Christian J. Ebner193 the BONN POWERS – STILL NECESSARY?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three German Women

Three German Women Three German Women: Personal Histories from the Twentieth Century By Erika Esau Three German Women: Personal Histories from the Twentieth Century By Erika Esau This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Erika Esau All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5697-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5697-3 In Memory of Thomas Elsaesser (1943-2019) Film historian, filmmaker, cultural historian, and too late a friend. He guided this project with his enthusiasm and generosity. He was, for me, "The path through the mirror" TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix Acknowledgments .................................................................................... xiii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ................................................................................................. 9 “You Must Look at the Whole Thing, Not Just Part”: Anna von Spitzmüller (1903-2001) Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

The High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina

February 2021 KAS Office in Bosnia and Herzegovina ''Future as a duty'' – the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina Sven Petke, Suljo Ćorsulić A new High Representative will assume office in Bosnia and Herzegovina over the coming months. Valentin Inzko, an Austrian, has been holding this position since 2009. He made repeated efforts to maintain a diplomatic and fair relationship with the key political actors in Bosnia and Herzegovina. An important pre-requisite for the work of a High Representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina includes vast political experience and support by the international community. An important step for the second pre-requisite has been made with the inauguration of the US President Joe Biden: It is expected that the United States of America and the European Union will again closely coordinate their political engagement in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the neighbouring countries. Office of the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina (OHR) The citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina have lived in peace for more than 25 years. Bosnia and Herzegovina consists of two entities, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska. Bosnia and Herzegovina gained independence following an independence referendum in 1992 after the disintegration of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Bosnian Croats, Bosnian Serbs and Bosniaks were the belligerent parties in the ensuing war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. After a four-year war with over 100,000 dead, hundreds of thousands of wounded and millions of refugees, the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement was facilitated by the international community. The Peace Agreement ended the war and guaranteed the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina. -

President-Designate of the Nairobi Summit on a Mine-Free World

PRESIDENT-DESIGNATE OF THE NAIROBI SUMMIT ON A MINE-FREE WORLD WOLFGANG PETRITSCH In September 2003, Ambassador Wolfgang Petritsch, Austria’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations in Geneva, was elected President-Designate of the Convention’s First Review Conference. This event is being referred to as the 2004 Nairobi Summit on a Mine Free World, given the location of the event and the fact that it will mark the midway point between the Convention’s entry-into-force and the first deadlines for States to have cleared mined areas. In this role, Petritsch is charged with leading the substantive preparations for the Nairobi Summit, including the development of a concrete action plan to complete the job of eliminating anti- personnel mines. Prior to his appointment as Austria’s Permanent Representative in Geneva, Petritsch served between August 1999 and May 2002 as the International Community’s High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina. In this role, Petritsch was the final authority on civilian implementation of the 1995 Dayton Peace Agreement. While living in Bosnia and Herzegovina – one of the most mine-infested countries in the world – Petritsch witnessed first-hand the humanitarian impact of anti-personnel mines. Petritsch’s experience in the former Yugoslavia stretches back to 1997 when he was appointed Austrian Ambassador to the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. From October 1998 to July 1999 he served as the European Union’s Special Envoy for Kosovo and in February and March of 1999 as the European Union’s Chief Negotiator at the Kosovo peace talks in Rambouillet and Paris. Petritsch’s diplomatic career also has seen him serve in Paris and New York. -

Austrian Federalism in Comparative Perspective

CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 24 Bischof, Karlhofer (Eds.), Williamson (Guest Ed.) • 1914: Aus tria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I War of World the Origins, and First Year tria-Hungary, Austrian Federalism in Comparative Perspective Günter Bischof AustrianFerdinand Federalism Karlhofer (Eds.) in Comparative Perspective Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) UNO UNO PRESS innsbruck university press UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Austrian Federalism in ŽŵƉĂƌĂƟǀĞWĞƌƐƉĞĐƟǀĞ Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 24 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2015 by University of New Orleans Press All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70148, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Book design by Allison Reu and Alex Dimeff Cover photo © Parlamentsdirektion Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608011124 ISBN: 9783902936691 UNO PRESS Publication of this volume has been made possible through generous grants from the the Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration, and Foreign Affairs in Vienna through the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York, as well as the Federal Ministry of Economics, Science, and Research through the Austrian Academic Exchange Service (ÖAAD). The Austrian Marshall Plan Anniversary Foundation in Vienna has been very generous in supporting Center Austria: The Austrian Marshall Plan Center for European Studies at the University of New Orleans and its publications series. -

