Spies Like Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nice Lawyers Finish First

Nice Lawyers Finish First Sean Carter Humorist at Law MONDAY DECEMBER 3, 2018 WEBINAR This page intentionally left blank. Nice Lawyers Finish First Webinar featuring Sean Carter Increasingly, lawyer civility and conge- • Diffuse tensions among warring clients; niality are becoming a thing of the past. • Secure accommodations from opposing Yet, it doesn’t have to be that way. Civil counsel; litigation need not lead to all-out civil Mon., December 3, 2018 war. As legal professionals, lawyers have an • Structure more mutually beneficial arrange- 11:00 am - 1:00 pm obligation to act just that way – professionally. ments with clients; In this presentation, the presenter will remind Sean Carter, Humorist at Law, has crisscrossed lawyers that zealous advocacy does not require the country delivering his Lawpsided Seminars. us to be zealots. It’s possible to be courteous, Each year, he presents more than 100 humorous NE MCLE Accreditation kind, accommodating and effective. In fact, for programs on such topics as legal ethics, stress #163921 (Distance learning) the continued well-being of the profession (and management, constitutional law, legal market- 2 CLE ethics hour the individual lawyer), it’s necessary. In particu- ing and much more. He is the author of the lar, Mr. Carter will discuss practical ways to: first-ever comedic legal treatise -- If It Does Not Fit, Must You Acquit?: Your Humorous Guide to the • Reduce the hostility in interactions with even Law. Mr. Carter graduated from Harvard Law the most difficult opposing counsel; School in 1992. www.nebar.com • Increase camaraderie among colleagues; REGISTRATION FORM: Nice Lawyers Finish First Webinar - December 3, 2018 c $130 - Regular Registration Please let us know how you heard about this CLE event: c $100 - NSBA dues-paying member c Email (eCounsel, listserv, etc.) c Social Media c Free - I paid 2018 NSBA dues and would like to claim c Nebraska Lawyer c Another NSBA CLE event my 2 free ethics credits (member benefit). -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Download Download

HOLLYWOOD'S WAR ON THE WORLD: THE NEW WORLD ORDER AS MOVIE Scott Forsyth Introduction 'Time itself has got to wait on the greatest country in the whole of God's universe. We shall be giving the word for everything: industry, trade, law, journalism, art, politics and religion, from Cape Horn clear over to Smith's Sound and beyond too, if anything worth taking hold of turns up at the North Pole. And then we shall have the leisure to take in the outlying islands and continents of the earth. We shall run the world's business whether the world likes it or not. The world can't help it - and neither can we, I guess.' Holroyd, the American industrialist in Joseph Conrad, Nostromo, 1904. 'Talk to me, General Schwartzkopf, tell me all about it.' Madonna, singing 'Diamonds are a Girl's Best Friend,' Academy Awards Show, 1991. There is chilling continuity in the culture of imperialism, just as there is in the lists of its massacres, its gross exploitations. It is there in the rhetoric of its apologists - from Manifest Destiny to Pax Britannica to the American Century and now the New World Order: global conquest and homogenisa- tion, epochal teleologies of the most 'inevitable' and determinist nature imaginable, the increasingly explicit authoritarianism of political dis- course, the tension between 'ultra-imperialism' and nationalism, both of the conquerors and the conquered. In this discussion, I would like to consider recent American films of the Reagan-Bush period which take imperialism as their narrative material - that is, America's place in the global system, its relations with diverse peoples and political forces, the kind of America and the kind of world which are at stake. -

THE BORN AGAIN IDENTITY Created by Rob Howard • David Guthrie

READ THIS SCRIPT ONLINE, BUT PLEASE DON’T PRINT OR COPY IT! THE BORN AGAIN IDENTITY Created by Rob Howard • David Guthrie © 2018 Little Big Stuff Music, LLC Running Time: 38:00 (The stage is the set of spy headquarters. It has a retro spy feel to it. A large map of Jerusalem is framed stage right. Stage left there is an easel with a large pad of paper. There is a desk toward the back with a globe on it, full of stacks of paper and folders. A science table with interesting looking beakers with colored water, and a retro looking switchboard are toward the back. Near the science table is a bird cage or perch with a few fake parrots. At the front stage left, a scribe sits at a desk with papers and a pen. Older Dee enters and approaches the desk.) (music begins to “Spies Like Us”) SCRIBE: Good morning, Dee. Or should I call you, Agent Dee? OLDER DEE: Oh, Dee is fine. Thank you. SCRIBE: Everyone loves a good spy novel. This is exciting! OLDER DEE: Writing my memoirs is not something I ever thought I’d do. Where do I begin? SCRIBE: Tell me what it was like to be a spy in Jerusalem, and I’ll start getting it down on paper. SONG: “SPIES LIKE US” (The stage comes to life as agents busy around Headquarters during the song.) verse 1 No one’s ever seen us, but you know you need us No one’s ever heard us, well maybe once Another informant, saying what’s important We do what we do for everyone chorus 1 Spies like us, we’re adventurous When it’s treacherous, we’re courageous 1 READ THIS SCRIPT ONLINE, BUT PLEASE DON’T PRINT OR COPY IT! When complications arise we’ll improvise We’re masters of disguise Spies like us, spies like us verse 2 Undercover agents, secret information Clandestine operations, it’s really fun Good versus evil, working for the people We won’t have a sequel, we’re never done chorus 2 Spies like us, we’re adventurous When it’s treacherous, we’re courageous We’re especially trained for whatever we face Every mystery we’ll explain Spies like us, spies like us (agents freeze during dialog at measure 69) SCRIBE: Let’s talk about one of your biggest cases, Dee. -

