'One Book, One Pen, One Child, and One Teacher Can Change the World!'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebration and Rescue: Mass Media Portrayals of Malala Yousafzai As Muslim Woman Activist

Celebration and Rescue: Mass Media Portrayals of Malala Yousafzai as Muslim Woman Activist A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Wajeeha Ameen Choudhary in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2016 ii iii Dedication To Allah – my life is a culmination of prayers fulfilled iv Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have possible without the love and support of my parents Shoukat and Zaheera Choudhary, my husband Ahmad Malik, and my siblings Zaheer Choudhary, Aleem Choudhary, and Sumera Ahmad – all of whom weathered the many highs and lows of the thesis process. They are my shoulder to lean on and the first to share in the accomplishments they helped me achieve. My dissertation committee: Dr. Brent Luvaas and Dr. Ernest Hakanen for their continued support and feedback; Dr. Evelyn Alsultany for her direction and enthusiasm from many miles away; and Dr. Alison Novak for her encouragement and friendship. Finally, my advisor and committee chair Dr. Rachel R. Reynolds whose unfailing guidance and faith in my ability shaped me into the scholar I am today. v Table of Contents ABSTRACT ……………………..........................................................................................................vii 1. INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW...………….……………………………………1 1.1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………...1 1.1.1 Brief Profile of Malala Yousafzai ……….………...…………...………………………………...4 1.2 Literature Review ………………………………………………………………………………….4 1.2.1 Visuality, Reading Visual -

The Politics of Representation in the Climate Movement

The Politics of Representation in the Climate Movement Article by Alast Najafi July 17, 2020 For decades, the tireless work of activists around the world has advanced the climate agenda, raising public awareness and political ambition. Yet today, one Swedish activist’s fame is next to none. Alast Najafi examines how the “Greta effect” is symptomatic of structural racial bias which determines whose voices are heard loudest. Mainstreaming an intersectional approach in the climate movement and environmental policymaking is essential to challenge the exclusion of people of colour and its damaging consequences on communities across the globe. The story of Greta Thunberg is one of superlatives and surprises. In the first year after the schoolgirl with the signature blond braids emerged on the public radar, her fame rose to stratospheric heights. Known as the “Greta effect”, her steadfast activism has galvanised millions across the globe to take part in climate demonstrations demanding that governments do their part in stopping climate change. Since she started her school strike back in August 2018, Greta Thunberg has inspired numerous and extensive tributes. She has been called an idol and the icon the planet desperately needs. The Church of Sweden even went so far as to playfully name her the successor of Jesus Christ. These days, Greta Thunberg is being invited into the corridors of power, such as the United Nations and the World Economic Forum in Davos where global leaders and chief executives of international corporations listen to her important message. Toward the end of 2019, her media exposure culminated in a nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize and an extensively covered sail across the Atlantic with the aim of attending climate conferences in New York and Chile. -

Our Education IT’S ABOUT US

! Our Education IT’S ABOUT US Aim: To learn about the role of education in affecting change ! Objectives: Young people will... • Learn about the work of Malala Yousafzai, an inspiring education activist. • Learn about the broad benefits of education. • Understand the role for education in driving progress and societal transformation. • Understand the vital importance of ensuring girls are educated. ! Background Resources and Links: ! • The Value of Education • UNICEF & MDG 2 (Education) • Key Messages and Data on Girls’ and Women’s Education and Literacy You! will need: 10 - 15 Worksheets with SDG headings. Workshops by Vivienne Parry © UNICEF Ireland. View: • Malala Speech to UN - Malala Yousafzai is a Pakistani school pupil and education activist from Pakistan. She is known for her education and girls’ rights activism. In early 2009, at the age of 11, Malala began blogging for the BBC in Urdu under 18m the pen name ‘Gul Makai’. She detailed her life under Taliban rule and her objections to the Taliban prohibition on girls’ education. On 9 October 2012, Malala, 14 years old, was shot in the head and neck in an assassination attempt by Taliban gunmen while returning home on a school bus. She survived the assassination attempt but the Taliban has reiterated its intent to kill Malala and her father. In this video, Malala - now 16 - speaks to the United Nations at her first public speaking engagement since her attack. OR • Malala Yousafzai on The Daily Show - In this exclusive interview with Jon Stewart following the release of her book, "I Am Malala", she remembers the Taliban's rise to power in her Pakistani hometown and discusses her efforts to campaign for equal access to education for girls. -

