Snapshots of COVID-19: Structural Inequity and Access to Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saia, David Joseph (1904-1990), Papers, 1938-1990

Pittsburg State University Pittsburg State University Digital Commons Finding Aids Special Collections & University Archives 3-2012 Saia, David Joseph (1904-1990), Papers, 1938-1990 Special Collections, Leonard H. Axe Library Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/fa Recommended Citation Special Collections, Leonard H. Axe Library, "Saia, David Joseph (1904-1990), Papers, 1938-1990" (2012). Finding Aids. 71. https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/fa/71 This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections & University Archives at Pittsburg State University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Pittsburg State University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72 Saia, David Joseph (1904-1990), Papers, 1938-1990 2.5 linear feet 1 INTRODUCTION Personal and professional correspondence, organizational newsletters, legal documents, and other items collected by David J. “Papa Joe” Saia during his tenure as Crawford County Commissioner and chairman of the Crawford County Democratic Party. DONOR INFORMATION The David Joseph Saia Papers were donated to Pittsburg State University by Mr. Saia on 28 July 1975. Materials in the collection dated after 1975 were compiled by curator Eugene DeGruson. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH David Joseph “Papa Joe” Saia was a long-time resident of Frontenac, Kansas and one of the most prominent figures in the Kansas Democratic Party. Saia was born on 2 May 1904 in Chicopee, Kansas and began working in the coal fields of Crawford County at age thirteen. His political career began at the same time as a member of the United Mine Workers “pit committee,” a group which carried grievances to the pit bosses in the mines. -

Federal Election Commission 1 2 First General Counsel's

MUR759900019 1 FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION 2 3 FIRST GENERAL COUNSEL’S REPORT 4 5 MUR 7304 6 DATE COMPLAINT FILED: December 15, 2017 7 DATE OF NOTIFICATIONS: December 21, 2017 8 DATE LAST RESPONSE RECEIVED September 4, 2018 9 DATE ACTIVATED: May 3, 2018 10 11 EARLIEST SOL: September 10, 2020 12 LATEST SOL: December 31, 2021 13 ELECTION CYCLE: 2016 14 15 COMPLAINANT: Committee to Defend the President 16 17 RESPONDENTS: Hillary Victory Fund and Elizabeth Jones in her official capacity as 18 treasurer 19 Hillary Rodham Clinton 20 Hillary for America and Elizabeth Jones in her official capacity as 21 treasurer 22 DNC Services Corporation/Democratic National Committee and 23 William Q. Derrough in his official capacity as treasurer 24 Alaska Democratic Party and Carolyn Covington in her official 25 capacity as treasurer 26 Democratic Party of Arkansas and Dawne Vandiver in her official 27 capacity as treasurer 28 Colorado Democratic Party and Rita Simas in her official capacity 29 as treasurer 30 Democratic State Committee (Delaware) and Helene Keeley in her 31 official capacity as treasurer 32 Democratic Executive Committee of Florida and Francesca Menes 33 in her official capacity as treasurer 34 Georgia Federal Elections Committee and Kip Carr in his official 35 capacity as treasurer 36 Idaho State Democratic Party and Leroy Hayes in his official 37 capacity as treasurer 38 Indiana Democratic Congressional Victory Committee and Henry 39 Fernandez in his official capacity as treasurer 40 Iowa Democratic Party and Ken Sagar in his official capacity as 41 treasurer 42 Kansas Democratic Party and Bill Hutton in his official capacity as 43 treasurer 44 Kentucky State Democratic Central Executive Committee and M. -

Funding the State Political Party Committees Pre- and Post-BCRA, 1999–2016

Funding the State Political Party Committees Pre- and Post-BCRA, 1999–2016 Analysis by the National Institute on Money in State Politics: Edwin Bender, Calder Burgam, Ciara O’Neill, Pete Quist, Denise Roth Barber, Greg Schneider, J T Stepleton Prepared for the Bauer Ginsberg Campaign Finance Research Task Force, May 15, 2017 National Institute on Money in State Politics, 833 N. Last Chance Gulch Helena, MT 59601, 406-449-2480, www.FollowTheMoney.org Submitted May 15, 2017 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................................................ 5 FUNDING THE STATE PARTY COMMITTEES ....................................................................................................................... 8 CONTRIBUTIONS FROM WITHIN THE POLITICAL PARTY SYSTEM ................................................................................................................ 9 CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OUTSIDE THE POLITICAL PARTY SYSTEM ............................................................................................................ -

