The Option Contract: Irrevocable Not Irrejectable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Needs That Recital of Consideration?

DraftingDrafting aa newnew dayday Who needs that ‘recital of consideration’? By Kenneth A. Adams t’s hardly a shocking notion that are hereby acknowledged, the parties Farnsworth, Farnsworth on Contracts any given contract could contain hereto covenant and agree as follows. 150 (2d. ed. 1998).) It follows that Ione or more provisions that reflect Recitals of consideration raise a using instead the vague language of a an inaccurate or outdated view of con- number of issues of legal usage. For traditional recital of consideration tract law. What’s more noteworthy is example, NOW, THEREFORE is archa- would be equally ineffective. the fact one such provision — the tra- ic, while in consideration of the premises Similarly, a false recital of consider- ditional recital of consideration — is simply an obscure way of saying ation cannot create consideration appears in most corporate agreements. “therefore” and is superfluous given where there was none. If, in the con- In this article, I explain why that the preceding “therefore.” And refer- tract between Acme and Roe, Acme traditional recital of consideration ences to the value or sufficiency of recites falsely that the payment to Roe fails to serve its intended purpose and consideration are outdated: With the was in consideration of future services why omitting it could only improve a rise of the “bargain test of considera- and Acme subsequently refuses to pay contract. tion” reflected in the Restatement (Sec- the bonus, Acme should prevail in any The ostensible function of a recital ond) of Contracts, the focus of judges action brought by Roe if it succeeds in of consideration is to render enforce- has shifted from the substance of the proving that the recital was false. -

Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses | a National Survey | Shook, Hardy & Bacon

2020 — Force Majeure SHOOK SHB.COM and Common Law Defenses A National Survey APRIL 2020 — Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses A National Survey Contractual force majeure provisions allocate risk of nonperformance due to events beyond the parties’ control. The occurrence of a force majeure event is akin to an affirmative defense to one’s obligations. This survey identifies issues to consider in light of controlling state law. Then we summarize the relevant law of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. 2020 — Shook Force Majeure Amy Cho Thomas J. Partner Dammrich, II 312.704.7744 Partner Task Force [email protected] 312.704.7721 [email protected] Bill Martucci Lynn Murray Dave Schoenfeld Tom Sullivan Norma Bennett Partner Partner Partner Partner Of Counsel 202.639.5640 312.704.7766 312.704.7723 215.575.3130 713.546.5649 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SHOOK SHB.COM Melissa Sonali Jeanne Janchar Kali Backer Erin Bolden Nott Davis Gunawardhana Of Counsel Associate Associate Of Counsel Of Counsel 816.559.2170 303.285.5303 312.704.7716 617.531.1673 202.639.5643 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] John Constance Bria Davis Erika Dirk Emily Pedersen Lischen Reeves Associate Associate Associate Associate Associate 816.559.2017 816.559.0397 312.704.7768 816.559.2662 816.559.2056 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Katelyn Romeo Jon Studer Ever Tápia Matt Williams Associate Associate Vergara Associate 215.575.3114 312.704.7736 Associate 415.544.1932 [email protected] [email protected] 816.559.2946 [email protected] [email protected] ATLANTA | BOSTON | CHICAGO | DENVER | HOUSTON | KANSAS CITY | LONDON | LOS ANGELES MIAMI | ORANGE COUNTY | PHILADELPHIA | SAN FRANCISCO | SEATTLE | TAMPA | WASHINGTON, D.C. -

Fcm Regulations of the Clearing House Lch Limited

FCM REGULATIONS OF THE CLEARING HOUSE LCH LIMITED FCM Regulations Contents CONTENTS Regulation Page Regulation 1 Definitions ..................................................................................................... 2 (a) which the Clearing House and the Rates Exchange have agreed will be cleared in accordance with, and subject to, the Rates Exchange Rules and the FCM Rulebook via the FCM Listed Interest Rates Open Offer clearing mechanism (and not via novation under FCM Regulation 54); and ............ 27 (b) regardless of whether such match is described or characterised as a trade, transaction or agreement in the relevant Rates Exchange Rules. ................ 27 Chapter I - SCOPE ................................................................................................................... 33 Regulation 2 Obligations of the Clearing House to each FCM Clearing Member ........... 33 Regulation 3 Performance by the Clearing House of its Obligations under the Terms of an Open Contract; Novation ........................................................................ 34 Chapter II - STATUS ............................................................................................................... 35 Regulation 4 FCM Clearing Member Status and Application of LCH Regulations ......... 35 Regulation 5 Resigning and Retiring Members ................................................................ 38 Regulation 6 Service Withdrawal ...................................................................................... 40 Chapter -

