UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Services Report 2009-2010

Community Services Report 2009-2010 ach year, the GRAMMY Foundation® gathers the stories of the past 12 months in our Community Services Report. For this report, we are combining the activities Einto a two-year report covering 2009 and 2010. What you’ll discover in these stories are highlights that mark some of our accomplishments and recount the inspiring moments that affirm our mission and invigorate our programs throughout the years. Since 2007, we’ve chosen to tell our stories of the past fiscal year’s achievements in an online version of our report — to both conserve resources and to enliven the account with interactive features. We hope you enjoy what you learn about the GRAMMY Foundation and welcome your feedback. MISSION Taylor Swift and Miley Cyrus and their signed guitar that was sold at a The GRAMMY Foundation was established GRAMMY® Charity Online Auctions. by The Recording Academy® to cultivate the understanding, appreciation, and advancement of the contribution of recorded music to American culture — from the artistic and technical legends of the past to the still unimagined musical breakthroughs of future generations of music professionals. OUR EDUCATION PROGRAMS Under the banner of GRAMMY in the Schools®, the GRAMMY Foundation produces and supports music education programs for high school students across the country throughout the year. The GRAMMY Foundation’s GRAMMY in the Schools website provides applications and information for GRAMMY in the Schools programs, in addition to student content. GRAMMY® CAREER DAY GRAMMY Career Day is held on university campuses and other learning environments across the country. It provides students with insight into careers in music through daylong conferences offering workshops with artists and industry professionals. -

Pops Prevails

Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 93-99 (Spring 2012) Pops Prevails Edward Berger What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years. By Ricky Riccardi. New York: Pantheon, 2011. 369 pp. $28.95. Louis Armstrong’s later work is a far more controversial subject than one would expect, given his universal recognition as jazz’s seminal creator and, at one time, arguably the world’s most recognizable figure. But it is precisely his success in these two disparate and, to many, incompatible roles that led some critics to ignore his later artistic achievements and to bemoan what many viewed as his abandonment of his genius in pursuit of popular acceptance. Add to that the uneasiness engendered in some circles by Armstrong’s complex stage persona, and the controversy becomes more understandable. Ricky Riccardi makes abundantly clear in this new and valuable work that, although Armstrong may have devoted his entire life to entertaining his audience, it did not preclude serious artistic achievement at all stages of his career. Most writers, Riccardi included, use the transition from Armstrong’s leadership of his big band to the formation of the All Stars in 1947 as the demarcation between early and late Armstrong. Since Armstrong recorded from 1923 to 1971, his “late” period spanned some 24 years—exactly half of his entire recording career. Moreover, some critics felt that Armstrong’s contributions as a creative improviser ended even earlier, essentially dismissing much of his output after the Hot Fives and Hot Sevens. It is interesting to note how our concept of age has changed over the decades. -

By Anders Griffen Trumpeter Randy Brecker Is Well Known for Working in Montana

INTERVIEw of so many great musicians. TNYCJR: Then you moved to New York and there was so much work it seems like a fairy tale. RB: I came to New York in the late ‘60s and caught the RANDY tail-end of the classic studio days. So I was really in the right place at the right time. Marvin Stamm, Joe Shepley and Burt Collins used me as a sub for some studio dates and I got involved in the classic studio when everybody was there at the same time, wearing suits and ties, you know? Eventually rock and R&B started to kind of encroach into the studio system so T (CONTINUED ON PAGE 42) T O BRECKER B B A N H O J by anders griffen Trumpeter Randy Brecker is well known for working in Montana. Behind the scenes, they were on all these pop various genres and with such artists as Stevie Wonder, and R&B records that came out on Cameo-Parkway, Parliament-Funkadelic, Frank Zappa, Lou Reed, Bruce like Chubby Checker. You know George Young, who Springsteen, Dire Straits, Blue Öyster Cult, Blood, Sweat I got to know really well on the New York studio scene. & Tears, Horace Silver, Art Blakey, Billy Cobham, Larry He was popular on the scene as a virtuoso saxophonist. Coryell, Jaco Pastorius and Charles Mingus. He worked a lot He actually appeared on Ed Sullivan, you can see it on with his brother, tenor saxophonist Michael Brecker, and his website. So, all these things became an early formed The Brecker Brothers band. -