Antinuclear Politics, Atomic Culture, and Reagan Era Foreign Policy

Selling the Second Cold War: Antinuclear Cultural Activism and Reagan Era Foreign Policy A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy William M. Knoblauch March 2012 © 2012 William M. Knoblauch. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Selling the Second Cold War: Antinuclear Cultural Activism and Reagan Era Foreign Policy by WILLIAM M. KNOBLAUCH has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by __________________________________ Chester J. Pach Associate Professor of History __________________________________ Howard Dewald Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT KNOBLAUCH, WILLIAM M., Ph.D., March 2012, History Selling the Second Cold War: Antinuclear Cultural Activism and Reagan Era Foreign Policy Director of Dissertation: Chester J. Pach This dissertation examines how 1980s antinuclear activists utilized popular culture to criticize the Reagan administration’s arms buildup. The 1970s and the era of détente marked a decade-long nadir for American antinuclear activism. Ronald Reagan’s rise to the presidency in 1981 helped to usher in the “Second Cold War,” a period of reignited Cold War animosities that rekindled atomic anxiety. As the arms race escalated, antinuclear activism surged. Alongside grassroots movements, such as the nuclear freeze campaign, a unique group of antinuclear activists—including publishers, authors, directors, musicians, scientists, and celebrities—challenged Reagan’s military buildup in American mass media and popular culture. These activists included Fate of the Earth author Jonathan Schell, Day After director Nicholas Meyer, and “nuclear winter” scientific-spokesperson Carl Sagan. -

DVD List As of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret

A LIST OF THE NEWEST DVDS IS LOCATED ON THE WALL NEXT TO THE DVD SHELVES DVD list as of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret Garden, The Witches, The Neverending Story, 5 Children & It) 5 Days of War 5th Quarter, The $5 A Day 8 Mile 9 10 Minute Solution-Quick Tummy Toners 10 Minute Solution-Dance off Fat Fast 10 Minute Solution-Hot Body Boot Camp 12 Men of Christmas 12 Rounds 13 Ghosts 15 Minutes 16 Blocks 17 Again 21 21 Jumpstreet (2012) 24-Season One 25 th Anniversary Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Concerts 28 Weeks Later 30 Day Shred 30 Minutes or Less 30 Years of National Geographic Specials 40-Year-Old-Virgin, The 50/50 50 First Dates 65 Energy Blasts 13 going on 30 27 Dresses 88 Minutes 102 Minutes That Changed America 127 Hours 300 3:10 to Yuma 500 Days of Summer 9/11 Commission Report 1408 2008 Beijing Opening Ceremony 2012 2016 Obama’s America A-Team, The ABCs- Little Steps Abandoned Abandoned, The Abduction About A Boy Accepted Accidental Husband, the Across the Universe Act of Will Adaptation Adjustment Bureau, The Adventures of Sharkboy & Lavagirl in 3-D Adventures of Teddy Ruxpin-Vol 1 Adventures of TinTin, The Adventureland Aeonflux After.Life Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Murder of Roger Ackroyd Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Sad Cypress Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Hollow Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Five Little Pigs Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Lord Edgeware Dies Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Evil Under the Sun Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Murder in Mespotamia Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Death on the Nile Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Taken at -

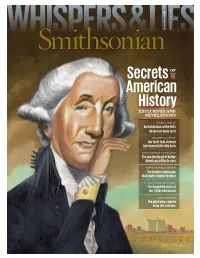

An Inside Look at the FBI's Desperate Mole Hunt EXCLUSIVES and REVELATIONS of the Theft That Steered Him Toward Little Big

