IIJ*EW Counties in England Have Altered So

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tavistock Abbey

TAVISTOCK ABBEY Tavistock Abbey, also known as the Abbey of Saint Mary and Saint Rumon was originally constructed of timber in 974AD but 16 years later the Vikings looted the abbey then burned it to the ground, the later abbey which is depicted here, was then re-built in stone. On the left is a 19th century engraving of the Court Gate as seen at the top of the sketch above and which of course can still be seen today near Tavistock’s museum. In those early days Tavistock would have been just a small hamlet so the abbey situated beside the River Tavy is sure to have dominated the landscape with a few scattered farmsteads and open grassland all around, West Down, Whitchurch Down and even Roborough Down would have had no roads, railways or canals dividing the land, just rough packhorse routes. There would however have been rivers meandering through the countryside of West Devon such as the Tavy and the Walkham but the land belonging to Tavistock’s abbots stretched as far as the River Tamar; packhorse routes would then have carried the black-robed monks across the border into Cornwall. So for centuries, religious life went on in the abbey until the 16th century when Henry VIII decided he wanted a divorce which was against the teachings of the Catholic Church. We all know what happened next of course, the Dissolution of the Monasteries, when along with all the other abbeys throughout the land, Tavistock Abbey was raised to the ground. Just a few ruined bits still remain into the 21st century. -

NEWSLETTER September 2019

President: Secretary: Treasurer: David Illingworth Nigel Webb Malcolm Thorning 01305 848685 01929 553375 01202 659053 NEWSLETTER September 2019 FROM THE HON. SECRETARY Since the last Newsletter we have held some memorable meetings of which the visit, although it was a long and tiring day, to Buckfast Abbey must rank among the best we have had. Our visit took place on Thursday 16th May 2019 when some sixteen members assembled in the afternoon sunshine outside the Abbey to receive a very warm welcome from David Davies, the Abbey Organist. He gave us an introduction to the acquisition and building of the organ before we entered the Abbey. The new organ in the Abbey was built by the Italian firm of Ruffatti in 2017 and opened in April 2018. It has an elaborate specification of some 81 stops spread over 4 manuals and pedals. It is, in effect, two organs with a large west-end division and a second extensive division in the Choir. There is a full account of this organ in the Organist’s Review for March 2018 and on the Abbey website. After the demonstration we were invited to play. Our numbers were such that it was possible for everyone to take the opportunity. David was on hand to assist with registration on this complex instrument as the console resembled the flight deck of an airliner. Members had been asked to prepare their pieces before-hand and this worked well with David commenting on the excellent choice of pieces members had chosen to suit the organ. We are most grateful to David Davies for making us so welcome and help throughout the afternoon. -

9780521633482 INDEX.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 0521633486 - A History of the English Parish: The Culture of Religion from Augustine to Victoria N. J. G. Pounds Index More information INDEX abandonment, of settlement 90–1 rail 442 Abbots Ripton, briefs 270, 271 (map) tomb 497 abortion 316–17; herbs for 316 altarage 54 Abraham and Isaac 343 Altarnon church 347, 416 absenteeism 564 Alvingham priory 63 abuse, verbal 258 Ancaster stone 402 accounts, clerical 230 Andover parish 22, 23 (map) parochial 230 Anglican liturgy 481 wardens’ 230 Anglo-Saxon churches 113 acolyte 162 Annates 229 Act of Unification 264 anticlericalism 220, 276 Adderbury, building of chancel 398–9 in London 147 adultery 315 apparition 293 Advent 331 appropriation 50–4, 62–6, 202 (map) Advowson 42, 50, 202 apse 376, 378 Ælfric’s letter 183 Aquae bajulus 188 Æthelberht, King 14 Aquinas, Thomas 161, 459 Æthelflaeda of Mercia 135 archdeaconries 42 Æthelstan, law code of 29 archdeacons 162, 181, 249 affray, in church courts 291–2; over seats 477 courts of 174–6, 186, 294–6, 299, 303 aged, support of 196 and wills 307 agonistic principle 340 archery 261–2 aisles 385–7, 386 (diag.) Arles, Council of 7, 9 ales 273, see church-ales, Scot-ales Ascension 331 Alexander III, Pope 55, 188, 292 Ashburton 146 Alkerton chapel 94 accounts of 231 All Hallows, Barking 114 church-ale at 241 All Saints, Bristol, library at 286–8 pews in 292 patrons of 410 Ashwell, graffiti at 350–1 All Saints’ Day 331, 333 audit, of wardens’ accounts 182–3 altar 309 auditory church 480 candles on 434 augmentations, court of 64 consecration of 442–3 Augustinian order 33, 56 covering of 437 Austen, Jane 501 desecration of 454 Avicenna 317 frontals 430, 437 Aymer de Valence 57 material of 442 number of 442 Bag Enderby 416 placement of 442 Bakhtin, Mikhail 336 position of 486 balance sheet of parish 236–9 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521633486 - A History of the English Parish: The Culture of Religion from Augustine to Victoria N. -

