The Reappearing Oeuvre: Women's Art in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Do Ideas Come From?

Where do ideas come from? Where do ideas come from? 1 Where do ideas come from? At Deutsche Bank we surround ourselves with art. International contemporary art plays its part in helping us to navigate a changing world. As a global bank we want to understand, and engage with, different regions and cultures, which is why the Deutsche Bank Collection features contemporary artists from all over the globe. These artists connect us to their worlds. Art is displayed throughout our offices globally, challenging us to think differently, inviting us to look at the world through new eyes. Artists are innovators and they encourage us to innovate. Deutsche Bank has been involved in contemporary art since 1979 and the ‘ArtWorks’ concept is an integral part of our Corporate Citizenship programme. We offer employees, clients and the general public access to the collection and partner with museums, art fairs and other institutions to encourage emerging talent. Where do ideas come from? 2 Deutsche Bank reception area with artworks by Tony Cragg and Keith Tyson Art in London The art in our London offices reflects both our local and global presence. Art enriches and opens up new perspectives for people, helping to break down boundaries. The work of artists such as Cao Fei from China, Gabriel Orozco from Mexico, Wangechi Mutu from Kenya, Miwa Yanagi from Japan and Imran Qureshi from Pakistan, can be found alongside artists from the UK such as Anish Kapoor, Damien Hirst, Bridget Riley and Keith Tyson. We have named conference rooms and floors after these artists and many others. -

Sotheby's Sotheby's Contemporary Art Evening Sale Contemporary Art

Press Release London For Immediate Release London | +44 (0)20 7293 6000 | Matthew Weigman | [email protected] Simon Warren | [email protected] | Sotheby’s Contemporary Art Evening Sale Led bybyby Strong British Art Section Peter Doig’s Bellevarde of 1995 Estimate: £1.5£1.5––––22 million Sotheby’s forthcoming Contemporary Art Evening Auction on Thursday, October 13, 20112011, which coincides with London’s Frieze Art Fair, will be led by an exceptionally strong section of British Art that is highlighted by Lucian FreudFreud’s’s Boy’s Head of 1952. The British Art section also includes important pieces by Peter DoigDoig,,,, Frank AuerbachAuerbach, Leon KossoffKossoff, Marc Quinn and Glenn BrownBrown. The auction will also feature works by established greats such as Andy WarholWarhol, JeanJean----MichelMichel BasquiatBasquiat,, Miquel Barceló and SigmSigmarararar Polke as well as an offering of artworks by younger artists including Jacob KassayKassay. The 47-lot auction is estimated at in excess of £19 million. Discussing the forthcoming auction, Cheyenne Westphal, Sotheby’s Head of Contemporary Art Europe, commented: “Sotheby’s established the record for an auction of Contemporary Art staged in Europe with our Contemporary Art Evening Sale in London just three months ago, which is resounding testimony to the buoyancy of this market sector. The sale we have assembled this season features works by established titans such as Warhol and Basquiat, as well as art by the young and upcoming generation of artists such as Jacob Kassay. The focus of this year’s October Auction is our exceptionally strong offering of British Art, led by the outstanding portrait ‘Boy’s Head’ by Lucian Freud, an indisputable masterpiece by the great legend of the London School.” The sale will be headlined by Boy's Head of 1952 by Lucian Freud (1922-2011), depicting Charlie Lumley, one of Freud's most immediately recognisable subjects from this seminal early period in his oeuvre. -

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and Works in London, UK

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and works in London, UK Goldsmith's College, London, UK, 1988 Solo Exhibitions 2017 Michael Landy: Breaking News-Athens, Diplarios School presented by NEON, Athens, Greece 2016 Out Of Order, Tinguely Museum, Basel, Switzerland (Cat.) 2015 Breaking News, Michael Landy Studio, London, UK Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2014 Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico 2013 20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK (Cat.) Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2011 Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 2010 Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK 2009 Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France 2008 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Three-piece, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2007 Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (Cat.) H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA (Cat.) 2004 Welcome To My World-built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK (Cat.) 2003 Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany 2002 Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK 2001 Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, Artangel Commission, London, UK (Cat.) 2000 Handjobs (with Gillian -

