Artogeia) (Pieridae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of the Fall Webworm, Hyphantria

Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 6 172 International Journal of Biological Sciences 2010; 6(2):172-186 © Ivyspring International Publisher. All rights reserved Research Paper The complete mitochondrial genome of the fall webworm, Hyphantria cunea (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae) Fang Liao1,2, Lin Wang3, Song Wu4, Yu-Ping Li4, Lei Zhao1, Guo-Ming Huang2, Chun-Jing Niu2, Yan-Qun Liu4, , Ming-Gang Li1, 1. College of Life Sciences, Nankai University, Tianjin 300071, China 2. Tianjin Entry-Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau, Tianjin 300457, China 3. Beijing Entry-Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau, Beijing 101113, China 4. College of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Shenyang Agricultural University, Liaoning, Shenyang 110866, China Corresponding author: Y. Q. Liu, College of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Shenyang Agricultural University, Liaoning, Shenyang 110866, China; Tel: 86-24-88487163; E-mail: [email protected]. Or to: M. G. Li, College of Life Sciences, Nankai University, Tianjin 300071, China; Tel: 86-22-23508237; E-mail: [email protected]. Received: 2010.02.03; Accepted: 2010.03.26; Published: 2010.03.29 Abstract The complete mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) of the fall webworm, Hyphantria cunea (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae) was determined. The genome is a circular molecule 15 481 bp long. It presents a typical gene organization and order for completely sequenced lepidopteran mitogenomes, but differs from the insect ancestral type for the placement of tRNAMet. The nucleotide composition of the genome is also highly A + T biased, accounting for 80.38%, with a slightly positive AT skewness (0.010), indicating the occurrence of more As than Ts, as found in the Noctuoidea species. All protein-coding genes (PCGs) are initiated by ATN codons, except for COI, which is tentatively designated by the CGA codon as observed in other le- pidopterans. -

Révision Taxinomique Et Nomenclaturale Des Rhopalocera Et Des Zygaenidae De France Métropolitaine

Direction de la Recherche, de l’Expertise et de la Valorisation Direction Déléguée au Développement Durable, à la Conservation de la Nature et à l’Expertise Service du Patrimoine Naturel Dupont P, Luquet G. Chr., Demerges D., Drouet E. Révision taxinomique et nomenclaturale des Rhopalocera et des Zygaenidae de France métropolitaine. Conséquences sur l’acquisition et la gestion des données d’inventaire. Rapport SPN 2013 - 19 (Septembre 2013) Dupont (Pascal), Demerges (David), Drouet (Eric) et Luquet (Gérard Chr.). 2013. Révision systématique, taxinomique et nomenclaturale des Rhopalocera et des Zygaenidae de France métropolitaine. Conséquences sur l’acquisition et la gestion des données d’inventaire. Rapport MMNHN-SPN 2013 - 19, 201 p. Résumé : Les études de phylogénie moléculaire sur les Lépidoptères Rhopalocères et Zygènes sont de plus en plus nombreuses ces dernières années modifiant la systématique et la taxinomie de ces deux groupes. Une mise à jour complète est réalisée dans ce travail. Un cadre décisionnel a été élaboré pour les niveaux spécifiques et infra-spécifique avec une approche intégrative de la taxinomie. Ce cadre intégre notamment un aspect biogéographique en tenant compte des zones-refuges potentielles pour les espèces au cours du dernier maximum glaciaire. Cette démarche permet d’avoir une approche homogène pour le classement des taxa aux niveaux spécifiques et infra-spécifiques. Les conséquences pour l’acquisition des données dans le cadre d’un inventaire national sont développées. Summary : Studies on molecular phylogenies of Butterflies and Burnets have been increasingly frequent in the recent years, changing the systematics and taxonomy of these two groups. A full update has been performed in this work. -

Lepidopterologica Hungarica 1.Évf. 1.Sz. (2021.)

