Euro Zone Debt Crisis: Theory of Optimal Currency Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theory of Optimum Currency Areas and Business Cycle Synchronization in Central and Eastern European Countries

TALLINN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Tallinn School of Economics and Business Administration Department of Finance and Economics Chair of Finance and Banking Natalia Levenko THE THEORY OF OPTIMUM CURRENCY AREAS AND BUSINESS CYCLE SYNCHRONIZATION IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES Master’s thesis Supervisor: Professor Karsten Staehr Tallinn 2014 I declare I have written the master’s thesis independently. All works and major viewpoints of the other authors, data from other sources of literature and elsewhere used for writing this paper have been referenced. Natalia Levenko …………………………… (signature, date) Student’s code: 122351 Student’s e-mail address: [email protected] Supervisor: Professor Karsten Staehr The paper conforms to the requirements set for the master’s thesis …………………………………………… (signature, date) Chairman of defence committee: Permitted to defence …………………………………………… (title, name, signature, date) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 5 2. THEORETICAL STUDIES ................................................................................................... 8 2.1. The theory of the optimum currency areas ........................................................................ 8 2.1.1. The original theory ................................................................................................... -

Optimum Currency Areas and European Monetary Integration: Evidence from the Italian and German Unifications

Optimum Currency Areas and European Monetary Integration: Evidence from the Italian and German Unifications Roger Vicquery´ * London School of Economics November 2017 Abstract Recent events have sparked renewed research interest in international monetary integration and currency areas. This paper provides new empirical evidence on the predictive power and endogeneity of the Optimum Currency Areas (OCA) framework, by analyzing the wave of European monetary integration occuring between 1852 and the establishment of the international gold standard. This period witnessed to the creation of two national monetary unions lasting to this day, Italy and Germany, as well as monetary integration around Britain and France. I estimate the ex-ante optimality of various monetary arrangements, relying on a newly collected dataset allowing to proxy the assymetry of shocks across European regions. My findings support the predictive power of the OCA framework. In particular, I find that, opposite to Germany, Italian pre-unitary states did not form an OCA at unification. I argue that this might have contributed to the arising of the Italian ”Southern Question”. I then explore a possible channel through which monetary integration might aggravate regional inequality, by investigating the endogenous effects of monetary integration. Looking at the Italian monetary unification, I find evidence in support of Krugman’s (1993) pessimist view on the endogenous effects of monetary integration, where integration- induced specialization and factor mobility increase the risk of asymmetric shocks and regional hysteresis phenomenons. On the other hand, the experience of the Italian and German unification does not seem to be characterized by the OCA endogeneity theorized by Frankel and Rose (1998). -

The Theory of an 'Optimum Currency Area'

THE THEORY OF AN ‘OPTIMUM CURRENCY AREA’ JAROSŁAW KUNDERA* INTRODUCTION The conception of an optimum currency area was elaborated by Canadian economist R. Mundell in his famous article published under the same title in the American Economic Review in September 1961. This theory has been further developed by other economists (R.I. McKinnon, P.B. Kenen and H. Grubel), who refined Mundell’s reasoning. The main goal of this paper is to analyse and distinguish the main components of the optimum currency area. Taking into consideration the experiences from the current crisis in the euro zone, the question arises if the theory of an ‘Optimum Currency Area’ correctly explains the conditions for a functioning monetary union, and if the present euro zone crisis can be explained through it. From the point of view of the EU Member States, it is also interesting to see how this theory, elaborated mainly in 1960–1970, applies to the four freedoms of the European Single Market. In other words, if the economy of a Member State (Poland included) corresponds to the assumptions of the optimum currency area. In every economy, monetary and fiscal policy as the state’s two main economic policies must act in harmony. So the question thus arises of how the fiscal policies in partner states in conditions of a common currency would work. Lack of proper coordination between the centralized monetary policy of the European Central Bank and decentralized fiscal policies in Member States is treated as one of the causes of the current crisis in the euro zone. I. -

