Counternarcotics: Dsn: 312-664-0378 Lessons from the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy (name redacted) Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs (name redacted) Analyst in Middle Eastern Affairs November 7, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RL30588 Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Summary The United States, partner countries, and the Afghan government are attempting to reverse recent gains made by the resilient Taliban-led insurgency since the December 2014 transition to a smaller international mission consisting primarily of training and advising the Afghanistan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF). The Afghan government has come under increasing domestic criticism not only for failing to prevent insurgent gains but also for its internal divisions that have spurred the establishment of new political opposition coalitions. In September 2014, the United States brokered a compromise to address a dispute over the 2014 presidential election, but a September 2016 deadline was not met for enacting election reforms and deciding whether to elevate the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) position to a prime ministership. The Afghan government has made some measurable progress in reducing corruption and implementing its budgetary and other commitments. It has adopted measures that would enable it to proceed with new parliamentary elections, but no election date has been set. The number of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, which peaked at about 100,000 in 2011, is about 9,800, of which most are assigned to the 13,000-person NATO-led “Resolute Support Mission” (RSM) that trains, assists, and advises the ANDSF. About 2,000 of the U.S. contingent are involved in combat against Al Qaeda and other terrorist groups, including the Afghanistan branch of the Islamic State organization (ISIL-Khorasan), under “Operation Freedom’s Sentinel” (OFS). -

Extreme/Harsh Weather Weekly Situation Report, 1 February-12 March 2017

HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE PROGRAMME EXTREME/HARSH WEATHER WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT, 1 FEBRUARY-12 MARCH 2017 Highlights 33 affected provinces 8,209 affected families reported 553 houses completely destroyed 2,282 houses severely damaged 501 houses partially damaged 202 individual deaths 127 individuals injured 3,439 affected families verified following assessments 1,998 families assisted by IOM Distribution of relief items to avalanche-affected families in Badakhshan on 21 February. © IOM 2017 Situation Overview Extreme weather conditions, including avalanches, floods, and heavy snowfall have affected 33 provinces of Afghanistan as of 3 February 2017. Badakhshan and Nooristan provinces were severely hit by two avalanches, resulting in causalities and destruction of houses, followed by flash floods on 18 February that significantly impacted Herat, Zabul and Nimroz provinces. An estimated 8,209 families were reportedly affected across Afghanistan, with 202 deaths and 127 persons sustaining injuries across the country. The majority of the reported caseloads have been assessed, with a total 3,439 families in need of assistance, while the distribution of relief items is underway and expected to be completed by 15 March 2017. Snow and flash floods damaged major roads in Afghanistan, delaying assessments and the dispatching of relief assistance to affected families. Rescuers were unable to reach snow-hit districts in the north, northeast, central, central highland, west, and eastern regions. The majority of the highways and roads linking to various districts that were initially closed have since reopened; however, some roads to districts in Badakhshan, Nooristan, Daikundi, Bamyan and Paktika are still closed. IOM RESPONSE Northeast Region Badakhshan: At least 83 families were affected by avalanches triggered by heavy snowfall in Maimai district on 3 February 2017, with 15 persons killed and 27 wounded. -

Humanitarian Assistance Programme (Hap) Extreme/Harsh Weather Weekly Situation Report 03-12 February 2017

HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE PROGRAMME (HAP) EXTREME/HARSH WEATHER WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT 03-12 FEBRUARY 2017 Highlights 31 Affected provinces 2,359 Reported affected families 126 Houses completely destroyed 380 Houses severely damaged 87 Houses partially damaged 134 Individual deaths 63 Individuals injured 652 Verified affected families following assessments Dispatchment of relief items to affected families of Badakhshan on 08 February 2017 © IOM 2017 Situation Overview Extreme weather conditions, including avalanches, floods, and heavy snowfall affected 31 provinces of Afghanistan on 03 February 2017. Badakhshan and Nooristan provinces were severely hit by two avalanches, resulting in causalities and destruction of houses. An estimated 2,359 families were reportedly affected, with 134 deaths, and 63 persons sustaining injuries in various parts of the country. The snow wreaked havoc on major roads in Afghanistan, delaying assessments and dispatching of relief assistance to affected families and rescuers, who were unable to reach snow-hit districts in the north, northeast, central, central highland, and eastern regions, with numerous roads cut off. The majority of the highways that were initially closed have since reopened; however, some roads linking to various districts are still closed, and efforts are underway by district authorities to reopen the roads. IOM RESPONSE Northeast Region Badakhshan: At least 53 families were affected in Maimai district. 10 persons were killed and 12 were wounded in avalanches triggered by heavy snowfall on 03 February 2017. The bodies were recovered by a FOCUS Humanitarian Assistance rescue team aided by the local com- munity, while the injured were transferred to a safe area. The district is not accessible as the roads are closed due to heavy snowfall. -