DOI: 10.24386/LepHung.2021.17.1.27 ISSN 2732–3854 (print) | ISSN 2732–3498 (online) Lepidopterologica Hungarica 17(1): 27–39. | https://epa.oszk.hu/04100/04137 27 Received 08.03.2021 | Accepted 13.03.2021 | Published 18.03.2021 Revision of Threatened Butterfly Species in Hungary (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera) Peter Gergely & Tamás Hudák Citation. Gergely P. & Hudák T. 2021: Revision of Threatened Butterfly Species in Hungary (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera). – Lepidopterologica Hungarica 17(1): 27–39. DOI: 10.24386/LepHung.2021.17.1.27 Abstract. The authors revise and update the threat and conservation status of butterflies in Hungary as origi- nally categorised in the Red Data Book (1999). The number of extinct and endangered species both in- creased during this period. Keywords. Hungary, butterfly, threat, conservation status Authors’ address. Peter Gergely | 2014 Csobánka, Hegyalja lépcső 4. | Hungary | E-mail: [email protected]; Tamás Hudák |1117 Budapest, Hamzsabégi út 13. | Hungary | E-mail: [email protected] Introduction The Red Data Book (van Swaay & Warren 1999) provided an up-to-date review of the threat and conservation status of all 576 butterfly species known to occur in Europe. It listed 6 extinct and 28 Threatened (2 Endangered, 8 Vulnerable and 18 Rare) butterfly species in Hungary (Table 1). The subsequent European Red List of Butterflies (van Swaay et al. 2010) contains only cumulative, European and European Union (EU27) data. Not unexpectedly, the current threat status of butterflies has worsened since then. A number of endangered species have become extinct, and some rare species deemed to be to be vulnerable or endangered. Even some species with former ‘Not Threatened’ status have become extinct or threatened. -

Download Article (PDF)

ISSN 0375-1511 Rec. zool. Surv. India: 112(part-3) : 101-112,2012 OBSERVATIONS ON THE STATUS AND DIVERSITY OF BUTTERFLIES IN THE FRAGILE ECOSYSTEM OF LADAKH 0 & K) AVTAR KAUR SIDHU, KAILASH CHANDRA* AND JAFER PALOT** High Altitude Regional Centre, Zoological Survey of India, Solan, H.P. * Zoological Survey of India,M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata 700 053. **Western Ghats Regional Centre, Zoological Survey of India, Calicut, Kerala INTRODUCTION between Zansker and Ladakh ranges and Nubra valley on the east side of Ladakh range crossing As one of the more inaccessible parts of the the Khardungla pass. The river Indus is the Himalayan Ranges, the cold deserts of India are backbone of Ladakh. resource poor regions. These could be considered as an important study area because of their As a distinct biome, this cold desert need extremely fragile ecosystem. The regions on the specially focused research and a concerted effort north flank of the Himalayas experience heavy in terms of natural resource management, snowfall and these remains virtually cut off from especially in the light of their vulnerable ecosystems the rest of the country for several months in the and highly deficient natural resource status. year. Summers are short. The proportion of oxygen Ecology and biodiversity of the Ladakh is under is less than in many other places at a comparable severe stress due to severe pressures. Ladakh and altitude because of lack of vegetation. There is little Kargil districts have been greatly disturbed since moisture to temper the effects of rarefied air. The 1962 because of extensive military activities. -

Some Butterfly Observations in the Karaganda Oblast of Kazakstan (Lepidoptera, Rhopalocera) by Bent Kjeldgaard Larsen Received 3.111.2003

©Ges. zur Förderung d. Erforschung von Insektenwanderungen e.V. München, download unter www.zobodat.at Atalanta (August 2003) 34(1/2): 153-165, colour plates Xl-XIVa, Wurzburg, ISSN 0171-0079 Some butterfly observations in the Karaganda Oblast of Kazakstan (Lepidoptera, Rhopalocera) by Bent Kjeldgaard Larsen received 3.111.2003 Abstract: Unlike the Ural Mountains, the Altai, and the Tien Shan, the steppe region of Cen tral Asia has been poorly investigated with respect to butterflies - distribution maps of the re gion's species (1994) show only a handful occurring within a 300 km radius of Karaganda in Central Kazakstan. It is therefore not surprising that approaching 100 additional species were discovered in the Karaganda Oblast during collecting in 1997, 2001 and 2002. During two days of collecting west of the Balkash Lake in May 1997, nine species were identified. On the steppes in the Kazakh Highland, 30 to 130 km south of Karaganda, about 50 butterflies were identified in 2001 and 2002, while in the Karkaralinsk forest, 200 km east of Karaganda, about 70 were encountered. Many of these insects are also to be found in western Europe and almost all of those noted at Karkaralinsk and on the steppes occur in South-Western Siberia. Observations revealed Zegris eupheme to be penetrating the area from the west and Chazara heydenreichi from the south. However, on the western side of Balkash Lake the picture ap peared to change. Many of the butterflies found here in 1997 - Parnassius apollonius, Zegris pyrothoe, Polyommatus miris, Plebeius christophi and Lyela myops - mainly came from the south, these belonging to the semi-desert and steppe fauna of Southern Kazakstan. -