The Network RSCM Events in Your Local Area June – October 2016

the network RSCM events in your local area June – October 2016 The Network June 2016.indd 1 16/05/2016 11:17:47 Welcome THE ROYAL SCHOOL OF You can travel the length and CHURCH MUSIC breadth of the British Isles this Registered Charity No. 312828 Company Registration No. summer, participate in and 00250031 learn about church music in 19 The Close, Salisbury SP1 2EB so many forms with the RSCM. T 01722 424848 I don’t think I’ve ever seen quite F 01722 424849 E [email protected] so varied and action-packed an W www.rscm.com edition of The Network. I am Front cover photograph: most grateful to the volunteers on the RSCM’s local Area RSCM Ireland award winners committees, and I hope you will feel able to take up this recording for an RTÉ broadcast, oering. November 2015 How to condense it? Awards, BBC broadcast, The Network editor: Contemporary worship music, Diocesan music day, Cathy Markall Evensongs, Food-based events, Gospel singing, Harvest Printed in Wales by Stephens & George Ltd anthems, Instrumental music, John Rutter, Knighton pilgrimage, Lift up your Voice, Music Sunday, National Please note that the deadline for submissions to the next courses, explore the Organ, converting Pianists, edition of The Network is celebrating the Queen’s birthday, Resources for small and 1 July 2016. rural churches, Singing breaks, Training organists, Using the voice well, Vespers, Workshops, events for Young ABOUT THE RSCM people. Excellence and zeal, I hope. The RSCM is a charity Don’t forget that there is also the triennial committed particularly to International Summer School in Liverpool in August promoting the study, practice and improvement of music at which you can experience many of these things in in Christian worship. -

Stage 1-Route-Guide-V3.Cdr

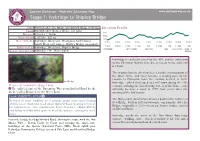

O MO R T W R A A Y D w w k u w . o .d c ar y. tmoorwa Start SX 6366 5627 Ivy Bridge on Harford Road, Ivybridge Elevation Profile Finish SX 6808 6289 Shipley Bridge car park 300m Distance 10 miles / 16 km 200m 2,037 ft / 621 m Total ascent 100m Refreshments Ivybridge, Bittaford, Wrangaton Golf Course, 0.0km 2.0km 4.0km 6.0km 8.0km 10.0km 12.0km 14.0km 16.0km South Brent (off route), Shipley Bridge (seasonal) 0.0mi 1.25mi 2.5mi 3.75mi 5mi 6.25mi 7.5mi 8.75mi 10mi Public toilets Ivybridge, Bittaford, Shipley Bridge IVYBRIDGE BITTAFORD CHESTON AISH BALL GATE SHIPLEY Tourist information Ivybridge (The Watermark) BRIDGE Ivybridge is easily accessed via the A38, and the only town on the Dartmoor Way to have direct access to the main rail network. The original hamlet developed at a handy crossing point of the River Erme, and later became a staging post on the London to Plymouth road; the railway arrived in 1848. Ivy Bridge Ivybridge - which developed as a mill town during the 19th Please refer also to the Stage 1 map. century, utilising the fast-flowing waters of the Erme - only S The official start of the Dartmoor Way is on Harford Road by the officially became a town in 1977, four years after the medieval Ivy Bridge over the River Erme. opening of the A38 bypass. POOR VISIBILITY OPTION a The Watermark (local information) is down in the town near In times of poor visibility or if anxious about your route-finding New Bridge, built in 1823 just downstream from the older Ivy abilities over moorland head down Harford Road, bearing left near Bridge, originally a 13th-century packhorse bridge, passed the bottom to meet the roundabout. -

