The Established Church and the Tithe War Disturbances in Clonmany 1832 – 1838

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLASS NEWS - Clonmany National School Newsletter

CLASS NEWS - Clonmany National School Newsletter June 2015 Principal Mr. W. Doherty Volume 3 , Issue 3 Vice-Principal Mrs. K. Casey Principal’s News have achieved better results in What a busy end of year we all have Literacy while also maintaining our had! Thank you all for your help, high standards in Numeracy. I hope support and kindness this year Thank we can continue the trend of you to the Board of Management, the maintaining such high standards in Parents Association, all the staff of the years to come. school, the children and to all the parents for your generosity and support We are due to lose Ms. Faulkner for throughout the year. We have had a this coming year. She is moving on to very busy and successful period since Scoil Eoghain, Moville next year and this time last year. our loss is certainly their gain – good luck Áine for the future! Áine is also Our Sacrament classes have successfully getting married this summer so we received their holy communion and in all wish her well on her big day! Contents th the case of 6 class they have successfully received the Holy Spirit in Principal’s News 1 Finally, may I take this opportunity being confirmed. Both occasions were to wish you all a very happy, safe and Sacrament Classes 1 joyous and very uplifting and occasions enjoyable summer, I look forward to that we as the school community should L.A.S.C.O. 2 seeing you all back safe and well in celebrate. September. Museuem Visitor 2 Good luck to all of our 6th Class pupils Trip to Derry 2 as they leave to start at their new William Chicks Online 2 school. -

Inishowen Heritage Trail

HERITAGE TRAIL EXPLORE INISHOWEN Inishowen is exceptional in terms of the outstanding beauty of its geography and in the way that the traces of its history survive to this day, conveying an evocative picture of a vibrant past. We invite you to take this fascinating historical tour of Inishowen which will lead you on a journey through its historical past. Immerse yourself in fascinating cultural and heritage sites some of which date back to early settlements, including ancient forts, castle’s, stone circles and high crosses to name but a few. Make this trail your starting point as you begin your exploration of the rich historical tapestry of the Inishowen peninsula. However, there are still hundreds of additional heritage sites left for you to discover. For further reading and background information: Ancient Monuments of Inishowen, North Donegal; Séan Beattie. Inishowen, A Journey Through Its Past Revisited; Neil Mc Grory. www.inishowenheritage.ie www.curiousireland. ie Images supplied by: Adam Porter, Liam Rainey, Denise Henry, Brendan Diver, Ronan O’Doherty, Mark Willett, Donal Kearney. Please note that some of the monuments listed are on private land, fortunately the majority of land owners do not object to visitors. However please respect their property and follow the Country Code. For queries contact Explore Inishowen, Inishowen Tourist Office +353 (0)74 93 63451 / Email: [email protected] As you explore Inishowen’s spectacular Heritage Trail, you’ll discover one of Ireland’s most beautiful scenic regions. Take in the stunning coastline; try your hand at an exhilarating outdoor pursuit such as horse riding, kayaking or surfing. -

Transatlantic Connections 2 Confer - That He Made, and the Major Global and Transatlantic Projects He Is Currently Ence, 2015

GETTING TO BUNDORAN Located at Donegal’s most southerly point, Bundoran is the first stop as you enter the county from Sligo and Leitrim on the main N15 Sligo to Donegal Road. By Car By Coach Bundoran can be reached by the following routes: Bus Eireann’s Route 30 provides regular coach TRANSATLANTIC From Dublin via Cavan, Enniskillen N3 service from Dublin City and Dublin Airport From Dublin via Sligo N4 - N15 to Donegal. Get off the bus at Ballyshannon From Galway via Sligo N17 - N15 Station in County Donegal. Complimentary CONNECTIONS 2 From Belfast via Enniskillen M1 - A4 - A46 transfer from Ballyshannon to Bundoran; advanced booking necessary A Drew University Conference in Ireland buseireann.com SPECIAL THANKS Our sincere gratitude to the Institute of Study Abroad Ireland for its cooperation and partnership with Drew January 1 5–18, 2015 University. Many thanks also to Michael O’Heanaigh at Donegal County Council, Shane Smyth at Discover Bundoran, Martina Bromley and Joan Crawford at Failte Ireland, Gary McMurray for kind use of Bundoran, Donegal, Ireland cover photograph, Marc Geagan from North West Regional College, Tadhg Mac Phaidin and staff at Club Na Muinteori, Maura Logue, Marion Rose McFadden, Travis Feezell from University of the Ozarks, Tara Hoffman and Melvin Harmon at AFS USA, Kevin Lowery, Elizabeth Feshenfeld, Rebeccah Newman, Macken - zie Suess, and Lynne DeLade, all who made invaluable contributions to the organization of the conference. KEYNOTE SPEAKERS DON MULLAN “From Journey to Justice” Stories of Tragedy and Triumph from Bloody Sunday to the WWI Christmas Truces Thursday, 15 January • 8:30 p.m. -