Lucy Sparrow Photo: Dafydd Jones 18 Hot &Coolart

FREE 18 HOT & COOL ART YOU NEVER FELT LUCY SPARROW LIKE THIS BEFORE DAFYDD JONES PHOTO: LUCY SPARROW GALLERIES ONE, TWO & THREE THE FUTURE CAN WAIT OCT LONDON’S NEW WAVE ARTISTS PROGRAMME curated by Zavier Ellis & Simon Rumley 13 – 17 OCT - VIP PREVIEW 12 OCT 6 - 9pm GALLERY ONE PETER DENCH DENCH DOES DALLAS 20 OCT - 7 NOV GALLERY TWO MARGUERITE HORNER CARS AND STREETS 20 - 30 OCT GALLERY ONE RUSSELL BAKER ICE 10 NOV – 22 DEC GALLERY TWO NEIL LIBBERT UNSEEN PORTRAITS 1958-1998 10 NOV – 22 DEC A NEW NOT-FOR-PROFIT LONDON EXHIBITION PLATFORM SUPPORTING THE FUSION OF ART, PHOTOGRAPHY & CULTURE Art Bermondsey Project Space, 183-185 Bermondsey Street London SE1 3UW Telephone 0203 441 5858 Email [email protected] MODERN BRITISH & CONTEMPORARY ART 20—24 January 2016 Business Design Centre Islington, London N1 Book Tickets londonartfair.co.uk F22_Artwork_FINAL.indd 1 09/09/2015 15:11 THE MAYOR GALLERY FORTHCOMING 21 CORK STREET, FIRST FLOOR, LONDON W1S 3LZ TEL: +44 (0) 20 7734 3558 FAX: +44 (0) 20 7494 1377 [email protected] www.mayorgallery.com EXHIBITIONS WIFREDO ARCAY CUBAN STRUCTURES THE MAYOR GALLERY 13 OCT - 20 NOV Wifredo Arcay (b. 1925, Cuba - d. 1997, France) “ETNAIRAV” 1959 Latex paint on plywood relief 90 x 82 x 8 cm 35 1/2 x 32 1/4 x 3 1/8 inches WOJCIECH FANGOR WORKS FROM THE 1960s FRIEZE MASTERS, D12 14 - 18 OCT Wojciech Fangor (b.1922, Poland) No. 15 1963 Oil on canvas 99 x 99 cm 39 x 39 inches STATE_OCT15.indd 1 03/09/2015 15:55 CAPTURED BY DAFYDD JONES i SPY [email protected] EWAN MCGREGOR EVE MAVRAKIS & Friend NICK LAIRD ZADIE SMITH GRAHAM NORTON ELENA SHCHUKINA ALESSANDRO GRASSINI-GRIMALDI SILVIA BRUTTINI VANESSA ARELLE YINKA SHONIBARE NIMROD KAMER HENRY HUDSON PHILIP COLBERT SANTA PASTERA IZABELLA ANDERSSON POPPY DELEVIGNE ALEXA CHUNG EMILIA FOX KARINA BURMAN SOPHIE DAHL LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE CHIWETEL EJIOFOR EVGENY LEBEDEV MARC QUINN KENSINGTON GARDENS Serpentine Gallery summer party co-hosted by Christopher Kane. -