Democratic Change Commission

Report of the Democratic Change Commission Prepared by the DNC Office of Party Affairs and Delegate Selection as staff to the Democratic Change Commission For more information contact: Democratic National Committee 430 South Capitol Street, S.E. Washington, DC 20003 www.democrats.org Report of the Democratic Change Commission TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter of Transmittal ..................................................................................................................1 Introduction and Background ...................................................................................................3 Creation of the Democratic Change Commission DNC Authority over the Delegate Selection Process History of the Democratic Presidential Nominating Process ’72-‘08 Republican Action on their Presidential Nominating Process Commission Meeting Summaries ............................................................................................13 June 2009 Meeting October 2009 Meeting Findings and Recommendations ..............................................................................................17 Timing of the 2012 Presidential Nominating Calendar Reducing Unpledged Delegates Caucuses Appendix ....................................................................................................................................23 Democratic Change Commission Membership Roster Resolution Establishing the Democratic Change Commission Commission Rules of Procedure Public Comments Concerning Change Commission Issues Acknowledgements Report -

The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network

PLATFORMS AND OUTSIDERS IN PARTY NETWORKS: THE EVOLUTION OF THE DIGITAL POLITICAL ADVERTISING NETWORK Bridget Barrett A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Daniel Kreiss Adam Saffer Adam Sheingate © 2020 Bridget Barrett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Bridget Barrett: Platforms and Outsiders in Party Networks: The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network (Under the direction of Daniel Kreiss) Scholars seldom examine the companies that campaigns hire to run digital advertising. This thesis presents the first network analysis of relationships between federal political committees (n = 2,077) and the companies they hired for electoral digital political advertising services (n = 1,034) across 13 years (2003–2016) and three election cycles (2008, 2012, and 2016). The network expanded from 333 nodes in 2008 to 2,202 nodes in 2016. In 2012 and 2016, Facebook and Google had the highest normalized betweenness centrality (.34 and .27 in 2012 and .55 and .24 in 2016 respectively). Given their positions in the network, Facebook and Google should be considered consequential members of party networks. Of advertising agencies hired in the 2016 electoral cycle, 23% had no declared political specialization and were hired disproportionately by non-incumbents. The thesis argues their motivations may not be as well-aligned with party goals as those of established political professionals. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES .................................................................................................................... V POLITICAL CONSULTING AND PARTY NETWORKS ............................................................................... -

Community Choice Act National Kickoff Draws Thousands

Volume 22 no.8 A Publication of ADAPT Fall 2009 Contents | Around the Nation | Passages Community Choice Act National Kickoff Draws Thousands Reprinted from ADAWatch.org, March 24, 2009 ADAPT’s National Kickoff for the Community Choice Act concluded in Washington, DC with a rally call to “Pass CCA Now! With thousands of advocates in DC and at more than 120 conference callin sites across the country, Community Choice Act (CCA) cosponsors Senator Tom Harkin, Senator Arlen Specter and Congressman Danny Davis made crystal clear their commitment to passing the Community Choice Act in the 111th Congress. The event was an upbeat event at times filled with thunderous applause and the chanting of “Pass CCA Now!” Sen. Tom Harkin led off this important event on Capitol Hill and declared that CCA will pass in this Congress and be on the President’s desk either as a part of the healthcare reform bill or on its own. He noted that it has been 10 years since the Supreme Court’s Olmstead decision which affirmed the Constitutional rights of people with disabilities to live in the least restrictive environment and he told the critics who say CCA will cost too much that by allowing individuals with disabilities to live and work in their own homes and communities rather than institutions, the costs will be offset by new taxpayers. Harkin declared: “We can’t afford not to do this!” ADA Watch and the National Coalition for Disability Rights (NCDR) are longtime supporters of CCA, formally known as MiCASSA, the legislation that gives people real choice in long term care options. -

