L \I;A 1 5Q (' A:S IOFFICIAL] II a 1:21 ') , Jl11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tauranga Open Cross Country 29Th May 2021 Club House Finish Waipuna Park Wet

Tauranga Open Cross Country 29th May 2021 Club House Finish Waipuna Park Wet Position Grade PositionFirst Name Last Name Grade Time School (if applicable) Town / City Club Masters Men #8km 15 1 Sjors Corporaal MM35 26:57 Rotorua Lake City Athletics 17 2 Steve Rees-Jones MM35 28:18 Cambridge Hamilton City Hawks 18 3 Iain Macdonald MM35 29:21 Rotorua Lake City Athletics Club 22 4 Dean Chiplin MM35 29:59 Cambridge Cambridge Athletic & Harrier Club 23 5 Matthew Parsonage MM35 30:04 Rotorua Lake City Athletics Club 26 6 Brad Dixon MM35 31:05 Tauranga Tauranga 28 7 Andrew Vane MM35 31:22 Tauranga Tauranga Ramblers 29 8 John Charlton MM35 31:40 Hamilton Cambridge Athletic & Harrier Club 31 9 Adam Hazlett MM35 32:26 Tauranga 32 10 Stewart Simpson MM35 32:41 Tauranga Tauranga Ramblers 33 11 Mike Harris MM35 32:45 Hamilton Hamilton Hawks 34 12 Joe Mace MM35 32:57 Hamilton Hamilton Hawks 35 13 Andrew Twiddal MM35 33:40 Rotorua Lake City 36 14 Benjamin Tallon MM35 34:04 Tauranga 37 15 John Caie MM35 34:17 Tauranga Tauranga Ramblers 38 16 Alan Crombie MM35 35:08 Rotorua Lake City Athletics Club 39 17 Michael Craig MM35 35:22 Tauranga Tauranga 40 18 Mark Handley MM35 35:49 Tauranga Tauranga Ramblers 43 19 Terry Furmage MM35 37:03 Tauranga Tauranga Ramblers Masters Men #6km Position Grade PositionFirst Name Last Name Grade Time School (if applicable) Town / City Club 19 1 Gavin Smith MM65 29:21 Tauranga Athletics Tauranga Inc 24 2 Trevor Ogilvie MM65 30:14 Rotorua Lake City Athletics Club 41 3 David Griffith MM65 36:01 Cambridge Cambridge Athletic & -

Identification of Outstanding Natural Features and Landscapes Otamataha - Misson Cemetery

part three Identification of Outstanding Natural Features and Landscapes Otamataha - Misson Cemetery Description: Located on the edge of central Tauranga, Otamataha comprises the remnant headland known as Te Papa. Prior to the reclamation of Sulphur Point and Chapel Street, Otamataha formed the headland to this part of Tauranga. Historically a Pa for Ngati Maru, the site became the Mission Cemetery and contains the earliest Pakeha graves in Tauranga. The site holds significant historical values to the City and has been recognised as such in the recently adopted Historic Reserves Management Plan (December 2008). The landscape surrounding and within the landscape feature has been significantly altered through infrastructure and transit based development. The Tauranga bridge and associated roading connections extend around the periphery of the site, resulting in the loss of natural features and landform. To the south of the site the new Sebel Hotel complex sits immediately adjacent to the site, and screens much of the site’s edge from view from the CBD area. Significant landscape features of the site comprise the remnant pohutukawa along the seaward edge and a significant stand of exotic specimen trees. The raised cliff edge and vegetation cover extends above the water’s edge and the Sebel Hotel, creating visual connection between the site and central Tauranga. Core Values: • Moderate natural science values associated with the remaining geomorphological values. • Moderate representative values due to the location and vegetation patterns. • Moderate shared and recognised values at a City level. • High historical values due to its sigificant archaeological features and heritage values. • Moderate aesthetic values associated with vegetation patterns along the harbour edge. -