Specified Artist: Marc Quinn (B. 1964) Teaching and Learning

Specified Artist: Marc Quinn (b. 1964) 1964 Born in London. 1983 First learned to cast in bronze, while working as an assistant to Barry Flanagan. 1986 Graduated from Cambridge University (History & History of Art). 1988 First solo show at Jay Jopling/Otis Gallery, London. 1991 SELF 1992 Selected for the Sydney Biennale. 1993 Participated in Young British Artists II at Saatchi Gallery. 1994 Participated in Time Machine at British Museum. 1996 Participated in Thinking Print at MoMA, New York. 1997 Participated in Sensation at Royal Academy, London. 1998 Solo show at South London Gallery, Camberwell, London. 2002 Solo exhibition Tate Liverpool and participated in Liverpool Biennale. 2005-7 ALISON LAPPER PREGNANT, first commission for Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square, London 2008 SIREN 2012 BREATH London Paralympic Games 2013 Solo exhibition Venice Biennale 2017 Solo exhibition John Soane Museum, London Teaching and learning: Example No. 1 Self, series begun 1991: Personal Identity Genre: Self-portraiture: choices and effects Location: 2006 Version in National Portrait Gallery – sits alongside national heroes and leaders…. Art History in Schools CIO | Registered Charity No. 1164651 | www.arthistoryinschools.org.uk Materials, techniques and processes: innovation and consequences Style: YBA, influences of other artists Patronage: role of Saatchi…. Activity 1: Exploring Self-portraiture Find images of four versions of Self and arrange in chronological order. Then research the self-portraits of Rembrandt, Vincent Van Gogh and Frida Kahlo. Select four of each and add them to your image sheet. Explore/explain what you see as the changing perceptions, perspectives or significant factors between the three artists. • Now research their lives. -

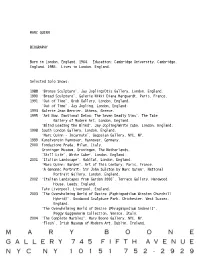

Quinn Biography

MARC QUINN BIOGRAPHY Born in London, England, 1964. Education: Cambridge University, Cambridge, England, 1985. Lives in London, England. Selected Solo Shows: 1988 “Bronze Sculpture”, Jay Jopling/Otis Gallery, London, England. 1990 “Bread Sculpture”, Galerie Nikki Diana Marquardt, Paris, France. 1991 “Out of Time”, Grob Gallery, London, England. “Out of Time”, Jay Jopling, London, England. 1993 Galerie Jean Bernier, Athens, Greece. 1995 “Art Now. Emotional Detox: The Seven Deadly Sins”, The Tate Gallery of Modern Art, London, England. “Blind Leading the Blind”, Jay Jopling/White Cube, London, England. 1998 South London Gallery, London, England. “Marc Quinn – Incarnate”, Gagosian Gallery, NYC, NY. 1999 Kunstverein Hannover, Hannover, Germany. 2000 Fondazione Prada, Milan, Italy. Groninger Museum, Groningen, The Netherlands. “Still Life”, White Cube², London, England. 2001 “Italian Landscape”, Habitat, London, England. “Marc Quinn: Garden”, Art of This Century, Paris, France. “A Genomic Portrait: Sir John Sulston by Marc Quinn”, National Portrait Gallery, London, England. 2002 “Italian Landscapes from Garden 2000”, Terrace Gallery, Harewood House, Leeds, England. Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, England. 2003 “The Overwhelming World of Desire (Paphiopedilum Winston Churchill Hybrid)”, Goodwood Sculpture Park, Chichester, West Sussex, England. “The Overwhelming World of Desire (Phragmipedium Sedenii)”, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, Italy. 2004 “The Complete Marbles”, Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. “Flesh”, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland. MARC QUINN BIOGRAPHY (continued) : Selected Solo Shows: 2005 “Flesh”, Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. “Chemical Life Support”, White Cube, London, England. “Alison Lapper Pregnant”, Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square, London, England. 2006 “Marc Quinn: Recent Sculptures”, Groninger Museum, Groningen, The Netherlands. Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Roma, Rome, Italy. 2007 “Sphinx”, Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. -

