAC 101.45 Nickeil Alexander-Walker, G NOR 23.07 Jimmy Butler, F MIA 101.91 Malik Beasley, -

KNICKS (41-31) Vs

2020-21 SCHEDULE 2021 NBA PLAYOFFS ROUND 1; GAME 5 DATE OPPONENT TIME/RESULT RECORD Dec. 23 @. Indiana L, 121-107 0-1 Dec. 26 vs. Philadelphia L, 109-89 0-2 #4 NEW YORK KNICKS (41-31) vs. #5 ATLANTA HAWKS (41-31) Dec. 27 vs. Milwaukee W, 130-110 1-2 Dec. 29 @ Cleveland W, 95-86 2-2 (SERIES 1-3) Dec. 31 @ TB Raptors L, 100-83 2-3 Jan. 2 @ Indiana W, 106-102 3-3 Jan. 4 @ Atlanta W, 113-108 4-3 JUNE 2, 2021 *7:30 P.M Jan. 6 vs. Utah W, 112-100 5-3 Jan. 8 vs. Oklahoma City L, 101-89 5-4 MADISON SQUARE GARDEN (NEW YORK, NY) Jan. 10 vs. Denver L, 114-89 5-5 Jan. 11 @ Charlotte L, 109-88 5-6 TV: ESPN, MSG; RADIO: 98.7 ESPN Jan. 13 vs. Brooklyn L, 116-109 5-7 Jan. 15 @ Cleveland L, 106-103 5-8 Knicks News & Updates: @NY_KnicksPR Jan. 17 @ Boston W, 105-75 6-8 Jan. 18 vs. Orlando W, 91-84 7-8 Jan. 21 @ Golden State W, 119-104 8-8 Jan. 22 @ Sacramento L, 103-94 8-9 Jan. 24 @ Portland L, 116-113 8-10 Jan. 26 @ Utah L, 108-94 8-11 Jan. 29 vs. Cleveland W, 102-81 9-11 Jan. 31 vs. LA Clippers L, 129-115 9-12 Name Number Pos Ht Wt Feb. 1 @ Chicago L, 110-102 9-13 Feb. 3 @ Chicago W, 107-103 10-13 Feb. 6 vs. Portland W, 110-99 11-13 DERRICK ROSE (Playoffs) 4 G 6-3 200 Feb. -

Stats » Notables

Fr. | Forward | 6-7 | 200 13 JOEY BAKER Fayetteville, N.C. | Trinity Christian School » CAREER HIGHS » PRODUCTION TRACKER Points 3 vs. North Dakota State 3/22/19 2018-19 CAREER Rebounds 2 2x, last vs. North Dakota State 3/22//19 Double-figure points Assists 20-pt games Steals 3+ 3pt FG FG Made 1 vs. North Dakota State 3/22/19 5+ assists 3FG Made 1 vs. North Dakota State 3/22/19 Dunks FT Made Three-point plays Minutes 7 vs. North Dakota State 3/22/19 Four-point plays » 2018-19 GAME-BY-GAME STATS » NOTABLES OPPONENT FG PCT. 3FG PCT. FT PCT. O-D-T PF PTS A TO BLK STL MIN BAKER RECLASSIFIES TO JOIN DUKE vs. [2] Kentucky dnp (coach’s decision) » Baker was four-star recruit who was ranked as the No. Army West Point dnp (coach’s decision) 41 overall prospect and No. 3 player in the state of North Eastern Michigan dnp (coach’s decision) Carolina in the class of 2018 by ESPN. vs. San Diego State dnp (coach’s decision) » He had committed to Duke for the 2019 class, but reclassified this past summer. vs. [8] Auburn dnp (coach’s decision) vs. [3] Gonzaga dnp (coach’s decision) FIRST DUKE MINUTES Indiana dnp (coach’s decision) » Baker saw his first action as a Blue Devil in the Feb. 23rd Stetson dnp (coach’s decision) win at Syracuse, coming off the bench for five minutes Hartford dnp (coach’s decision) and grabbing two rebounds. Yale dnp (coach’s decision) » He was Duke’s first substitution of the game, along with Princeton dnp (coach’s decision) Antonio Vrankovic. -

