Trends in Breeding Phenology Across Ten Decades Show Varying Adjustments to Environmental Changes in Four Wader Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nordmann's Greenshank Population Analysis, at Pantai Cemara Jambi

Final Report Nordmann’s Greenshank Population Analysis, at Pantai Cemara Jambi Cipto Dwi Handono1, Ragil Siti Rihadini1, Iwan Febrianto1 and Ahmad Zulfikar Abdullah1 1Yayasan Ekologi Satwa Alam Liar Indonesia (Yayasan EKSAI/EKSAI Foundation) Surabaya, Indonesia Background Many shorebirds species have declined along East Asian-Australasian Flyway which support the highest diversity of shorebirds in the world, including the globally endangered species, Nordmann’s Greenshank. Nordmann’s Greenshank listed as endangered in the IUCN Red list of Threatened Species because of its small and declining population (BirdLife International, 2016). It’s one of the world’s most threatened shorebirds, is confined to the East Asian–Australasian Flyway (Bamford et al. 2008, BirdLife International 2001, 2012). Its global population is estimated at 500–1,000, with an estimated 100 in Malaysia, 100–200 in Thailand, 100 in Myanmar, plus unknown but low numbers in NE India, Bangladesh and Sumatra (Wetlands International 2006). The population is suspected to be rapidly decreasing due to coastal wetland development throughout Asia for industry, infrastructure and aquaculture, and the degradation of its breeding habitat in Russia by grazing Reindeer Rangifer tarandus (BirdLife International 2012). Mostly Nordmann’s Greenshanks have been recorded in very small numbers throughout Southeast Asia, and there are few places where it has been reported regularly. In Myanmar, for example, it was rediscovered after a gap of almost 129 years. The total count recorded by the Asian Waterbird Census (AWC) in 2006 for Myanmar was 28 birds with 14 being the largest number at a single locality (Naing 2007). In 2011–2012, Nordmann’s Greenshank was found three times in Sumatera Utara province, N Sumatra. -

Population Analysis and Community Workshop for Far Eastern Curlew Conservation Action in Pantai Cemara, Desa Sungai Cemara – Jambi

POPULATION ANALYSIS AND COMMUNITY WORKSHOP FOR FAR EASTERN CURLEW CONSERVATION ACTION IN PANTAI CEMARA, DESA SUNGAI CEMARA – JAMBI Final Report Small Grant Fund of the EAAFP Far Eastern Curlew Task Force Iwan Febrianto, Cipto Dwi Handono & Ragil S. Rihadini Jambi, Indonesia 2019 The aim of this project are to Identify the condition of Far Eastern Curlew Population and the remaining potential sites for Far Eastern Curlew stopover in Sumatera, Indonesia and protect the remaining stopover sites for Far Eastern Curlew by educating the government, local people and community around the sites as the effort of reducing the threat of habitat degradation, habitat loss and human disturbance at stopover area. INTRODUCTION The Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariencis) is the largest shorebird in the world and is endemic to East Asian – Australian Flyway. It is one of the Endangered migratory shorebird with estimated global population at 38.000 individual, although a more recent update now estimates the population at 32.000 (Wetland International, 2015 in BirdLife International, 2017). An analysis of monitoring data collected from around Australia and New Zealand (Studds et al. in prep. In BirdLife International, 2017) suggests that the species has declined much more rapidly than was previously thought; with an annual rate of decline of 0.058 equating to a loss of 81.7% over three generations. Habitat loss occuring as a result of development is the most significant threat currently affecting migratory shorebird along the EAAF (Melville et al. 2016 in EAAFP 2017). Loss of habitat at critical stopover sites in the Yellow Sea is suspected to be the key threat to this species and given that it is restricted to East Asian - Australasian Flyway, the declines in the non-breeding are to be representative of the global population. -