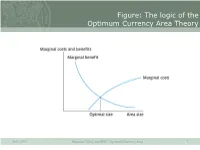

The Logic of the Optimum Currency Area Theory

Figure: The logic of the Optimum Currency Area Theory SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 1 Benefits of a Currency Area • Elimination of transaction costs and comparability of prices. • Elimination of exchange rate risk (for transactions and FDI). • More independent central bank. • Benefits of an international currency. SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 2 Costs of a Currency Area • Costs arise because, when joining monetary union, a country loses monetary policy instrument (e.g. exchange rate) • This is costly when asymmetric shocks occur SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 3 Costs of a Currency Area • The loss of monetary independence fundamentally changes the capacity of governments to finance their budget deficits. • Members of monetary union issue debt in currency over which they have no control. • Liquidity crisis Solvency Crisis. • Stand-alone countries can always create liquidity. (inflation might be a problem but cannot be forced to default against their will!) • This makes a monetary union fragile. SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 4 Costs of a Currency Area • Diversity in a currency area is costly because a common currency makes it impossible to react to each and every local particularity. • The theory of optimum currency areas (OCA) aims at identifying these costs more precisely. SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 5 Shocks and the Exchange Rate SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 6 Asymmetric Shocks SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 7 Other sources of asymmetry • Different labour market institutions – Centralized versus non-centralized wage bargaining – Symmetric shocks (e.g. -

The Political Economy of the Euro Crisis

The Political Economy of the Euro Crisis Mark Copelovitch University of Wisconsin – Madison [email protected] Jeffry Frieden Harvard University [email protected] Stefanie Walter University of Zurich [email protected] Lead article for the special issue “The Political Economy of the Euro Crisis,” forthcoming in Comparative Political Studies The euro crisis has developed into the most serious economic and political crisis in the history of the European Union (EU). By 2016, nine years after the outbreak of the global financial crisis in 2007, economic activity in the EU and the Eurozone was still below its pre- crisis level. At this point, the joint effects of the global financial crisis and the euro crisis have caused more lasting economic damage in Europe than the Great Depression of the 1930s (Crafts, 2013). The political consequences have also been severe. Conflict among EU member states has threatened the progress of European integration, while polarization and unrest have unsettled domestic politics in a host of European countries. The crisis has indeed brought into question the very nature and future of European integration generally, and of monetary integration specifically. To date, there has been substantial economic analysis of the crisis in the Eurozone, which has recently culminated in the emergence of a widely shared consensus on its causes (Baldwin et al., 2015). However, economists often fail to appreciate the large role that politics has played in the run-up, evolution, and attempts at resolution of the euro crisis. The typical economic approach has been to note that the Eurozone is not an optimal currency area 1 , and to subsequently conclude that the long-term survival of the Eurozone requires the creation of a set of institutions to act as substitutes – such as fiscal union, banking union, and/or the establishment of a larger, permanent transfer mechanism to replace the European Stability Mechanism (e.g., De Grauwe, 2013; Lane, 2012; Pisani-Ferry, 2012). -

The Optimum Currency Area Theory and the EMU: an Assessment in the Context of the Eurozone Crisis

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Jager, Jennifer; Hafner, Kurt A. Article — Published Version The optimum currency area theory and the EMU: An assessment in the context of the eurozone crisis Intereconomics Suggested Citation: Jager, Jennifer; Hafner, Kurt A. (2013) : The optimum currency area theory and the EMU: An assessment in the context of the eurozone crisis, Intereconomics, ISSN 1613-964X, Springer, Heidelberg, Vol. 48, Iss. 5, pp. 315-322, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10272-013-0474-7 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/126400 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu DOI: 10.1007/s10272-013-0474-7 Optimum Currency Area Jennifer Jager and Kurt A. -