The FLAG Art Foundation Presents New Exhibition: “Attention To

The FLAG Art Foundation Pre sents New Exhibition: “Attention to Detail” The FLAG Art Foundation is pleased to announce its inaugural ex hibition, "Attention to Detail." Curated by renowned contemporary artist Chuck Close, the show includes work from a wide range of both established and emerging artists: Louise Bourgeois Brice Marden Delia Brown Tony Matelli Glenn Brown Ron Mueck Maurizio Cattelan Richard Patterson Vija Celmins Richard Pettibone Jennifer Dalton Elizabeth Peyton Thomas Demand Richard Phillips Tara Donovan Marc Quinn Olafur Eliasson Alessandro Raho Dan Fischer Gerhard Richter Tom Friedman Aaron Romine Ellen Gallagher Ed Ruscha Tim Gardner Cindy Sherman Franz Gertsch James Siena Ewan Gibbs Ken Solomon Robert Gober Thomas Struth Andreas Gursky Tomoaki Suzuki Damien Hirst Yuken Teruya Jim Hodges Fred Tomaselli Naoto Kawahara Jim Torok Ellsworth Kelly Mark Wagner Cary Kwok Rachel Whiteread Robert Lazzarini Fred Wilson Graham Little Steve Wolfe Christian Marclay Lisa Yuskavage Whether it is through conceptual or technical precision, the deceptively lifelik e nature of a hand-crafted image, a playful interpretation or distortion of a familiar object or the detailed appropriation of another artist's work, an acute focus on the minute connects these works and these artists’ approaches. These artists demonstrate a labor-intensive and exacting artistic passion in their respective processes. As Chuck Close fittingly reflects with respect to his own work, "I am going for a level of perfection that is only mine...Most of the pleas ure is in getting the last little piece perfect." Chuck Close (b. 1940, Monroe, WA) received his B.A. from the University of Washington, Seattle before studying at Yale University School of Art and Architecture (B.F.A., 1963; M.F.A. -

Contemporary Art from the Richard Brown Baker Collection September 23, 2011-January 8, 2012

Made in the UK: Contemporary Art from the Richard Brown Baker Collection September 23, 2011-January 8, 2012 Made in the UK offers an exceptional look at developments in British art--from the abstract painting of the 1950s to the hyperrealist images of the 1970s to the varied approaches of contemporary work. Throughout this period British art has been integral to international developments in contemporary art, but many of the artists included in this exhibition are less well known in America today than they once were. The RISD Museum's extraordinary collection of postwar British art-- uniquely strong in the United States--was made possible by the foresight and generosity of renowned collector Richard Brown Baker (American, 1912--2002). The show celebrates his extraordinary gift of British art as well as the works purchased with the substantial bequest he provided to continue building the collection. Baker, a Providence native, moved to New York in 1952, living just blocks from the 57th Street art galleries. As the city evolved into the new center of the art world, Baker was compelled to collect. Although he did not have large funds at his disposal, he became one of the most prescient collectors of American and European contemporary art in the late 20th century, acquiring more than 1,600 works, many before the artists had established their reputations. Baker never intended to build a collection of British art; his British holdings developed naturally in the context of his international outlook. He gave most of his collection to the Yale University Art Gallery, his alma mater, but gifted the RISD Museum more than 300 works, of which 136 are British. -

Marc Quinn (British, B. 1964) – Artist Resources Quinn’S Website: Artwork, Interviews, Exhibition History

Marc Quinn (British, b. 1964) – Artist Resources Quinn’s website: artwork, interviews, exhibition history In 2014 video interview with the “In Your Face” series by SHOWstudio, Quinn explains “I start with an idea, but it always transforms during the creation…an idea is a beginning of a journey and the final artwork is the end of a journey, or the beginning of another journey, the journey of interpretation.” Quinn eschews the moniker of artist and describes himself as “just a chronicler,” in a 2015 profile by the New York Times. “I want my work to be about what it means to be a person living now.” Quinn discusses his approach to art as activism in a brief interview with GQ Magazine: “Part of our job as artists is to reflect the times we live in…[not] to just organize a charity auction or donate a piece of work. I wanted to make something, something that, while being an important artwork, might actually help change the condition of that topic in the real world.” Tate Britain’s 2015 exhibition, Emotional Detox showcased lead Quinn, 2005 sculptures cast by Quinn from his own body, exploring the pathways Photograph: Clive Arrowsmith and struggles of physical and psychological detox through iconography inspired by the seven deadly sins. Review of 2015 exhibition, The Toxic SuBlime, in which Quinn explored the “the exploitative relationship between humans and nature.” In 2019, Quinn participated in his first solo exhibition in China, at the Central Academy of Fine Art Museum (CAFA) in Beijing. The show brought together significant works throughout Quinn’s 30-year career, exploring his interest in identity and his affinity for unexpected materials. -