Angela Davis Fadumo Dayib

ANGELA DAVIS Angela Davis was born in 1944 in Alabama, USA, in her youth she experienced racial prejudice and discrimination. Angela links much of her political activism to her time with the Girl Scouts of the USA in the 1950s. As a Girl Scout, she marched and protested racial segregation in Birmingham. From 1969, Angela began public speaking. She expressed that she was against; the Vietnam War, racism, sexism, and the prison system, and expressed that she supported gay rights and other social justice movements. Angela opposed the 1995 Million Man March, saying that by excluding women from the event, they promoted sexism. She said that the organisers appeared to prefer that women take subordinate roles in society. Together with Kimberlé Crenshaw and others, she formed the African American Agenda 2000, an alliance of Black feminists. WAGGGS • WORLD THINKING DAY 2021 • FADUMO DAYIB Fadumo Dayib is known for being the first woman to run for president in Somalia. After migrating with her younger siblings to Finland, to escape civil war in Somalia she worked tirelessly so that she could return to her country and help her people regain freedom and peace. After learning how to read at the age of 14 she has since earned one bachelor’s degree, three master’s degrees and went on to pursue a PhD. She worked with the United Nations to set up hospitals throughout Somalia and decided to run for president even though it was extremely dangerous. Even though she did not win, she has not given up on helping people all over Somalia access a safe standard of living and when asked why she says “I see my myself as a servant to my people”. -

The Ideology of Women Empowerment in Malala Yousafzai's Speeches

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI THE IDEOLOGY OF WOMEN EMPOWERMENT IN MALALA YOUSAFZAI’S SPEECHES: A CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS A THESIS Presented to the Graduate Program in English Language Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Magister Humaniora ( M.Hum.) in English Language Studies by Mentari Putri Pramanenda Sinaga 166332004 THE GRADUATE PROGRAM OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2018 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI iii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY This is to certify that all the ideas, phrases, and sentences, unless otherwise stated, are the ideas, phrases, sentences of the thesis writer. The writer understands the full consequences including degree cancellation if she took somebody else's idea, phrase, or sentence without a proper reference. Yogyakarta, 3 April 2018 Mentari Putri Pramanenda Sinaga iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMISI Yang bertandatangan dibawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma: Nama : Mentari Putri Pramanenda Sinaga Nomor Mahasiswa : 166332004 Demi perkembangan ilmu pengetahuan, saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul: THE IDEOLOGY OF WOMEN EMPOWERMENT IN MALALA YOUSAFZAI’S SPEECHES: A CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS beserta perangkat yang diperlukan. Dengan demikian, saya memberikan hak kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma untuk menyimpan, mengalihkan dalam media lain, mengelolanyadalam bentuk pangkalan data, mendistribusikannya secara terbatas, dan mempublikasikannya di internet atau media lain untuk kepentingan akademis tanpa perlu meminta ijin dari saya maupun meberikan royalti kepada saya selama tetap mencantumkan nama saya sebagai penulis. Demikian pernyataan ini saya buat dengan sebenarnya. -

Inspired by Gandhi: Mahatma Gandhi's Influence on Significant

112 anna katalin aklan Inspired by Gandhi: Mahatma Gandhi’s Influence on Significant Leaders of Nonviolence 113 115 #2 / 2020 history in flux pp. 115 - 124 anna katalin aklan eötvös loránd university, department of indian studies, budapest UDC <070.11:316.485Gandhi, M.>:327 https://doi.org/10.32728/flux.2020.2.6 Review article Inspired by Gandhi: Mahatma Gandhi’s Influence on Significant Leaders of Nonviolence The leader of the Indian independence movement, Mahatma Gandhi, left an invaluable legacy: he proved to the world that it was possible to achieve political aims without the use of violence. He was the first political activist to develop strategies of nonviolent mass resistance based on a solid philosophical and uniquely religious foundation. Since Gandhi’s death in 1948, in many parts of the 115 world, this legacy has been received and continued by others facing oppression, inequality, or a lack of human rights. This article is a tribute to five of the most faithful followers of Gandhi who have acknowledged his inspiration for their political activities and in choosing nonviolence as a political method and way of life: Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Martin Luther King, Louis Massignon, the Dalai Lama, and Malala Yousafzai. This article describes their formative leadership and their significance and impact on regional and global politics and history. KEYWORDS: Gandhi, nonviolence, Ghaffar Khan, Martin Luther King, Massignon, Dalai Lama, Malala Yousafzai, Gandhi’s legacy, human rights, passive resistance anna katalin aklan: Inspired by Gandhi: Mahatma Gandhi’s Influence on Significant Leaders of Nonviolence One of the most revolutionary and influential figures of twentieth- century history is undoubtedly Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the Father of the Indian Nation. -