The Endangered Butterfly Charonias Theano (Boisduval)(Lepidoptera

Neotropical Entomology ISSN: 1519-566X journal homepage: www.scielo.br/ne ECOLOGY, BEHAVIOR AND BIONOMICS The Endangered Butterfly Charonias theano (Boisduval) (Lepidoptera: Pieridae): Current Status, Threats and its Rediscovery in the State of São Paulo, Southeastern Brazil AVL Freitas1, LA Kaminski1, CA Iserhard1, EP Barbosa1, OJ Marini Filho2 1 Depto de Biologia Animal & Museu de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Univ Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brasil 2Centro de Pesquisa e Conservação do Cerrado e Caatinga – CECAT, Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade, Brasília, DF, Brasil Keywords Abstract Aporiina, Atlantic Forest, endangered species, Pierini, Serra do Japi The pierid Charonias theano Correspondence (Boisduval), an endangered butterfly André V L Freitas, Depto de Biologia Animal & species, has been rarely observed in nature, and has not been recorded Museu de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Univ in the state of CSão. theano Paulo in the last 50 years despite numerous efforts Estadual de Campinas, CP6109, 13083-970, Campinas, SP, Brasil; [email protected] to locate extant colonies. Based on museum specimens and personal information, was known from 26 sites in southeastern Edited by Kleber Del Claro – UFU and southern Brazil. Recently, an apparently viable population was recorded in a new locality, at Serra do Japi, Jundiaí, São Paulo, with Received 26 May 2011 and accepted 03 severalsince this individuals site represents observed one of during the few two large weeks forested in April, protected 2011. areas The August 2011 existence of this population at Serra do Japi is an important finding, São Paulo, but within its entire historical distribution. where the species could potentially persist not only in the state of Introduction In the last Brazilian red list of endangered fauna (Machado intensively sampled from 1987 to 1991, resulting in a list et al of 652 species (Brown 1992). -

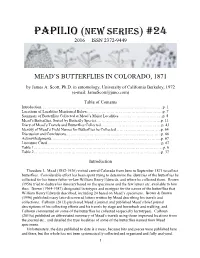

Papilio (New Series) #24 2016 Issn 2372-9449

PAPILIO (NEW SERIES) #24 2016 ISSN 2372-9449 MEAD’S BUTTERFLIES IN COLORADO, 1871 by James A. Scott, Ph.D. in entomology, University of California Berkeley, 1972 (e-mail: [email protected]) Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………..……….……………….p. 1 Locations of Localities Mentioned Below…………………………………..……..……….p. 7 Summary of Butterflies Collected at Mead’s Major Localities………………….…..……..p. 8 Mead’s Butterflies, Sorted by Butterfly Species…………………………………………..p. 11 Diary of Mead’s Travels and Butterflies Collected……………………………….……….p. 43 Identity of Mead’s Field Names for Butterflies he Collected……………………….…….p. 64 Discussion and Conclusions………………………………………………….……………p. 66 Acknowledgments………………………………………………………….……………...p. 67 Literature Cited……………………………………………………………….………...….p. 67 Table 1………………………………………………………………………….………..….p. 6 Table 2……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 37 Introduction Theodore L. Mead (1852-1936) visited central Colorado from June to September 1871 to collect butterflies. Considerable effort has been spent trying to determine the identities of the butterflies he collected for his future father-in-law William Henry Edwards, and where he collected them. Brown (1956) tried to deduce his itinerary based on the specimens and the few letters etc. available to him then. Brown (1964-1987) designated lectotypes and neotypes for the names of the butterflies that William Henry Edwards described, including 24 based on Mead’s specimens. Brown & Brown (1996) published many later-discovered letters written by Mead describing his travels and collections. Calhoun (2013) purchased Mead’s journal and published Mead’s brief journal descriptions of his collecting efforts and his travels by stage and horseback and walking, and Calhoun commented on some of the butterflies he collected (especially lectotypes). Calhoun (2015a) published an abbreviated summary of Mead’s travels using those improved locations from the journal etc., and detailed the type localities of some of the butterflies named from Mead specimens. -

