Blackness Castle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Palaces & Castles

PALACESPALACES, & Castles were built for wealthy people to live in. As so many wealthy people lived in castles, there were usually lots of lovely things that CASTLESCASTLES people wanted to steal. Sometimes enemies wanted the whole castle! Because of this, it was very important that castles were protected against enemies. Let’s find out more about parts of the castles that we would be able to see in Scotland! Then try the quiz on page 8! LINLITHGOW PALACE Can you spot ? The bailey It was a courtyard in the middle of the castle. It was a large piece of open ground. Arrow loops, or slits, They were used to defend the castle from invaders. These narrow slits were cut into the stone walls and used to shoot arrows through. The flying arrows would come as a big surprise to the invaders down below! Linlithgow Palace STIRLING CASTLE Can you spot ? The gatehouse The gatehouse was a strong building built over the gateway. The barbican The barbican was a wall which jutted out around the gateway or might be like a tower. Its main job was to add strength to the gatehouse. The battlement Battlements were basically small defensive walls at the top of a castles main walls with gaps to fire arrows through. EDINBURGH CASTLE The portcullis A portcullis is a heavy gate that was lowered down by chains from above the gateway. It comes from a French words ‘porte coulissante,’ which means sliding door. DIRLETON CASLTLE Murder Holes They are holes or gaps above a castle’s doorway to drop things on anyone trying to come in uninvited. -

Outlander-Itinerary-Trade.Pdf

Outlander Based on the novels by Diana Gabaldon, this historical romantic drama has been brought to life on-screen with passion and verve and has taken the TV Doune Castle world by storm. The story begins in 1945 when WWII nurse Claire Randall, on a second honeymoon in the Scottish Highlands with her husband Frank, is transported back to 1743 where she encounters civil war and dashing Scottish warrior Jamie Fraser. Follow in the footsteps of Claire and Jamie and visit some of Scotland’s most iconic heritage attractions. Linlithgow Palace Aberdour Castle Blackness Castle www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/outlander Ideal for groups or individuals visiting a number of properties, holders can access as many Historic Scotland sites as they wish which includes a further 70 sites in addition to those in our itineraries. Passes Outlander is a fascinating story that combines fantasy, can be used as part of a package or offered as an romance and adventure showcasing Scotland’s rich N optional add-on. landscape and dramatic history in the process.Shetland 150 miles Our Explorer Pass makes it simple to travel around the sites – Includes access to all 78 Historic Scotland attractions that feature both in the novels and television series and – 20% commission on all sales offers excellent value for money. Below we have suggested – Flexible Entry Times itineraries suitable for use with our 3 or 7 day pass. 7 Seven day itinerary 6 1 5 Day 1 Doune Castle (see 3 day itinerary) 2 Day 2 Blackness Castle (see 3 day itinerary) 3 Day 3 Linlithgow Palace (see 3 day itinerary) 4 Aberdour Castle and Gardens 1 4 Day 4 3 2 This splendid ruin on the Fife Coast was the luxurious Renaissance home of Regent Morton, once Scotland’s most powerful man. -

Download Food & Drink Experiences Itinerary

Food and Drink Experiences TRAVEL TRADE Love East Lothian These itinerary ideas focus around great traditional Scottish hospitality, key experiences and meal stops so important to any trip. There is an abundance of coffee and cake havens, quirky venues, award winning bakers, fresh lobster and above all a pride in quality and in using ingredients locally from the fertile farm land and sea. The region boasts Michelin rated restaurants, a whisky distillery, Scotland’s oldest brewery, and several great artisan breweries too. Scotland has a history of gin making and one of the best is local from the NB Distillery. Four East Lothian restaurants celebrate Michelin rated status, The Creel, Dunbar; Osteria, North Berwick; as well as The Bonnie Badger and La Potiniere both in Gullane, recognising East Lothian among the top quality food and drink destinations in Scotland. Group options are well catered for in the region with a variety of welcoming venues from The Marine Hotel in North Berwick to Dunbar Garden Centre to The Prestoungrange Gothenburg pub and brewery in Prestonpans and many other pubs and inns in our towns and villages. visiteastlothian.org TRAVEL TRADE East Lothian Larder - making and tasting Sample some of Scotland’s East Lothian is proudly Scotland’s Markets, Farm Shops Sample our fish and seafood Whisky, Distilleries very best drinks at distilleries Food and Drink County. With a and Delis Our coastal towns all serve fish and and breweries. Glimpse their collection of producers who are chips, and they always taste best by importance in Scotland’s passionate about their products Markets and local farm stores the sea. -