Donegal Primary Care Teams Clerical Support

Donegal Primary Care Teams Clerical Support Office Network PCT Name Telephone Mobile email Notes East Finn Valley Samantha Davis 087 9314203 [email protected] East Lagan Marie Conwell 074 91 41935 086 0221665 [email protected] East Lifford / Castlefin Marie Conwell 074 91 41935 086 0221665 [email protected] Inishowen Buncrana Mary Glackin 074 936 1500 [email protected] Inishowen Carndonagh / Clonmany Christina Donaghy 074 937 4206 [email protected] Fax: 074 9374907 Inishowen Moville Christina Donaghy 074 937 4206 [email protected] Fax: 074 9374907 Letterkenny / North Letterkenny Ballyraine Noelle Glackin 074 919 7172 [email protected] Letterkenny / North Letterkenny Railway House Noelle Glackin 074 919 7172 [email protected] Letterkenny / North Letterkenny Scally Place Margaret Martin 074 919 7100 [email protected] Letterkenny / North Milford / Fanad Samantha Davis 087 9314203 [email protected] North West Bunbeg / Derrybeg Contact G. McGeady, Facilitator North West Dungloe Elaine Oglesby 074 95 21044 [email protected] North West Falcarragh / Dunfanaghy Contact G. McGeady, Facilitator Temporary meeting organisation South Ardara / Glenties by Agnes Lawless, Ballyshannon South Ballyshannon / Bundoran Agnes Lawless 071 983 4000 [email protected] South Donegal Town Marion Gallagher 074 974 0692 [email protected] Temporary meeting organisation South Killybegs by Agnes Lawless, Ballyshannon PCTAdminTypeContactsV1.2_30July2013.xls Donegal Primary Care Team Facilitators Network Area PCT Facilitator Address Email Phone Mobile Fax South Donegal Ballyshannon/Bundoran Ms Sandra Sheerin Iona Office Block [email protected] 071 983 4000 087 9682067 071 9834009 Killybegs/Glencolmkille Upper Main Street Ardara/Glenties Ballyshannon Donegal Town Areas East Donegal Finn Valley, Lagan Valley, Mr Peter Walker Social Inclusion Dept., First [email protected] 074 910 4427 087 1229603 & Lifford/Castlefin areas Floor, County Clinic, St. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