Congress of Vienna Program Brochure

We express our deep appreciation to the following sponsors: Carnegie Corporation of New York Isabella Ponta and Werner Ebm Ford Foundation City of Vienna Cultural Department Elbrun and Peter Kimmelman Family Foundation HOST COMMITTEE Chair, Marifé Hernández Co-Chairs, Gustav Ortner & Tassilo Metternich-Sandor Dr. & Mrs. Wolfgang Aulitzky Mrs. Isabella Ponta & Mr. Werner Ebm Mrs. Dorothea von Oswald-Flanigan Mrs. Elisabeth Gürtler Mr. & Mrs. Andreas Grossbauer Mr. & Mrs. Clemens Hellsberg Dr. Agnes Husslein The Honorable Andreas Mailath-Pokorny Mr. & Mrs. Manfred Matzka Mrs. Clarissa Metternich-Sandor Mr. Dominique Meyer DDr. & Mrs. Oliver Rathkolb Mrs. Isabelle Metternich-Sandor Ambassador & Mrs. Ferdinand Trauttmansdorff Mrs. Sunnyi Melles-Wittgenstein CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 2 Presented by the The CHUMIR FOUNDATION FOR ETHICS IN LEADERSHIP is a non-profit foundation that seeks to foster policies and actions by individuals, organizations and governments that best contribute to a fair, productive and harmonious society. The Foundation works to facilitate open-minded, informed and respectful dialogue among a broad and engaged public and its leaders to arrive at outcomes for a better community. www.chumirethicsfoundation.ca CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 2 CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 3 CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 4 UNDER THE DISTINGUISHED PATRONAGE OF H.E. Heinz Fischer, President of the Republic of Austria HONORARY CO-CHAIRS H.E. Josef Ostermayer Minister of Culture, Media and Constitution H.E. Sebastian Kurz Minister of Foreign Affairs and Integration CHAIR Joel Bell Chairman, Chumir Foundation for Ethics in Leadership CONGRESS SECRETARY Manfred Matzka Director General, Chancellery of Austria CHAIRMAN INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY COUNCIL Oliver Rathkolb HOST Chancellery of the Republic of Austria CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 4 CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 5 CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 6 It is a great honor for Austria and a special pleasure for me that we can host the Congress of Vienna 2015 in the Austrian Federal Chancellery. -

Regional Economic Development in Europe and the United States

Regional Economic Development in Europe and the United States: The European Union and the American South Compared A Workshop Organized and Sponsored by the Austrian Marshall Plan Foundation and CenterAustria of the University of New Orleans New Orleans, Oct. 20-21, 2013 PROGRAM Sunday, October 20, 2013 Arrival in New Orleans 7 p.m. Welcome Out of Town Guests Monday, October 21, 2013 9 a.m. EARL K. LONG LIBRARY, Room 407 Welcome and Opening Remarks Günter Bischof CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Eugen Stark Austrian Marshall Plan Foundation Wolfgang Petritsch Harvard University James Earl Payne Provost, University of New Orleans - 1 - PROGRAM 9:15 a.m. – 10:45 a.m. EARL K. LONG LIBRARY, Room 407 Regional Economic Development Strategies in the European Union and the South Chair: James Earl Payne Provost, University of New Orleans The Regional Policy of the European Union: Aims, Methods and Reform Ronald Hall Directorate General for Regional & Urban Policy European Commission, Brussels Regional Economic Development in the South since World War II James Cobb University of Georgia - 2 - PROGRAM 11:00 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. EARL K. LONG LIBRARY, Room 407 The Economics of Regional Development Chair: Walter L. Lane University of New Orleans Theories of Regional Development and Implications for the Housing Market Elisabeth Springler University of Applied Sciences bfi Vienna Economic Development Incentives Trap and Accountability Cynthia L. Rogers & Steve Ellis University of Oklahoma 12:30 p.m. – 2:00 p.m. Lunch, Chancellor’s Dining Room, UC - 3 - PROGRAM 2:00 p.m. – 3:30 p.m. EARL K. -