Pray the Devil Back to Hell: Film Teaching Guide

Pray the Devil Back to Hell: Film Teaching Guide Mr. Frank Swoboda Boston Public Schools Prepared for Primary Source Summer Institute: Modern African History: Colonialism, Independence, and Legacies (2015) Frank Swoboda, Boston Public Schools Abstract: Pray the Devil Back to Hell is a documentary that tells the story of Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace, a women’s peace movement in Liberia that eventually ended the Second Liberian Civil War (1999-2003) fought between the army controlled by then- President Charles Taylor and the rebelling forces loyal to a variety of warlords. The women’s movement also contributed to the reconstruction of Liberia, including a transition to a functioning multiparty democracy headed by Africa’s first democratically elected woman president. The film relies on archive footage of Liberia during the civil war as well as interviews with major participants in the peace process reflecting on their work and achievements. The film shows how “ordinary” Liberian women from all walks of life united in their common hope that the war would end, used a variety of protest and civil disobedience strategies to call local and global attention to the suffering the war was causing, and successfully pressured government leaders and warlords to negotiate a sustainable and just end to the war. The film is noteworthy in that it does not shy away from the violence and horrors of the war (in fact, several scenes are rather graphic, showing or referencing child warfare, torture, rape and sexual violence, and other disturbing topics). At the same time, the film is engaging (even humorous in places), is full of inspirational moments, and carries a message of hope and resilience. -

Year 8 Ethics Unit 1: Inspirational Leaders

YEAR 8 ETHICS UNIT 1: INSPIRATIONAL LEADERS Overview Key Words This unit considers inspirational leaders and their work – Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa, the Dalai Lama and Aung San Inspiration/Inspirati Suu Kyi and others. This unit is aimed at developing pupil knowledge and understanding of the issues these people were involved with and onal for pupils to reflect on the role played by them. Spiritual Religious Good and inspirational leaders Religious Beliefs and leaders Influential Nobel What qualities do you think a good or Does religious belief affect action? Buddhism/Buddhist Would these people be leaders without their religious beliefs? inspirational leader needs to have? Archbishop What sort of a person should they be? The 14th Dalai Lama Desmond Tutu Aung San Suu Kyi Belief/Believe Gandhi Characteristics of Inspiring Leaders Non-violence They express unerring positivity Ahimsa They can find the bright side of any issue They are grateful to their team Co-operation They have a crystal clear vision for the future Segregation They listen Prejudice They communicate with clarity Discrimination They are trustworthy Non-violence They are passionate Boycott Nicky Cruz Oscar Romero They have faith in themselves and in others Compassion Fellowship Teresa Mahatma Gandhi Calcutta Poverty Who was Mahatma Gandhi? Malala Yousafzai What did Mahatma Gandhi do? Taliban Was Gandhi an inspirational leader? The top three are also Nobel Prize laureates, having each Education received the Nobel Prize for Peace for the work they did in Universal Mohandas K. Gandhi 91869 – 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti- campaigning for peace in their respective countries. -

Counter-Terrorism Reference Curriculum

COUNTER-TERRORISM REFERENCE CURRICULUM CTRC Academic Project Leads & Editors Dr. Sajjan M. Gohel, International Security Director Asia Pacific Foundation Visiting Teacher, London School of Economics & Political Science [email protected] & [email protected] Dr. Peter Forster, Associate Professor Penn State University [email protected] PfPC Reference Curriculum Lead Editors: Dr. David C. Emelifeonwu Senior Staff Officer, Educational Engagements Canadian Defence Academy Associate Professor Royal Military College of Canada Department of National Defence [email protected] Dr. Gary Rauchfuss Director, Records Management Training Program National Archives and Records Administration [email protected] Layout Coordinator / Distribution: Gabriella Lurwig-Gendarme NATO International Staff [email protected] Graphics & Printing — ISBN XXXX 2010-19 NATO COUNTER-TERRORISM REFERENCE CURRICULUM Published May 2020 2 FOREWORD “With guns you can kill terrorists, with education you can kill terrorism.” — Malala Yousafzai, Pakistani activist for female education and Nobel Prize laureate NATO’s counter-terrorism efforts have been at the forefront of three consecutive NATO Summits, including the recent 2019 Leaders’ Meeting in London, with the clear political imperative for the Alliance to address a persistent global threat that knows no border, nationality or religion. NATO’s determination and solidarity in fighting the evolving challenge posed by terrorism has constantly increased since the Alliance invoked its collective defence clause for the first time in response to the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 on the United States of America. NATO has gained much experience in countering terrorism from its missions and operations. However, NATO cannot defeat terrorism on its own. Fortunately, we do not stand alone. -