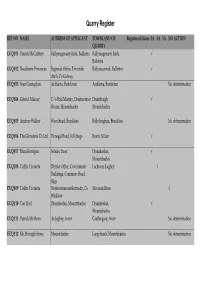

Quarry Register

Quarry Register REF NO NAME ADDRESS OF APPLICANT TOWNLAND OF Registered Status 3A 4A 5A NO ACTION QUARRY EUQY01 Patrick McCafferty Ballymagroarty Irish, Ballintra Ballymagroarty Irish, √ Ballintra EUQY02 Roadstone Provinces Regional Office, Two mile Ballynacarrick, Ballintra √ ditch, Co Galway EUQY03 Sean Granaghan Ardfarna, Bundoran Ardfarna, Bundoran No determination EUQY04 Gabriel Murray C/o Brid Murray, Drumconnor Drumbeagh, √ House, Mountcharles Mountcharles EUQY05 Andrew Walker Woodhead, Bruckless Ballyloughan, Bruckless No determination EUQY06 The Glenstone Co Ltd Donegal Road, Killybegs Bavin, Kilcar √ EUQY07 Brian Kerrigan Selacis, Inver Drumkeelan, √ Mountcharles EUQY08 Coillte Teoranta District Office, Government Lackrom, Laghey √ Buildings, Cranmore Road, Sligo EUQY09 Coillte Teoranta Newtownmountkennedy, Co Meenanellison √ Wicklow EUQY10 Con Friel Drumkeelan, Mountcharles Drumkeelan, √ Mountcharles EUQY11 Patrick Mulhern Ardaghey, Inver Castleogary, Inver No determination EUQY12 Mc Monagle Stone Mountcharles Largybrack, Mountcharles No determination Quarry Register REF NO NAME ADDRESS OF APPLICANT TOWNLAND OF Registered Status 3A 4A 5A NO ACTION QUARRY EUQY14 McMonagle Stone Mountcharles Turrishill, Mountcharles √ EUQY15 McMonagle Stone Mountcharles Alteogh, Mountcharles √ EUQY17 McMonagle Stone Mountcharles Glencoagh, Mountcharles √ EUQY18 McMonagle Stone Mountch arles Turrishill, Mountcharles √ EUQY19 Reginald Adair Bruckless Tullycullion, Bruckless √ EUQY21 Readymix (ROI) Ltd 5/23 East Wall Road, Dublin 3 Laghey √ EUQY22 -

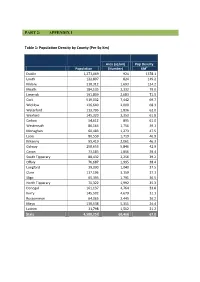

APPENDIX I Table 1: Population Density by County (Per Sq

PART 2: APPENDIX I Table 1: Population Density by County (Per Sq Km) Area (sq km) Pop Density Population (Number) KM2 Dublin 1,273,069 924 1378.1 Louth 122,897 824 149.2 Kildare 210,312 1,693 124.2 Meath 184,135 2,332 79.0 Limerick 191,809 2,683 71.5 Cork 519,032 7,442 69.7 Wicklow 136,640 2,000 68.3 Waterford 113,795 1,836 62.0 Wexford 145,320 2,353 61.8 Carlow 54,612 895 61.0 Westmeath 86,164 1,756 49.1 Monaghan 60,483 1,273 47.5 Laois 80,559 1,719 46.9 Kilkenny 95,419 2,061 46.3 Galway 250,653 5,846 42.9 Cavan 73,183 1,856 39.4 South Tipperary 88,432 2,256 39.2 Offaly 76,687 1,995 38.4 Longford 39,000 1,040 37.5 Clare 117,196 3,159 37.1 Sligo 65,393 1,791 36.5 North Tipperary 70,322 1,992 35.3 Donegal 161,137 4,764 33.8 Kerry 145,502 4,679 31.1 Roscommon 64,065 2,445 26.2 Mayo 130,638 5,351 24.4 Leitrim 31,798 1,502 21.2 State 4,588,252 68,466 67.0 Table 2: Private households in permanent housing units in each Local Authority area, classified by motor car availability. Four or At least One Two Three more one No % of motor motor motor motor motor motor HHlds All hhlds car cars cars cars car car No Car Dublin City 207,847 85,069 36,255 5,781 1,442 128,547 79,300 38.2% Limerick City 22,300 9,806 4,445 701 166 15,118 7,182 32.2% Cork City 47,110 19,391 10,085 2,095 580 32,151 14,959 31.8% Waterford City 18,199 8,352 4,394 640 167 13,553 4,646 25.5% Galway City 27,697 12,262 7,233 1,295 337 21,127 6,570 23.7% Louth 43,897 18,314 13,875 2,331 752 35,272 8,625 19.6% Longford 14,410 6,288 4,548 789 261 11,886 2,524 17.5% Sligo 24,428 9,760 -

