Optimal Currency Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Macroeconomic Model with Financial Panics Gertler, Mark, Nobuhiro Kiyotaki, and Andrea Prestipino

K.7 A Macroeconomic Model with Financial Panics Gertler, Mark, Nobuhiro Kiyotaki, and Andrea Prestipino Please cite paper as: Gertler, Mark, Nobuhior Kiyotaki, and Andrea Prestipino (2017). A Macroeconomic Model with Financial Panics. International Finance Discussion Papers 1219. https://doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.2017.1219 International Finance Discussion Papers Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Number 1219 December 2017 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System International Finance Discussion Papers Number 1219 December 2017 A Macroeconomic Model with Financial Panics Mark Gertler, Nobuhiro Kiyotaki and Andrea Prestipino NOTE: International Finance Discussion Papers are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment. References to International Finance Discussion Papers (other than an acknowledgment that the writer has had access to unpublished material) should be cleared with the author or authors. Recent IFDPs are available on the Web at www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdp/. This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network electronic library at www.ssrn.com. A Macroeconomic Model with Financial Panics Mark Gertler, Nobuhiro Kiyotaki and Andrea Prestipino NYU, Princeton and Federal Reserve Board December, 2017 Abstract This paper incorporates banks and banking panics within a conven- tional macroeconomic framework to analyze the dynamics of a financial crisis of the kind recently experienced. We are particularly interested in characterizing the sudden and discrete nature of the banking panics as well as the circumstances that makes an economy vulnerable to such panics in some instances but not in others. Having a conventional macroeconomic model allows us to study the channels by which the crisis a¤ects real activity and the e¤ects of policies in containing crises. -

The Theory of Optimum Currency Areas and Business Cycle Synchronization in Central and Eastern European Countries

TALLINN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Tallinn School of Economics and Business Administration Department of Finance and Economics Chair of Finance and Banking Natalia Levenko THE THEORY OF OPTIMUM CURRENCY AREAS AND BUSINESS CYCLE SYNCHRONIZATION IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES Master’s thesis Supervisor: Professor Karsten Staehr Tallinn 2014 I declare I have written the master’s thesis independently. All works and major viewpoints of the other authors, data from other sources of literature and elsewhere used for writing this paper have been referenced. Natalia Levenko …………………………… (signature, date) Student’s code: 122351 Student’s e-mail address: [email protected] Supervisor: Professor Karsten Staehr The paper conforms to the requirements set for the master’s thesis …………………………………………… (signature, date) Chairman of defence committee: Permitted to defence …………………………………………… (title, name, signature, date) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 5 2. THEORETICAL STUDIES ................................................................................................... 8 2.1. The theory of the optimum currency areas ........................................................................ 8 2.1.1. The original theory ................................................................................................... -

Euro Zone Debt Crisis: Theory of Optimal Currency Area

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UGD Academic Repository UDC 339.738(4-672EU) Original scientific paper Vesna GEORGIEVA SVRTINOV1) Diana BOSKOVSKA 2) Aleksandra LOZANOSKA3) Olivera GJORGIEVA-TRAJKOVSKA4) EURO ZONE DEBT CRISIS: THEORY OF OPTIMAL CURRENCY AREA Abstract Creation of a monetary union, carries along certain costs and benefits. Benefits of monetary union mainly stem from reducing transaction costs and eliminating exchange-rate uncertainty. On the other side, a country that joins a currency union, therefore gives up the opportunity to select a monetary policy, that it regards as optimal for its own circumstances. In this paper we explain the criteria of optimum currency area (OCA): degree of trade, similarity of business cycles, degree of labor and capital mobility and system of risk sharing. Viewed through the prism of these criteria, EMU is currently far from being an optimal currency area, especially in fulfillment criteria of labor mobility and fiscal integration. The aim of the paper is to highlight certain shortcomings of the EMU, such as its vulnerability to asymmetric shocks and its inability to act as predicted by the theory of optimum currency areas. Furthermore, we explain the reasons behind the difficulties that the euro area faced, and the problems that led to the outbreak of the sovereign debt crisis. At 1) PhD, “Ss. Cyril and Methodius University” in Skopje, Institute of Economics- Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, e-mail: [email protected]. 2) PhD, “Ss. Cyril and Methodius University” in Skopje, Institute of Economics-Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, e-mail: [email protected] 3) PhD, “Ss. -