The Eurozone Crisis: the Theory of Optimum Currency Areas Bites Back

The Eurozone Crisis: The Theory of Optimum Currency Areas Bites Back Barry Eichengreen March 2014 2011 was Europe’s annus horriibilis, arguably the nadir of the Eurozone crisis. It was the year after the crisis surfaced in what were initially dismissed as a handful of small countries with special problems, starting with Greece, Ireland and Portugal, before infecting the monetary union as a whole. It was the year preceding Mario Draghi’s “do whatever it takes” speech which laid to rest fears of Eurozone break-up and ended the acute stage of the crisis. Ironically, 2011 was also the 50th anniversary of Robert Mundell’s classic article “The Theory of Optimum Currency Areas,” which provided the analytical framework through which academics and policy makers think about preconditions for a smoothly functioning monetary union.1 Few other articles published fully 50 years ago in the American Economic Review – much less articles running to just eight short pages – have had such a powerful and enduring influence. In fact, the coincidence of timing was just that, a coincidence. That said, the two events were not entirely unrelated. The theory of optimum currency areas, as developed by Mundell and his followers, led by Ronald McKinnon and Peter Kenen, contained important insights, which is of course why it remained so influential for 50 years.2 But the theory was also incomplete and misleading in important respects, at least as applied to the circumstances of Europe at the turn of the 21st century. As articulated by Mundell, McKinnon and Kenen, the theory of optimum currency areas emphasized convergence, labor mobility and fiscal integration as preconditions for a smoothly functioning monetary union.3 Convergence means greater similarity in the economic structures of participating member states, minimizing the kind of asymmetric shocks that might require a different monetary-policy response in different parts of the monetary union (something that would not be possible following the adoption of a common currency, by definition). -

European Economic and Monetary Integration, and the Optimum Currency Area Theory

EUROPEAN ECONOMY Economic Papers 302| February 2008 European economic and monetary integration and the optimum currency area theory Francesco Paolo Mongelli EUROPEAN COMMISSION EMU@10 Research In May 2008, it will be ten years since the final decision to move to the third and final stage of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), and the decision on which countries would be the first to introduce the euro. To mark this anniversary, the Commission is undertaking a strategic review of EMU. This paper constitutes part of the research that was either conducted or financed by the Commission as source material for the review. Economic Papers are written by the Staff of the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, or by experts working in association with them. The Papers are intended to increase awareness of the technical work being done by staff and to seek comments and suggestions for further analysis. The views expressed are the author’s alone and do not necessarily correspond to those of the European Commission. Comments and enquiries should be addressed to: European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs Publications B-1049 Brussels Belgium E-mail: [email protected] This paper exists in English only and can be downloaded from the website http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications A great deal of additional information is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu) ISBN 978-92-79-08227-6 doi: 10.2765/3306 © European Communities, 2008 European Economic and Monetary Integration, and the Optimum Currency Area Theory Francesco Paolo Mongelli (ECB)∗ Abstract: This essay follows the synergies and complementarities between European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and the optimum currency area (OCA) theory. -

Artificial Currency Units: the Formation of Functional

ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE No. 114, April 1976 ARTIFICIAL CURRENCY UNITS: THE FORMATION OF FUNCTIONAL. CURRENCY AREAS JOSEPH ASCHHEIM AND Y. S. PARK INTERNATIONAL FINANCE SECTION DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Princeton, New Jersey This is the one hundred and fourteenth number,in the series ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE, published from time to time by the International Finance Section of the Department of Economics of Princeton University. Joseph Aschheim is Professor of Economics at The George Washington University. He has served as economic consultant to many governmental and international organi- zations and was Director of Research and Economic Ad- viser to the Governor of the Central Bank of Kenya in 1971-72. In addition to various journal articles, he is the author of Techniques of Monetary Control (1961) and co- author of Macroeconomics: Income and Monetary Theory (/969). 1'. S. Park is Senior Economist in the Treasurer's Department of the World Bank and Professorial Lecturer in International Finance at Georgetown University. Among his many publications are two books, The Eurobond Market (1974) and Oil Money and the World Economy (forthcom- ing), and Essay No. 100 in this series, The Link between Special Drawing Rights and Development Finance. The present essay represents the opinions of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the World Bank or of any organization with which either author has been affiliated. The Section sponsors the essays in this series but takes no further responsibility for the opinions expressed in them. The writers are free to develop their topics as they wish. -

Optimum Currency Area Theory: an Approach for Thinking About Monetary Integration