Introduction

Introduction “As I have said time and again, my job is to get rid of my job. I am quite clear that the OHR is now into the terminal phase of its mandate”, said then High Representative for the international community in BIH Paddy Ashdown in his speech in front of the Venice Commission1 in October 2004. For over eight years now the international community has been discussing the downscale of its presence in Bosnia and Herzegovina2, which since the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement in 1995 has been run as a virtual protectorate. But not much has changed since Ashdown’s speech. Although the country has gone forward in all fields and the security situation has improved drastically since 1995, with the number of NATO peacekeeping forces decreasing from 60,000 to only 1,6003 and with BIH currently a temporary member of the UN Security Council, no arrangements have been made to grant more sovereignty to local politics. And due to recent negative developments in politics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the prospect of getting rid of the ‘informal trusteeship’ now seems more distant than it was at the time of Ashdown’s speech. The OHR, acronym for Office of the High Representative, is the international body responsible for overseeing the implementation of the civilian aspects of the treaty which ended the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is governed by a council of 55 countries and international organizations charged with overseeing Bosnia’s reconstruction, formally organized into an umbrella organization called the Peace Implementation Council (PIC). It is the PIC who 1The European Commission for Democracy through Law, better known as the Venice Commission, is the Council of Europe's advisory body on constitutional matters. -

Bad Memories. Sites, Symbols and Narrations of Wars in the Balkans

BAD MEMORIES Sites, symbols and narrations of the wars in the Balkans Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso www.osservatoriobalcani.org BAD MEMORIES Sites, symbols and narrations of the wars in the Balkans Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Contributions to the conference “Bad Memories” held in Rovereto on 9th November 2007 Provincia autonoma di Trento BAD MEMORIES Sites, symbols and narrations of the wars in the Balkans © Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso, 2008 EDITING Chiara Sighele and Francesca Vanoni TRANSLATIONS Risto Karajkov and Francesca Martinelli PROOFREADING Harold Wayne Otto GRAPHIC DESIGN Roberta Bertoldi COVER PAGE PHOTO Andrea Rossini LAYOUT AND PRINT Publistampa Arti grafiche, October 2008 Recycled paper Cyclus made of 100% macerated paper, whitened without using chlorine Table of content Introduction Bad Memories. Sites, symbols and narrations of the wars in the Balkans Luisa Chiodi 9 Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso A think-tank on South-East Europe, Turkey and the Caucasus 15 WORLD WAR II. POLICIES OF MEMORY IN YUGOSLAVIA Monuments’ Biographies. Sketches from the former Yugoslavia Heike Karge 19 Between Memory Politics and Mourning. Remembering World War II in Yugoslavia Wolfgang Höpken 27 Private Memories, Official Celebrations Nicole Janigro 33 «Dobar dan. Kako ste? Ja sam dobro, hvala. Jeste li dobro putovali?» What language is this? Nenad Šebek 39 THE WARS OF THE 1990s. MEMORIES IN SHORT CIRCUIT Commemorating Srebrenica Ger Duijzings 45 Ascertaining Facts for Combating Ideological Manipulation Vesna Teršelicˇ 53 The Importance of Every Victim Mirsad Tokacˇa 59 Serbia Without Monuments Natasˇ a Kandic´ 63 THE 21st CENTURY. MEMORY AND OBLIVION IN EUROPE What Future for the Past? Wolfgang Petritsch 71 A European Memory for the Balkans? Paolo Bergamaschi 77 Extinction of Historical Memory and Nazi Resurgence. -

Interview: Wolfgang Petritsch, the High Representative for Bih:”Good Faith for Peaceful Balkans”