4Th Asia-Pacific Meeting on Education 2030 (APMED2030) 12-14 July 2018 Karin Hulshof, UNICEF Regional Director East Asia Pacific

4th Asia-Pacific Meeting on Education 2030 (APMED2030) 12-14 July 2018 Karin Hulshof, UNICEF Regional Director East Asia Pacific Date: Thursday, 12 July 2018 Time: 08:45 – 09:30 Location: Landmark Hotel Bangkok • Ms. Watanaporn Ra-Ngubtook, Deputy Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Education, Thailand; • Mr. Yosuke Kobayashi, Deputy Secretary General, Japanese National Commission for UNESCO; • Ms. Stefania Giannini, Assistant Director General for Education, UNESCO and Mr. Shigeru Aoyagi, Director, UNESCO Bangkok; • Excellencies from participating countries and organizations, On behalf of my colleague, Jean Gough, Director of UNICEF South Asia Regional Office and myself, I would like to welcome you all to the 4th Asia-Pacific Meeting on Education 2030 (APMED2030), co-organized by UNICEF and UNESCO. When Malala Yousafzai received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014 she challenged us. She said: “the world can no longer accept that basic education is enough. Leaders must seize this opportunity to guarantee a free, quality, primary and secondary education for every child. Some will say this is impractical, or too expensive, or too hard. Or maybe even impossible. But it is time the world thinks bigger.” The challenge launched by Malala was to think against the odds. This dream was formalized in SDG 4, and in particular in Targets 4.3 and 4.4, which aim to support adolescents and youth to have better lives through improved education and training 1 opportunities at technical secondary and higher education levels. That is why I would like to congratulate all of us today for choosing these SDG Targets as the focus of this year’s meeting. -

Malala Yousafzai

Malala Yousafzai Malala Yousafzai by ReadWorks Photo Credit: DFID - UK Department for International Development (Malala Yousafzai: Education for girls), CC BY 2.0 Photograph of Malala Yousafzai Malala Yousafzai was born on July 12, 1997, in Mingora, Pakistan. As a young child, Malala was exposed to the importance of education. Her father was in charge of running a local learning institution and instilled in Malala the value of attending school. Everything changed for Malala and her family when the Taliban began to have more authority in the Swat Valley region around 2007. The Taliban, a violent fundamental Islamist group, prohibited females from participating in many activities, including attending school. The Taliban were so committed to banning female access to education that they destroyed around 400 schools within two years of their control. But Malala would not be deterred from her passion for learning. Not only did she continue to attend school, but she also spoke publicly about her dissent. On a Pakistani televised ReadWorks.org · © 2017 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. Malala Yousafzai program, Malala was brave enough to express her disbelief; "How dare the Taliban take away my basic right to education?" Malala boldly proclaimed. Under the pseudonym 'Gul Makai,' she also began to blog about what it was like as a female under the Taliban's oppressive rule. Life became so dangerous for Malala and her family that they had to flee their home as a temporary safety measure. When they returned, Malala and her father started to become more vocal in opposition to the Taliban's sexist rules. -

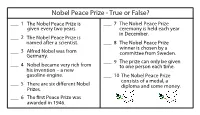

Nobel Peace Prize - True Or False?

Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___ 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___ 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. ceremony is held each year in December. ___ 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___ 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a ___ 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. ___ 9 T he prize can only be given ___ 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. his invention – a new gasoline engine. ___ 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. Prizes. ___ 6 The rst Peace Prize was awarded in 1946 . Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___F 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___T 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. Every year ceremony is held each year in December. ___T 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___F 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a Norway ___F 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. Sweden ___F 9 T he prize can only be given ___F 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. Two or his invention – a new more gasoline engine. He got rich from ___T 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize dynamite T consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money.