Endemic Macrolepidoptera Subspecies in the Natural History Museum Collections from Sibiu (Romania)

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © 31 août «Grigore Antipa» Vol. LVI (1) pp. 65–80 2013 DOI: 10.2478/travmu-2013-0005 ENDEMIC MACROLEPIDOPTERA SUBSPECIES IN THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM COLLECTIONS FROM SIBIU (ROMANIA) SERGIU-CORNEL TÖRÖK, GABRIELA CUZEPAN Abstract. The paper presents data regarding endemic Macrolepidoptera subspecies preserved in the Entomological Collections of Natural History Museum from Sibiu. 22 endemic subspecies are recorded and represented by 382 specimens in the Entomological Collection. Most of the specimens have been collected from mountain habitats, especially from Southern and Western Carpathians. The results of this paper contribute to the improvement of the existing data concerning the distribution and outline the areas of Macrolepidoptera’s endemism in Romania. Résumé. Le document présente des données concernant les sous-espèces endémiques des Macrolépidoptères conservées dans les collections entomologiques du Musée d’Histoire Naturelle de Sibiu. 22 sous-espèces endémiques sont enregistrées et représentées par 382 spécimens dans la collection entomologique. La plupart des spécimens ont été recueillis dans les habitats de montagne, en particulier du Sud et l’Ouest des Carpates. Les résultats de cette étude contribuent à compléter les données existantes concernant la distribution et de définir les zones d’endémisme des Macrolépidoptères en Roumanie. Key words: Macrolepidoptera, endemic taxa, geographic distribution, museum collections. INTRODUCTION In this paper, the authors wish to present the endemic taxa from the Natural History Museum from Sibiu. The term endemic is used for taxa that are unique to a geographic location. This geographic location can be either relatively large or very small (Gaston & Spicer, 1998; Kenyeres et al., 2009). -

Butterflies & Flowers of the Kackars

Butterflies and Botany of the Kackars in Turkey Greenwings holiday report 14-22 July 2018 Led by Martin Warren, Yiannis Christofides and Yasemin Konuralp White-bordered Grayling © Alan Woodward Greenwings Wildlife Holidays Tel: 01473 254658 Web: www.greenwings.co.uk Email: [email protected] ©Greenwings 2018 Introduction This was the second year of a tour to see the wonderful array of butterflies and plants in the Kaçkar mountains of north-east Turkey. These rugged mountains rise steeply from Turkey’s Black Sea coast and are an extension of the Caucasus mountains which are considered by the World Wide Fund for Nature to be a global biodiversity hotspot. The Kaçkars are thought to be the richest area for butterflies in this range, a hotspot in a hotspot with over 160 resident species. The valley of the River Çoruh lies at the heart of the Kaçkar and the centre of the trip explored its upper reaches at altitudes of 1,300—2,300m. The area consists of steep-sided valleys with dry Mediterranean vegetation, typically with dense woodland and trees in the valley bottoms interspersed with small hay-meadows. In the upper reaches these merge into alpine meadows with wet flushes and few trees. The highest mountain in the range is Kaçkar Dağı with an elevation of 3,937 metres The tour was centred around the two charming little villages of Barhal and Olgunlar, the latter being at the fur- thest end of the valley that you can reach by car. The area is very remote and only accessed by a narrow road that winds its way up the valley providing extraordinary views that change with every turn. -

Logistic Regression Is a Better Method of Analysis Than

Scientific Notes 1183 LOGISTIC REGRESSION IS A BETTER METHOD OF ANALYSIS THAN LINEAR REGRESSION OF ARCSINE SQUARE ROOT TRANSFORMED PROPORTIONAL DIAPAUSE DATA OF PIERIS MELETE (LEPIDOPTERA: PIERIDAE) 1 2 3, P. J. SHI , H. S. SANDHU AND H. J. XIAO * 1Key Laboratory of Sustainable Development of Marine Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture, Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China 2University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Everglades Research and Education Center, Belle Glade, FL, USA 3Institute of Entomology, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang 330045, China *Corresponding author; E-mail: [email protected] Recently, Xiao et al. (2012) published a study the response variable are linear. However, non- on the effects of daily average temperature and linear effects are ubiquitous in nature. Therefore, natural day-length on the incidence of summer linear regression actually neglected the non- and winter diapause in the Cabbage Butterfly, linear effects, which led to low goodness-of-fit to Pieris melete Ménétriés (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). the objective data. Additionally, the proportional Under field conditions, the cabbage butterfly, data were arcsine square root transformed before Pieris melete, displays a pupal summer diapause performing the linear regression. Although this in response to relatively low daily temperatures transformation has long been standard procedure and gradually increasing day-length during in analyzing proportional data in ecology, logistic spring, and a pupal winter diapause in response regression has greater interpretability and high- to the progressively shorter day-length. To de- er power than transformation in data containing termine whether photoperiod has a stronger role binomial and non-binomial response variables than temperature in the determination of the (Warton & Hui 2011). -

