A Journey from Understanding Culturally Responsive Teaching to Identifying As Culturally Responsive Teachers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isleno Decima Singers of Louisiana

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2002 Isleno Decima Singers of Louisiana: an interpretation of performance and event Danielle Elise Sears Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Sears, Danielle Elise, "Isleno Decima Singers of Louisiana: an interpretation of performance and event" (2002). LSU Master's Theses. 342. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/342 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISLENO DECIMA SINGERS OF LOUISIANA: AN INTERPRETATION OF PERFORMANCE AND EVENT A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In The Department of Communication Studies by Danielle Elise Sears B.G.S., Louisiana State University, 1996 December, 2002 Acknowledgments To the many people in the Department of Communication Studies who have enthusiastically guided me along the way, I give my appreciation and gratitude. I am ever indebted to Dr. Michael Bowman whose mentorship, patience, time and friendship guided me throughout this study. I would also like to thank Dr. Ruth Bowman and Dr. Patricia Suchy for their never ending words of encouragement and votes of confidence. -

September 20, 2000 Issue 3

Volume 50 September 20, 2000 issue 3 World View: Ford New head coach and Firestone take leads TSU Tigers to more legal heat over Memphis... and v safety mishaps almost to victory Tiennessee St:ate "University ^ A" Page S Page 19 THc 2%^casz€rc ofStude^rrt Ojyinion. and Sontiment Freshman Elections give new arrivals jSACS study says a voice in TSU student government graduate programs, are Jessica Bell as Miss By Crystal McMoore Freshman, Charles .1. faculty, library need Ne-ws Writer Galbreath and Rickenya Goodson as freshman The freshman class now has newly elected offi representatives, and most improvement cials to give it a voicein student government. Leading Ashley Smith as the new the class is Timothy E. "Big Red" Mitchell,who was vice president. TSU won't be re-accredited elected president of the class of 2004 by a landslide The election is an vote in a very light voter turnout. important element of until gains made from Among the other winners in this year's elections each academic year, but often it is not a well- recognized custom SACS and TSU's self-study by the members of PHOTO COURTESY OF CHARLES Freshioian Class Officers GALBREATH the freshman class. Freshman Qass 'resident Timothy E. Mitch3K There are a jBy Kester Kilkenny Representative Charles reported 4,431 ^News Editor entering freshmen Galbreath, Jr, icePresident llAshley Smith this year, and fewer Tennessee State University meets the majority of than 200 voted. rei^uirements for its effort to be re-accredited, but there arc About 30 people, including those running, several major weaknesses, according to TSU's self-.study Alicia Robinson attended a debate among the candidates running ^report published on its Web site and astudy by the Southern foi" office. -

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017 Researched, compiled, and calculated by Lance Mangham Contents • Sources • The Top 100 of All-Time • The Top 100 of Each Year (2017-1956) • The Top 50 of 1955 • The Top 40 of 1954 • The Top 20 of Each Year (1953-1930) • The Top 10 of Each Year (1929-1900) SOURCES FOR YEARLY RANKINGS iHeart Radio Top 50 2018 AT 40 (Vince revision) 1989-1970 Billboard AC 2018 Record World/Music Vendor Billboard Adult Pop Songs 2018 (Barry Kowal) 1981-1955 AT 40 (Barry Kowal) 2018-2009 WABC 1981-1961 Hits 1 2018-2017 Randy Price (Billboard/Cashbox) 1979-1970 Billboard Pop Songs 2018-2008 Ranking the 70s 1979-1970 Billboard Radio Songs 2018-2006 Record World 1979-1970 Mediabase Hot AC 2018-2006 Billboard Top 40 (Barry Kowal) 1969-1955 Mediabase AC 2018-2006 Ranking the 60s 1969-1960 Pop Radio Top 20 HAC 2018-2005 Great American Songbook 1969-1968, Mediabase Top 40 2018-2000 1961-1940 American Top 40 2018-1998 The Elvis Era 1963-1956 Rock On The Net 2018-1980 Gilbert & Theroux 1963-1956 Pop Radio Top 20 2018-1941 Hit Parade 1955-1954 Mediabase Powerplay 2017-2016 Billboard Disc Jockey 1953-1950, Apple Top Selling Songs 2017-2016 1948-1947 Mediabase Big Picture 2017-2015 Billboard Jukebox 1953-1949 Radio & Records (Barry Kowal) 2008-1974 Billboard Sales 1953-1946 TSort 2008-1900 Cashbox (Barry Kowal) 1953-1945 Radio & Records CHR/T40/Pop 2007-2001, Hit Parade (Barry Kowal) 1953-1935 1995-1974 Billboard Disc Jockey (BK) 1949, Radio & Records Hot AC 2005-1996 1946-1945 Radio & Records AC 2005-1996 Billboard Jukebox -