Mount Maunganui, Omanu

WhakahouTaketake VitalUpdate TAURANGA 2020 Snapshot Mount Maunganui, Omanu Photo credit: Tauranga City Council Ngā Kaiurupare: Respondents This page represents the demographics of the 449 survey respondents who reside in Mount Maunganui and Omanu. Age groups Mount Maunganui, Omanu 16–24 25–44 45–64 65+ years years years years 11% 36% 32% 21% Ethnic groups Gender NZ European 90% Māori 11% 49% 51% Asian 3% Pacific 1% Unemployment rate Middle Eastern, Latin American, 2% African Unemployment rate in Mount Maunganui and Omanu is lower than the average in Tauranga Other 1% (5.1%). It is still slightly higher than the National average at 4%(1). 48 out of 449 respondents identified as 4.5% belonging to more than one Ethnic group NOTES: 1 https://www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/unemployment-rate 2 Sample: n=449. Whakahou Taketake Vital Update | TAURANGA 2020 2 Ngā Kaiurupare: Respondents % from all respondents Ethnicity (Multiple choice) 9% 499 NZ European 89.9% Māori 10.6% Length of time lived in Tauranga Asian 2.8% Less than 1 year 4.3% Pacific 1.2% 1 - 2 years 7.7% Middle Eastern, Latin American, 2.1% African 3 - 5 years 15.7% Other 0.8% 6 - 10 years 10.5% More than 10 years 43.6% Employment status (Multiple choice) I have lived here on and off 18.2% throughout my life At school / study 9.3% Self employed 2.2% Gender Disability benefit / ACC / Sickness 0.7% Male 48.6% Stay at home Mum / Parental leave / 1.7% Homemaker Female 51.4% Business owner 0.5% Unemployed 4.5% Age Unpaid worker / internship / apprenticeship 0.7% 16 - 24 11.4% Casual/seasonal worker 2.0% 25 - 34 19.9% Work part-time 14.5% 35 - 44 15.9% Work full-time 49.6% 45 - 54 15.9% Retired 20.0% 55 - 64 16.4% Volunteer 6.4% 65 - 74 11.4% Other 0.2% 75 - 84 6.5% 85+ 2.7% Disabilities Disabled people 11.1% NOTES: People who care for a disabled person 4.5% 1. -

Ben Davies, Water Network Planning Discipline Lead, MWH, Now Part of Stantec, Wellington

GHOST HUNTING WATER NETWORK MODELLING TO FIND A PHANTOM BURST Ben Davies, Water Network Planning Discipline Lead, MWH, now part of Stantec, Wellington Abstract Between 24 and 26 January 2016, there was a sudden drop in both the Mangatawa and Mount Maunganui reservoirs, which feed the Coastal Strip water supply network in Tauranga. The system was already at peak summer demand, and the drop in reservoir levels equated to a further 100 l/s demand on the network. The Coastal Strip network includes Tauranga’s heavy industrial area, along with the Port of Tauranga. The idea of this area going dry would give any water network manager nightmares. As the reservoir levels continued to drop, the water model was used to confirm stop-gap operational measures, which were then put in place to stop the network going dry. The unknown demand slowly disappeared over the next couple of days, and system operation returned to normal. Although the immediate danger appeared to be over, the cause of this large temporary drain on the network remained unknown, and there was a risk it could occur again at any time. MWH and TCC have worked together for a number of years to develop a good operational water model. Once the dust had settled, TCC asked MWH to undertake an analysis using the hydraulic water network model to look at the event in detail. This paper outlines how innovative water modelling techniques and collaboration between TCC and MWH were used to find the 100 l/s ghost, and restore the resilience of the Coastal Strip water network. -

The Archaeology of Matakana Island

1 THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL OF MATAKANA ISLAND REPORT PREPARED FOR WESTERN BAY OF PLENTY DISTRICT COUNCIL AND OTHERS BY KEN PHILLIPS (MA HONS) AUGUST 2011 ARCHAEOLOGY B.O.P. Heritage Consultants P O Box 855 Whakatane PHONE: 027 276 9919 EMAIL: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Project Background 3 Matakana Island 3 Resource Management Act 1991 3 New Zealand Historic Places Act 1993 4 Constraints and Limitations 4 METHODOLOGY 5 PHYSICAL LANDSCAPE 5 Geology 5 Soils 6 Vegetation 6 ARCHAEOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE 7 Previous Archaeological Research 7 Site Inventory 8 Archaeological Sites on the Barrier Dunes 10 Pa 10 Midden 10 Archaeological Sites on the Bulge and Rangiwaea Island 12 Pa 12 Undefended settlement and cultivation sites 14 Antiquity of Settlement of Matakana Island 16 Radiocarbon dates 16 Archaic settlement on Matakana Island13th – 15th Century 17 th th 16 – 19 Century 19 DISCUSSION 20 Archaeological Significance 20 The Bulge and Rangiwaea 20 The Barrier Dunes 20 Current Threats 21 RECOMMENDATIONS 22 BIBLIOGRAPHY 23 APPENDIX A: Topographic Map showing location and NZAA numbers of recorded archaeological sites on Matakana Island. 3 INTRODUCTION Project Background This archaeological report was commissioned by Western Bay of Plenty District Council in order to provide an overview of the archaeological resource on Matakana Island and forms part of the whole of island plan for Matakana Island in accordance with the Regional Policy Statement. The Regional Policy Statement states that Council shall: 17A.4(iv) Investigate a future land use and subdivision pattern for Matakana Island, including papakainga development, through a comprehensive whole of Island study which addresses amongst other matters cultural values, land which should be protected from development because of natural or cultural values and constraints, and areas which may be suitable for small scale rural settlement, lifestyle purposes or limited Urban Activities. -

