Ventilation in Energy Efficient UK Homes: a User Experience of Innovative Technologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humidity-Sensitive, Demand-Controlled Ventilation Applied to Multiunit Residential Building—Performance and Energy Consumption in Dfb Continental Climate

energies Article Humidity-Sensitive, Demand-Controlled Ventilation Applied to Multiunit Residential Building—Performance and Energy Consumption in Dfb Continental Climate Jerzy Sowa * and Maciej Mijakowski Faculty of Building Services, Hydro and Environmental Engineering, Warsaw University of Technology, Nowowiejska 20, 00-653 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-22-234-7428 Received: 16 November 2020; Accepted: 8 December 2020; Published: 17 December 2020 Abstract: Humidity-sensitive, demand-controlled ventilation systems have been in use for many years in regions with oceanic climates. Some attempts have been made to apply this technology in Poland, which has a continental climate. This article evaluates the performance and energy consumption of such a system when applied in an eight-floor, multiunit, residential building, i.e., the virtual reference building described by the National Energy Conservation Agency (NAPE), Poland. Simulations using the computer program CONTAM were performed for the whole heating season based upon the climate in Warsaw. Besides passive stack ventilation, that served as a reference, two ventilation systems were studied: one standard and one “hybrid” system with additional roof fans. This study confirmed that the application of humidity-sensitive, demand-controlled ventilation in multiunit residential buildings in a continental climate (Dfb) led to significant energy savings (up to 11.64 kWh/m2 of primary energy). However, the operation of the system on higher floors was found to be ineffective. Ensuring consistent operation of the system on all floors required supplementary fans. The introduction of a hybrid mode reduced carbon dioxide concentrations by approximately 32% in the units located in the upper part of the building. -

The Effect of Refurbishment and Trickle Vents on Airtightness: the Case of a 1930S Semi-Detached House

The effect of refurbishment and trickle vents on airtightness: the case of a 1930s semi-detached house. Ben Roberts*1, David Allinson1, Kevin Lomas1, and Stephen Porritt1 1 School of Civil and Building Engineering Loughborough University Loughborough, UK Presenting author *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT As UK homes are insulated and draught proofed in an attempt to reduce wintertime heating demand they become more airtight. Any reduction in infiltration could have a detrimental effect on indoor air quality. Controllable background ventilation provided by trickle vents is one method of maintaining indoor air quality. A 1930s semi-detached 3-bedroom house was refurbished with double-glazed windows, trickle vents, doors and loft insulation. 167 blower door tests were carried out pre- and post-refurbishment between January and March 2017 to understand the repeatability of the test and quantify how trickle vents affect airtightness. The refurbishment reduced air leakage by 29% from 20.8 to 14.7m3/h/m2 at 50Pa (with all windows and trickle vents closed), but still in excess of the current UK regulations for new builds (10m3/h/m2 at 50Pa). Opening trickle vents provided limited additional ventilation, only increasing air change rate by 1.8m3/h/m2 with all vents open. The test was found to be repeatable with a standard error of 0.07m3/h/m2 at 50Pa with no relationship between the test result and wind speed or direction. The results lead to two important conclusions. Firstly, after refurbishing older homes of this type, infiltration rates are still well above recommendations for adequate indoor air quality. -

03 Indoor Climate

03 Indoor Climate Introduction It is the atmosphere of a living space. It captures and displays the essence of a home. It fills the outer form with life. It creates harmony (or disharmony), which affects the entire human condition – mind, soul, and body. Figure: The hearth as the center of warmth. Healthy indoor climate due to a radiant heating system and natural building materials such as wood and clay. Photo: Dirk Dittmar, Building Biology Consulting Office IBN The selection of building materials and the type of construction influence the quality of the indoor climate, which very much defines both the quality of living in a given building as well as its biological effect. We should always keep this in mind with almost any building project, be it small or big. The following discussion not only applies to residential buildings but also to schools, hospitals, nursing homes, and especially to the large number of office spaces and workshops. Today there is so much talk about a positive work "climate" and a people-friendly work environment that the health and human factor aspects of indoor climate are often overlooked. Even in places where performance is a priority such as educational institutions and workplaces, a healthy indoor climate is just as important as organization, efficiency, and optimum indoor furnishings and technologies. In addition to the quantitative performance, an appropriate indoor climate promotes human health (low sick leave rates, reaching old age), contentment, well-being, and generally a positive work or 1 learning environment. And as has been repeatedly demonstrated, it also has a positive impact on work performance. -