Interview: Wolfgang Petritsch, the High Representative for BiH:”Good Faith for Peaceful Balkans” Old Administration in Belgrade thought that I was pro-Albanian. The reason why I had to leave Belgrade on the day when the NATO air strikes began was the fact that the Belgrade administration was spreading lies on television claiming that I promised Kosovo would become independent, which of course was not true. Austrian diplomat, until May this year in the position of the High Representative for BiH, Wolfgang Petritsch has gained great experience in the territory of former Yugoslavia. As an Ambassador or Envoy he has worked in Serbia and BiH. He was praised and criticized for almost everything he did. Currently, while he is coming to the end of his mandate in BiH, he is drawing attention to himself by insisting on constitutional changes, which, according to many, would determine the success of his stay in BiH. “My time hasn’t yet run out. I still do have time in my mandate. When you take the Dayton Peace Agreement into consideration, I think that the issue of return of refugees is the essence of the DPA. This year, the figures of returns are very impressive, almost 40% higher than the previous year. The year of 2000 was called a year of breakthrough in return of refugees by the Human Rights Watch”, assesses Petritsch the results of his work in an interview for Reporter. Reporter: However, we are not talking about figures only. How are things with real life in BiH? Petritsch: The more important thing than the figures relating to returns is a real return to their homes by those who have that right and that is a recognized fact in the whole of BiH now. -

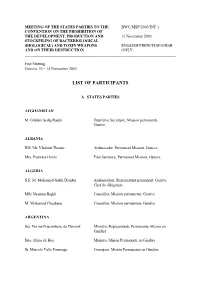

List of Participants

MEETING OF THE STATES PARTIES TO THE BWC/MSP/2003/INF.1 CONVENTION ON THE PROHIBITION OF THE DEVELOPMENT, PRODUCTION AND 13 November 2003 STOCKPILING OF BACTERIOLOGICAL (BIOLOGICAL) AND TOXIN WEAPONS ENGLISH/FRENCH/SPANISH AND ON THEIR DESTRUCTION ONLY ___________________________________________________________________________ First Meeting Geneva, 10 – 14 November 2003 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS A. STATES PARTIES AFGHANISTAN M. Ghulam Sediq Rasuli Deuxième Secrétaire, Mission permanente Genève ALBANIA H.E. Mr. Vladimir Thanati Ambassador, Permanent Mission, Geneva Mrs. Pranvera Goxhi First Secretary, Permanent Mission, Geneva ALGERIA S.E. M. Mohamed-Salah Dembri Ambassadeur, Représentant permanent, Genève Chef de délégation Mlle Nassima Baghli Conseiller, Mission permanente, Genève M. Mohamed Chaabane Conseiller, Mission permanente, Genève ARGENTINA Sra. Norma Nascimbene de Dumont Ministro, Representante Permanente Alterno en Ginebra Srta. Alicia de Hoz Ministro, Misión Permanente en Ginebra Sr. Marcelo Valle Fonrouge Consejero, Misión Permanente en Ginebra BWC/MSP/2003/INF.1 Page 2 AUSTRALIA H.E. Mr. Michael Smith Ambassador to the Conference on Disarmament and Permanent Representative, Geneva Head of Delegation Dr. Geoffrey Shaw Counsellor and Deputy Representative to the Conference on Disarmament, Geneva Mr. Peter Truswell Third Secretary Delegation to the Conference on Disarmament Geneva Dr. Robert Mathews Principal Research Scientist Defence Scientific and Technology Organisation Department of Defence, Melbourne AUSTRIA H.E. Mr. Wolfgang Petritsch Ambassador, Permanent Representative, Geneva Head of Delegation Ms. Dorothea Auer Minister plenipotentiary Federal Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Vienna Deputy Head of Delegation Mr. Alexander Kmentt Counsellor, Permanent Mission, Geneva Deputy Head of Delegation Mr. Peter Grabner Brigadier General, Military Adviser Permanent Mission, Geneva BAHRAIN H.E. Mr. Saeed Mohamed Al-Faihani Ambassador, Permanent Representative, Geneva Mr. -