Metroport Inland Port, New Zealand

39 5 MetroPort Inland Port, New Zealand 5.1 Port of Tauranga 5.1.1 Ownership structure, location and history The Port of Tauranga, situated at Mount Maunganui on New Zealand’s North Island, emerged in the mid 1950s, mainly servicing the fledgling log export industry. As time has passed, the port has also played a major role in the export of locally produced dairy products and fruit. Much of this business was in conventional ships until the creation of the Sulphur Point container facility in the mid 1990s, when a two crane facility was opened. Its position near Auckland means Tauranga is the second largest container handling port in the country, with recent growth occurring as a result of decisions by shipping companies to use its intermodal MetroPort facility and a policy change by the dairy industry to use ports that are near to the product source. The port is quoted on the NZ Stock Exchange, with 45 per cent of its shares publicly tradable. The remainder are held by a local regional council under a nominee company. Throughput sees Tauranga handling 23 per cent of the nation’s containers (Auckland 45 per cent), 30 per cent of export tonnage (10 per cent) and 12 per cent of import tonnage (22 per cent). Tauranga has also diversified, with a 50/50 joint venture holding in the timber export port of Northport and an advisory input to the Port of Marlborough. 5.1.2 Driving forces According to the Business Development Manager at the Port of Tauranga: In the 1960s and 1970s the New Zealand container terminals were established in the four main commercial centres at that time – Auckland, Wellington, Lyttleton and Dunedin. -

Mt Maunganui North Ultrafast Fibre Installation (HNZPTA Authority 2014/1028)

Mt Maunganui North Ultrafast Fibre installation (HNZPTA authority 2014/1028) report to Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga and Transfield Services Ltd Peter Holmes, Arden Cruickshank and Matthew Campbell CFG Heritage Ltd. P.O. Box 10 015 Dominion Road Auckland 1024 ph. (09) 309 2426 [email protected] Mt Maunganui North Ultrafast Fibre installation (HNZPTA authority 2014/1028) report to Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga and Transfield Services Ltd Prepared by: Peter Holmes Reviewed by: Date: 6 July 2014 Jacqueline Craig Reference: 13-0530 This report is made available by CFG Heritage Ltd under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/. CFG Heritage Ltd. P.O. Box 10 015 Dominion Road Auckland 1024 ph. (09) 309 2426 [email protected] This report is supplied electronically Please consider the environment before printing Hard copy distribution Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, Tauranga Transfield Services Ltd New Zealand Archaeological Association (file copy) CFG Heritage Ltd (file copy) University of Auckland General Library University of Otago Anthropology Department Ngai Tukairangi Mt Maunganui North Ultrafast Fibre installation (HNZPTA authority 2014/1028) Peter Holmes, Arden Cruickshank and Matthew Campbell Transfield Services has undertaken the underground installation of Ultrafast Fibre throughout the Mt Maunganui North area as part of the nationwide rollout. Two archaeological sites were previously recorded in the New Zealand Archaeological Association (NZAA) Site Recording Scheme (SRS) in the project area: U14/369, Waikoriri / Pilot Bay; and U14/429, Hopu Kiore / Mt Drury. Transfield commis- sioned an archaeological assessment of the project area (Campbell and Holmes 2014) and applied to the New Zealand Historic Places Trust (now Heritage New 1. -