Monetary Policy Rules and Macroeconomic Stability: Evidence and Some Theory*

MONETARY POLICY RULES AND MACROECONOMIC STABILITY: EVIDENCE AND SOME THEORY* RICHARD CLARIDA JORDI GALI´ MARK GERTLER We estimate a forward-looking monetary policy reaction function for the postwar United States economy, before and after Volcker’s appointment as Fed Chairman in 1979. Our results point to substantial differences in the estimated rule across periods. In particular, interest rate policy in the Volcker-Greenspan period appears to have been much more sensitive to changes in expected ination than in the pre-Volcker period. We then compare some of the implications of the estimated rules for the equilibrium properties of ination and output, using a simple macroeconomic model, and show that the Volcker-Greenspan rule is stabilizing. I. INTRODUCTION From the late 1960s through the early 1980s, the United States economy experienced high and volatile ination along with several severe recessions. Since the early 1980s, however, ina- tion has remained steadily low, while output growth has been relatively stable. Many economists cite supply shocks—and oil price shocks, in particular—as the main force underlying the instability of the earlier period. It is unlikely, however, that supply shocks alone could account for the observed differences between the two eras. For example, while jumps in the price of oil might help explain transitory periods of sharp increases in the general price level, it is not clear how they alone could explain persistent high ination in the absence of an accommodating monetary policy.1 Furthermore, as De Long {1997} argues, the onset of sustained high ination occurred prior to the oil crisis episodes. * We thank seminar participants at Universitat Pompeu Fabra, New York University, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, University of Maryland, NBER Summer Institute, Universite´ de Toulouse, Bank of Spain, Harvard University, Bank of Mexico, Universitat de Girona, and the Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta, New York, Richmond, Dallas, and Philadelphia, as well as two anonymous referees and two editors for useful comments. -

Optimum Currency Areas and European Monetary Integration: Evidence from the Italian and German Unifications

Optimum Currency Areas and European Monetary Integration: Evidence from the Italian and German Unifications Roger Vicquery´ * London School of Economics November 2017 Abstract Recent events have sparked renewed research interest in international monetary integration and currency areas. This paper provides new empirical evidence on the predictive power and endogeneity of the Optimum Currency Areas (OCA) framework, by analyzing the wave of European monetary integration occuring between 1852 and the establishment of the international gold standard. This period witnessed to the creation of two national monetary unions lasting to this day, Italy and Germany, as well as monetary integration around Britain and France. I estimate the ex-ante optimality of various monetary arrangements, relying on a newly collected dataset allowing to proxy the assymetry of shocks across European regions. My findings support the predictive power of the OCA framework. In particular, I find that, opposite to Germany, Italian pre-unitary states did not form an OCA at unification. I argue that this might have contributed to the arising of the Italian ”Southern Question”. I then explore a possible channel through which monetary integration might aggravate regional inequality, by investigating the endogenous effects of monetary integration. Looking at the Italian monetary unification, I find evidence in support of Krugman’s (1993) pessimist view on the endogenous effects of monetary integration, where integration- induced specialization and factor mobility increase the risk of asymmetric shocks and regional hysteresis phenomenons. On the other hand, the experience of the Italian and German unification does not seem to be characterized by the OCA endogeneity theorized by Frankel and Rose (1998). -

The Theory of an 'Optimum Currency Area'

THE THEORY OF AN ‘OPTIMUM CURRENCY AREA’ JAROSŁAW KUNDERA* INTRODUCTION The conception of an optimum currency area was elaborated by Canadian economist R. Mundell in his famous article published under the same title in the American Economic Review in September 1961. This theory has been further developed by other economists (R.I. McKinnon, P.B. Kenen and H. Grubel), who refined Mundell’s reasoning. The main goal of this paper is to analyse and distinguish the main components of the optimum currency area. Taking into consideration the experiences from the current crisis in the euro zone, the question arises if the theory of an ‘Optimum Currency Area’ correctly explains the conditions for a functioning monetary union, and if the present euro zone crisis can be explained through it. From the point of view of the EU Member States, it is also interesting to see how this theory, elaborated mainly in 1960–1970, applies to the four freedoms of the European Single Market. In other words, if the economy of a Member State (Poland included) corresponds to the assumptions of the optimum currency area. In every economy, monetary and fiscal policy as the state’s two main economic policies must act in harmony. So the question thus arises of how the fiscal policies in partner states in conditions of a common currency would work. Lack of proper coordination between the centralized monetary policy of the European Central Bank and decentralized fiscal policies in Member States is treated as one of the causes of the current crisis in the euro zone. I. -