Jukebox Decades – 100 Hits Ultimate Soul

JUKEBOX DECADES – 100 HITS ULTIMATE SOUL Disc One - Title Artist Disc Two - Title Artist 01 Ain’t No Sunshine Bill Withers 01 Be My Baby The Ronettes 02 How ‘Bout Us Champaign 02 Captain Of Your Ship Reparata 03 Sexual Healing Marvin Gaye 03 Band Of Gold Freda Payne 04 Me & Mrs. Jones Billy Paul 04 Midnight Train To Georgia Gladys Knight 05 If You Don’t Know Me Harold Melvin 05 Piece of My Heart Erma Franklin 06 Turn Off The Lights Teddy Pendergrass 06 Woman In Love The Three Degrees 07 A Little Bit Of Something Little Richard 07 I Need Your Love So Desperately Peaches 08 Tears On My Pillow Johnny Nash 08 I’ll Never Love This Way Again D Warwick 09 Cause You’re Mine Vibrations 09 Do What You Gotta Do Nina Simone 10 So Amazing Luther Vandross 10 Mockingbird Aretha Franklin 11 You’re More Than A Number The Drifters 11 That’s What Friends Are For D Williams 12 Hold Back The Night The Tramps 12 All My Lovin’ Cheryl Lynn 13 Let Love Come Between Us James 13 From His Woman To You Barbara Mason 14 After The Love Has Gone Earth Wind & Fire 14 Personally Jackie Moore 15 Mind Blowing Decisions Heatwave 15 Every Night Phoebe Snow 16 Brandy The O’ Jays 16 Saturday Love Cherrelle 17 Just Be Good To Me The S.O.S Band 17 I Need You Pointer Sisters 18 Ready Or Not Here I The Delfonics 18 Are You Lonely For Me Freddie Scott 19 Home Is Where The Heart Is B Womack 19 People The Tymes 20 Birth The Peddlers 20 Don’t Walk Away General Johnson Disc Three - Title Artist Disc Four - Title Artist 01 Till Tomorrow Marvin Gaye 01 Lean On Me Bill Withers 02 Here -

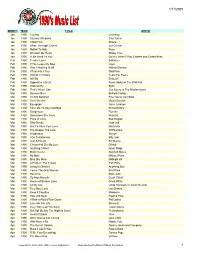

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

Title Artist Gangnam Style Psy Thunderstruck AC /DC Crazy In

Title Artist Gangnam Style Psy Thunderstruck AC /DC Crazy In Love Beyonce BoomBoom Pow Black Eyed Peas Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Old Time Rock n Roll Bob Seger Forever Chris Brown All I do is win DJ Keo Im shipping up to Boston Dropkick Murphy Now that we found love Heavy D and the Boyz Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande and Nicki Manaj Let's get loud J Lo Celebration Kool and the gang Turn Down For What Lil Jon I'm Sexy & I Know It LMFAO Party rock anthem LMFAO Sugar Maroon 5 Animals Martin Garrix Stolen Dance Micky Chance Say Hey (I Love You) Michael Franti and Spearhead Lean On Major Lazer & DJ Snake This will be (an everlasting love) Natalie Cole OMI Cheerleader (Felix Jaehn Remix) Usher OMG Good Life One Republic Tonight is the night OUTASIGHT Don't Stop The Party Pitbull & TJR Time of Our Lives Pitbull and Ne-Yo Get The Party Started Pink Never Gonna give you up Rick Astley Watch Me Silento We Are Family Sister Sledge Bring Em Out T.I. I gotta feeling The Black Eyed Peas Glad you Came The Wanted Beautiful day U2 Viva la vida Coldplay Friends in low places Garth Brooks One more time Daft Punk We found Love Rihanna Where have you been Rihanna Let's go Calvin Harris ft Ne-yo Shut Up And Dance Walk The Moon Blame Calvin Harris Feat John Newman Rather Be Clean Bandit Feat Jess Glynne All About That Bass Megan Trainor Dear Future Husband Megan Trainor Happy Pharrel Williams Can't Feel My Face The Weeknd Work Rihanna My House Flo-Rida Adventure Of A Lifetime Coldplay Cake By The Ocean DNCE Real Love Clean Bandit & Jess Glynne Be Right There Diplo & Sleepy Tom Where Are You Now Justin Bieber & Jack Ü Walking On A Dream Empire Of The Sun Renegades X Ambassadors Hotline Bling Drake Summer Calvin Harris Feel So Close Calvin Harris Love Never Felt So Good Michael Jackson & Justin Timberlake Counting Stars One Republic Can’t Hold Us Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Ft. -