Tringarefs V1.3.Pdf

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2016 & 2017 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and best employed in conjunction with other reference sources. Grateful thanks to Graham Clarke (http://grahamsphoto.blogspot.com/) and Tom Shevlin (www.wildlifesnaps.com) for the cover images. All images © the photographers. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds). 2016. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 6.1 accessed February 2016]). Version Version 1.3 (March 2016). Cover Main image: Spotted Redshank. Albufera, Mallorca. 13th April 2011. Picture by Graham Clarke. Vignette: Solitary Sandpiper. Central Bog, Cape Clear Island, Co. Cork, Ireland. 29th August 2008. Picture by Tom Shevlin. Species Page No. Greater Yellowlegs [Tringa melanoleuca] 14 Green Sandpiper [Tringa ochropus] 16 Greenshank [Tringa nebularia] 11 Grey-tailed Tattler [Tringa brevipes] 20 Lesser Yellowlegs [Tringa flavipes] 15 Marsh Sandpiper [Tringa stagnatilis] 10 Nordmann's Greenshank [Tringa guttifer] 13 Redshank [Tringa totanus] 7 Solitary Sandpiper [Tringa solitaria] 17 Spotted Redshank [Tringa erythropus] 5 Wandering Tattler [Tringa incana] 21 Willet [Tringa semipalmata] 22 Wood Sandpiper [Tringa glareola] 18 1 Relevant Publications Bahr, N. 2011. The Bird Species / Die Vogelarten: systematics of the bird species and subspecies of the world. Volume 1: Charadriiformes. Media Nutur, Minden. Balmer, D. et al 2013. Bird Atlas 2001-11: The breeding and wintering birds of Britain and Ireland. -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

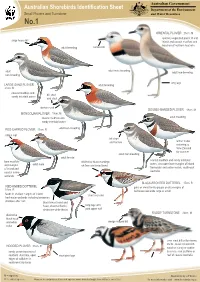

Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1

Australian Government Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1 ORIENTAL PLOVER 25cm. M sparsely vegetated plains of arid large heavy bill inland and coastal mudflats and beaches of northern Australia adult breeding narrow bill adult male breeding adult adult non-breeding non-breeding long legs LARGE SAND PLOVER adult breeding 21cm. M coastal mudflats and bill short sandy intertidal zones and stout darker mask DOUBLE-BANDED PLOVER 19cm. M MONGOLIAN PLOVER 19cm. M coastal mudflats and adult breeding sandy intertidal zones RED-CAPPED PLOVER 15cm. R adult non-breeding rufous cap bill short and narrow winter visitor returning to New Zealand for summer adult non-breeding adult female coastal mudflats and sandy intertidal bare mudflats distinctive black markings zones, also open bare margins of inland and margins adult male on face and breastband of inland and freshwater and saline marsh, south-east coastal saline Australia wetlands BLACK-FRONTED DOTTEREL 17cm. R RED-KNEED DOTTEREL pairs or small family groups on dry margins of 18cm. R feshwater wetlands large or small feeds in shallow margins of inland short rear end freshwater wetlands including temporary shallows after rain black breast band and head, chestnut flanks, long legs with distinctive white throat pink upper half RUDDY TURNSTONE 23cm. M distinctive black hood and white wedge shaped bill collar uses stout bill to flip stones, shells, seaweed and drift- 21cm. R HOODED PLOVER wood on sandy or cobble sandy ocean beaches of beaches, rock platform or southern Australia, open short pink legs reef of coastal Australia edges of saltlakes in south-west Australia M = migratory . -

202 Common Redshank Put Your Logo Here

Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here Put your logo here 202 Common Redshank Ruff Redshank. Spring. Adult (02-V) COMMON REDSHANK (Tringa totanus ) SEXING IDENTIFICATION Plumage of both sexes alike. 27-28 cm. In spring with brownish upperparts barred dark; white rump; white tail with dark bars; wings with a broad white band on the ed- AGEING ge; white underparts with dark streaks on head, This species is a scarce breeder in Aragon, so neck and breast; red bill with dark tip; orange- only 3 age classes can be recognized: red legs. In autumn with darker colours on up- 1st year autumn with fresh plumage; median perparts: grey tinge on breast. coverts spotted pale on edge; tertials brown with buff and dark marks; pointed tail feathers; breast slightly streaked; dull reddish base of bill; yellowish legs. 2nd year spring similar to adult ; this age can be recognized only in birds with some unmoul- ted median wing coverts and/or tertials; flight feathers moderately worn. Adult with median coverts with whitish edge and dark subterminal band; tertials grey brown with variable markings: either plain or with dark sepia bars, sometimes with extensive dark markings; rounded tail feathers; underparts with variable amount of dark barring and spot- ting; reddish legs and base of bill. Redshank . Pattern of wing, tail and bill. SIMILAR SPECIES Recalls a Spotted Redhsank in autumn , without a white patch on wings and has a longer bill; Redshank. Ruff has a narrower wing band and two whi- Ageing. te bands on sides of uppertail Pattern of bill: top adult; bot- Spotted tom 1st Redshank. -