Macg 1975Pilgrim Web.Pdf

-P L L eN cc J {!6 ''1 { N1 ( . ~ 11,t; . MACGRl!OOR BICENTDmIAL PILGRIMAGE TO SCOTLAND October 4-18, 197.5 sponsored by '!'he American Clan Gregor Society, Inc. HIS'lORICAL HIGHLIGHTS ABO ITINERARY by Dr. Charles G. Kurz and Claire MacGregor sessford Kurz , Art work by Sue S. Macgregor under direction of R. James Macgregor, Chairman MacGregor Bicentennial Pilgrimage booklets courtesy of W. William Struck, President Ambassador Travel Service Bethesda, Md • . _:.I ., (JUI lm{; OJ. >-. 8IaIYAt~~ ~~~~ " ~~f. ~ - ~ ~~.......... .,.; .... -~ - 5 ~Mll~~~. -....... r :I'~ ~--f--- ' ~ f 1 F £' A:t::~"r:: ~ 1I~ ~ IftlC.OW )yo X, 1.. 0 GLASGOw' FOREWORD '!hese notes were prepared with primary emphasis on MaoGregor and Magruder names and sites and their role in Soottish history. Secondary emphasis is on giving a broad soope of Soottish history from the Celtio past, inoluding some of the prominent names and plaoes that are "musts" in touring Sootland. '!he sequenoe follows the Pilgrimage itinerary developed by R. James Maogregor and SUe S. Maogregor. Tour schedule time will lim t , the number of visiting stops. Notes on many by-passed plaoes are information for enroute reading ani stimulation, of disoussion with your A.C.G.S. tour bus eaptain. ' As it is not possible to oompletely cover the span of Scottish history and romance, it is expected that MacGregor Pilgrims will supplement this material with souvenir books. However. these notes attempt to correct errors about the MaoGregors that many tour books include as romantic gloss. October 1975 C.G.K. HIGlU.IGHTS MACGREGOR BICmTENNIAL PILGRIMAGE TO SCOTLAND OCTOBER 4-18, 1975 Sunday, October 5, 1975 Prestwick Airport Gateway to the Scottish Lowlands, to Ayrshire and the country of Robert Burns. -

13 Consultation on Planning Guidance for Wind Farms Over 12

REPORT TO: Cabinet MEETING DATE: 12 March 2013 BY: Executive Director (Services for Communities) SUBJECT: Consultation on Planning Guidance for Windfarms of over 12 Megawatts 1 PURPOSE 1.1 To advise Cabinet (i) of the preparation of draft planning guidance intended to provide a spatial framework against which proposals for wind farms of 12MW output and more will be assessed and (ii) to seek Cabinet approval to take the draft Guidance on Wind Turbines over 12MW appended to this report, to public consultation. 2 RECOMMENDATION 2.1 That Cabinet approve the attached report, Guidance on Windfarms Over 12MW, for public consultation. 3 BACKGROUND 3.1 East Lothian Council already has large scale wind turbine development at Crystal Rig (191MW in total) and Aikengall (48MW). Consent has been given for development at Pogbie (now under construction), and at Keith Hill. An application at Wester Dod, Monynut, is under consideration by Scottish Ministers. Existing wind development outwith the East Lothian Council area can also have substantial visual effects, for example, at Fallago Rig (currently under construction) and Dun Law. There is also just under 2MW of smaller wind development consented in East Lothian. 3.2 The Scottish Government, through Scottish Planning Policy, requires Councils to produce a spatial framework for windfarms of over 20MW for their areas. There is scope to incorporate windfarms of less than this if it is considered appropriate. In East Lothian, current policy on wind turbine development is contained within the East Lothian Local Plan. The Council has also commissioned the Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Turbine Development in East Lothian (2005), supplemented by the more recent East Lothian Supplementary Landscape Capacity Study for Smaller Wind Turbines (2011). -

Looking at Marie De Guise

Looking at Marie de Guise https://journals.openedition.org/episteme/8092 Tout OpenEdition Revue de littérature et de civilisation (XVIe – XVIIIe siècles) 37 | 2020 Marie de Guise et les transferts culturels / Contingence et fictions de faits divers Marie de Guise and Cultural Transfers Looking at Marie de Guise Regards sur Marie de Guise S R https://doi.org/10.4000/episteme.8092 Résumés English Français This paper examines the symbolic value of the headdresses worn by French women at the Scottish court following the marriage of James V and Mary de Guise in 1538, using the Stirling Heads, portrait medallions from the Renaissance palace at Stirling Castle, as visual evidence. While several of the women are portrayed wearing a conventional French hood, others, including Marie de Guise, wear elaborately crafted “chafferons” which would have been made of gold wire. The chafferon is an unusual choice of headdress for a portrait and the reasons for this are considered with reference to the Petrarchan canon of ideal female beauty and how precious metal and shining hair merged into a single visual conceit. The royal accounts show that chafferons worn by the gentlewomen at the Scottish court were exceptional gifts made by the royal goldsmiths using Scottish gold from the king’s own mines, extracted with the assistance of miners sent by the Duke and Duchess of Guise. These chafferons, therefore, carried layers of meaning about the transformation of Scotland’s fortunes through dynastic marriage and the promise of a new Golden Age of peace and prosperity. Cet article, qui étudie la valeur symbolique des coiffes portées par les femmes françaises à la cour d’Écosse après le mariage de Jacques V et de Marie de Guise en 1538, utilise comme preuves matérielles des portraits gravés sur des médaillons de bois ornant le palais Renaissance du château de Stirling et connus sous le nom de Stirling Heads. -