Planning for Inclusion in County Donegal a Mapping Toolkit 2009

DONEGAL COUNTY DEVELOPMENT BOARDS Planning For Inclusion In County Donegal A Mapping Toolkit 2009 Donegal County Development Board Bord Forbartha Chontae Dhún na nGall FOREWORD CHAIRMAN OF Donegal COUNTY Development Board Following a comprehensive review of Donegal County Development Board’s ‘An Straitéis’ in 2009, it was agreed that the work of the Board would be concentrated on six key priority areas, one of which is on ‘Access to Services’. In this regard the goal of the Board is ‘to ensure best access to services for the community of Donegal’. As Chairperson of Donegal County Development Board, I am confident that the work contained in both of these documents will go a long way towards achieving an equitable distribution of services across the county in terms of informing the development of local and national plans as well as policy documents’ in both the Statistical and Mapping Documents. I would like to take this opportunity to thank all persons involved in the development of these toolkits including the agencies and officers who actively participated in Donegal County Development Board’s Social Inclusion Measures Group, Donegal County Council’s Social Inclusion Forum, Donegal County Councils Social Inclusion Unit and finally the Research and Policy Unit who undertook this work. There is an enormous challenge ahead for all of us in 2010, in ensuring that services are delivered in a manner that will address the needs of everyone in our community, especially the key vulnerable groups outlined in this document. I would urge all of the agencies, with a social inclusion remit in the county, to take cognisance of these findings with the end goal of creating a more socially inclusive society in Donegal in the future. -

O'dochartaigh Clann Association Ár Ndúthcas

NEWSLETTER #56 O’Dochartaigh Clann JUNE 2010 Association Ár nDúthcas Inside This Issue Reunion Time 2 The “Inishowen 100” 4 The “Gap of Mamore” 6 Golfer’s Paradise 8 O’Dochartaigh Castles 10 Dohertys in the News 11 From the Editor 14 The Fort, Greencastle 15 Rules of the Road 16 INCH CASTLE: An O’Dochartaigh Stronghold on Inch Island Grianan of Aileach 18 Photograph taken in 2008 by Charles Daugherty (used by permission) While Digging for Treasure, try www.odochartaigh.org Have you been digging around for you to benefit from them. order for your convenience. We in our new O’Dochartaigh 2010 will add more and more of these, website www.odochartaigh.org? 1) The area of “Genealogy & so keep checking back. Your DNA Project” is for posting infor- family can also be posted, in like What a great tool it is becoming mation and questions from those manner, if you contact Cameron for all of us! It has great poten- of you who already have had DNA Dougherty (see page 3). tial to really throw your geneal- analysis done, or those of you ogy research into high gear. who are thinking about it. This is 3) The “Genealogy Sharing by a sure way to stay in the middle Surname Spelling” provides an If everyone were to join and of all of our announcements and area for those of you with simi- participate in our website’s ge- discoveries as technology moves larly spelt last-name to find oth- nealogy discussions and post- along in this area. ers researching your family or ings, in a few short months we who have information on your would quickly have built an 2) The “Genealogy Sharing by family. -

Weekly Lists

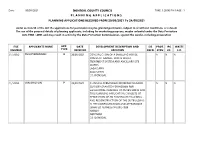

Date: 30/09/2021 DONEGAL COUNTY COUNCIL TIME: 5:20:00 PM PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 20/09/2021 To 24/09/2021 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER TYPE RECEIVED LOCATION RECD. STRU LIC. LIC. 21/51852 PHILIP BRENNAN O 20/09/2021 CONSTRUCTION OF A DWELLING HOUSE, N N N DOMESTIC GARAGE, WASTE WATER TREATMENT SYSTEM AND ANCILLARY SITE WORKS LAGACURRY BALLYLIFFIN CO. DONEGAL 21/51853 IAIN SHOVLIN P 20/09/2021 PLANNING PERMISSION REFERENCE NUMBER N N N 20/51039 GRANTED PERMISSION FOR ELEVATIONAL CHANGES TO OUTBUILDING AND THIS PLANNING APPLICATION CONSISTS OF DEMOLITION OF AN EXISTING OUTBUILDING AND RECONSTRUCTION OF THE OUTBUILDING IN THE CONFIGURATUON AND APPEARANCE GRANTED PERMISSION 20/51039 NARAN PORTNOO CO. DONEGAL Date: 30/09/2021 DONEGAL COUNTY COUNCIL TIME: 5:20:00 PM PAGE : 2 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 20/09/2021 To 24/09/2021 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. -