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Special Operations Executive - Wikipedia

12/23/2018 Special Operations Executive - Wikipedia Special Operations Executive The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a British World War II Special Operations Executive organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton, from the amalgamation of three existing Active 22 July 1940 – 15 secret organisations. Its purpose was to conduct espionage, sabotage and January 1946 reconnaissance in occupied Europe (and later, also in occupied Southeast Asia) Country United against the Axis powers, and to aid local resistance movements. Kingdom Allegiance Allies One of the organisations from which SOE was created was also involved in the formation of the Auxiliary Units, a top secret "stay-behind" resistance Role Espionage; organisation, which would have been activated in the event of a German irregular warfare invasion of Britain. (especially sabotage and Few people were aware of SOE's existence. Those who were part of it or liaised raiding operations); with it are sometimes referred to as the "Baker Street Irregulars", after the special location of its London headquarters. It was also known as "Churchill's Secret reconnaissance. Army" or the "Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare". Its various branches, and Size Approximately sometimes the organisation as a whole, were concealed for security purposes 13,000 behind names such as the "Joint Technical Board" or the "Inter-Service Nickname(s) The Baker Street Research Bureau", or fictitious branches of the Air Ministry, Admiralty or War Irregulars Office. Churchill's Secret SOE operated in all territories occupied or attacked by the Axis forces, except Army where demarcation lines were agreed with Britain's principal Allies (the United Ministry of States and the Soviet Union). -

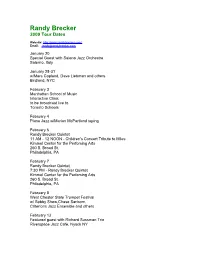

2009 Tour Dates

Randy Brecker 2009 Tour Dates Website: http://www.randybrecker.com/ Email: [email protected] January 20 Special Guest with Saleno Jazz Orchestra Salerno, Italy January 28-31 w/Marc Copland, Dave Liebman and others Birdland, NYC February 3 Manhattan School of Music Interactive Clinic to be broadcast live to Toronto Schools February 4 Piano Jazz w/Marian McPartland taping February 6 Randy Brecker Quintet 11 AM - 12 NOON - Children's Concert Tribute to Miles Kimmel Center for the Perfoming Arts 260 S. Broad St. Philadelphia, PA February 7 Randy Brecker Quintet 7:30 PM - Randy Brecker Quintet Kimmel Center for the Perfoming Arts 260 S. Broad St. Philadelphia, PA February 8 West Chester State Trumpet Festival w/ Bobby Shew,Chase Sanborn, Criterions Jazz Ensemble and others February 13 Featured guest with Richard Sussman Trio Riverspace Jazz Cafe, Nyack NY February 15 Special guest w/Dave Liebman Group Baltimore, Maryland February 20 - 21 Special guest w/James Moody Quartet Burmuda Jazz Festival March 1-2 Northeastern State Universitry Concert/Clinic Tahlequah, Oklahoma March 6-7 Concert/Clinic for Frank Foster and Break the Glass Foundation Sandler Perf. Arts Center Virginia Beach, VA March 17-25 Dates TBA European Tour w/Lynne Arriale quartet feat: Randy Brecker, Geo. Mraz A. Pinciotti March 27-28 Temple University Concert/Clinic Temple,Texas March 30 Scholarship Concert with James Moody BB King's NYC, NY April 1-2 SUNY Purchase Concert/Clinic with Jazz Ensemble directed by Todd Coolman April 4 Berks Jazz Festival w/Metro Special Edition: Chuck Loeb, Dave Weckl, Mitch Forman and others April 11 w/ Lynne Arriale Jazz Quartet Ft. -