The Informal Regulation of the Onion Market in Nangarhar, Afghanistan Working Paper 26 Giulia Minoia, Wamiqullah Mumatz and Adam Pain November 2014 About Us

Researching livelihoods and Afghanistan services affected by conflict Kabul Jalalabad The social life of the Nangarhar Pakistan onion: the informal regulation of the onion market in Nangarhar, Afghanistan Working Paper 26 Giulia Minoia, Wamiqullah Mumatz and Adam Pain November 2014 About us Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) aims to generate a stronger evidence base on how people make a living, educate their children, deal with illness and access other basic services in conflict-affected situations. Providing better access to basic services, social protection and support to livelihoods matters for the human welfare of people affected by conflict, the achievement of development targets such as the Millennium Development Goals and international efforts at peace- building and state-building. At the centre of SLRC’s research are three core themes, developed over the course of an intensive one- year inception phase: . State legitimacy: experiences, perceptions and expectations of the state and local governance in conflict-affected situations . State capacity: building effective states that deliver services and social protection in conflict- affected situations . Livelihood trajectories and economic activity under conflict The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) is the lead organisation. SLRC partners include the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) in Sri Lanka, Feinstein International Center (FIC, Tufts University), Focus1000 in Sierra Leone, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), -

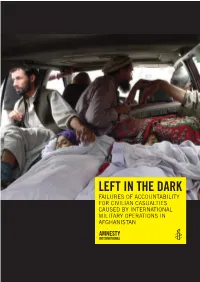

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

Afghanistan: Sikhs and Hindus

Country Policy and Information Note Afghanistan: Sikhs and Hindus Version 5.0 May 2019 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

Afghanistan Security Situation in Nangarhar Province

Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province Translation provided by the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Belgium. Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province LANDINFO – 13 OCTOBER 2016 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. © Landinfo 2017 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

Civilian Casualty Mitigation

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Civilian Casualty Mitigation Summary of Lessons, Observations and Tactics, Techniques and Procedures from Marine Expeditionary Brigade – Afghanistan (MEB-A) January – April 2010 Quick Look Report 29 July 2010 This Marine Corps Center for Lessons Learned (MCCLL) report provides an "initial impressions" summary identifying key observations or potential lessons from the collection effort. These observations are not service level opinions. Observations highlight potential shortfalls, risks or issues experienced by units that may suggest a need for institutional change or corrective action. The report is provided to DOTMLPF stakeholders and those who contribute to the Marine Corps fulfilling its statutory requirements. This unclassified document has been reviewed in accordance with guidance contained in United States Central Command Security Classification Regulation 380- 14 dated 13 January 2009. This document contains information EXEMPT FROM MANDATORY DISCLOSURE under the FOIA. DOD Regulation 5400.7R, Exemption 5 applies. - C. H. Sonntag, Director MCCLL. mccll/aal/v7_0 FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Executive Summary (U/FOUO) Purpose: To inform Deputy Commandants (DCs) Combat Development and Integration (CD&I), Plans, Programs, and Operations (PP&O), Commanding General (CG), Training and Education Command (TECOM), Director of Intelligence, operating forces and others on results of a January - April 2010 collection relating to mitigation of civilian casualties (CIVCAS). (U//FOUO) Background. Civilian casualties resulted from U.S. close air support in Farah, Afghanistan on 4 May 2009. In order to help prevent future instances of civilian casualties and mitigate their effects, U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM) requested that U.S. Joint Forces Command’s (USJFCOM) Joint Center for Operational Analysis (JCOA) capture lessons learned, and analyze incidents that led to coalition-caused civilian casualties during counterinsurgency (COIN) operations in Afghanistan. -