Glenn Brown in Conversation with Mardee Goff

A conversation between Glenn Brown and Mardee Goff, one of the curators of ‘Portrait of the Artist As…’ recorded at Brown’s studio in East London on 7 June 2012. The artist generally prefers written interviews but graciously agreed to this informal conversation in which he discusses his work ‘Decline and Fall’. What emerges is a representation of the artist’s personality in keeping with the spirit of the exhibition. MG: When looking at an early work like Decline and Fall, how has it changed over time for you? Does it seem different from your work now? GB: The sensation I often get when looking at earlier work is that I don’t think that I could paint like that now. I think the way I paint is quite different now. The paintings then were much smaller and tighter. Now they tend to be bigger and slightly looser. There is an intensity in earlier work that I don’t think I could reproduce. Well I could, but I don’t think I would want too, and certainly Decline and Fall fits into this category. MG: As you say this canvas is smaller than many of your works now. Was this to do at all with the studio you were working in at the time? Or was it just what you chose to take on? GB: As far as I remember the size of the canvas is the size of the original Auerbach canvas, even though my painting has been quite heavily cropped. So you don’t actually see all the painting, and in some senses the brush stokes have been enlarged. -

Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument Contemporary 5 Dec 2012— 20 Jan 2013 Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument Contemporary

5 Dec 2012— 20 Jan 2013 Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument 5 Dec 2012— 20 Jan 2013 Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument Foreword The Mayor of London's Fourth Plinth has always been a space for experimentation in contemporary art. It is therefore extremely fitting for this exciting exhibition to be opening at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London – an institution with a like-minded vision that continues to champion radical and pioneering art. This innovative and thought-provoking programme has generated worldwide appeal. It has provided both the impetus and a platform for some of London’s most iconic artworks and has brought out the art critic in everyone – even our taxi drivers. Bringing together all twenty-one proposals for the first time, and exhibiting them in close proximity to Trafalgar Square, this exhibition presents an opportunity to see behind the scenes, not only of the Fourth Plinth but, more broadly, of the processes behind commissioning contemporary art. It has been a truly fascinating experience to view all the maquettes side-by-side in one space, to reflect on thirteen years’ worth of work and ideas, and to think of all the changes that have occurred over this period: changes in artistic practice, the city’s government, the growing heat of public debate surrounding national identity and how we are represented through the objects chosen to adorn our public spaces. The triumph of the Fourth Plinth is that it ignites discussion among those who would not usually find themselves considering the finer points of contemporary art. We very much hope this exhibition will continue to stimulate debate and we encourage you to tell us what you think at: www.london.gov.uk/fourthplinth Justine Simons Head of Culture for the Mayor of London Gregor Muir Executive Director, ICA 2 3 5 Dec 2012— 20 Jan 2013 Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument One Thing Leads To Another… Michaela Crimmin Trafalgar Square holds interesting tensions. -

Portrait/Icon/Code: Marc Quinn's Dna Portraits

PORTRAIT/ICON/CODE: MARC QUINN’S DNA PORTRAITS AND THE IMAGING OF THE SELF by BRIGETTE N. THOMAS (Under the Direction of Isabelle Loring Wallace) ABSTRACT In 2001, Marc Quinn was commissioned to create a portrait of Sir John Edward Sulston for the National Portrait Gallery of London. The resulting portrait, a framed plate of cloned DNA, looks unlike any other portrait in the gallery. This portrait and two subsequent DNA portraits appear at first to be critical of both portraiture and DNA science. However, a careful analysis of these works and the traditions of art which they reference – those of portraiture, self portraiture, and icons - show these to be studies in the history of the image and the ways in which the human relationship with the image can be seen to move in a cyclical, rather than linear fashion. While DNA may be a new medium, Quinn points out that the fears and fantasies inspired by DNA science are both timeless and timely, stemming from enduring anxieties about the image. INDEX WORDS: Marc Quinn, Portraiture, Self-Portraiture, Icons, Subjectivity, Bio-Art, DNA, Genetics, Cloning PORTRAIT/ICON/CODE: MARC QUINN’S DNA PORTRAITS AND THE IMAGING OF THE SELF by BRIGETTE N. THOMAS B.A., West Virginia Wesleyan College, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Brigette N. Thomas All Rights Reserved PORTRAIT/ICON/CODE: MARC QUINN’S DNA PORTRAITS AND THE IMAGING OF THE SELF by BRIGETTE N.