Advent 2015 Two Recent Publications: a Book and a Film

Advent 2015 Two Recent Publications: A Book and a Film Monks have long been known for their diverse tal- on the afternoon of Sunday, September 13, attended ents and interests: teachers, farmers, writers, artists. by a number of Fr Stephen’s former students and Among the last-named was Fr Stephen Reid of our other friends of the abbey. It is available in our gift community, who at the time of his death in 1989 had shop for $20, and can be ordered by mail for an produced a remarkable number of sculptures and additional four dollars to cover shipping costs. paintings. In the past few years, an art critic named We think our readers would also like to know Bruce Nixon has been working on a publication that of a documentary about Benedictine life that has offers a thoughtful, carefully researched interpretive been produced for the Catholic French television text that considers Fr Stephen’s art in the context channel KTO, founded in 1999 by the late cardinal- of his life as a monk. Titled A Communion of Saints, archbishop of Paris, Jean-Marie Lustiger. Titled Le this forty-page illus- Temps et la règle bénédictine, this 52-minute film was trated catalog includes first telecast in December, 2014. The director, Patrice photographs made in Cros, has twice visited St Anselm’s and hopes accordance with the to produce English-language documentaries on archival standards of this and similar Benedictine topics, such as work, museum documenta- community, authority, and poverty. If any of our tion and so serves to readers have suggestions of sponsors who could preserve the legacy finance such a project, please let Abbot James know. -

Microsoft Schools

Microsoft Schools Region Country State Company APAC Vietnam THCS THẠCH XÁ APAC Korea GoYang Global High School APAC Indonesia SMPN 12 Yogyakarta APAC Indonesia Sekolah Pelita Harapan Intertiol APAC Bangladesh Bangladesh St. Joseph School APAC Malaysia SMK. LAJAU APAC Bangladesh Dhaka National Anti-Bullying Network APAC Bangladesh Basail government primary school APAC Bangladesh Mogaltula High School APAC Nepal Bagmati BernHardt MTI School APAC Bangladesh Bangladesh Letu mondol high school APAC Bangladesh Dhaka Residential Model College APAC Thailand Sarakhampittayakhom School English Program APAC Bangladesh N/A Gabtali Govt. Girls' High School, Bogra APAC Philippines Compostela Valley Atty. Orlando S. Rimando National High School APAC Bangladesh MOHONPUR GOVT COLLEGE, MOHONPUR, RAJSHAHI APAC Indonesia SMAN 4 Muaro Jambi APAC Indonesia MA NURUL UMMAH LAMBELU APAC Bangladesh Uttar Kulaura High School APAC Malaysia Melaka SMK Ade Putra APAC Indonesia Jawa Barat Sukabumi Study Center APAC Indonesia Sekolah Insan Cendekia Madani APAC Malaysia SEKOLAH KEBANGSAAN TAMAN BUKIT INDAH APAC Bangladesh Lakhaidanga Secondary School APAC Philippines RIZAL STI Education Services Group, Inc. APAC Korea Gyeonggi-do Gwacheon High School APAC Philippines Asia Pacific College APAC Philippines Rizal Institute of Computer Studies APAC Philippines N/A Washington International School APAC Philippines La Consolacion University Philippines APAC Korea 포항제철지곡초등학교 APAC Thailand uthaiwitthayakhom school APAC Philippines Philippines Isabel National Comprehensive School APAC Philippines Metro Manila Pugad Lawin High School APAC Sri Lanka Western Province Wise International School - Sri Lanka APAC Bangladesh Faridpur Govt. Girls' High School, Faridpur 7800 APAC New Zealand N/A Cornerstone Christian School Microsoft Schools APAC Philippines St. Mary's College, Quezon City APAC Indonesia N/A SMA N 1 Blora APAC Vietnam Vinschool Thành phố Hồ Chí APAC Vietnam Minh THCS - THPT HOA SEN APAC Korea . -

Our Ancient Parishes

O UR A IS NCIENT PAR HES , O R A L E C T U R E Q UATFO RD , MO RVILLE ASTO N EY RE 800 Y EARS AGO . D ELIVERED BEFO RE m BRIDGNORTH SO CIETY FO R THE PROMOTION OF RELIGIOUS AND USEFUL KNOWLEDGE WI H S ME DDI I N L INF RM I N , T O A T O A O AT O , ar m RE V. G EO RG E LEIG H WAs g M .A INCUMBENT E , , D O H MESTIC CHAPLAIN TO T E RIGHT HO N. LORD BRIDPO RT WW W ” JO UR AL O FF CE H GH STR E . CLEMENT ED KINS, PRINTER, N I , I E T 10 0 0013" T O T HE P A R I S H I O N E R S A N D L A N D O WN E R s O F U F RD M RVI L L E A N D S N E Y R E Q A T O , O A T O , THE F LL ING P GES ARE FFEC I N ELY DEDI ED O OW A A T O AT CAT , B Y HE I R F I H F UL S E RVA N T A T T , G E O RG E LE I G H WAS E Y . ERRATA. i r . 16 , for Anna n , ead Anna in i on s . 23, for cur ous e, read curious tone ' c hi f t r. 40, for chiefi reator, road c ef ores e ’ ’ 46 H nr th V TI . -