5 smithsonian.com WHISPERS LIES201 November Sm it h sonian OF EXCLUSIVES AND REVELATIONS SPIES LIKE US An inside look at the FBI’s desperate mole hunt CUSTER’S HEIST The theft that steered him toward Little Big Horn RECOVERED TREASURE The greatest haul of Native American artifacts ever THE WITCHIEST WITCH The bizarre confession that ignited Salem hysteria SLAVE TRAIL OF TEARS The forgotten story of the 1,000-mile march SHOOTDOWN The pilot who came in from the cold war SMITHSONIAN.COM SECRETS OF AMERICAN HISTORY THE PHANTOM MENACE I L L U S T R A T I O N S B Y WAS A MOLE BEHIND THE JONATHAN BARTLETT S T I L L - U N E X P L A I N E D B E T R AYA L S T H E C I A SUFFERED D U R I N G ONE OF ITS MOST CATASTROPHIC YEARS? A N D I S H E ( O R S H E ) STILL OUT THERE? BY DAVID WISE SMITHSONIAN.COM SMITHSONIAN.COM Aldrich Ames’ spying (above: a London, May 17, 1985: Oleg Gordievsky note recovered from his trash) was at the pinnacle of his career. A skilled intelli- led to his arrest (above). But his gence officer, he had been promoted a few months debriefing couldn’t explain the loss of three major assets. before to rezident, or chief, of the KGB station in the British capital. Moscow seemed to have no clue he’d been secretly working for MI6, the British secret intel- ligence service, for 11 years. -

Causeway Comes up at to All the Moms City Council Tuesday

CAR-RT SORT **R003 15900001006409 THU 000000 - CAMIBEL LIBRARY '•! !•- 770 nUNLOP RD .S 5ANIUEL PL 33957 LGoforYu-GI-Oh! Page 14 Week of May 2-8, 2003 SANIBEL & CAPTIVA, FLORIDA VOLUME 30, NUMBER 19, 24 PAGES 75 CENTS LEEv COUNTY Causeway comes up at To all the moms DELINQUENT TAX By Kate Thompson NOTICES City Council Tuesday Staff writer .COMING IN THIS PAPER : ':$&Sl N EXT WEEK ?••'" &i$ Mother's Day was first celebrated in Philadelphia in 1907 at the request of Anna Jarvis who wanted to honor her deceased mother. A few years later, Jarvis In addition to publica and her friends launched a campaign to create a nation- tion in the Cape Cora al Mother's Day and in 1914, Congress passed legisla- Daily Breeze and th« tion marking the second Sunday in May as Mother's Island Reporter, the Lee Day. County Tax Collector's While the U.S. Census Bureau doesn't provide Office delinquent ta: information that would identify the number of mothers notices will be availabl living on Sanibel and Captiva, it is possible to deter- at numerous locations mine there are about 75 million mothers nationwide. throughout Lee County Some 67 percent of women between 15 and 44 in including all offices oi Kentucky are mothers — which has one of the highest the Lee County Tax birth rates in the nation. Collector, special news- There are 346 families on Sanibel living with chil- paper racks and al dren — most of them married couples. And Sanibel has offices of the Breez a much larger than typical percentage of families Corp, including North which consist of married couples — with or without Fort Myers, Cape Coral, children. -

Stolfi Surprised

The Daily Campus Serving the Storrs Community Since 1896 VoL LXXXIXNo. 60 The University of Connecticut Thursday, Dec 5, 1985 Strassle stays; Stolfi surprised By Kim Nauer what USG needs right now is a about their public image has Daily Campus Staff "low-key" president "I trust affected their ability to work With the assembly's unoffi- Art [Strassle]. He's not going as a team, he added cial support. Undergraduate to do anything wrong" she Rienks disagreed saying Student Government presi- said "He's more a player on that many members don't dent Art Strassle chose not to the team rather than dic- care how they look in77ie resign, thereby foiling the re tatorial leader," Rienks Daily Campus. "We don't election plans of former presi- added have to be conscious of our dent Jay Stolfi. Other members felt that he image if we just concentrate Strassle said that he knew had no choice but to stay on on the students," Rienks that Stolfi wanted to come after the publicity around said back at some point, but said Stolfi stating his intentions to Member Steve Protter felt he didn't know that Stolfi "resume the presidency," at that Stolff s re-election move wanted to return at last Monday night's executive was an insult to the assem- night's meeting until he read it committee meeting bly's intelligence "Everyone I in 77ie Daily Campus on "How could he, in good talked to felt it was an insult" Tuesday. conscience, resign if he Protter said. "1 laughed when I saw it, doesn't agree with whafs Member Jeff Taylow said actually," Strassle said going on," Dawn Hatzis said that he was glad there was not Strassle would not say In general, members said an election, because he did when or why he decided to that they felt that Stolfi had not want to decide whether to retain the presidency. -