Kathleen Sebelius, Governor of Kansas, 2003-2009

Kathleen Sebelius, governor of Kansas, 2003-2009. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 40 (Winter 2017–2018): 262-289 262 Kansas History “Find a Way to Find Common Ground”: A Conversation with Former Governor Kathleen Sebelius edited by Bob Beatty and Linsey Moddelmog athleen Mary (Gilligan) Sebelius, born May 15, 1948, in Cincinnati, Ohio, served as the State of Kansas’s forty-fourth chief executive from January 13, 2003, to April 28, 2009, when she resigned to serve in President Barack Obama’s cabinet as secretary for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Sebelius rose to the governorship after serving in the Kansas House of Representatives from 1987 to 1995 and serving two terms as Kansas insurance commissioner from 1995 to 2003. She was the first insurance commissioner from the Democratic Party in Kansas history, defeating Republican Kincumbent Ron Todd in 1994, 58.6 percent to 41.4 percent. She ran for reelection in 1998 and easily defeated Republican challenger Bryan Riley, 59.9 to 40.1 percent. In the 2002 gubernatorial race, Sebelius defeated Republican state treasurer Tim Shallenburger, 52.9 to 45.1 percent. She won reelection in 2006 by a vote of 57.9 to 40.4 percent against her Republican challenger, state senator Jim Barnett.1 Sebelius never lost an election to public office in Kansas.2 Sebelius’s 2002 gubernatorial victory marked the first and only father-daughter pair to serve as governors in the United States. Her father, John Gilligan, was Democratic governor of Ohio from 1971 to 1975. Sebelius’s gubernatorial leadership style was one of bipartisanship, as her Democratic Party was always in the minority in the state legislature. -

Nationalelectionis Unfinished Matter

Thursday November 16, 2000 Section A Campus Ledger " * _ ■ _ _____ Mwk.kwKf "_ "_i irr " " Lucky DeBellevue " Capture the flag has Women's team pre- gives pipe cleaners new been reborn; paintball is _H__VpE pares for repeat of last meaning in his exhibit makingits presence felt. year's championship. _u H at theGallery of Art. A4 , "A B6 _B B2 National election is unfinished matter RobertHki.mer ingin from overseas(dueNov.17). which histori- Reporter Staff cally tend to be Republican. ._____■ £_____ ___r^ _ In Douglas County, voters began receiving Painfully close national elections have unusual phone calls early Tuesday morning. A drawn high voter turnout and a storm of contro- man, claiming to be working for the Kansas versy. The presidentialrace now hingeson Flori- Democratic Party, told voters their voter registra- da;more than a week after the election,the battle tion cards would be required in order to vote, between Vice President Al Gore and Gov. warning that violation of state election laws was George W. Bush continues incourt over recounts serious business. Kansas, however, operates on of ballets in four counties. The contests for the an honor system; voters are not required to pre- 3rd Congressional district inKansas and the Sen- wr^^ \\M^ sent any identification at the polls. ate seat held by John Ashcroft in Missouri The Kansas Democratic Party has denied reflected the national trend of tight races with the any connection to the phone calls. Though a candidates fighting right up until thepolls closed. Republican misinformation plot is appealing to The Bush-Gore campaign has effectively conspiracy theorists, no evidence of Republican split the American popular vote. -

I State Political Parties in American Politics

State Political Parties in American Politics: Innovation and Integration in the Party System by Rebecca S. Hatch Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John H. Aldrich, Supervisor ___________________________ Kerry L. Haynie ___________________________ Michael C. Munger ___________________________ David W. Rohde Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 i v ABSTRACT State Political Parties in American Politics: Innovation and Integration in the Party System by Rebecca S. Hatch Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John H. Aldrich, Supervisor ___________________________ Kerry L. Haynie ___________________________ Michael C. Munger ___________________________ David W. Rohde An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 Copyright by Rebecca S. Hatch 2016 Abstract What role do state party organizations play in twenty-first century American politics? What is the nature of the relationship between the state and national party organizations in contemporary elections? These questions frame the three studies presented in this dissertation. More specifically, I examine the organizational development -