The Robustness and Efficiency of Monetary Policy Rules As Guidelines

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Taylor, John B. Working Paper The robustness and efficiency of monetary policy rules as guidelines for interest rate setting by the European Central Bank: Conference on Monetary Policy Rules, Stockholm 12 - 12 June 1998 Sveriges Riksbank Working Paper Series, No. 58 Provided in Cooperation with: Central Bank of Sweden, Stockholm Suggested Citation: Taylor, John B. (1998) : The robustness and efficiency of monetary policy rules as guidelines for interest rate setting by the European Central Bank: Conference on Monetary Policy Rules, Stockholm 12 - 12 June 1998, Sveriges Riksbank Working Paper Series, No. 58, Sveriges Riksbank, Stockholm This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/83027 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Finance and Growth: When Credit Helps, and When It Hinders

Session “Socially Useful Financial Systems” Bezemer – ‘When Credit Helps, and When it Hinders’ Finance and Growth: When Credit Helps, and When it Hinders Dirk J Bezemer, University Groningen ([email protected] ) EXTENDED SUMMARY The financial sector can support growth but it can also cause crisis. The present crisis has exposed gaps in economists’ understanding of this dual potential. This paper grounds an alternative approach in the credit nature of money, and in an older distinction between credit flows that grow the economy of goods and services (the GDP), and credit that inflates markets for financial assets and property. This increases the debt-to-GDP ratio and can be a helpful catalyst of the real sector. But if it overshoots, it leads to bloated financial markets and the pursuit of capital gains rather than profit, with rising costs due to high asset values, rising inequality, falling fixed capital formation, rising uncertainty, and fraud and corruption. Unfortunately, overshooting is built into the system due to the nature of money, banking and compound interest. That is why financial deregulation leads to credit booms and busts. A return to financially sustainable growth in the longer term requires a shrinking of the mortgage, consumer credit and nonbank financial sector which is a creditor to the real sector, and absorbs a continuing flow of liquidity in interest payment and financial fees that would otherwise be effective demand for goods and services, supporting economic growth. Financial deregulation has allowed the US ‘FIRE’ sector to grow to about three times the size it had in the 1980s and so its claims on the real sector are three times larger than a quarter century ago. -

Mark Gertler Becomes Newest Resident Scholar

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Number 2 2006 ResearchUpdate Research and Statistics Group www.newyorkfed.org/research Mark Gertler Becomes Newest Resident Scholar he Research Group welcomes Mark and has been a visiting scholar at the Gertler to its Program for Resident Federal Reserve Bank of New York on T Scholars for 2006-07. and off since 1994. Professor Gertler, the Henry and Lucy Professor Gertler joins current resident Moses Professor of Economics at NYU scholars Nobuhiro Kiyotaki of the London and Chair of the Economics Department, School of Economics and Suresh M. is known for his research on macroeco- Sundaresan of Columbia Business School. nomic theory, monetary economics, and The Research Group established its finance. He has published extensively, Program for Resident Scholars in 2004 coauthoring with Ben Bernanke, Glenn to attract to the New York Fed, for a stay Hubbard, and Mark Watson, and his work of at least six months, outstanding has appeared in the American Economic researchers with an international reputa- Review, the Journal of Political Economy, tion. The scholars are selected from the the Quarterly Journal of Economics, and top academic and policy institutions in the Review of Economic Studies. areas related to the Bank’s broad policy Professor Gertler has a distinguished career in academia. He is also a coeditor interests. Resident scholars pursue their of the American Economic Review and own research agendas while participating has been on the editorial boards of the fully in the Group’s activities. They work Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking; closely with the director of research, con- Economics Letters; the NBER tribute to policymaking discussions, and Macroeconomics Annual; and the Journal provide intellectual leadership by advising of Financial Intermediation. -

