February 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLGICAL SECTION of the DEVONSHIRE ASSOCIATION Issue 5 April 2019 CONTENTS

INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLGICAL SECTION of the DEVONSHIRE ASSOCIATION Issue 5 April 2019 CONTENTS DATES FOR YOUR DIARY – forthcoming events Page 2 THE HEALTH OF TAMAR VALLEY MINE WORKERS 4 A report on a talk given by Rick Stewart 50TH SWWERIA CONFERENCE 2019 5 A report on the event THE WHETSTONE INDUSTRY & BLACKBOROUGH GEOLOGY 7 A report on a field trip 19th CENTURY BRIDGES ON THE TORRIDGE 8 A report on a talk given by Prof. Bill Harvey & a visit to SS Freshspring PLANNING A FIELD TRIP AND HAVING A ‘JOLLY’ 10 Preparing a visit to Luxulyan Valley IASDA / SIAS VISIT TO LUXULYAN VALLEY & BEYOND 15 What’s been planned and booking details HOW TO CHECK FOR NEW ADDITIONS TO LOCAL ARCHIVES 18 An ‘Idiots Guide’ to accessing digitized archives MORE IMAGES OF RESCUING A DISUSED WATERWHEEL 20 And an extract of family history DATES FOR YOUR DIARY: Tinworking, Mining and Miners in Mary Tavy A Community Day Saturday 27th April 2019 Coronation Hall, Mary Tavy 10:00 am—5:00 pm Open to all, this day will explore the rich legacy of copper, lead and tin mining in the Mary Tavy parish area. Two talks, a walk, exhibitions, bookstalls and afternoon tea will provide excellent stimulation for discovery and discussion. The event will be free of charge but donations will be requested for morning tea and coffee, and afternoon cream tea will be available at £4.50 per head. Please indicate your attendance by emailing [email protected] – this will be most helpful for catering arrangements. Programme 10:00 Exhibitions, bookstalls etc. -

The Wonders of Low Season!

July 2020 If you have any questions or would like more information, please do not hesitate to get in touch. We are open all year round. Tel: 01264 335527 [email protected] www.cornishholiday.info [email protected] Moody Skies over a rugged Cornish Coastline The wonders of Low Season! Cornwall is not just about those lazy, sunny days on the beach. It has so much more to offer especially in Low Season, the Shoulder Months, Non-School Holidays, Autumn and Winter or however you prefer to refer to it. Our properties in fantastic locations around Cornwall offer the ideal opportunity to get away from it all. Have some peace and quiet enabling you to relax and unwind while being warm and cosy at a fraction of the cost you would pay in the summer months. Open everyday of the year you can simply pick your preferred dates, book online direct with us and look forward to a wonderful stay. Many attractions are open during this time and the sea can actually retain a lot of its warmth from the summer months so if you do fancy a swim it’s a great time to visit. We hope to welcome you in the relaxing, quiet months. Alec & Helen Wind Turbines against Dark Clouds near Newquay. Please remember any companies or contact details given do not mean they are in anyway indorsed by Cornish Holiday. They are purely contacts for your information. Any activities are undertaken entirely at your own risk. July 2020 If you have any questions or would like more information, please do not hesitate to get in touch. -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