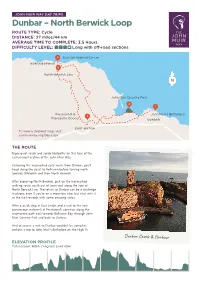

North Berwick Loop ROUTE TYPE: Cycle DISTANCE: 27 Miles/44 Km AVERAGE TIME to COMPLETE: 3.5 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Long with Off-Road Sections

JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Dunbar – North Berwick Loop ROUTE TYPE: Cycle DISTANCE: 27 miles/44 km AVERAGE TIME TO COMPLETE: 3.5 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Long with off-road sections 4 Scottish Seabird Centre NORTH BERWICK 5 North Berwick Law John Muir Country Park 2 1 Prestonmill & John Muir’s Birthplace 3 Phantassie Doocot DUNBAR EAST LINTON To view a detailed map, visit joinmuirway.org/day-trips THE ROUTE Enjoy quiet roads and sandy footpaths on this tour of the easternmost section of the John Muir Way. Following the waymarked cycle route from Dunbar, you’ll head along the coast to Belhaven before turning north towards Whitekirk and then North Berwick. After exploring North Berwick, pick up the waymarked walking route south out of town and along the foot of North Berwick Law. The return to Dunbar can be a challenge in places, even if you’re on a mountain bike, but stick with it as the trail rewards with some amazing vistas. After a quick stop in East Linton and a visit to the very picturesque watermill at Prestonmill, continue along the waymarked path east towards Belhaven Bay, through John Muir Country Park and back to Dunbar. And of course a visit to Dunbar wouldn’t be complete without a trip to John Muir’s Birthplace on the High St. Dunbar Castle & Harbour ELEVATION PROFILE Total ascent 369m / Highest point 69m JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Dunbar - North Berwick Loop PLACES OF INTEREST 1 JOHN MUIR’S BIRTHPLACE Pioneering conservationist, writer, explorer, botanist, geologist and inventor. Discover the many sides to John Muir in this museum located in the house where he grew up. -

SCOTLAND and the BRITISH ARMY C.1700-C.1750

SCOTLAND AND THE BRITISH ARMY c.1700-c.1750 By VICTORIA HENSHAW A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The historiography of Scotland and the British army in the eighteenth century largely concerns the suppression of the Jacobite risings – especially that of 1745-6 – and the growing assimilation of Highland soldiers into its ranks during and after the Seven Years War. However, this excludes the other roles and purposes of the British army, the contribution of Lowlanders to the British army and the military involvement of Scots of all origin in the British army prior to the dramatic increase in Scottish recruitment in the 1750s. This thesis redresses this imbalance towards Jacobite suppression by examining the place of Scotland and the role of Highland and Lowland Scots in the British army during the first half of the eighteenth century, at a time of change fuelled by the Union of 1707 and the Jacobite rebellions of the period. -

Highland Tours 2019-2020 Edinburgh Departures We Also Depart from Glasgow and Inverness

Highland Tours 2019-2020 Edinburgh departures We also depart from Glasgow and Inverness 1, 2, 3 and 5 day tours for groups and independent travellers Call us on: 0131 226 6066 (07:00 - 22:00 daily) www.timberbushtours.com BOOK TODAY, TRAVEL TOMORROW Let Scotland inspire you. Book today, travel tomorrow. Timberbush Tours heißt Sie Timberbush Tours vous souhaite la Timberbush Tours deseja a você herzlich in Schottland willkommen! bienvenue en Écosse ! Nous vous um caloroso bem-vindo à Escócia! Begleiten Sie uns auf einer unserer invitons à découvrir l’Écosse tout au long Descubra o cenário emocionante das 1-5-tägigen 5-Sterne-Touren und entdecken de nos visites guidées 5 étoiles. Durant 1-5 Highlands (as Terras Altas) e das ilhas Sie die atemberaubende Landschaft der jours vous verrez les Highlands et les îles escocesas, escolhendo um de nossos schottischen Highlands und Inseln. Unsere écossaises avec leurs paysages à couper le maravilhosos passeios de 1-5 dias. Nossos erfahrenen und freundlichen Reiseleiter souffle. Nos guides expérimentés et plein simpáticos guias são expertos contadores sind fantastische Geschichtenerzähler, d’entrain sont de fantastiques conteurs ; en de fantásticas histórias e levarão você para die die Geschichte Schottlands, seiner leur compagnie vous revivrez l’histoire de uma jornada de descoberta da Escócia, com Menschen und Kulturen lebendig werden l’Écosse, de ses habitants et l’esprit écossais a sua história, povo e cultura, a bordo de lassen, während Sie in einem luxuriösen vous sera dévoilé. Ils vous accompagneront um luxuoso ônibus Mercedes Benz. Em MercedesBenz-Reisebus durch die Highlands dans les Highlands à bord de notre autocar nossos passeios, você vai ter muito tempo reisen. -

