The Relationship of Various Audience Composition Factors to Television Program Types

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THE TELEVISED SOUTH: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DOMINANT READINGS OF SELECT PRIME-TIME PROGRAMS FROM THE REGION By COLIN PATRICK KEARNEY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2020 © 2020 Colin P. Kearney To my family ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A Doctor of Philosophy signals another rite of passage in a career of educational learning. With that thought in mind, I must first thank the individuals who made this rite possible. Over the past 23 years, I have been most fortunate to be a student of the following teachers: Lori Hocker, Linda Franke, Dandridge Penick, Vickie Hickman, Amy Henson, Karen Hull, Sonya Cauley, Eileen Head, Anice Machado, Teresa Torrence, Rosemary Powell, Becky Hill, Nellie Reynolds, Mike Gibson, Jane Mortenson, Nancy Badertscher, Susan Harvey, Julie Lipscomb, Linda Wood, Kim Pollock, Elizabeth Hellmuth, Vicki Black, Jeff Melton, Daniel DeVier, Rusty Ford, Bryan Tolley, Jennifer Hall, Casey Wineman, Elaine Shanks, Paulette Morant, Cat Tobin, Brian Freeland, Cindy Jones, Lee McLaughlin, Phyllis Parker, Sue Seaman, Amanda Evans, David Smith, Greer Stene, Davina Copsy, Brian Baker, Laura Shull, Elizabeth Ramsey, Joann Blouin, Linda Fort, Judah Brownstein, Beth Lollis, Dennis Moore, Nathan Unroe, Bob Csongei, Troy Bogino, Christine Haynes, Rebecca Scales, Robert Sims, Ian Ward, Emily Watson-Adams, Marek Sojka, Paula Nadler, Marlene Cohen, Sheryl Friedley, James Gardner, Peter Becker, Rebecca Ericsson, -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Spring 2014 Commencement Program

TE TA UN S E ST TH AT I F E V A O O E L F A DITAT DEUS N A E R R S I O Z T S O A N Z E I A R I T G R Y A 1912 1885 ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT AND CONVOCATION PROGRAM Spring 2014 May 12 - 16, 2014 THE NATIONAL ANTHEM THE STAR SPANGLED BANNER O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light, What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming? Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight O’er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming? And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there. O say does that Star-Spangled Banner yet wave O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave? ALMA MATER ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Where the bold saguaros Raise their arms on high, Praying strength for brave tomorrows From the western sky; Where eternal mountains Kneel at sunset’s gate, Here we hail thee, Alma Mater, Arizona State. —Hopkins-Dresskell MAROON AND GOLD Fight, Devils down the field Fight with your might and don’t ever yield Long may our colors outshine all others Echo from the buttes, Give em’ hell Devils! Cheer, cheer for A-S-U! Fight for the old Maroon For it’s Hail! Hail! The gang’s all here And it’s onward to victory! Students whose names appear in this program have completed degree requirements. -

Ed Roche Audiovisual Collection Finding Aid (PDF)

Title of Collection: Ed Roche Audio Collection Reference Code: US-MoKcUMS-MSAM0005 Repository: Marr Sound Archives UMKC Miller Nichols Library 800 E. 51st Street Kansas City, MO 64110 Creator: Roche, Ed Biographical History: From 1935 until his retirement in 1991, Ed Roche recorded the sounds of Kansas City. The first engineer for Kansas City’s Municipal Auditorium, Roche installed and operated the then state of-the-art audio system. He meticulously documented music and civic events, including performances of the Kansas City Philharmonic. In 1952, Roche established Crown Recording Studio. Crown quickly became one of Kansas City’s leading studios. Over the years, Roche recorded thousands of bands, choruses and radio programs including the Kansas City Hour. Roche produced tapes for the Nazarene Church that were distributed internationally. During the 1980s, he preserved the open-reel tapes and instantaneous cut discs for the Harry Truman Presidential Library. Date Range: 1935-1967 Extent: 7 linear feet, includes 629 grooved discs and 15 open reel tapes. Scope and Content: The Ed Roche Audio Collection contains many unique items recorded in the Kansas City area, including political speeches, musical performances, religious services, and advertisements for businesses and organizations. The Kansas City Philharmonic Orchestra and the Kansas City Conservatory of Music are strongly represented with numerous recordings of each entity. Finally, the collection also holds some national radio programs, such as “The Guiding Light,” “Hymns of All Churches,” and “Michael Shayne.” University of Missouri – Kansas City Marr Sound Archives Conditions of Access: The collection is open for research and educational use. The physical items in this collection are non- circulating. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