1859 Cornwall Quarter Sessions & Assizes

1859 Cornwall Quarter Sessions & Assizes Table of Contents 1. Epiphany Sessions ...................................................................................................................... 1 2. Lent Assizes .............................................................................................................................. 24 3. Easter Sessions ........................................................................................................................ 42 4. Midsummer Sessions 1859 ...................................................................................................... 51 5. Summer Assizes ....................................................................................................................... 76 6. Michaelmas Sessions ............................................................................................................. 116 ========== Royal Cornwall Gazette, Friday January 7, 1859 1. Epiphany Sessions These sessions opened at the County Hall, Bodmin, on Tuesday the 4th inst., before the following Magistrates:— Sir Colman Rashleigh, Bart., John Jope Rogers, Esq., Chairmen. C. B. Graves Sawle, Esq., Lord Vivian. Thomas Hext, Esq. Hon. G.M. Fortescue. F.M. Williams, Esq. N. Kendall, Esq., M.P. H. Thomson, Esq. T. J. Agar Robartes, Esq., M.P. J. P. Magor, Esq. R. Davey, Esq., M.P. R. G. Bennet, Esq. J. St. Aubyn, Esq., M.P. Thomas Paynter, Esq. J. King Lethbridge, Esq. R. G. Lakes, Esq. W. H. Pole Carew, Esq. J. T. H. Peter, Esq. J. Tremayne, Esq. C. A. Reynolds, Esq. F. Rodd, -

Environmentol Protection Report WATER QUALITY MONITORING

5k Environmentol Protection Report WATER QUALITY MONITORING LOCATIONS 1992 April 1992 FW P/9 2/ 0 0 1 Author: B Steele Technicol Assistant, Freshwater NRA National Rivers Authority CVM Davies South West Region Environmental Protection Manager HATER QUALITY MONITORING LOCATIONS 1992 _ . - - TECHNICAL REPORT NO: FWP/92/001 The maps in this report indicate the monitoring locations for the 1992 Regional Water Quality Monitoring Programme which is described separately. The presentation of all monitoring features into these catchment maps will assist in developing an integrated approach to catchment management and operation. The water quality monitoring maps and index were originally incorporated into the Catchment Action Plans. They provide a visual presentation of monitored sites within a catchment and enable water quality data to be accessed easily by all departments and external organisations. The maps bring together information from different sections within Water Quality. The routine river monitoring and tidal water monitoring points, the licensed waste disposal sites and the monitored effluent discharges (pic, non-plc, fish farms, COPA Variation Order [non-plc and pic]) are plotted. The type of discharge is identified such as sewage effluent, dairy factory, etc. Additionally, river impact and control sites are indicated for significant effluent discharges. If the watercourse is not sampled then the location symbol is qualified by (*). Additional details give the type of monitoring undertaken at sites (ie chemical, biological and algological) and whether they are analysed for more specialised substances as required by: a. EC Dangerous Substances Directive b. EC Freshwater Fish Water Quality Directive c. DOE Harmonised Monitoring Scheme d. DOE Red List Reduction Programme c. -

Notes on Mining Leats” British Mining No.37, NMRS, Pp.19-45

BRITISH MINING No.37 BRITISH MINING No.37 MEMOIRS 1988 Bird, R.H. 1988 “Notes on Mining Leats” British Mining No.37, NMRS, pp.19-45 Published by the THE NORTHERN MINE RESEARCH SOCIETY SHEFFIELD U.K. © N.M.R.S. & The Author(s) 1988. ISSN 0309-2199 NOTES ON MINING LEATS R.H. Bird “.... the means of putting to work many mines that would otherwise remain unworked, or if worked, could not be worked with profitable results.” Absalom Francis. 1874. SYNOPSIS Watercourses supplying mining works have been in use for centuries but their complexity increased during the 19th century, particularly in mining districts which were remote from coal supplies used for steam engines but which had sufficient river systems (or streams) of a dependable nature. Their role in Britain’s mining areas is discussed, with examples from overseas locations. An attempt is made to outline their construction methods and costs. In an age when water power reigned supreme and, indeed, for some time thereafter, mills and manufacturing industries were dependant on a steady supply of water to drive that prime mover, the water wheel. Flour mills, fulling mills and the early ferrous metal industries were sited next to reliable river or stream courses and could thus utilise this water source with little difficulty. Sometimes, the configuration of the stream was inconveniently placed for the mill site and the miller was forced to construct a ditch, from a dam upstream of his mill, and by this, lead the water to his wheel. After driving the wheel, the water was returned to the stream directly or through another ditch, the tailrace. -