OPTIMUM CURRENCY AREA THEORY: AN APPROACH FOR THINKING ABOUT MONETARY INTEGRATION Roman Horvath And Lubos Komarek No 647 WARWICK ECONOMIC RESEARCH PAPERS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS Optimum Currency Area Theory: A Framework for Discussion about Monetary Integration Roman Horváth Luboš Komárek* August 2002 Abstract The optimum currency area (OCA) theory tries to answer an almost prohibitively difficult question: what is the optimal number of currencies to be used in one region. The difficulty of the question leads to a low operational precision of OCA theory. Therefore, we argue that the OCA theory is a framework for discussion about monetary integration. We summarize theoretical issues from the classical contributions to the OCA literature in the 1960s to the modern “endogenous view”. A short survey of empirical studies on the OCA theory in the connection with the EMU and the Czech Republic is presented. Finally, we calculate OCA-indexes for the Czech Republic, EU, Germany and Portugal. The index predicts exchange rates variability from the view of traditional OCA criteria and asseses benefit-cost ratio of implementing common currency for a pair of the countries. We compare the structural similarity of the Czech Republic and Portugal to the German economy and find that the Czech economy is closer. The results are reversed when the EU economy is considered as a benchmark country. Keywords: Optimum currency area theory, central banking, transition, European Union JEL Classification: E32, F42, E42, F33 * Roman Horvath – student at Central European University, Hungary and Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University, The Czech Republic, e-mail: [email protected]. Lubos Komarek – Advisor to Bank Board Member, The Czech National Bank, Prague, Assistant Professor at University of Economics Prague, The Czech Republic and a former student at the University of Warwick, e-mail: [email protected]. -

The Roots of the Euro

Munich Personal RePEc Archive The roots of the Euro Labrinidis, George Ministry of Economy, General Secretary Of Industry, Athens University of Economics and Business 23 April 2018 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/86560/ MPRA Paper No. 86560, posted 11 May 2018 13:17 UTC Voice of People Discussion Papers #6 The roots of the Euro George Labrinidis Address: Ministry of Economy, General Secretary Of Industry, Kanningos Square 20, 10200, Athens, Greece Email: [email protected] Voice Of People www.voiceofpeople.eu Email: [email protected] Abstract Indisputably, the euro has played a pivotal role in the development of Europe. Yet, the euro has also been very controversial, raising many discussions related to the nature, role and form of the “common currency”. This paper aims at contributing to this ongoing debate from a Marxist perspective, presenting the theoretical framework of quasi-world money and examining the evolution of the euro as such, from the 1950s when the idea appeared for the first time. In particular, the paper focuses on the processes that led to the emergence of the euro as quasi- world money. These processes comprised a series of political solutions to the contradiction between the necessity of all major European countries to impose their money on the European market on the one hand, and their incompetence in doing so, on the other. The analysis focuses on the post-war European monetary system up until the launch of the European Monetary Union. Its object is a historical monetary compromise that passed through many phases and managed to survive until the present day. -

Optimal Currency Areas

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2002, Volume 17 Volume Author/Editor: Mark Gertler and Kenneth Rogoff, editors Volume Publisher: MIT Press Volume ISBN: 0-262-07246-7 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gert03-1 Conference Date: April 5-6, 2002 Publication Date: January 2003 Title: Optimal Currency Areas Author: Alberto Alesina, Robert J. Barro, Silvana Tenreyro URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11077 Alberto Alesina, RobertJ. Barro, and Silvana Tenreyro HARVARDUNIVERSITY, NBER, AND CPER;HARVARD UNIVERSITY,HOOVER INSTITUTION, AND NBER;AND FEDERAL RESERVEBANK OF BOSTON Optimal Currency Areas 1. Introduction Is a country by definition an optimal currency area? If the optimal number of currencies is less than the number of existing countries, which countries should form currency areas? This question, analyzed in the pioneering work of Mundell (1961) and extended in Alesina and Barro (2002), has jumped to the center stage of the current policy debate, for several reasons. First, the large increase in the number of independent countries in the world led, until recently, to a roughly one-for-one increase in the number of currencies. This prolifera- tion of currencies occurred despite the growing integration of the world economy. On its own, the growth of international trade in goods and assets should have raised the transactions benefits from common curren- cies and led, thereby, to a decline in the number of independent moneys. Second, the memory of the inflationary decades of the seventies and eight- ies encouraged inflation control, thereby generating consideration of ir- revocably fixed exchange rates as a possible instrument to achieve price stability.