The Prom Groups

29 June 2018 Attendance Winning Forms ,Now we’ve said goodbye to our Year 11s, this week Penwortham Priory Post we can only provide attendance figures for the ‘Rest’ of the school. Rest - R5 (99.09%) Well done to Miss Creer’s form! Prospectus Photography Reply Slip Reminder Please could parents sign and return the photography consent form. At the end of term we will have a photographer in school to take images for the prospectus. We will be capturing day to day life in the school in a variety of different ways, across all activities and year Class of 2018 - The Prom groups. In order to do this The Year 11’s big night finally arrived on Wednesday when the pupils gathered one effectively, we really need last time to celebrate their years at Penwortham Priory Academy in style. as many of our pupils to be involved as possible. The event, held at Charnock Farm, Leyland, was the perfect opportunity for the hardworking Year 11s to let their hair down after the exam season and a chance Please sign and return the reply slip no later than to say goodbye to the staff who have challenged and supported them through their Friday, 6 July. school days. The pupils arrived in vehicles of many shapes and sizes, from stretched limousines ‘Get Caught Reading’ to a cavalcade of sports cars and even a camper van! Is Now Go! The pupils in the Prom Committee spent many hours organising the event alongside The English Department’s Assistant Headteacher, Mrs Crank. Attendees were reminded of their Year 7 school latest initiative is now live. -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

Medieval Cartularies of Great Britain: Amendments and Additions to the Dams Catalogue

MEDIEVAL CARTULARIES OF GREAT BRITAIN: AMENDMENTS AND ADDITIONS TO THE DAMS CATALOGUE Introduction Dr God+ Davis' Medieval Cartulari4s of Great Britain: a Short Catalogue (Longmans, 1958) has proved to be an invaluable resource for medieval historians. However, it is nearly forty years since its publication, and inevitably it is no longer completely up-to-date. Since 1958 a number of cartularies have been published, either as full editions or in calendar form. Others have been moved to different repositories. Some of those cartularies which Davis described as lost have fortunately since been rediscovered, and a very few new ones have come to light since the publication of the original catalogue. This short list seeks to remedy some of these problems, providing a list of these changes. The distinction drawn in Davis between ecclesiastical and secular cartularies has been preserved and where possible Davis' order has also been kept. Each cartulary's reference number in Davis, where this exists, is also given. Those other monastic books which Davis describes as too numerous to include have not been mentioned, unless they had already appeared in the original catalogue. Where no cartulary exists, collections of charters of a monastic house edited after 1958 have been included. There will, of course, be developments of which I am unaware, and I would be most grateful for any additional information which could be made known in a subsequent issue of this Bulletin. For a current project relating to Scottish cartularies see Monastic Research Bulletin 1 (1995), p. 11. Much of the information here has been gathered hmpublished and typescript library and repository catalogues. -

ABBEY FARM CARAVAN PARK, ORMSKIRK Lancashire

ABBEY FARM CARAVAN PARK, ORMSKIRK Lancashire Watching Brief Oxford Archaeology North February 2002 Mr Bridges Issue No.: 2001-02/120 OA(N) Job No.: L8193 NGR: SD 3099 4433 Document Title: ABBEY FARM CARAVAN PARK, ORMSKIRK, LANCASHIRE Document Type: Archaeological Watching Brief Client Name: Mr Bridges Issue Number: 2001-2002/120 OA Job Number: L8193 National Grid Reference: SD 3099 4433 Prepared by: Daniel Elsworth Position: Project Supervisor Date: February 2002 Checked by: Alison Plummer Signed……………………. Position: Project Manager Date: February 2002 Approved by: Rachel Newman Signed……………………. Position: Director Date: February 2002 Oxford Archaeology North © Oxford Archaeological Unit Ltd 2002 Storey Institute Janus House Meeting House Lane Osney Mead Lancaster Oxford LA1 1TF OX2 0EA t: (0044) 01524 848666 t: (0044) 01865 263800 f: (0044) 01524 848606 f: (0044) 01865 793496 w: www.oxfordarch.co.uk e: [email protected] Oxford Archaeological Unit Limited is a Registered Charity No: 285627 Disclaimer: This document has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be relied upon or used for any other project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Oxford Archaeology being obtained. Oxford Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than the purposes for which it was commissioned. Any person/party using or relying on the document for such other purposes agrees, and will by such use or reliance be taken to confirm their agreement to indemnify Oxford Archaeology for all loss or damage resulting therefrom.