1 Sex Differences in Preferences for Humor Produced by Men Or Women: Is Humor in the Sex of the Perceiver? [Word Count = <25

1 Sex differences in preferences for humor produced by men or women: Is humor in the sex of the perceiver? [word count = <2500] Address correspondence to: 2 ABSTRACT It is a common argument that men are funnier than women. Recently, this belief has received modest empirical support among evolutionary psychologists who argue that humor results from sexual selection. Humor signals intelligence, and women thus use humor to discriminate between potential mates. From this, it follows that in addition to men being skilled producers of humor, women should be skilled perceivers of humor. Extant research has focused on humor production; here we focus on humor perception. In three studies, men and women identified the most humorous professional comedian (Studies 1 and 2) or individual they know personally (Study 3). We found large sex differences. In all three studies, men overwhelmingly preferred humor produced by other men, whereas women showed smaller (study 1) or no (studies 2 and 3) sex preference. We discuss biological and cultural roots of humor in light of these findings. 3 Sex differences in humor perception: Is humor in the sex of the perceiver? Although sex differences in the ability to produce humor have been debated at least since the 17th century (Congreve, 1695/1761; for more recent discussion, see the dialog between Hitchens and Stanley, Hitchens, 2007; Stanley, 2007), surprisingly few empirical studies exist on the topic. Yet understanding any sex difference in humor production or perception is important, since research suggests that humor mediates crucial social, psychological, and physiological processes. Socially, humor performs invaluable roles in persuasion (Mulkay, 1988) and managing personal relationships (Shiota, Campos, Keltner, & Hertenstein, 2004). -

Televising the South: Race, Gender, and Region in Primetime, 1955-1980

TELEVISING THE SOUTH: RACE, GENDER, AND REGION IN PRIMETIME, 1955-1980 by PHOEBE M. BRONSTEIN A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2013 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Phoebe M. Bronstein Title: Televising the South: Race, Gender, and Region in Primetime, 1955-1980 This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of English by: Carol Stabile Chairperson Priscilla Ovalle Core Member Courtney Thorsson Core Member Meslissa Stuckey Institutional Representative and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2013 ii © 2013 Phoebe M. Bronstein This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Phoebe Bronstein Doctor of Philosophy Department of English September 2013 Title: Televising the South: Race, Gender, and Region in Primetime, 1955-1980 This dissertation traces the emergence of the U.S. South and the region’s role in primetime television, from the post-World War II era through Reagan’s election in 1980. These early years defined, as Herman Gray suggests in Watching Race, all subsequent representations of blackness on television. This defining moment, I argue, is one inextricably tethered to the South and the region’s anxiety ridden and complicated relationship with television. This anxiety was rooted in the progress and increasing visibility of the Civil Rights Movement, concern over growing white southern audiences in the wake of the FCC freeze (ended in 1952), and the fear and threat of a southern backlash against racially progressive programming. -

The BG News November 8, 1979

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 11-8-1979 The BG News November 8, 1979 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News November 8, 1979" (1979). BG News (Student Newspaper). 3669. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/3669 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. The BT3 He ws Bowling "Green 'Stale University thurs- Grants to aid women, minority grads day n-8-79 by Paul O'Donnell "We are trying to increase the pool of Staff reporter University among top-funded institutions qualified minority students," he said. The proposal for next year has Freshman loses The University has received $140,400 STONE SAID the federal funds will plementation of an effective graduate standing of each individual graduate already been submitted, and Stone said in grants from the Department of allow for 18 fellowships this year: two program. student, he noted. The areas of study he has requested added support. bid for mayor Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) in mathematics, seven in biological are identified by the University in the He said he hopes to obtain three more to assist minority and women students sciences, five in graduate business ad- HE WAS required to develop a writ- proposal submitted to HEW. -