Sites-Guide.Pdf

EXPLORE SCOTLAND 77 fascinating historic places just waiting to be explored | 3 DISCOVER STORIES historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place OF PEOPLE, PLACES & POWER Over 5,000 years of history tell the story of a nation. See brochs, castles, palaces, abbeys, towers and tombs. Explore Historic Scotland with your personal guide to our nation’s finest historic places. When you’re out and about exploring you may want to download our free Historic Scotland app to give you the latest site updates direct to your phone. ICONIC ATTRACTIONS Edinburgh Castle, Iona Abbey, Skara Brae – just some of the famous attractions in our care. Each of our sites offers a glimpse of the past and tells the story of the people who shaped a nation. EVENTS ALL OVER SCOTLAND This year, yet again we have a bumper events programme with Spectacular Jousting at two locations in the summer, and the return of festive favourites in December. With fantastic interpretation thrown in, there’s lots of opportunities to get involved. Enjoy access to all Historic Scotland attractions with our great value Explorer Pass – see the back cover for more details. EDINBURGH AND THE LOTHIANS | 5 Must See Attraction EDINBURGH AND THE LOTHIANS EDINBURGH CASTLE No trip to Scotland’s capital is complete without a visit to Edinburgh Castle. Part of The Old and New Towns 6 EDINBURGH CASTLE of Edinburgh World Heritage Site and standing A mighty fortress, the defender of the nation and majestically on top of a 340 million-year-old extinct a world-famous visitor attraction – Edinburgh Castle volcano, the castle is a powerful national symbol. -

The History of the Second Dragoons : "Royal Scots Greys"

Si*S:i: \ l:;i| THE HISTORY OF THE SECOND DRAGOONS "Royal Scots Greys" THE HISTORY OF THE SECOND DRAGOONS 99 "Royal Scots Greys "•' •••• '-•: :.'': BY EDWARD ALMACK, F.S.A. ^/>/4 Forty-four Illustrations LONDON 1908 ^7As LIST OF SUBSCRIBERS. Aberdeen University Library, per P. J. Messrs. Cazenove & Son, London, W.C. Anderson, Esq., Librarian Major Edward F. Coates, M.P., Tayles Edward Almack, Esq., F.S.A. Hill, Ewell, Surrey Mrs. E. Almack Major W. F. Collins, Royal Scots Greys E. P. Almack, Esq., R.F.A. W. J. Collins, Esq., Royal Scots Greys Miss V. A. B. Almack Capt. H.R.H. Prince Arthur of Con- Miss G. E. C. Almack naught, K.G., G.C.V.O., Royal Scots W. W. C. Almack, Esq. Greys Charles W. Almack, Esq. The Hon. Henry H. Dalrymple, Loch- Army & Navy Stores, Ltd., London, S.W. inch, Castle Kennedy, Wigtonshire Lieut.-Col. Ash BURNER, late Queen's Bays Cyril Davenport, Esq., F.S.A. His Grace The Duke of Atholl, K.T., J. Barrington Deacon, Esq., Royal etc., etc. Western Yacht Club, Plymouth C. B. Balfour, Esq. Messrs. Douglas & Foulis, Booksellers, G. F. Barwick, Esq., Superintendent, Edinburgh Reading Room, British Museum E. H. Druce, Esq. Lieut. E. H. Scots Bonham, Royal Greys Second Lieut. Viscount Ebrington, Royal Lieut. M. Scots Borwick, Royal Greys Scots Greys Messrs. Bowering & Co., Booksellers, Mr. Francis Edwards, Bookseller, Lon- Plymouth don, W. Mr. W. Brown, Bookseller, Edinburgh Lord Eglinton, Eglinton Castle, Irvine, Major C. B. Bulkeley-Johnson, Royal N.B. Scots Greys Lieut. T. E. Estcourt, Royal Scots Greys 9573G5 VI.