Working Paper No

Working Paper No. 384 Minsky's Acceleration Channel and the Role of Money by Greg Hannsgen The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College July 2003 Address for correspondence: G. Hannsgen The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College Blithewood Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y. 12504-5000 U.S.A. Phone: (845) 758-7721 email: [email protected] The author wishes to thank Philip Arestis for extensive and useful comments on earlier drafts and Steve Fazzari for helpful advice at the outset of the project. He thanks Kenneth Hannsgen and Greg Colman for comments on the second draft and Hannsgen for a calculation as indicated in a footnote below. These individuals are not responsible for any remaining errors. 1. INTRODUCTION Fifteen to twenty years after the endogenous supply of money became a cornerstone of post-Keynesian economics (Moore 1979, 1988a, 1988b; Rousseas, 1986; Wray 1990; Kaldor 1970, 1985), the ways in which monetary policy affects the economy are not yet widely agreed upon by heterodox economists (see, for example, Rogers 1989; Davidson 2002, ch. 7). This issue has taken on a new urgency as efforts to stimulate the economy through monetary policy are failing in Japan and having little effect in the United States (Belson 2003) . In the simplest version of the post-Keynesian view, banks are price setters (or rather, interest rate setters) and quantity takers; that is, they are free to set the interest rate at which they provide loans, but have no control over the volume of their lending. Hence, most post-Keynesian innovators of monetary endogeneity attribute the effects of monetary conditions almost entirely to the level of the central bank-determined interest rate, which is marked up by commercial banks to obtain an appropriate lending rate. -

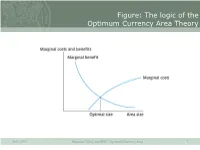

The Logic of the Optimum Currency Area Theory

Figure: The logic of the Optimum Currency Area Theory SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 1 Benefits of a Currency Area • Elimination of transaction costs and comparability of prices. • Elimination of exchange rate risk (for transactions and FDI). • More independent central bank. • Benefits of an international currency. SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 2 Costs of a Currency Area • Costs arise because, when joining monetary union, a country loses monetary policy instrument (e.g. exchange rate) • This is costly when asymmetric shocks occur SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 3 Costs of a Currency Area • The loss of monetary independence fundamentally changes the capacity of governments to finance their budget deficits. • Members of monetary union issue debt in currency over which they have no control. • Liquidity crisis Solvency Crisis. • Stand-alone countries can always create liquidity. (inflation might be a problem but cannot be forced to default against their will!) • This makes a monetary union fragile. SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 4 Costs of a Currency Area • Diversity in a currency area is costly because a common currency makes it impossible to react to each and every local particularity. • The theory of optimum currency areas (OCA) aims at identifying these costs more precisely. SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 5 Shocks and the Exchange Rate SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 6 Asymmetric Shocks SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: Optimum Currency Area 7 Other sources of asymmetry • Different labour market institutions – Centralized versus non-centralized wage bargaining – Symmetric shocks (e.g. -

June 2020 Ph.D., Columbia University, New York, 1988. Advisor

June 2020 CARMEN M. REINHART CURRICULUM VITAE EDUCATION Ph.D., Columbia University, New York, 1988. Advisor: Robert Mundell. Doctoral Dissertation: “Real Exchange Rates, Commodity Prices, and Policy Interdependence.” M. Phil., 1981 and M.A., Columbia University, New York, 1980. B.A., Florida International University, Miami, 1978. PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Chief Economist and Vice President, World Bank, Washington DC, June 2020- Minos A. Zombanakis Professor of the International Financial System, Harvard Kennedy School, July 2012 – Dennis Weatherstone Chair, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington DC, 2011 – June 2012. Director, Center for International Economics, 2009-2010; Professor, School of Public Policy and Department of Economics, 2000 – 2010; Director, International Security and Economic Policy Specialization, 1998 – 2001; Associate Professor School of Public Policy, University of Maryland, 1996 – 2000. Senior Policy Advisor and Deputy Director, Research Department, 2001 – 2003. Senior Economist and Economist, 1988 - 1996, International Monetary Fund. Chief Economist and Vice President, 1985 – 1986; Economist, March 1982 - 1984, Bear Stearns, New York. AWARDS AND HONORS Karl Brunner Award, Swiss National Bank, planned September 2021. Mundell-Fleming Lecture, International Monetary Fund, planned November 2020. Economica, Coase-Phillips Lecture, London School of Economics, London, May 2020. FIMEF Diamond Finance Award, Instituto Mexicano de Ejecutivos de Finanzas, Mexico, August 2019. Homer Jones Memorial Lecture, St. Louis Federal Reserve, July 2019. Thomas Schelling Lecture, University of Maryland, April 2019. Carmen M. Reinhart Pa ge 1 King Juan Carlos Prize in Economics, December 2018. Wiki. Bernhard Harms Prize, Kiel Institute for the World Economy. October 2018. Adam Smith Award, National Association of Business Economists, September 2018. William F. Butler Award, New York Association for Business Economists, September 2017.