DJ Master Mix CD List

DJ Master Mix CD List ***Background Music*** 25 Gloria in Excelsis Deo (vocal) 2 Pennsylvania 6-5000 3 Chatanooga Choo-Choo 101 Strings Play Frank Sinatra ***Background Music*** 4 String of pearls 1 All the way 25 All Time Christmas Favorites Di 5 In the mood 2 Strangers in the night 1 Jingle bells (pop) 6 Sunrise serenade 3 Fly me to the moon 2 Joy to the world (pop) 7 Johnson rag 4 New York, New York 3 Deck the halls (pop) 8 American patrol 5 The lady is a tramp 4 We wish you a merry Christmas (pop) 9 Kalamazoo 6 Come fly with me 5 Hark the herald angels sing (pop) 10 Bugle call rag 7 I've got you under my skin 6 Jolly old St. Nicholas (pop) 11 Anvil chorus 8 Young at heart 7 O Christmas Tree (pop) 12 Tuxedo junction 9 Just the way you look tonight 8 Auld Lang Syne (pop) 13 Moonlight cocktail 10 You're nobody till somebody loves you 9 The twelve days of Christmas(pop) 14 Serenade in blue 11 The shadow of your smile 10 We three Kings (pop) 12 Three coins in the fountain 11 Ave Maria (vocal) ***Background Music*** ***Background Music*** 12 Gloria a Jesu(vocal) Big Band Spectacular Vol. II 13 Alleluia (vocal) 1 One O'clock jump 15 of the World's Greatest Love Son 14 II Est Ne Le Divin Enfant 2 Jersey bounce 1 Wind beneath my wings 15 Silver Bells (vocal) 3 Frankie and Johnny were lovers 2 Always on my mind 16 Alleluiah 4 Stomping at the Savoy 3 All out of love 17 For unto us a child is born 5 Down south camp meeting 4 Dust in the wind 18 The trumpet shall sound 6 Jumping at the woodside 5 Lady in red 19 Amen 7 Let's dance 6 Up where we -

Art and Social Change a Critical Reader

ART AND SOCIAL CHANGE A CRITICAL READER EDITED BY WILL BRADLEY AND CHARLES ESCHE TATE PUBLISHING IN ASSOCIATION WITH AFTERALL First published 2007 by order of the Tate Trustees by Tate Publishing, a division of Tate Enterprises Ltd Millbank, London sw1p 4rg www.tate.org.uk/publishing In association with Afterall Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design, University of the Arts London 107–109 Charing Cross Road London wc2h 0du Copyright © Tate, Afterall 2007 Individual contributions © the authors 2007 unless otherwise specified Artworks © the artists or their estates unless otherwise specified All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-85437-626-8 Distributed in the United States and Canada by Harry N. Abrams Inc., New York Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Library of Congress Control Number: 2007934790 Designed by Kaisa Lassinaro, Sara De Bondt Printed by Graphicom SPA, Italy CONTENTS 99 Deutschland Deutschland Über Alles Kurt Tucholsky and John Heartfield Preface [7] Charles Esche 104 Bauhaus no.3, The Students Voice Kostufra Introduction [9] Will Bradley 106 The Fall of Hannes Meyer Kostufra Colour plates [25] 108 Letter, August 1936 PART I – 1871 Felicia Browne 36 Letters, October 1870–April 1871 110 We Ask Your Attention Gustave Courbet British Surrealist Group 29 October 1870 18 March 1871 115 Vision in Motion 7 April 1871 László Moholy-Nagy 30 April 1871 PART III – 1968 40 Socialism from the Root Up William Morris and E. -

Artist Song Album Blue Collar Down to the Line Four Wheel Drive

Artist Song Album (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Blue Collar Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Down To The Line Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Four Wheel Drive Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Free Wheelin' Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Gimme Your Money Please Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Hey You Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Lookin' Out For #1 Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Roll On Down The Highway Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Take It Like A Man Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Hits of 1974 (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet Hits of 1974 (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. Blue Sky Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Rockaria Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Showdown Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Strange Magic Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Sweet Talkin' Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Telephone Line Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Turn To Stone Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. -