Animal House

Today's weather: Our second century of Portly sunny. excellence breezy. high : nea'r60 . Vol. 112 No. 10----= Student Center, University of Delaw-.re, Newark, Del-.ware 19716 Tuesday, October 7, 1986 Christina District residents to vote today 9n tax hike Schools need .more funds plained, is divided into two by Don Gordon parts: Staff Reporter • An allocation of money to . Residents of the Christina build a $5 million elementary School District will vote· today school south of Glasgow High on a referendum which could School and to renovate the 1 John Palmer Elementary J increase taxes for local homeowners to provide more School. THE REVIEW/ Kevin McCready t • A requirement for citizens money for district schools. Mother Nature strikes again - Last Wednesday's electrical storm sends bolts of lightning Dr. Michael Walls, to help pay fo~ supplies and superintendent of the upkeep of schools. through the night. The scene above Towne Court was captured from the fourth floor of Dickinson F. Christina School District, said "We don't have enough if the referendum is passed books to go around," Walls salary." and coordinator of the referen ing the day, or even having homeowners inside district stressed. Pam Connelly (ED 87) a dum, said he expects several two sessions which would at boundaries - which include In addition, citizens' taxes student-teacher at Downes thousand more persons to vote tend school during different residential sections of Newark would help pay for higher Elementary School, said new than did in 1984. parts of the year, Walls said. - will pay an additional 10 teacher salaries. -

Summer Camp and Swim Guide 2020

Sueand Swim Lessons Cam Celebrating(1960 - 2020)60 Years 2020 EDITION REGISTRATION BEGINS MARCH 1 WWW.MONMOUTHCOUNTYPARKS.COM REGISTRATION INFORMATION FOR 2020 Children's SUMMER CAMP & SWIM LESSONS If you want to register for Monmouth County Park System Summer Camps and Swim Lessons, these are the dates to remember: SUNDAY, MARCH 1: Registration opens for Summer Camps and Swim Lessons. You can register online at www.MonmouthCountyParks.com beginning at 12:00 PM or by phone at 732-842-4000, ext. 1, from 12:00-2:00 PM. After March 1 you can register: ONLINE: 24/7 BY PHONE: Call 732-842-4000, ext. 1, Monday through Friday, 8:00 AM-4:30 PM. BY MAIL: Use the registration form on page 67 of this Parks and Programs Guide. Mail the form to: Registrations Monmouth County Park System 805 Newman Springs Road Lincroft, NJ 07738 Checks or money orders should be made payable to: Board of Recreation Commissioners IN PERSON: Visit Thompson Park Headquarters, Newman Springs Road, Lincroft, Monday through Friday, 8:00 AM-4:30 PM. You may register family members ONLY for as many camps or swim lessons as you wish. (For online registration at www.MonmouthCountyParks.com, please create an account with a separate profile for each family member.) TABLE OF CONTENTS Park System Spotlight 2-3 Odyssey Adventures 34-37 Park Amenities 4 Performing Arts 38-39 Earth Day Celebration 5 Sports 39-46 Arts & Crafts 6-9 Therapeutic Recreation 47 Equestrian Camps 9 Swim Lessons 48-51 Farm Life & Living History 10 Camp Indexes 52-63 General Day Camps & Theme Park Locations 64-65 Camps 11-18 Registration Information 66-67 Monmouth County Fair 19 Park Partners 68 Horticulture 20 Nature & Science 20-32 For summer camp registration information, see the inside front cover. -

The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – the Touring Years

1 THE BEATLES: EIGHT DAYS A WEEK – THE TOURING YEARS Release Dates U.S. Theatrical Release September 16 SVOD September 17 U.K., France and Germany (September 15). Australia and New Zealand (September 16) Japan (September 22) www.thebeatleseightdaysaweek.com #thebeatleseightdaysaweek Official Twitter handle: @thebeatles Facebook: facebook.com/thebeatles YouTube: youtube.com/thebeatles Official Beatles website: www.thebeatles.com PREFACE One of the prospects that drew Ron Howard to this famous story was the opportunity to give a whole new generation of people an insightful glimpse at what happened to launch this extraordinary phenomenon. One generation – the baby boomers - had a chance to grow up with The Beatles, and their children perhaps only know them vicariously through their parents. As the decades have passed The Beatles are still as popular as ever across all these years, even though many of the details of this story have become blurred. We may assume that all Beatles’ fans know the macro-facts about the group. The truth is, however, only a small fraction are familiar with the ins and outs of the story, and of course, each new generation learns about The Beatles first and foremost, from their music. So, this film is a chance to reintroduce a seminal moment in the history of culture, and to use the distance of time, to give us the chance to think about “the how and the why” this happened as it did. So, while this film has a lot of fascinating new material and research, first and foremost, it is a film for those who were “not there”, especially the millennials.