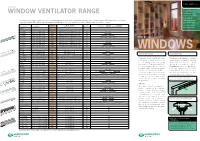

Window Ventilator Range

D A T A S H E E T W R 1 GREENWOOD REQUIREMENTS WINDOW VENTILATOR RANGE UNDER PART F: MEANS OF VENTILATION FOR WINDOW Greenwood offers a range of window ventilators for varying application requirements including through frame, glazed in and overframe. All products have been tested in MANUFACTURERS conjunction with BS EN 13141-1 Clause 4 Ventilation for Buildings at third party accredited test houses. All information is available on request. AND INSTALLERS SUppLYING NEW Equivalent Dimensions (mm) Slot Length Central Gap Length Product Code Configuration Area (mm2) (length x height x deep) Height (mm) Slot Sizes (mm) BUILD WINDOWS A Vent 3000A.12 Inner Unit & Outer Canopy 1813 Inner: 280 x 18 x 6.5 Outer: 280 x 26 x 24 12 250 4000A.12 Inner Unit & Outer Canopy 2623 Inner: 375 x 18 x 6.5 Outer: 375 x 26 x 24 12 334 6000A.12 Inner Unit & Outer Canopy 3935 Inner: 555 x 18 x 6.5 Outer: 555 x 26 x 24 12 250 15 250 8000A.12 Inner Unit & Outer Canopy 5013 Inner: 725 x 18 x 6.5 Outer: 725 x 26 x 24 12 334 15 334 NEW BUILD 3000A.16 Inner Unit & Outer Canopy 1644 Inner: 230 x 18 x 6.5 Outer: 230 x 26 x 24 16 188 4000A.16 Inner Unit & Outer Canopy 2393 Inner: 290 x 18 x 6.5 Outer: 290 x 26 x 24 16 250 6000A.16 Inner Unit & Outer Canopy 3397 Inner: 415 x 18 x 6.5 Outer: 415 x 26 x 24 16 375 8000A.16 Inner Unit & Outer Canopy 3935 Inner: 555 x 18 x 6.5 Outer: 555 x 26 x 24 16 250 15 250 D Vent WINDOWS 2000DF Inner Unit & External Grille 1396 Inner: 219 x 26.5 x 11 13 165 4000DF Inner Unit & External Grille 2770 Inner: 414 x 26.5 x 11 13 165 30 165 INDOOR -

Evaluating Ventilation Systems for Existing Homes

Evaluating Ventilation Systems for Existing Homes Robb Aldrich and Lois Arena Consortium for Advanced Residential Buildings February 2013 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, subcontractors, or affiliated partners makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. Available electronically at http://www.osti.gov/bridge Available for a processing fee to U.S. Department of Energy and its contractors, in paper, from: U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information P.O. Box 62 Oak Ridge, TN 37831-0062 phone: 865.576.8401 fax: 865.576.5728 email: mailto:[email protected] Available for sale to the public, in paper, from: U.S. Department of Commerce National Technical Information Service 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 phone: 800.553.6847 fax: 703.605.6900 email: [email protected] online ordering: http://www.ntis.gov/ordering.htm Printed on paper containing at least 50% wastepaper, including 20% postconsumer waste ii Evaluating Ventilation Systems for Existing Homes Prepared for: The National Renewable Energy Laboratory On behalf of the U.S. -

Heating and Cooling with Focus on Increased Energy Efficiency and Improved Comfort Low Exergy Systems for Heating and Cooling of Buildings

Heating and Cooling with Focus on Increased Energy Efficiency and Improved Comfort Low Exergy Systems for Heating and Cooling of Buildings Abstract: Environment problems such as global warming, which have been linked to the extended use of energy, and the negative environmental effects of energy production which they are mainly due to the use of fossil fuels. Heating, cooling and lighting appliances in buildings cause more than one third of the world’s primary energy demand. Then using renewable energy sources for heating and cooling buildings is very important for safe future energy demand .Increasing energy efficiency and improving thermal comfort can realize by using low exergy systems for heating and cooling of buildings. ‘Low exergy systems’ means systems that provide heating or cooling energy at a temperature close to room temperature. Low temperature heating systems or high temperature cooling systems can use a variety of fuels and renewable energy sources, having many benefits such as: improved thermal comfort, improved indoor air quality, reduced energy consumption and reduced draughts and dust. Active and passive systems: Passive systems defined as building envelope systems use various environment potentials as sun, wind. Active systems are consisting of various mechanical and electric components as fans, heat pumps… Energy, Exergy, and Entropy: In the theory of thermodynamics, Exergy is the maximum work that can be obtains from an energy flow or a change of a system. Exergy analysis provides us with additional information on where and when the losses occur. It helps us to see in which part of the energy chain the biggest savings can be achieve. -

Multifamily Ventilation – Best Practice?