THE PRESS Friday, December 13, 1963 TELEVISION LOG for the WEEK FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY

A-8—THE PRESS Friday, December 13, 1963 TELEVISION LOG FOR THE WEEK FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY. MONDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY DECEMBER 16 DECEMBER 13 DECEMBER 14 DECEMBER 15 DECEMBER 18 DECEMBER 19 12:00 ( 2) Burns and Alien 11:00 ( 7) AFL Game 12:00 ( 2) Burns and Alien ( 4) People Will Talk 11:00 ( 2) NFL Game ( 4) People Will Talk 12:00 ( 2) Burns and Alien 12:00 ( 2) Burns and Alien ( 5) Dateline Europe 12:00 ( 2) Sky KKing 12:00 ( 2) Insight ( 5) Cross Current ( 4) People Will Talk ( 4) People Will Talk ( 7) Tennessee ^rme ( 4) Exploring ( 4) Jr. Rose bowl ( 7) Tennessee Ernie ( 5) Overseas Adventure ( 5) Overseas Adventure ( 9) Hour of St. Francis ( 9) Searchlight on ( "<) Ernie Ford (11) Sheriff John (13) Cartoons ( 7) Press Conference Delinquency ( 7) Tennessee Ernie 9) Books and Ideaa (13) Oral Roberts ( 9) Dr. Spock 12:30 ( 2) As World Turns 12:30 ( 2) Do You Know (11) Sheriff John (11) Sheriff John ( 5) TV Bingo (13) Movie (11) Sheriff John (13) Movie ( 7) Father Knows Best ( 5) Movie 12:30 ( 5) Movie ( 9) Mr. D.A. "Tonight We Raid Calali" 12:30 ( 2) As World Turn* (13) Movie 12:30 ( 2) As World Turns 1:00 (2) News Lee J. Cohb (4 ) The Doctors ( 4) The Doctors 12:45 ( 5) Dateline Europe ( 7) Discovery 12:30 ( 2) As World Turns 1:00 ( 2) Password ( 4) Ornamental World ( 5) TV Bingo ( 5) TV Bingo (13) Social Security ( 7) Father Knows Best (4 ) The Doctors ( 7) Father Knows Best ( 4) Loretta Young ( 5) Movie ( 5) TV Bingo ( 5) Douglas Fairbanks ( 9) Mr. -

Skelton United Nations Concert, February 27, 1968

CBS Television Network Press Information, 51 West 52 Street, New York, N.Y.10019 February 21, 1968 VICE PRESIDENT HUMPHREY TO INTRODUCE RED SKELTON'S SPECIAL PROGRAM FEB. 27 "Laughter - The Universal Language, 11 Skelton 1 s Pantomime Concert, Performed Before International U.N. Diplomatic Audience in New York Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey introduces Red Skelton and welcomes his distinguished audience of United Nations diplomats to 11 Laughter- The Universal Language," Skelton's pantomime concert to be broadcast on "The Red Skelton Hour 11 Tuesday, Feb. 27 (8:30-9:30 PM, EST) in color on the CBS Television Network. The Vice President taped his introductory remarks in Washington on Wednesday, Feb. 21 as a preface for the pantomime concert. The con cert itself was taped the previous night in New York before a black-tie audience representing 73 missions at the United Nations. Mr. Humphrey was unable to attend the New York performance because of Washington commitments. 11 Laughter - The Universal Language 11 is performed by Skelton without dialogue, except for the announcer 1 s spoken introductions, which are in English and French. Following the taping of the broadcast, Skelton and Mrs . Skelton greeted the diplomatic audience at a formal reception tendered by the (More) '. CBS Television Network 2 CBS Television Network and the United Nation: Association -U.S.A. at the Plaza Hotel in New York. In the receiving line with the Skeltons were Thomas H. Dawson, President of the CBS Television Network, and Mrs. Dawson; Oscar A. deLima, Chairman of the Executive Committee of the United Nations Asso ciation, and Mrs. -