Contract Basics for Litigators: Illinois by Diane Cafferata and Allison Huebert, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation

STATE Q&A Contract Basics for Litigators: Illinois by Diane Cafferata and Allison Huebert, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation Status: Law stated as of 01 Jun 2020 | Jurisdiction: Illinois, United States This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/w-022-7463 Request a free trial and demonstration at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/about/freetrial A Q&A guide to state law on contract principles and breach of contract issues under Illinois common law. This guide addresses contract formation, types of contracts, general contract construction rules, how to alter and terminate contracts, and how courts interpret and enforce dispute resolution clauses. This guide also addresses the basics of a breach of contract action, including the elements of the claim, the statute of limitations, common defenses, and the types of remedies available to the non-breaching party. Contract Formation to enter into a bargain, made in a manner that justifies another party’s understanding that its assent to that 1. What are the elements of a valid contract bargain is invited and will conclude it” (First 38, LLC v. NM Project Co., 2015 IL App (1st) 142680-U, ¶ 51 (unpublished in your jurisdiction? order under Ill. S. Ct. R. 23) (citing Black’s Law Dictionary 1113 (8th ed.2004) and Restatement (Second) of In Illinois, the elements necessary for a valid contract are: Contracts § 24 (1981))). • An offer. • An acceptance. Acceptance • Consideration. Under Illinois law, an acceptance occurs if the party assented to the essential terms contained in the • Ascertainable Material terms. -

Why Use Requirement Contracts? the Tradeoff Between Hold-Up And

Why Use Requirement Contracts? The Tradeoff between Hold-Up and Breach June 14, 2015 Eric Rasmusen Abstract A requirements contract is a form of exclusive dealing in which the buyer promises to buy only from one seller if he buys at all. This paper models a most common-sense motivation for such contracts: that the buyer wants to ensure a reliable supply at a pre- arranged price without any need for renegotiation or efficient breach. This requires that the buyer be unsure of his future demand, that a seller invest in capacity specific to the buyer, and that the transaction costs of revising or enforcing contracts be high. Transaction costs are key, because without them a better outcome can be obtained with a fixed- quantity contract. The fixed-quantity contract, however, requires breach and damages. If transaction costs make this too costly, an option contract does better. A requirements contract has the further advantage that it evens out the profits of the seller across states of the world and thus allows for an average price closer to marginal cost. Eric Rasmusen: John M. Olin Faculty Fellow, Olin Center, Harvard Law School; Visiting Professor, Economics Dept., Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts (till July 1, 2015). Dan R. and Catherine M. Dalton Professor, Department of Business Economics and Public Policy, Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, Bloomington Indiana. Eras- [email protected] or [email protected]. Phone: (812) 345-8573. Messaging: [email protected]. This paper: http://www.rasmusen.org/papers/holdup-rasmusen. pdf. Keywords: Hold-up problem, requirements contracts, relational contracting, exclusive dealing, expectation damages, option contracts, procurement, Uniform Commercial Code. -

Contracts 8 24

QUESTION 3 On Mayl, Buyer received the following letter: Dear Buyer: I have decided to give up my ranch and move to town. I thought that you might consider buying it from me. I will sell it to you for its current market value, $80,000. Call me by May 10. I will keep this proposal open, and will not withdraw it, until after that date. IS/ Seller The next day, Buyer mentioned to a friend, Mary, that he was considering buying the ranch. Mary responded that an acquaintance of hers, Jody, also had received an offer from Seller to purchase the ranch. Buyer immehately went home and prepared a letter of acceptance, addressed to Seller, and deposited it in the mail at 9:30 A.M. At 10:OO A.M. on May 2, Seller entered into a written agreement with Jody for the purchase of the ranch. At 2:00 P.M. on May 2, Buyer called Seller to arrange for a survey of the ranch. Seller informed Buyer that he had already sold the ranch. Upon hearing this, Buyer exclaimed, "We have a deal. I sent you an acceptance this morning by mail." QUESTION: Discuss whether there is a contract between Buyer and Seller and the basis for your conclusion. DISCUSSION FOR QUESTION 3 An offer is a manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain so made as to justify another person in understandmg that his assent to that bargain is invited and will conclude it. Res.2d Contracts 8 24. In this case Seller's letter is an offer, since under the objective test of intent, a reasonable person in Buyer's position would understand that Seller was in fact seeking Buyer's assent to his invitation. -