Balkan Kot Šansa / the Balkans As a Chance Friedensbildung Strukturell Verankern

„BALKAN ALS CHANCE“ Balkan kot šansa / The Balkans as a Chance Friedensbildung strukturell verankern „Erinnern“, „Versöhnen“, „Zukunft gestalten“ – diese Worte fallen im Gedenkjahr 2014 oft. Jedes Mal, wenn wir sie aussprechen, berüh- ren wir Dimensionen eines Ausmaßes, das sich sprachlich sehr schwer fassen lässt: Die Tragö- dien, die Menschen in den vergangenen hun- dert Jahren erlebt haben, die Eskalation von Ana Blatnik Gewalt, die Versuche, Brücken über schein- Präsidentin des Bundesrates © Parlamentsdirektion/WILKE bar Unüberbrückbares zu bauen und die viel- schichtigen Herausforderungen, die vor uns liegen. Welche schwierigen Prozesse einer Annäherung vorausgehen, nachdem Lebenswelten zerstört worden sind, hat die Geschichte im- mer wieder gezeigt. Der ehemalige Hohe Repräsentant der EU für Bos- nien und Herzegowina, Wolfgang Petritsch, bezeichnete diese Vorgän- ge einmal als „eine Art Arbeit am Steinbruch der Schicksale“. Er bezog sich dabei auf die Kärntner Ortstafelfrage, doch meiner Ansicht nach lässt sich dieses aussagekräftige Bild auf den Umgang mit viel weitrei- chenderen Konflikten in und außerhalb Europas anwenden. Eine „Arbeit am Steinbruch der Schicksale“ ist auch das Bemühen um eine gemeinsame Gedenk- und Erinnerungskultur. Zugleich aber ist diese gemeinsame Kultur Voraussetzung dafür, dass wieder etwas Neues entstehen kann. Wer Gemeinsames über Trennendes stellt, beschreitet oft einen Weg der leisen Schritte, für die man keinen lau- ten Beifall erntet. Doch in Initiativen für ein friedvolles, konstruktives Impressum: Miteinander liegt die Chance, die es zu ergreifen gilt. Um den „Balkan Herausgeberin, Herstellerin und Medieninhaberin: Parlamentsdirektion als Chance“ ging es in einer Konferenz am 21. Oktober 2014, von der Adresse: Dr. Karl Renner-Ring 3, 1017 Wien, Österreich vielleicht der eine oder andere positive Impuls für ein Miteinander in Redaktion: Susanne Bachmann, Barbara Blümel Vielfalt ausgeht. -

DIE FURCHE-Herausgeber Heinz Nußbaumer Über In- Den Einzelnen

| Im Porträt | 9 ❙ Meine Meinung ❙ ❙ Die Hungerzeichen der Zeit S. 10 Oliver Tanzer über die Debatte zum Agrartreibstoff E10 und verfehlte Maßnahmen der Klimapolitik. „ Es zeichnet Wolfgang ❙ Presse international ❙ Petritsch aus, dass ❙ Terror am Horn von Afrika S. 10 Die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung über den Einfl uss er für sich nicht die radikaler Islamisten in den Staaten Nordafrikas. leichtesten Wege aus- ❙ Auf ein Wort ❙ ❙ „Asma“ ist überall (II) S. 10 sucht. Er übersieht nie DIE FURCHE-Herausgeber Heinz Nußbaumer über In- den Einzelnen. teressen und – fehlende – Moral im Syrien-Konfl ikt. ❙ Interview ❙ “ ❙ Endlich Staatsbürger S. 12 Der Sudanese Amir al-Amin über seinen hindernisrei- Bub EIN chen Weg zur österreichischen Staatsbürgerschaft. eine Freundschaft mit Wolf- Leben irgendetwas unwiederbringlich ge- gang Petritsch hat zweifel- ändert hatte.“ los einen ungewöhnlichen Wolfgang Petritsch ist zunächst zwei- Beginn. In beinahe mär- sprachiger Kärntner Volksschullehrer ge- chenhaft entfernter Zeit worden, hat dann bald in Wien zu studie- Mwar ich Schulsprecher des Bundesgymnasi- ren begonnen und sein Geschichtestudium ums für Sloweninnen und Slowenen in Kla- mit einer zweibändigen, 800 Seiten umfas- genfurt/Celovec und hatte die Vorstellung, senden Dissertation über die slowenischen Bundeskanzler Bruno Kreisky zu einer Dis- Studenten in Wien seit dem Jahr 1848 abge- kussion über die Kärntner Slowenen im Ver- schlossen. Danach war er noch Fulbright- gleich zu den Südtirolern einzuladen. Die Stipendiat an der University of Southern Idee war so provokant gedacht, wie Gymna- California in Los Angeles, bevor es in das Ka- siasten, die ihre ersten Gedichte schon ver- binett Kreisky ging, wo er lange Jahre Pres- öffentlicht hatten, eben gestrickt sind.