Threatened Species List Spain

THREATENED SPECIES LIST SPAIN Threatened species included in the national inventory of the Ministry of MARM and/or in the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) that are or may be inhabited in the areas of our Hydro Power Stations. 6 CRITIC ENDANGERED SPECIES (CR) GROUP SPECIE COMMON NAME CATEGORY (MARM) (IUCN) Birds Neophron percnopterus Egyptian Vulture CR EN Botaurus stellaris Great Bittern CR LC Mammals Lynx pardinus Iberian Lynx CR CR Ursus arctos Brown Bear CR (Northern Spain) LC Invertebrates Belgrandiella galaica Gastropoda CR No listed Macromia splendens Splendid Cruiser CR VU 24 ENDANGERED SPECIES (EN) GROUP SPECIE COMMON NAME CATEGORY (MARM) (IUCN) Amphibians Rana dalmatina Agile Frog EN LC Birds Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Chough EN LC Hieraaetus fasciatus Bonelli´s Eagle EN LC Alectoris rufa Barbary Partridge EN LC Parus caeruleus Blue Tit EN LC Tyto alba Barn Owl EN LC Burhinus oedicnemus Stone Curlew EN LC Corvus corax Common Raven EN LC Chersophilus duponti Dupont´s Lark EN NT Milvus milvus Red Kite EN NT Aquila adalberti Spanish Imperial Eagle EN VU Cercotrichas galactotes Alzacola EN LC Reptiles Algyroides marchi Spanish Algyroides EN EN Emys orbicularis European Pond Turtle EN NT Mammals Rhinolophus mehelyi Mehely´s Horseshoe Bat EN VU Mustela lutreola European Mink EN EN Myotis capaccinii Long –Fingered bat EN VU Freshwater fish Salaria fluviatilis Freshwater blenny EN LC Chondrostoma turiense Madrija (Endemic) EN EN Cobitis vettonica Colmilleja del Alagón EN EN (Endemic) Invertebrates Gomphus -

Population Ecology of the Long-Billed Curlew (Numenius Americanus) in Western Idaho

POPULATION ECOLOGY OF THE LONG-BILLED CURLEW (NUMENIUS AMERICANUS) IN WESTERN IDAHO ROLAND L. REDMOND AND DONALD A. JENNI Departmentof Zoology,University of Montana,Missoula, Montana 59812 USA ABSTRACT.--IIlwestern Idaho, a breeding population of Long-billed Curlews (Numenius americanus)remained relatively stable over a 7-yr period.Productivity was monitored closely from 1977through 1979. Clutch mortality rates did not differ significantlyamong years, and meanclutch survival for a 32-daynesting period (4 daysegg laying and 28 daysincubation) was40% for all 3 yr combined.Females laid justone clutch(usually of 4 eggs)each season, and meanclutch size was significantlysmaller in 1979than in 1977and 1978.Estimated fledgingsuccess ranged from 0.40in 1977to 0.17in 1978and wasconsistently greater for femalesthat nestedearly eachseason. Mean annualadult survivalwas estimatedat 85% basedon resightingsof color-markedindividuals. Limited data for subadultsurvival pre- cludedcomplete demographic analysis. Nevertheless, given the estimatesof productivity and adult survivalpooled for 3 yr, survivalof subadultsfrom fledginguntil first breeding as3-year-olds needed to beonly 58% to maintainthe stablepopulation size observed through 1983. Received10 June1985, accepted 7 April 1986. THE population ecology of shorebirds (Cha- land et al. 1982), and Common Redshank (Yates radrii) is not well known, probably because 1982). Larger speciestend to be better studied many speciesare wary, breed in remote areas, during the nonbreeding season,and survival or both. Most thoroughly studied are species estimatesbased on annual returns to wintering that nest at temperate latitudes such as the Eur- grounds exist for Bar-tailed Godwits (Limosa asianOystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus; Goss- lapponica)and Eurasian Curlews (Numeniusar- Custard et al. 1982, Safriel et al. 1984), Common quata) (Evans and Pienkowski 1984). -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