In Re First Phoenix

United States Bankruptcy Court Western District of Wisconsin Cite as: 575 B.R. 828 In re: First Phoenix-Weston, LLC, and FPG & LCD, L.L.C., Debtors Bankruptcy Case Nos. 16-12820-11 and 16-12821-11 (Jointly Administered) August 14, 2017 Justin M. Mertz, Esq., Michael Best & Friedrich LLP, Milwaukee, WI, for Debtors Frank W. DiCastri, Esq., Husch Blackwell LLP, Milwaukee, WI, for Creditor Catherine J. Furay, United States Bankruptcy Judge MEMORANDUM DECISION This is a tale of two views of the same transaction. Debtor First Phoenix-Weston, LLC (“Weston”) borrowed $14,694,599.73 from Sabra Phoenix TRS Venture, LLC (“Sabra Phoenix”) in November of 2013. The transaction was documented by a Loan Agreement, Note, and Mortgage. In addition, an Option Agreement was executed the same day between Weston and Sabra Phoenix. The Loan Agreement and related documents—including the Option Agreement—were assigned to Sabra Phoenix Wisconsin, LLC (“Sabra”) by Sabra Phoenix. On August 15, 2016, Weston and Co-Debtor FPG & LCD, L.L.C. (“FPG”) (collectively the “Debtors”), filed voluntary Chapter 11 petitions. On December 21, 2016, the Debtors’ largest pre-petition lender, Sabra, filed Proof of Claim No. 16 in the Weston case. The claim was in an amount “not less than” $17,773,438.77.1 The Proof of Claim contains an addendum detailing the calculation of the stated amount and, further, asserts “an unliquidated, unsecured amount as damages for Debtors’ pre-petition breach of the Option Agreement.” The Debtors objected to Sabra’s Proof of Claim No. 16 (“Claim Objection”). The objection focuses on the claim for additional sums related to the Option.2 Sabra moved “for Entry of Orders: (I) Estimating Claim for Breach of Option Agreement; and (II), to the Extent Necessary, Temporarily Allowing Sabra’s Claims for Voting Purposes” (the “Option Motion”). -

Application of the Uniform Commercial Code to Option Contracts for The

Campbell Law Review Volume 23 Article 4 Issue 1 Fall 2000 October 2000 Application of the Uniform Commercial Code to Option Contracts for the Sale of Goods, and Implying Promises to Find Sufficient Consideration: Why and How the North Carolina Supreme Court Got It Wrong in Fordham v. Eason James T. Newman Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.campbell.edu/clr Part of the Commercial Law Commons Recommended Citation James T. Newman Jr., Application of the Uniform Commercial Code to Option Contracts for the Sale of Goods, and Implying Promises to Find Sufficient Consideration: Why and How the North Carolina Supreme Court Got It Wrong in Fordham v. Eason, 23 Campbell L. Rev. 49 (2000). This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Campbell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. Newman: Application of the Uniform Commercial Code to Option Contracts fo Application of the Uniform Commercial Code to Option Con- tracts for the Sale of Goods, and Implying Promises to Find Suffi- cient Consideration: Why and How the North Carolina Supreme Court Got it Wrong in Fordham v. Eason* "Oft times members of both the bench and bar are criticized for failing to distinguish the forest from the trees. In this case, however, the con- troversy arises from an attempt to separate the trees from the forest."1 I. INTRODUCTION The North Carolina Supreme Court rarely ventures into cases involving contract disputes. -

A Consent Theory of Unconscionability: an Empirical Study of Law in Action Larry A