Responsibilities for Flood Risk Management

Appendix A - Responsibilities for Flood Risk Management The Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) has overall responsibility for flood risk management in England. Their aim is to reduce flood risk by: • discouraging inappropriate development in areas at risk of flooding. • encouraging adequate and cost effective flood warning systems. • encouraging adequate technically, environmentally and economically sound and sustainable flood defence measures. The Government’s Foresight Programme has recently produced a report called Future Flooding, which warns that the risk of flooding will increase between 2 and 20 times over the next 75 years. The report produced by the Office of Science and Technology has a long-term vision for the future (2030 – 2100), helping to make sure that effective strategies are developed now. Sir David King, the Chief Scientific Advisor to the Government concluded: “continuing with existing policies is not an option – in virtually every scenario considered (for climate change), the risks grow to unacceptable levels. Secondly, the risk needs to be tackled across a broad front. However, this is unlikely to be sufficient in itself. Hard choices need to be taken – we must either invest in more sustainable approaches to flood and coastal management or learn to live with increasing flooding”. In response to this, Defra is leading the development of a new strategy for flood and coastal erosion for the next 20 years. This programme, called “Making Space for Water” will help define and set the agenda for the Government’s future strategic approach to flood risk. Within this strategy there will be an overall approach to the assessing options through a strong and continuing commitment to CFMPs and SMPs within a broader planning framework which will include River Basin Management Plans prepared under the Water Framework Directive and Integrated Coastal Zone Management. -

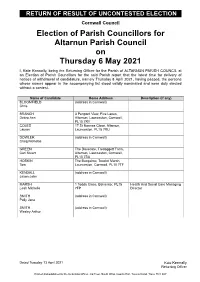

Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BLOOMFIELD (address in Cornwall) Chris BRANCH 3 Penpont View, Five Lanes, Debra Ann Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7RY COLES 17 St Nonnas Close, Altarnun, Lauren Launceston, PL15 7RU DOWLER (address in Cornwall) Craig Nicholas GREEN The Dovecote, Tredoggett Farm, Carl Stuart Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7SA HOSKIN The Bungalow, Trewint Marsh, Tom Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7TF KENDALL (address in Cornwall) Jason John MARSH 1 Todda Close, Bolventor, PL15 Health And Social Care Managing Leah Michelle 7FP Director SMITH (address in Cornwall) Polly Jane SMITH (address in Cornwall) Wesley Arthur Dated Tuesday 13 April 2021 Kate Kennally Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, 3rd Floor, South Wing, County Hall, Treyew Road, Truro, TR1 3AY RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Antony Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ANTONY PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. -

SOUTH WESTERN ELECTRICITY BOARD AREA Regional and Local Electricity Systems in Britain

ABSTRACT Public electricity supplies began in Britain during the 1880s. By 1900 most urban places with over 50,000 population had some form of service, at least in the town centre. Gerald T Bloomfield Professor Emeritus, University of Guelph THE SOUTH WESTERN ELECTRICITY BOARD AREA Regional and Local Electricity Systems in Britain 1 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 The South Western Electricity Board Area ................................................................................................... 2 Constituents of the South Western Electricity Board Area .......................................................................... 3 Development of Electricity Supply Areas ...................................................................................................... 5 I Local Initiatives.................................................................................................................................. 7 II State Intervention ........................................................................................................................... 12 III Nationalisation ................................................................................................................................ 24 Electricity Distribution ........................................................................................................................ 24 Electricity Generation and Transmission -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF SOCIAL AND HUMAN SCIENCES Geography and Environment Spatiotemporal population modelling to assess exposure to flood risk by Alan D. Smith Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF SOCIAL AND HUMAN SCIENCES Geography and Environment Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SPATIOTEMPORAL POPULATION MODELLING TO ASSESS EXPOSURE TO FLOOD RISK Alan Daniel Smith There is a growing need for high resolution spatiotemporal population estimates which allow accurate assessment of population exposure to natural hazards. Populations vary over range of time scales and cyclical patterns. This has important implications for how researchers and policy makers undertake hazard risk assessments. Traditionally, static population counts aggregated to arbitrary areal units have been used. -