The Webfooter

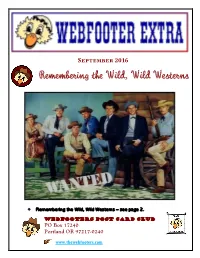

September 2016 Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns – see page 2. Webfooters Post Card Club PO Box 17240 Portland OR 97217-0240 www.thewebfooters.com Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Before Batman, before Star Trek and space travel to the moon, Westerns ruled prime time television. Warner Brothers stable of Western stars included (l to r) Will Hutchins – Sugarfoot, Peter Brown – Deputy Johnny McKay in Lawman, Jack Kelly – Bart Maverick, Ty Hardin – Bronco, James Garner – Bret Maverick, Wade Preston – Colt .45, and John Russell – Marshal Dan Troupe in Lawman, circa 1958. Westerns became popular in the early years of television, in the era before television signals were broadcast in color. During the years from 1959 to 1961, thirty-two different Westerns aired in prime time. The television stars that we saw every night were larger than life. In addition to the many western movie stars, many of our heroes and role models were the western television actors like John Russell and Peter Brown of Lawman, Clint Walker on Cheyenne, James Garner on Maverick, James Drury as the Virginian, Chuck Connors as the Rifleman and Steve McQueen of Wanted: Dead or Alive, and the list goes on. Western movies that became popular in the 1940s recalled life in the West in the latter half of the 19th century. They added generous doses of humor and musical fun. As western dramas on radio and television developed, some of them incorporated a combination of cowboy and hillbilly shtick in many western movies and later in TV shows like Gunsmoke. -

Pictorial. Magazine

EK'S COMPLETE TELEVISION PROGRAMS THE SUNDAY NORTH JERSEY'S ONLY WEEKLY PICTORIAL. MAGAZINE ews Highlights of Clifton East Paters4n Fair Lawn Garfield Haledon Hawthorne Lodi Little Falls Mountain View h Haledon Paterson Passaic Pompton Lakes rospect Park Sidgac To owa oyne West Paterson DOWNTOWN CAMPUS MARCH 27, 1960 VOL. XXXII, No. 13 435 STRAIGHT STREET PATERSON, N.J. MUlberry 4-7880 GiftDep•rtment Living Rooms Bedrooms- Bedding Dining Rooms Furni.'•• Accessories Carpeting Appliances THE IDEAL PLACE TO DINE AND WINE -- l•/.t,,..•. ITALIAN.AMERICAkKITCHEN q,•n-.-*. :.,,,• 'i• t SEA OOD :*• q ß BROILED LOBSTER --, -- DAILY FROGS' I,EG$ - SY)FT SHELL CRAL•:• - BLUEFISH - RAINBO%% 21/2-HOUR OPERA COLORCAST-- Cesare Siepi (left) as Don TROUT - ]-iALIBUI' - SALMON - SHRIMPS- SCALLOPB- Giovanni -- title character in the Mozart work to be presented in English by the NBC Opera Company Sunday, April 10- threat- 168 BELMONTAVE. {Cor. Burhans).HALEDON - - - LAmbert 5-911S ens his servant Leporello (James Pease, kneeling) as Donna OYSTERS- CLAM- COD FISH - SP•ORD FISH- DAILY Elyira (Helen George) intervenes. Masetto (John Reardon) and his fiancee Zerlina (Judith Raskin) look on. Also in the cast of the NBC-TV Network presentation are Leontyne Price, Charles K..L. Davis and John McCurdy. I. PARRILLO TheMan from Equitable asks- YouwaKt your child to havea better placein the sun, don't you? OF'COURSE YOU DO. But like someparents you f•g- ure,"there's still plenty of time."Then, bdore you knowit, they'reall grown up and need your help •o givethem that important start toward a pro•ion, careeror business,or in settingup a home.Make surenow that your "helpinghand" will be there whenit isneeded.