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository UF Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship Summer 2006 A Consent Theory of Unconscionability: An Empirical Study of Law in Action Larry A. DiMatteo University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Bruce L. Rich Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Contracts Commons Recommended Citation Larry A. DiMatteo & Bruce Louis Rich, A Consent Theory of Unconscionability: An Empirical Study of Law in Action, 33 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 1067 (2006), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/524 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UF Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONSENT THEORY OF UNCONSCIONABILITY: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF LAW IN ACTION LARRY A. DIMATTEO* & BRUCE LOUIS RICH** I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1068 II. DOCTRINE OF UNCONSCIONABILITY: LAW IN THE BOOKS .................................. 1070 A. The Procedural-SubstantiveBifurcation ................................................... 1072 B. Developing a FactorsAnalysis ................................................................... 1075 1. ProceduralFactors .............................................................................. -

Contract Formation Under Article 2 of the Uniform Commerical Code Carolyn M

Marquette Law Review Volume 61 Article 1 Issue 2 Winter 1977 Contract Formation Under Article 2 of the Uniform Commerical Code Carolyn M. Edwards Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Carolyn M. Edwards, Contract Formation Under Article 2 of the Uniform Commerical Code, 61 Marq. L. Rev. 215 (1977). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol61/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW Vol. 61 Winter 1977 No. 2 CONTRACT FORMULATION UNDER ARTICLE 2 OF THE UNIFORM COMMERCIAL CODE CAROLYN M. EDWARDS* Today, Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code' is the principal statute governing sales of goods2 in every state except Louisiana. Although the article made fundamental changes in the law of sales, it did not totally displace common law princi- ples. Indeed, some provisions of the statute codify common law rules. The shortcoming of the statute, however, is that it is not self-executing; it is silent on some issues and ambiguous as to others. Under these circumstances courts have resorted to com- mon law, citing Article 1, section 1-103,1 which provides that the principles of law and equity may supplement the Code unless such principles are displaced by particular provisions. * Assistant Professor of Law, Marquette University Law School; B.A. -

An Examination of Real Estate Purchase Options Ronald B

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Faculty Scholarship Shepard Broad College of Law Fall 1987 An Examination of Real Estate Purchase Options Ronald B. Brown Nova Southeastern University - Shepard Broad Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/law_facarticles Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons NSUWorks Citation Ronald B. Brown, An Examination of Real Estate Purchase Options, 12 NOVA L. REV. 147 (1987), Available at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/law_facarticles/106 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Shepard Broad College of Law at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: Ronald Benton Brown, An Examination of Real Estate Purchase Options, 12 Nova. L. Rev. 147 (1987) Provided by: NSU Shepard Broad College of Law Panza Maurer Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Fri Sep 21 09:17:44 2018 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device An Examination of Real Estate Purchase Options * Ronald Benton Brown TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: THE NATURE OF REAL ESTATE PURCHASE OPTIONS ........................... 147 II. CREATING A PURCHASE OPTION ................... -

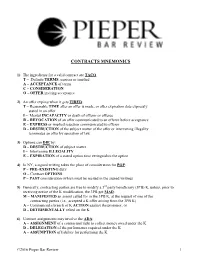

Contracts Mnemonics

CONTRACTS MNEMONICS 1) The ingredients for a valid contract are TACO: T – Definite TERMS, express or implied A – ACCEPTANCE of terms C – CONSIDERATION O – OFFER inviting acceptance 2) An offer expires when it gets TIRED: T – Reasonable TIME after an offer is made, or after expiration date expressly stated in an offer I – Mental INCAPACITY or death of offeror or offeree R – REVOCATION of an offer communicated to an offeree before acceptance E – EXPRESS or implied rejection communicated to offeror D – DESTRUCTION of the subject matter of the offer or intervening illegality terminates an offer by operation of law 3) Options can DIE by: D – DESTRUCTION of subject matter I – Intervening ILLEGALITY E – EXPIRATION of a stated option time extinguishes the option 4) In NY, a signed writing takes the place of consideration for POP: P – PRE–EXISTING duty O – Contract OPTIONS P – PAST consideration (which must be recited in the signed writing) 5) Generally, contracting parties are free to modify a 3rd party beneficiary (3PB) K, unless, prior to receiving notice of the K modification, the 3PB got MAD: M – MANIFESTED an assent called for in the 3PB K, at the request of one of the contracting parties (i.e., accepted a K offer arising from the 3PB K) A – Commenced a breach of K ACTION against the promisor, or D – DETRIMENTALLY relied on the K 6) Contract assignments may involve the ADA: A – ASSIGNMENT of a contractual right to collect money owed under the K D – DELEGATION of the performance required under the K A – ASSUMPTION of liability for performing