Ledlenser Tauranga 14Km Night Run/Walk Ledlenser Tauranga 21.1

Ledlenser Tauranga 14km Night Run/Walk Place First Name Surname Gender Town Time 1 Scott Carley Male Tauranga 0:59:17 2 Adam Bentley Male Ellerslie 1:07:40 3 David Hintz Male Rotorua 1:13:47 4 Andrew Brown Male Papamoa Beach 1:15:07 5 Emily Corin Female Otorohanga 1:18:17 6 John Duncan Male Hamilton 1:18:59 7 Stuart Mcadam Male Hamilton 1:19:38 8 Peter Mcluckie Male Tauranga 1:21:09 9 Dana Signal Female Matua 1:22:54 10 Andrew Hedge Male Havelock North 1:23:13 11 Simon Belworthy Male Thames 1:25:43 12 Olivia Harris Female Rotorua 1:26:17 13 Paul Lyttle Male Tauranga 1:26:22 14 Sarah Kraayvanger Female Te Awamutu 1:28:58 15 Michael Gawthorne Male Mount Maunganui South 1:32:48 16 Steve Parsons Male Papamoa 1:38:10 17 Trinity Sarten Female Tauranga 1:38:12 18 John Crimmins Male Tauranga 1:38:14 19 Lara Beetham Female Marton 1:38:48 20 Jonathan Beetham Male Marton 1:38:50 21 Claire Bentley Female Ellerslie 1:39:00 22 Victoria Wicks-Brown Female Tauranga 1:39:22 23 Kelly Taylor Female Tauranga 1:39:22 24 Kirsten Nicholson Female Tauranga 1:39:23 25 Blake Loftus-Cloke Female Tauranga 1:39:23 26 Andrea Young Female Tauranga 1:39:25 27 Helen Giles Female Papamoa 1:44:58 28 Anita Bishop Female Hamilton 1:47:29 29 Savanna Eva Female Te Awamutu 1:47:30 30 Graeme Leggett Male Tauranga 1:53:52 31 Jen Permain Female Tokoroa 1:56:45 32 Hayley Edwards Female Tokoroa 1:56:47 33 Wendy Gillespie Female Tauranga 1:58:37 34 Rebecca Rogers Female Papamoa Beach 1:59:41 35 Tessa Honeyfield Female Te Awamutu 2:13:34 36 Jacqui Ryan Female Te Awamutu 2:13:40 37 -

Port Operational Information

Port Operational Information S:\Port Information\Port Operational Information Document Controller: Marketing and Customer Support July 2015 S:\Port Information\Port Operational Information Document Controller: Marketing and Customer Support July 2015 S:\Port Information\Port Operational Information Document Controller: Marketing and Customer Support July 2015 METROPORT AUCKLAND – A PORT WITHOUT WATER MetroPort Auckland, situated in the heart of South Auckland’s manufacturing area, is the country’s first inland dry port. The facility is part of a totally integrated transport system, linking the expertise and services of the Port and KiwiRail. The Port of Tauranga is New Zealand’s largest export port by volume, and has long been recognised as centre of positive change within the port sector. KiwiRail, New Zealand’s leading transport company provides the rail link between Tauranga and MetroPort. A logical integration of services forms the basis of MetroPort Auckland’s operations. When a shipping line, which is contracted to use MetroPort, calls at the Port of Tauranga, import cargo destined for Auckland is offloaded at the Tauranga Container Terminal, and railed to MetroPort Auckland. From there it is distributed to its final destination. The same process happens in reverse for Auckland sourced export cargo. It is aggregated at MetroPort Auckland; railed to Tauranga; and loaded onto the vessel. MetroPort Auckland offers a range of practical benefits to shipping lines, exporters and importers including: a choice of ports in the Auckland region efficient tracking of cargo through state of the art information technology guaranteed cargo delivery times direct delivery into South Auckland without having to rely on central Auckland’s heavily congested roading and motorway systems Port of Tauranga’s commitment to providing a seamless, efficient, cost-competitive, intermodal service MetroPort Auckland was opened in May 1999 with the signing of its first major customer - Australia New Zealand Direct Line - and operations commenced June 1999. -

A Bicultural Research Journey: the Poutama Pounamu Education Research Centre

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 467 398 RC 023 643 AUTHOR Harawira, Wai; Walker, Rangiwhakaehu; McGarvey, Te Uru; Atvars, Kathryn; Berryman, Mere; Glynn, Ted; Duffell, Troy TITLE A Bicultural Research Journey: The Poutama Pounamu Education Research Centre. PUB DATE 1999-07-00 NOTE 20p.; In: Indigenous Education around the World: Workshop Papers from the World Indigenous People's Conference: Education (Albuquerque, New Mexico, June 15-22, 1996); see RC 023 640. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Context; Cultural Relevance; *Educational Research; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Maori (People); Native Language Instruction; *Participatory Research; Peer Teaching; *Research Projects; *Special Education; Tutoring IDENTIFIERS New Zealand ABSTRACT This paper documents work undertaken by a bicultural research group at the New Zealand Special Education Service, Poutama Pounamu Education Research Centre. The research group develops and evaluates learning resources for parents and teachers of Maori students. Two projects are described. Tatari Tautoko Tauawhi (Pause Prompt Praise) assists parent and peer tutoring of reading in the Maori language. Trials of the tutoring procedures using student tutor-tutee pairs in Maori-immersion and bilingual classrooms found that both tutees and tutors improved their reading level and comprehension in both Maori and English. Training of trainers, who then instruct adult tutors, adheres closely to Maori philosophy and cultural protocols. Hei Awhina Matua is a cooperative parent and teacher program for assisting students who have behavior and learning difficulties. Both programs build on strengths of parents, teachers, and community, enabling shared responsibility for students' behavior and learning. -