Kansas Democrats Are Seeing Red, but Not for the Reasons You'd Expect

Kansas Democrats are seeing red, but not for the reasons you'd expect The Pitch Politico The Pitch JOIN THE CONVERSATION! dumb dumb dumb dumb dumb dumb dumb dumb dumb Democrats will never get anywhere by pretending to be more like Republicans who broke it broke it broke it broke it broke it City-states are the answer. Take Trump's Wall and put it between Larrytown and Topeka. Problem solved. Let em have Western Kansas. By acting "more Republican", you've handed the race to the Republican. That has happened at the local level, and it has happened at the national level. Grow a pair and be Democrats and not worry about how the national party is moving left. Republicans have moved the entire playing eld to the right for the past decade and a half. Get behind Bernie Sanders who is speaking plain truths to Americans. Help people who need it and tell the Koch brothers to go away! What's the difference between a Democrat and a Socialist? Apparently the head of the Democratic National Committee is unable to answer that question from two different reporters! Democrats have a much bigger problem than any Kansas issue. http://www.realclearpolitics.com/video/2015/07/30/chris_matthews_to_debbie_wasserman_schultz_whats_the_difference_between_a_democrat_an Thanks for the mention. There are other Democrats who will run in '16. If anyone would like to keep tabs on my campaign, it is facebook.com/Ski4KansasSenate21 Meeker, the last thing Democrats want is to become more like Republicans. How did we get stuck with a Blue Dog running our party?? Because obviously the way to energize the Democratic base in Kansas is to make sure it's impossible to tell the difference between their candidates and the Republicans. -

Amanda Adkins Was One of Former Governor Sam

Amanda Adkins was one of former Governor Sam Brownback’s closest advisors, calling him quote “an incredible governor.” Adkins supported Brownback’s tax handouts for big corporations paid for with major cuts to public school budgets. Now, our schools are struggling to pay for the safety precautions needed for students and teachers to safely return to the classroom. Adkins Was Appointed By Brownback To Be Head Of The Kansas Children’s Cabinet. “A former chairwoman of the Kansas Republican Party and longtime adviser to former Gov. Sam Brownback has entered the race to take on Democratic U.S. Rep. Sharice Davids next year. [...] Adkins chaired the state party from 2009 to 2013, overseeing the 2010 election when Republicans, with Brownback at the top of the ticket in the race for governor, won every federal and statewide office. She managed Brownback’s 2004 campaign for U.S. Senate and after he became governor he appointed Adkins to chair the Kansas Children’s Cabinet and Trust Fund, which oversees a variety of childhood programs.” [The Kansas City Star, 9/3/19] Adkins Was Endorsed By Sen. Brownback For GOP Party Chair. “Adkins, of Overland Park, was elected by GOP delegates without opposition to replace Kris Kobach, who stepped aside to prepare his 2010 campaign for secretary of state. She received a key endorsement from Sen. Sam Brownback, who is running for governor.” [New GOP Chair Stressed Winning, Topeka Capital-Journal, 2/1/09] Brownback Praised Adkins For Running His Successful Senate Re-Election Campaign. “Adkins has served on several congressional staffs, worked with the Heritage Foundation and managed Brownback’s last Senate campaign. -

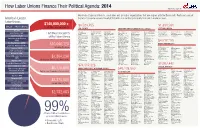

How Labor Unions Finance Their Political Agenda: 2014 Employeerightsact.Com

How Labor Unions Finance Their Political Agenda: 2014 employeerightsact.com Hundreds of special interests, candidates and pro-labor organizations that are aligned with the Democratic Party and support America’s Largest big labor’s agenda received nearly $140 million in funding principally from union member dues. Labor Unions $140,000,000 + $4,529,795 $1,830,986 MAJOR LABOR UNIONS to Left-Wing Special Interests CIVIL RIGHTS DEMOCRATIC PARTY & ALIGNED GROUPS (continued) LEFT-WING MEDIA AFL-CIO 21 Progress The Illinois Coalition for New Americans Central Committee Progressive Democrats of Wisconsin WOMEN VOTE! American Prospect Center for Media and The Nation Institute Auto Workers (UAW) A. Philip Randolph Immigrant and Refugee National Urban League Kitsap Committee for America Workers’ Defense Action Netroots Nation Democracy The Progressive, Inc Five Major Recipients Institute Rights New York Immigration Democracy Progressive Majority Fund Center for American Ed Schultz Broadcasting Uptake Institute Carpenters (CJA) Advancement Project Jewish Labor Committee Coalition Leadership For Jobs and Progressive States Working Families Party of Progress Action Fund Progress Illinois Cloud Tiger Media of Big Labor Money Alliance for Citizenship Labor Coalition for Ohioans for a Voters Bill Leading For Change Network New York Communications Workers American Immigration Community Action of Rights League of Young Voters Project New America Working Families for a Council Latino Policy Forum People First Voting Project Local Experience We Robert F. Kennedy