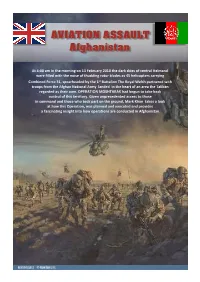

Moshtarak Pageplus Layout V2

AVIATION ASSAULT Afghanistan At 4:00 am in the morning on 13 February 2010 the dark skies of central Helmand were filled with the noise of thudding rotor blades as 45 helicopters carrying Combined Force 31, spearheaded by the 1st Battalion The Royal Welsh partnered with troops from the Afghan National Army landed in the heart of an area the Taliban regarded as their own. OPERATION MOSHTARAK had begun to take back control of this territory. Given unprecedented access to those in command and those who took part on the ground, Mark Khan takes a look at how this Operation, was planned and executed and provides a fascinating insight into how operations are conducted in Afghanistan. Aviation Assault - © Mark Khan 2015 As a result of the US presidential elections To allow larger operations to be conduct- The British contribution to the oper- In January 2009, the new US President ed under much more favourable condi- ation would be performed by 11 Barack Obama fulfilled his commitment, tions, preparatory work would be Light Brigade commanded by Briga- to significantly increase troop densities in carried out to “shape” the environment. dier James Cowan and would focus Afghanistan. This combined with the When conditions were then suitable, the on the central Helmand area. Two appointment of Lt Gen Stanley “clear” phase would take place with signif- specific insurgent strongholds were McChrystal, as the head of the icant military operations to push the in- chosen for the assault. international Security Assistance Force surgenOnce this phase had been These were known as “The Cha e (ISAF) in Afghanistan, led to a significant completed, the “hold” phase would take Angir Triangle” (a triangular area of change in strategy. -

The Readiness of Canada's Naval Forces Report of the Standing

The Readiness of Canada's Naval Forces Report of the Standing Committee on National Defence Stephen Fuhr Chair June 2017 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. For greater certainty, this permission does not affect the prohibition against impeaching or questioning the proceedings of the House of Commons in courts or otherwise. The House of Commons retains the right and privilege to find users in contempt of Parliament if a reproduction or use is not in accordance with this permission. -

Security Council Distr.: General 30 May 2018

United Nations S/2018/466 Security Council Distr.: General 30 May 2018 Original: English Letter dated 16 May 2018 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to transmit herewith the ninth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team established pursuant to resolution 1526 (2004), which was submitted to the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011), in accordance with paragraph (a) of the annex to resolution 2255 (2015). I should be grateful if the present letter and the report could be brought to the attention of the Security Council members and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Kairat Umarov Chair Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) 18-06956 (E) 050618 *1806956* S/2018/466 Letter dated 30 April 2018 from the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team addressed to the Chair of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) I have the honour to refer to paragraph (a) of the annex to Security Council resolution 2255 (2015), in which the Council requested the Monitoring Team to submit, in writing, two annual comprehensive, independent reports to the Committee, on implementation by Member States of the measures referred to in paragraph 1 of the resolution, including specific recommendations for improved implementation of the measures and possible new measures. I therefore transmit to you the ninth report of the Monitoring Team, pursuant to the above-mentioned request. The Monitoring Team notes that the original language of the report is English. -

Responding to the Next Attack

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point Objective • Relevant • Rigorous | May 2017 • Volume 10, Issue 5 FEATURE ARTICLE A VIEW FROM THE CT FOXHOLE Responding to the James Next Attack Gagliano Learning from the police response in Orlando and San Bernardino Former FBI Hostage Rescue Team Frank Straub, Jennifer Zeunik, and Ben Gorban Counterterrorist Operator FEATURE ARTICLE Editor in Chief 1 Lessons Learned from the Police Response to the San Bernardino and Orlando Terrorist Attacks Paul Cruickshank Frank Straub, Jennifer Zeunik, and Ben Gorban Managing Editor INTERVIEW Kristina Hummel 8 A View from the CT Foxhole: James A. Gagliano, Former FBI Hostage Rescue EDITORIAL BOARD Team Counterterrorist Operator Paul Cruickshank Colonel Suzanne Nielsen, Ph.D. Department Head ANALYSIS Dept. of Social Sciences (West Point) 13 A New Age of Terror? Older Fighters in the Caliphate Lieutenant Colonel Bryan Price, Ph.D. John Horgan, Mia Bloom, Chelsea Daymon, Wojciech Kaczkowski, Director, CTC and Hicham Tiflati 20 The Terror Threat to Italy: How Italian Exceptionalism is Rapidly Brian Dodwell Diminishing Deputy Director, CTC Michele Groppi 29 Iranian Kurdish Militias: Terrorist-Insurgents, Ethno Freedom Fighters, or CONTACT Knights on the Regional Chessboard? Combating Terrorism Center Franc Milburn U.S. Military Academy 607 Cullum Road, Lincoln Hall In the early hours of June 12, 2016, an Islamic State-inspired gunman car- West Point, NY 10996 ried out the deadliest terrorist attack on U.S. soil since 9/11, shooting dead 49 people in an Orlando nightclub. The attacker was finally killed after a Phone: (845) 938-8495 three-hour hostage standof, leading to questions raised in the media over the police response.