Part 1: Formation, Landforms and Paleoenvironment of Matakana

Formation, landforms and palaeoenvironment of Matakana Island and implications for archaeology Formation, landforms and palaeoenvironment of Matakana Island and implications for archaeology SCIENCE & RESEARCH SERIES NO.102 Mike J. Shepherd 1 , Bruce G. McFadgen 2 , Harley D. Betts 1,Douglas G. Sutton 3 1 Department of Geography, Massey University, Private Bag 11222, Palmerston North. 2 Science and Research Division, 1 Department of Conservation, PO Box 10420, Wellington. 3 Department of Anthropology, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland. Published by Department of Conservation P.O. Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand Frontispiece: oblique photograph of Matakana Island. View to the northwest with Mount Maunganui in the foreground. Science & Research Series is a fully reviewed irregular monograph series reporting the investigations conducted by DoC staff. © April 1997, Department of Conservation ISSN 0113-3713 ISBN 0-478-018320 Cataloguing-in-Publication data Formation, landforms and palaeoenvironment of Matakana Island and implications for archaeology / Mike J. Shepherd ... {et al.}. Wellington, N.Z. : Dept. of Conservation, 1997. 1 v. ; 30 cm. (Science & Research series, 0113-3713 ; no.102.) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0478018320 1. Archaeological geology- -New Zealand- -Matakana Island. 2. Geomorphology--New Zealand- -Matakana Island. 3. Matakana Island (N.Z.) I. Shepherd, Mike.II . Series: Science & research series ; no. 102. 551.42099321 20 zbn97-028036 CONTENTS Abstract 7 1. Introduction 7 1.1 Geological setting 10 1.2 Factors controlling the growth of Matakana Barrier 10 1.2.1 Sea level 10 1.2.2 Offshore bathymetry 10 1.2.3 Wave and tidal environment 11 1.2.4 Sediment supply 11 1.2.5 Wind climate 12 1.2.6 Vegetation 13 1.3 Dating the growth of Matakana Island 13 1.3.1 Radiocarbon dating 13 1.3.2 Airfall tephra deposits and sea-rafted pumice 16 2. -

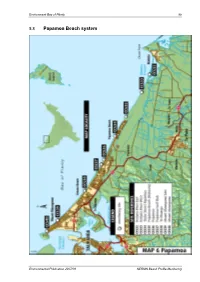

Papamoa Beach System

Environment Bay of Plenty 99 5.8 Papamoa Beach system Environmental Publication 2007/08 NERMN Beach Profile Monitoring 100 Environment Bay of Plenty 5.8.1 Kaituna River East (CCS 32) Discussion This site is located on the Maketu Spit (2.3km to the west of the Maketu Estuary and 1.1km to the east of the Kaituna Cut). The Spit is a 3.45km-long sand beach bordering a 75 to 150m-wide free form Holocene sand spit that has grown from northwest to southeast to partially enclose Maketu Estuary (Gibb, 1994). The 1978 photograph shows an accreting frontal dune with Spinifex occupying the frontal dune and runners colonising the leading face. The 2006 photograph show a similar pattern to that exhibited in 1978. Site 31, previously located to the east was lost in 1978 when the Maketu Spit was breached. The profile history shows a seaward movement of the frontal dune, accompanying this seaward movement is a marked positive vertical translation. The MHWS record shows a maximum vertical fluctuation of 17m. The offshore profiles show the presence of a dynamic bar system. Convergence occurs at -7m. The trend analysis shows a state tending towards accretion. The long-term trend (1943- 1994) of dynamic equilibrium with short-term shoreline fluctuations of 10 to 20m increasing to 20 to 30m near the Kaituna River mouth and 50 to 70m near the inlet to Maketu Estuary (Gibb,1994). NERMN Beach Profile Monitoring Environmental Publication 2007/08 Environment Bay of Plenty 101 CCS 32 - Kaituna River East Seasonal Profile Distribution 15 State: Accretion? 10 5 Location: NZMG 2812197E 6377739N 0 Period of record: 1990 – 2006 Number of Profiles Summer Autumn Winter Spring No.