Boyz II Men Twenty Itunes Deluxe Edition 2011

Boyz II Men - Twenty (iTunes Deluxe Edition) (2011) 1 / 4 Boyz II Men - Twenty (iTunes Deluxe Edition) (2011) 2 / 4 3 / 4 Boyz II Men - Twenty (iTunes Deluxe Edition) (2011) ->>->>->> http://shorl.com/miselugedybi download.Boyz.II.Men...Lil.Jon.And.The.East.Side.Boyz.-.Crunkest.. In 2011, Boyz II Men marked their 20th anniversary by releasing a landmark album, fittingly titled Twenty. The album contains the group's first original material in .... Preview, buy, and download songs from the album Twenty, including "Believe", "So Amazing", "Put Some Music On" and many more. Buy .the album for USD .... َََTwenty [iTunes Deluxe Edition] 2CD Boyz-II-Men-Twenty.jpg Master Q @ 128 Kbps Tracklist CD1 1 Believe 2. So Amazing 3. Put Some Music On 4. Slowly 5.. Cooleyhighharmony (1991) Please Don't Go, Lonely Heart, This Is My Heart, Uhh Ahh, It's So Hard.... According to no less an authority than the RIAA, Boyz II Men are the most commercially ... Legacy: The Greatest Hits Collection (Deluxe Edition) 1991 · I'll ... 2014. Twenty. 2011. Love ((Bonus Track Edition)). 2009. Throwback.. Album · 2001 · 32 Songs. Available with an Apple ... Legacy: The Greatest Hits Collection (Deluxe Edition) Boyz II Men · R&B/Soul; 2001 ... In the Still of the Nite (I'll Remember). 2:49. 5. Hey Lover ... Also Available in iTunes ... Motown - A Journey Through Hitsville USA. 2007. Twenty. 2011. Love (Bonus .... Complete list of Boyz II Men music featured in tv shows and movies. See scene ... Boyz II Men perform an accapella version at the end of the episode. Fresh Off the .. -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Luke I Wanna Rock 4:23 Luke - Greatest Hits 8 1996 Rap 128 Disk Local 2 Angie Stone No More Rain (In this Cloud) 4:42 Black Diamond 1999 Soul 3 128 Disk Local 3 Keith Sweat Merry Go Round 5:17 I'll Give All My Love to You 4 1990 RnB 128 Disk Local 4 D'Angelo Brown Sugar (Live) 10:42 Brown Sugar 1 1995 Soul 128 Disk Grand Verbalizer, What Time Is Local 5 X Clan 4:45 To the East Blackwards 2 1990 Rap 128 It? Disk Local 6 Gerald Levert Answering Service 5:25 Groove on 5 1994 RnB 128 Disk Eddie Local 7 Intimate Friends 5:54 Vintage 78 13 1998 Soul 4 128 Kendricks Disk Houston Local 8 Talk of the Town 6:58 Jazz for a Rainy Afternoon 6 1998 Jazz 3 128 Person Disk Local 9 Ice Cube X-Bitches 4:58 War & Peace, Vol.1 15 1998 Rap 128 Disk Just Because God Said It (Part Local 10 LaShun Pace 9:37 Just Because God Said It 2 1998 Gospel 128 I) Disk Local 11 Mary J Blige Love No Limit (Remix) 3:43 What's The 411- Remix 9 1992 RnB 3 128 Disk Canton Living the Dream: Live in Local 12 I M 5:23 1997 Gospel 128 Spirituals Wash Disk Whitehead Local 13 Just A Touch Of Love 5:12 Serious 7 1994 Soul 3 128 Bros Disk Local 14 Mary J Blige Reminisce 5:24 What's the 411 2 1992 RnB 128 Disk Local 15 Tony Toni Tone I Couldn't Keep It To Myself 5:10 Sons of Soul 8 1993 Soul 128 Disk Local 16 Xscape Can't Hang 3:45 Off the Hook 4 1995 RnB 3 128 Disk C&C Music Things That Make You Go Local 17 5:21 Unknown 3 1990 Rap 128 Factory Hmmm Disk Local 18 Total Sittin' At Home (Remix) -

Charley's Aunt," March 13-14 by AMY GOODRICH Guardian

Volume XX #8 Des Moines Area Community College-Boone Campus Mar. 11,1992 Drama Dept. presents "Charley's Aunt," March 13-14 By AMY GOODRICH guardian. Trouble, along wi~hmuch Staff Writer comedy, occur when the real aunt arrives. Boone DMACC's spring play is The exciting end of the play reve- off and running full speed ahead with als who ends up with whom, but you nothing in its way-xcept for must see for yourself on either maybe some smart alccky oneliners, Friday. March 13 or on Saturday, but no play would be complete with- March 14 at 8 p.m. in the auditorium. out those! This year's production is Here are some comments and titled "Charley's Aunt" and the char- background information about the acters of this play are not only witty characters in their own words and Britts, but are also quite unique. how they feel about this year's spring The play consists of Jack Chesney play: and Charles (Charley) Wykeham Brett Landon, plays the role of who are currently undergraduates at Jack Chesncy: "Mr. Jack Chesney is St. Olde's College, Oxford. These the driving force behind the play. He two charming men meet and fall is just an average guy with a little witt madly in love with Kitty Verdun and and charm. He is coinposed until he Amy Spettigue who are never allow- sees or thinks of Kitty Verdun, his ed to go anywhere without the driving force. Come see the play-it consent of their over-protective will be a great show!" Uncle Spettigue.