BUTTERFLIES in Thewest Indies of the Caribbean

PO Box 9021, Wilmington, DE 19809, USA E-mail: [email protected]@focusonnature.com Phone: Toll-free in USA 1-888-721-3555 oror 302/529-1876302/529-1876 BUTTERFLIES and MOTHS in the West Indies of the Caribbean in Antigua and Barbuda the Bahamas Barbados the Cayman Islands Cuba Dominica the Dominican Republic Guadeloupe Jamaica Montserrat Puerto Rico Saint Lucia Saint Vincent the Virgin Islands and the ABC islands of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curacao Butterflies in the Caribbean exclusively in Trinidad & Tobago are not in this list. Focus On Nature Tours in the Caribbean have been in: January, February, March, April, May, July, and December. Upper right photo: a HISPANIOLAN KING, Anetia jaegeri, photographed during the FONT tour in the Dominican Republic in February 2012. The genus is nearly entirely in West Indian islands, the species is nearly restricted to Hispaniola. This list of Butterflies of the West Indies compiled by Armas Hill Among the butterfly groupings in this list, links to: Swallowtails: family PAPILIONIDAE with the genera: Battus, Papilio, Parides Whites, Yellows, Sulphurs: family PIERIDAE Mimic-whites: subfamily DISMORPHIINAE with the genus: Dismorphia Subfamily PIERINAE withwith thethe genera:genera: Ascia,Ascia, Ganyra,Ganyra, Glutophrissa,Glutophrissa, MeleteMelete Subfamily COLIADINAE with the genera: Abaeis, Anteos, Aphrissa, Eurema, Kricogonia, Nathalis, Phoebis, Pyrisitia, Zerene Gossamer Wings: family LYCAENIDAE Hairstreaks: subfamily THECLINAE with the genera: Allosmaitia, Calycopis, Chlorostrymon, Cyanophrys, -

An Appraisal of the Higher Classification of Cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadoidea) with Special Reference to the Australian Fauna

© Copyright Australian Museum, 2005 Records of the Australian Museum (2005) Vol. 57: 375–446. ISSN 0067-1975 An Appraisal of the Higher Classification of Cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadoidea) with Special Reference to the Australian Fauna M.S. MOULDS Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia [email protected] ABSTRACT. The history of cicada family classification is reviewed and the current status of all previously proposed families and subfamilies summarized. All tribal rankings associated with the Australian fauna are similarly documented. A cladistic analysis of generic relationships has been used to test the validity of currently held views on family and subfamily groupings. The analysis has been based upon an exhaustive study of nymphal and adult morphology, including both external and internal adult structures, and the first comparative study of male and female internal reproductive systems is included. Only two families are justified, the Tettigarctidae and Cicadidae. The latter are here considered to comprise three subfamilies, the Cicadinae, Cicadettinae n.stat. (= Tibicininae auct.) and the Tettigadinae (encompassing the Tibicinini, Platypediidae and Tettigadidae). Of particular note is the transfer of Tibicina Amyot, the type genus of the subfamily Tibicininae, to the subfamily Tettigadinae. The subfamily Plautillinae (containing only the genus Plautilla) is now placed at tribal rank within the Cicadinae. The subtribe Ydiellaria is raised to tribal rank. The American genus Magicicada Davis, previously of the tribe Tibicinini, now falls within the Taphurini. Three new tribes are recognized within the Australian fauna, the Tamasini n.tribe to accommodate Tamasa Distant and Parnkalla Distant, Jassopsaltriini n.tribe to accommodate Jassopsaltria Ashton and Burbungini n.tribe to accommodate Burbunga Distant.