(Pdf) Download

NHL PACIFIC FACES Oilers, Sabres sagging North Korea said Villains in ‘Gotham’ despite star power of to be rebuilding take spotlight in final McDavid, Eichel rocket launch site episodes of season Back page Page 5 Page 17 Illnesses mount from contaminated water on military bases » Page 6 stripes.com Volume 77, No. 230 ©SS 2019 THURSDAY, MARCH 7, 2019 50¢/Free to Deployed Areas Final flights Service of Marine Corps’ Prowler comes to a close with deactivation of last squadron Page 6 LIAM D. HIGGINS/Courtesy of the U.S. Marine Corps Two U.S. Marine Corps EA-6B Prowlers fly off the coast of North Carolina on Feb. 28, prior to their deactivation on Thursday. Afghan official: Suicide blast near airport in east kills 17 BY RAHIM FAIEZ U.S. forces to assist the Afghan troops in the State are active in eastern Afghanistan, espe- The dawn assault Associated Press shootout. cially in Nangarhar. Among those killed were 16 employees of The two groups have been carrying out triggered an KABUL, Afghanistan — Militants in Af- the Afghan construction company EBE and a near-daily attacks across Afghanistan in re- hourslong gunbattle ghanistan set off a suicide blast Wednesday military intelligence officer, said Attahullah cent years, mainly targeting the government with local guards, morning and stormed a construction company Khogyani, the provincial governor’s spokes- and Afghan security forces and causing stag- near the airport in Jalalabad, the capital of man. He added that nine other people were gering casualties, including among civilians. drawing in U.S. eastern Nangarhar province, killing at least 17 wounded in the attack, which lasted more than The attacks have continued despite stepped-up forces to assist the U.S. -

March 31 - April 2, 2016 New York City

MARCH 31 - APRIL 2, 2016 NEW YORK CITY PRESENTED BY: FOR MORE INFORMATION AND TO PURCHASE TICKETS VISIT WWW.DICKSNATIONALS.COM 10 @DICKSNATIONALS FACEBOOK.COM/DICKSNATIONALS TABLE OF CONTENTS Dear Basketball Fans: We are excited to be the title sponsor of the third- annual DICK’S High School Nationals in New York USA TODAY SUPER 25 BOYS NATIONAL RANKINGS 3 City. At DICK’S Sporting Goods, we feel strongly BOYS BRACKET 4 that sports play a vital role in teaching young people fundamental values such as a strong work ethic, MONTVERDE ACADEMY 5 teamwork and good sportsmanship. We also believe that supporting events that fulfill the dreams of young OAK HILL ACADEMY 6 athletes are a great way to promote those values. As FINDLAY PREP 7 a Company, we embrace the idea that sports make people better and are a powerful influence in the lives ST. BENEDICT’S PREP 9 of many. LA LUMIERE 10 This year we brought top-tier, nationally ranked MILLER GROVE 11 boys and girls high school basketball teams to New WASATCH ACADMEY 12 York City to compete in a tournament and crown a champion. We are thrilled to bring this level of talent PROVIDENCE DAY SCHOOL 13 to a national stage as we celebrate excellent team- ESPN BOYS PLAYER RANKINGS 14-15 play in the heart of NYC, and ultimately, in the world’s most famous arena. USA TODAY SUPER 25 GIRLS NATIONAL RANKINGS 16 GIRLS BRACKET 17 We look forward to enjoying a great basketball tournament with you. Thank you for your support of RIVERDALE BAPTIST 18 this great event and these talented athletes. -

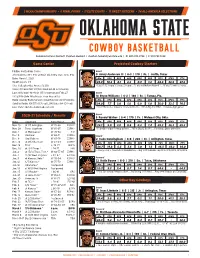

Game Center 2020-21 Schedule / Results Projected Cowboy Starters

2 NCAA CHAMPIONSHIPS • 6 FINAL FOURS • 11 ELITE EIGHTS • 11 SWEET SIXTEENS • 34 ALL-AMERICA SELECTIONS Communications Contact: Stephen Howard I [email protected] | O: 405.744.7756 | C: 817.793.5199 Game Center Projected Cowboy Starters Phillips 66 Bedlam Series Guard 7/8 Oklahoma (14-7, 9-6) at RV/21 Oklahoma State (16-6, 9-6) 0 Avery Anderson III | 6-3 | 170 | Fr. | Justin, Texas Date: March 1, 2021 Min. PPG RPG APG BPG SPG FG% 3FG% FT% Tipoff: 8 p.m. CT 29.9 10.2 4.1 2.2 0.3 1.2 44.5 32.5 87.8 Site: Gallagher-Iba Arena (13,611) • Last 6: 12.7 ppg, 5.5 rpg, 2.8 apg ... 15 pts in Bedlam Round 1 ... 16 pts/10 reb vs Texas. Series: OU leads 140-101 (OSU leads 64-46 in Stillwater) Last: OSU won 94-90 in OT in Norman on Feb. 27 Guard TV: ESPN (Bob Wischusen, Fran Fraschilla) 14 Bryce Williams | 6-2 | 180 | Sr. | Tampa, Fla. Radio: Cowboy Radio Network (Dave Hunziker, John Holcomb) Min. PPG RPG APG BPG SPG FG% 3FG% FT% Satellite Radio: XM 375 (OSU call), XM/Sirius 84 (OU call) 24.0 7.7 2.0 1.8 0.9 1.0 36.0 32.5 74.5 Live Stats: okstate.statbroadcast.com • Most BPG by 6-2 player or shorter in NCAA ... 13th in Big 12 in BPG ... 9 double-digit games. 2020-21 Schedule / Results Guard 5 Rondel Walker | 6-4 | 170 | Fr. | Midwest City, Okla. Date Opponent Time/Result TV Min.