E 4¼A2 4¼A5 4¼A5 4¼A5 4¼A2 4¼A4

Inishtrahull Sound Malin Head #7 #\Ballyhillin e# 0 20 km 0 10 miles Glengad Head Pollan Ù# Culdaff Beach Tullagh Bay #\ Fanad Bay Malin #\ Dunmore Head #\ Head Dunaff #\ Ballyliffin Culdaff Tremore Bay ATLANTIC Head Dunaff #\Clonmany Kinnagoe Bay #10 Tory Island ls #\ Carndonagh OCEAN Lenan il Inishowen Head H #\ Head is Gleneely #\ rr Shrove U Slieve Rosguill Snaght Horn #\ \# #\ (615m) Glentogher Greencastle Tory Head Sheep Peninsula Portsalon Haven Bay Downings #\ Dunree R #\ Sound #\ Rosnakill Inishowen Moville Dunfanaghy #\ #\ Peninsula Tramore #3 #\Marblehill#\ #æ Knockalla Bloody #\ Carrigart a #\ Ù# Fort Redcastle Foreland Beach Port-na- n #÷Ards Forest R a Magheraroarty Blagh Park Kerrykeel iv er C r Brinlack#\ #\ #\ #\ Quigley's #\ Fanad Buncrana #\ Falcarragh Point Lough #\ Peninsula Tievealehid #\ Foyle Creeslough (431m) Gortahork R Muckish Rathmullan R #\ #\ Fahan Mountain #\ Milford City of Gola #\ (670m) Inch Derrybeg Errigal Island Burnfoot #\ Muff Derry Limavady Mountain #\ #\ Airport #\ Bunbeg #\ Gweedore (752m) Inch Bridge Culmore #\ Glenveagh R Ramelton #\ #\ End Bay #– Donegal Lough #2 Castle #\ Rosses #– Nacung #\ Burt 4¼A2 Airport Crolly#\ Kilmacrennan Bay #\ #\ Glenveagh Dunlewy #÷ 4¼N56 Arranmore Annagry National Island Poisoned #5 Park #] Derry #\ Kincasslagh Glen #\ Leabgarrow #\ R Lough 4¼N13 Green Burtonport Slieve Gartan #\ Church Hill LONDONDERRY Island Snaght #\ Letterkenny Boylagh #\ (683m) oyle Dungiven Dungloe F #\ Bay r 4¼E16-6 #\ e Derryveagh Newmills v i Crohy Mountains R 4¼N56 4¼A5 Head #\ Doochary -

Community & Voluntary Directory

DONEGAL COUNTY DEVELOPMENT BOARDS COMMUNITY & VOLUNTARY DIRECTORY BY GEOGRAPHICAL REMIT AUGUST 2011 Project supported by PEACE II Programme managed for the Special EU Programmes Body by Donegal County Council TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Donegal Electoral Area 2. Glenties Electoral Area 3. Inishowen Electoral Area 4. Letterkenny Electoral Area 5. Stranorlar Electoral Area Group Details By Geographical Remit Address Townland Phone Mobile Fax Email Donegal E.A. Ballintra Ballyshannon Ballintra & Laghey The Methodist Hall, Ballintra, BALLINTRA (074) 9721827 Senior Citizens Donegal P.O, Co. Donegal (GRAHAMSTOWN Welfare Committee ROAD) Aim : The Care of the Aged by providing - meals, home help, laundry service, visitation, Summer Outing & Christmas Party Drumholme c/o Mary Barron, Secretary, DRUMHOME (087) 2708745 Womens Group Ballymagroarty, Ballintra, Donegal P.O, Co. Donegal Aim : To provide an active social space for women of all ages & backgrounds Ballintra Donegal Ballintra/Laghey St. Brigid's Community LISMINTAN or (074) 9734986 (074) 9734581 paddymblproject@eircom. Development Co Centre, Ballintra, Donegal BALLYRUDDELLY net Ltd P.O, Co. Donegal Aim : The main aims of the Committee are to sustain & develop the Youth Project work for sports, cultural, educational & community development. To develop educational needs & ability to cope with life. Support for leaders, volunteers, the young & vulnerable young within the Community. Address Townland Phone Mobile Fax Email Drumholme Ballintra, Donegal P.O, Co. LISMINTAN or (074) 9723212 (087) 7531608 Community Donegal BALLYRUDDELLY Centre - Ballintra Community Centre Aim : To run a play group& to support play leader Ballyshannon Rural Donegal Mountain c/o Leo Murray, Cashel, CASHEL (071) 9859986 (087) 1330200 [email protected] Rescue Team Rossnowlagh, Donegal P.O, Co.