MEDIA FACTSHEET C Migratory Bird Species at Sungei Buloh Wetland

MEDIA FACTSHEET C Migratory bird species at Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve is one of the sites along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway where an estimated 2,000 migratory shorebirds roost and feed at during the northern winter. Five of the commonly seen species at the Reserve include the Pacific Golden Plover (Pluvialis fulva), Lesser Sand Plover (Charadrius mongolus), Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus), Common Redshank (Tringa totanus) and Common Greenshank (Tringa nebularia). Globally threatened species s uch as Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariensis), and near threatened species such as Bar-tailed Godwit (Limosa lapponica) have also been recorded at the Reserve. 1 Pacific Golden Plover Pluvialis fulva Status in Singapore: common winter visitor and passage migrant Distinctive features: short bill and dark brown legs. Its non-breeding plumage is yellowish mottled greyish-brown upperparts and pale-brown underparts. Photo credit: National Parks Board 2 Lesser Sand Plover Charadrius mongolus Status in Singapore: common winter visitor and passage migrant Distinctive features: (non breeding plumage) underparts are white with dusky patches on sides of the breast, forming an incomplete breast-band. Page 1 of 7 For more information, please contact Ng Li-San (9846 7715). Photo credit: National Parks Board 3 Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus Status in Singapore: Common winter visitor and passage migrant Distinctive features: long down- curved bill (about twice the length as the head) and bluish-grey legs. Photo credit: National Parks Board 4 Common Redshank Tringa totanus Status in Singapore: Common winter visitor and passage migrant Distinctive features: long stout bill and long orange-red legs. Photo credit: National Parks Board Page 2 of 7 For more information, please contact Ng Li-San (9846 7715). -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Nest Trampling and Ground Nesting Birds: Quantifying Temporal and Spatial Overlap Between Cattle Activity and Breeding Redshank

Received: 8 May 2017 | Revised: 16 June 2017 | Accepted: 25 June 2017 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.3271 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Nest trampling and ground nesting birds: Quantifying temporal and spatial overlap between cattle activity and breeding redshank Elwyn Sharps1,2,3 | Jennifer Smart3,4 | Lucy R. Mason3 | Kate Jones3,5 | Martin W. Skov1 | Angus Garbutt2 | Jan G. Hiddink1 1School of Ocean Sciences, Bangor University, Menai Bridge, Anglesey, UK Abstract 2NERC Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Conservation grazing for breeding birds needs to balance the positive effects on veg- Environment Centre Wales, Bangor, Gwynedd, etation structure and negative effects of nest trampling. In the UK, populations of UK Common redshank Tringa totanus breeding on saltmarshes declined by >50% between 3RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, RSPB, Sandy, Bedfordshire, UK 1985 and 2011. These declines have been linked to changes in grazing management. 4School of Biological Sciences, University of The highest breeding densities of redshank on saltmarshes are found in lightly grazed East Anglia, Norwich, UK areas. Conservation initiatives have encouraged low- intensity grazing at <1 cattle/ha, 5Centre for Wildlife Assessment and Conservation, School of Biological but even these levels of grazing can result in high levels of nest trampling. If livestock Sciences, University of Reading, Reading, distribution is not spatially or temporally homogenous but concentrated where and Berkshire, UK when redshank breed, rates of nest trampling may be much higher than expected Correspondence based on livestock density alone. By GPS tracking cattle on saltmarshes and monitoring Elwyn Sharps, RSPB North Wales Office, Unit 14 Llys Castan, Parc Menai, Bangor, Gwynedd, trampling of dummy nests, this study quantified (i) the spatial and temporal distribution UK.