Multifamily Ventilation – Best Practice? Dianne Griffiths April 29, 2013 Presentation Outline • Basic Objectives • Exhaust Systems • Make-up Air Systems Two Primary Ventilation Objectives 1) Providing Fresh Air - Whole-House 2) Removing Pollutants - Local Exhaust Our goal is to find the simplest solution that satisfies both objectives while minimizing cost and energy impacts. Common Solution: Align local exhaust with fresh air requirements (Ex: 25 Bath + 25 Kitchen) Exhaust-Driven Fresh Air Design • Exhaust slightly depressurizes the units • Outside air enters through leaks, cracks, or planned inlets • Widely used in the North Multifamily Ventilation Best Practice • Step 1: Understand ventilation requirements • Step 2: Select the simplest design that can achieve both air quality and energy objectives • Step 3: Build a tight building • Step 4: Pay attention to installation quality • Step 5: Check to make sure ventilation works • Step 6: Educate users Exhaust: Central and Unitized Central Exhaust Unitized Exhaust Standard Central Exhaust Practice Roof or mushroom fans Vertical shaft with horizontal take-offs Sidewall or ceiling grilles at each floor Continuous operation Mechanical Designers’ Intent • Balancing damper transferring responsibility to balancing contractor • Many grilles, many floors, relatively low flow targets, plus wind and weather on balancing day = balancing is difficult Automatic Balancing Dampers 30 CFM60 CFM 30 CFM40 CFM 30 CFM20 CFM Balance in two ways: 30 CFM30 CFM • Provide restriction in size of opening (increase static pressure) 30 CFM20 CFM • Dynamically self-adjust to changes in the system (automatic balancing) 30 CFM10 CFM Duct Leakage Roof curb? Takeoffs? Transverse (sectional) joints? Register Longitudinal (lengthwise) connections joints? can be the largest set of leaks Best Practice • Include performance specifications for duct tightness in construction documents • Call out specific details to be sealed: all joints, takeoffs, connections, registers, etc., etc. -

Humidity-Sensitive Demand-Controlled Ventilation Applied to Multi-Unit Residential Building – Performance and Energy Consumption in Dfb Continental Climate

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 16 November 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202011.0406.v1 Article Humidity-sensitive demand-controlled ventilation applied to multi-unit residential building – performance and energy consumption in Dfb continental climate Jerzy Sowa 1, *, Maciej Mijakowski 2 1 Faculty of Building Services, Hydro an Environmental Engineering, Warsaw University of Technology, Nowowiejska 20, Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Building Services, Hydro an Environmental Engineering, Warsaw University of Technology, Nowowiejska 20, Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-22-234-7428 Abstract: A humidity-sensitive demand-controlled ventilation system is known for many years. It has been developed and commonly applied in regions with an oceanic climate. Some attempts were made to introduce this solution in Poland in a much severe continental climate. The article evaluates this system's performance and energy consumption applied in an 8-floor multi-unit residential building, virtual reference building described by the National Energy Conservation Agency NAPE, Poland. The simulations using the computer program CONTAM were performed for the whole hating season for Warsaw's climate. Besides passive stack ventilation that worked as a reference, two versions of humidity-sensitive demand-controlled ventilation were checked. The difference between them lies in applying the additional roof fans that convert the system to hybrid. The study confirmed that the application of demand-controlled ventilation in multi-unit residential buildings in a continental climate with warm summer (Dfb) leads to significant energy savings. However, the efforts to ensure acceptable indoor air quality require hybrid ventilation, which reduces the energy benefits. -

Ventilation Considerations

Ventilation Considerations Modern Living In a world of increasing environmental concerns and rising energy prices the modern home has become much more energy efficient. This is generally a good thing but there can be some associated drawbacks with this new way of living. Up until the late 1960’s there was natural ventilation in many homes largely due to the absence of double glazing. This took the form of poorly fitting windows, doors and open fire places. Modern practices, designed to prevent drafts, save heat and keep energy bills low have inadvertently eliminated all natural ventilation. • Double glazing • Draught excluders • Fitted carpets (which prevent air movement up through suspended wooden floorboards) • Central heating (and the removal or blocking up of open fire places) Buildings have become, in effect, sealed from any natural flow of air. This provides better conditions for condensation build up; airborne contaminants from flooring materials, furnishings and cleaning products. The air exhaled by the occupants and any tobacco smoke can build up and can affect health adversely. Damp can arise from the many sources of water vapour in the modern house. Current building regulations require ventilation be fitted to new homes to maintain a flow of healthy fresh air through the house and prevent internal air contamination and damp. However ventilation accessories are often omitted from replacement windows because their function is not fully understood and because of the increased costs. And yet indoor air quality and effective ventilation is more important now than ever, not only for the buildings but for its occupants. The Repercussions of Air Tight Homes “Fresh Air is healthy, stale air is not. -