Income and Upporting a Foxcroft Ft Annuity

Volume XXIV No. II Fall/Winter 2002 You can... Boost your Income and Cut your Taxes while Supporting Foxcroft Academy with a Foxcroft Academy Charitable Gift Annuity oxcroft Academy began offering charitable gift annuities to alumni and friends Calculations for a $10,000 of the Academy in July of 1997. Since then, alumni like Muriel Philpot Watson Single Life Annuity* F’25 and Priscilla Berberian ‘48 have made gifts ranging from $8,000 to $130,000 in gift annuity contracts. A Foxcroft Academy annuity is a wonderful opportunity ($5,000 minimum investment) to receive a generous fixed income for life, cut taxes, and help students at Foxcroft Rate of Annual Tax-Free T a x a b l e Academy as well. To date, the Academy has received over $370,000 in gifts which Charitable have been given through a gift annuity. Age Return Payment Portion Portion Deduction A Foxcroft Academy Gift Annuity provides you with a generous income for life. 55 6.0 $600 $255 $ 3 4 5 The payment rate on gift annuities is established by the American Council on $2,735 Gift Annuities. 60 6.4 $640 $294 $ 3 5 6 ! $2,916 65 6.7 $670 $334 $ 3 3 6 I am interested in receiving, at no obligation, calculations showing the $3,346 income and tax benefits of a Foxcroft Academy gift annuity. Please base the calculations on a potential agreement in the amount of $ * The Academy also offers two life annuities. Charitable deductions vary month to month based upon federal interest rate formulas. Please First Life (Date of Birth): Month Day Year: consult your attorney or tax advisor for professional counsel. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

ART FARMER NEA Jazz Master (1999)

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. ART FARMER NEA Jazz Master (1999) Interviewee: Art Farmer (August 21, 1928 – October 4, 1999) Interviewer: Dr. Anthony Brown Dates: June 29-30, 1995 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 96 pp. Brown: Today is June 29, 1995. This is the Jazz Oral History Program interview for the Smithsonian Institution with Art Farmer in one of his homes, at least his New York based apartment, conducted by Anthony Brown. Mr. Farmer, if I can call you Art, would you please state your full name? Farmer: My full name is Arthur Stewart Farmer. Brown: And your date and place of birth? Farmer: The date of birth is August 21, 1928, and I was born in a town called Council Bluffs, Iowa. Brown: What is that near? Farmer: It across the Mississippi River from Omaha. It’s like a suburb of Omaha. Brown: Do you know the circumstances that brought your family there? Farmer: No idea. In fact, when my brother and I were four years old, we moved Arizona. Brown: Could you talk about Addison please? Farmer: Addison, yes well, we were twin brothers. I was born one hour in front of him, and he was larger than me, a bit. And we were very close. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 1 Brown: So, you were fraternal twins? As opposed to identical twins? Farmer: Yes. Right. -

Acoustic Sounds Catalog Update

WINTER 2013 You spoke … We listened For the last year, many of you have asked us numerous times for high-resolution audio downloads using Direct Stream Digital (DSD). Well, after countless hours of research and development, we’re thrilled to announce our new high-resolution service www.superhirez.com. Acoustic Sounds’ new music download service debuts with a selection of mainstream audiophile music using the most advanced audio technology available…DSD. It’s the same digital technology used to produce SACDs and to our ears, it most closely replicates the analog experience. They’re audio files for audiophiles. Of course, we’ll also offer audio downloads in other high-resolution PCM formats. We all like to listen to music. But when Acoustic Sounds’ customers speak, we really listen. Call The Professionals contact our experts for equipment and software guidance RECOMMENDED EQUIPMENT RECOMMENDED SOFTWARE Windows & Mac Mac Only Chord Electronics Limited Mytek Chordette QuteHD Stereo 192-DSD-DAC Preamp Version Ultra-High Res DAC Mac Only Windows Only Teac Playback Designs UD-501 PCM & DSD USB DAC Music Playback System MPS-5 superhirez.com | acousticsounds.com | 800.716.3553 ACOUSTIC SOUNDS FEATURED STORIES 02 Super HiRez: The Story More big news! 04 Supre HiRez: Featured Digital Audio Thanks to such support from so many great customers, we’ve been able to use this space in our cata- 08 RCA Living Stereo from logs to regularly announce exciting developments. We’re growing – in size and scope – all possible Analogue Productions because of your business. I told you not too long ago about our move from 6,000 square feet to 18,000 10 A Tribute To Clark Williams square feet.