Stroll Back the Years 2019.Xlsx

BODMIN STROLL BACK THE YEARS WALK PROGRAMME JANUARY to JUNE 2019 MONTH DATE ROUTE LEVEL PARKING INFORMATION January 7th Respryn to Bodmin Parkway 1 £1 parking, free for NT members at Respryn car park. PL30 4AH Grid Ref: 099636 2019 14th Athelstan Circular Walk 2 Fees apply for parking in Priory car park. PL31 2DQ Grid Ref: 073668 21st Lostwithiel Walk * please note 9.30 start 3 Free parking Lostwithiel Community Centre . PL22 0HE Grid Ref: 105598 28th Respryn to Lanhydrock House 3 £1 parking, free for NT members at Respryn car park. PL30 4AH Grid Ref: 099636 February 4th Helland Bridge 1 Free parking Camel Trail. PL30 4QR Grid Ref: 064714 11th Borough Arms to Camel Vineyard 1 Free parking by the Borough Arms Pub. PL31 2RD Grid Ref: 047675 18th St Gurons Way 2 Free parking Lower car park, Dragons Leisure Centre. PL31 1DE Grid Ref: 077653 25th Wheal Martyn China Clay (New walk) 1 Parking at China Clay Country Park, Wheal Martyn PL26 8XG Grid Ref:SX 005554 March 4th Dunmere & The Jail Walk 3 Free parking at Scarlets Well near Bodmin Jail. PL31 2RS Grid Ref: 062674 11th Ponts Mill / Luxulyan 3 Free parking in Ponts Mill (off A390 on the right before St Blazey) PL24 2RR Grid Ref: 073562 18th Par Sands Beach and Canal (New walk) 1 Car parking near Milo's Restaurant , opposite lake. PL24 2AS Grid Ref: 086533 25th Bishops Wood 10.15 start 3 Free parking at Bishops Wood. Better approached via Nanstallan.PL30 3AN Grid Ref: 013694 April 1st Respryn to Restormel Castle 3 £1 parking, free for NT members at Respryn car park. -

228 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

228 bus time schedule & line map 228 Callington View In Website Mode The 228 bus line (Callington) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Callington: 3:50 PM (2) Gloweth: 7:03 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 228 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 228 bus arriving. Direction: Callington 228 bus Time Schedule 60 stops Callington Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Truro College, Gloweth Tuesday Not Operational National Tyres, Truro Benallack Court, Truro Wednesday Not Operational Tregolls Road Dual Carriageway, Truro Thursday Not Operational Tremorvah Barton, Truro Friday 3:50 PM Tregolls Road Hill, Truro Saturday Not Operational Waitrose, Truro Newquay Road, Truro River View, Tresillian 228 bus Info Direction: Callington Carrs Garage, Tresillian Stops: 60 Trip Duration: 110 min Fal Garage, Tresillian Line Summary: Truro College, Gloweth, National Tyres, Truro, Tregolls Road Dual Carriageway, Truro, Fairfax Road, Tresillian Tregolls Road Hill, Truro, Waitrose, Truro, River View, Tresillian, Carrs Garage, Tresillian, Fal Garage, Mercedes Garage, Tresillian Tresillian, Fairfax Road, Tresillian, Mercedes Garage, Tresillian, Trewithen Gardens, Probus, New Stables, Grampound Road, Old Hill, Grampound, Dolphin Inn, Trewithen Gardens, Probus Grampound, Penans, Hewas Water, St Mewan School, St Mewan, Penwinnick Road, St Austell, New Stables, Grampound Road Polmear Road, Mount Charles, Car Wash, Mount Charles, Holmbush Road, Holmbush, Holmbush Inn,