Lessons in Air Tightness and Air Quality from the Japanese 'Sick House'

Lessons in air tightness and air quality from the Japanese ‘sick house’ experience Andy Russell, Proctor Group Australia Towards Higher Performing Homes: The Role of Ventilation and Airtightness Wellington, New Zealand 20th March 2018 § Background to the sick house issues in Japan § Revision to the Japanese Building Standard Law in 2003 (materials & ventilation provisions) § Trickle vents – only one side of the equation § Trickle vents and 24hr mechanical ventilation in Japan § Drawing parallels with where we are today Traditional design for climate Headline news Why did sick house syndrome become such an issue? § House price bubble § 1970s and 80s saw a big increase in supply § Manufactured wood products (Plywood, MDF etc.) structural, furnishings, vinyl wall paper, carpets, flooring, mineral fibre insulation § High emissions of VOCs § Air tightness - low air change rates under 0.2 ach § Lifestyle changes § Spread of air conditioning § High renewal cycle (30 years) Japanese Ventilation Requirements § Building Standards Law previously required the supply of outdoor air to habitable rooms. § Mechanical Ventilation § Natural Ventilation § Min ratio of openings to floor area of 1:20 (5%) § Local exhaust of bathrooms and kitchens § Further new regulation introduced in 2003 to address the sick house problem § Also for buildings over 3,000m² & 8,000m² there is a performance requirement and mandatory IAQ testing every 2 months. Drivers for air tightness § Energy efficiency – effectiveness of insulation § Thermal comfort – reduce infiltration -

Passive House Informed: the Next Level of Energy Efficiency in Affordable Housing

Passive House informed: the next level of energy efficiency in affordable housing Amanda Donofrio, Mike Magee, Julie Romig Bergsund DeLaney Architecture & Planning, Eugene, Oregon ABSTRACT: In 2012, Bergsund DeLaney Architecture and Planning (BDA) designed an affordable housing community for St. Vincent DePaul Society of Lane County (SVdP) that included two six-unit buildings with identical floor plans and orientation, each constructed to a different sustainability standard: Passive House and Earth Advantage. Research groups from the University of Oregon School of Architecture (UO) conducted two studies, one that analyzed life cycle decisions made in the early design process and another that monitored and analyzed energy use post-occupancy. All of the research conducted by the UO was made available to the project team for review and use. The research has proved valuable not only to validate and support the decisions made during the design and construction of the Passive House, but also to inform future building design. This paper presents a framework to review the strategies used in the two case study buildings and determine recommendations for Passive House informed construction. KEYWORDS: passive house, affordable housing, energy efficient design, research collaboration INTRODUCTION Affordable housing programs exist to subsidize tenant rent and assist low-income individuals and families from becoming house poor, but tenants are typically responsible for the cost of their utilities. As energy costs continue to increase, energy efficient design in affordable housing has become a high priority for owners looking to pass utility saving onto tenants. Over the past decade, funding for affordable housing has required participation in green building certification programs as a way to confirm a commitment to energy efficient design. -

OTHER VENTILATION TECHNOLOGIES – How to Be Positive and How to Keep Cool POSITIVE INPUT VENTILATION We've Now Reached the Fi

OTHER VENTILATION TECHNOLOGIES – How to be positive and how to keep cool POSITIVE INPUT VENTILATION We’ve now reached the fifth article in my mini-series about ventilation – I said at the outset that it was a complex subject. In the first article, we looked at the four main systems of ventilation given in the Building Regulations’ Approved Document F, ‘Means of Ventilation’. In passing, the document says that Positive Input Ventilation (PIV) may also be acceptable. The main attraction of this system must be its simplicity. It is basically a fan in the loft which blows air from the loft to the hallway or stairwell below. This increases slightly the air pressure in the whole house, and so air in all the rooms is gradually expelled through the fabric of the building. Heat is saved as the result of taking in fresh air from the loft, rather than from outside. Air in the loft is said to be about 3ºC warmer on average, due to solar warming of the roof and the conduction of heat through the loft insulation. (This latter effect must be smaller, nowadays, because of the greater thickness of loft insulation being used.). A large filter keeps out pollen, dust, etc. PIV systems were originally developed in Britain in the 1970’s to deal with condensation problems in old houses. But they are also very relevant to new build today. A BRE Information Paper says that a PIV system may result in lower energy use than a conventional extract system. (See Further Info.) If PIV is to be used in a timber frame house, make doubly sure that the vapour control membrane of the walls is intact.