1 Private Uriah Baldwin (Regimental Number 1846), Having No Known Last Resting-Place, Is Commemorated on the Bronze Beneath

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simcoe School War Memorial Stone

Simcoe School War Memorial Stone Overview The City of London Culture Office has been informed of a memorial stone that commemorates London soldiers that died during the First World War. Due to the nature of the memorial’s history, its location, ownership, and responsibility for its care are of concern to those that have brought this matter forward. Memorials are covered under the City of London’s definition of public art.1 This report will provide an overview of the Simcoe School War Memorial’s history, design, and significance, to assist in the resolution of this matter. History In 1887, Governor Simcoe School (later re-named Simcoe Street School) was built on the site of the last remaining log-house in London.2 See Figure 1 for a photograph of the original school building. This school was attended by a few notable Londoners, including Guy Lombardo, a famous Canadian violinist and the bandleader of The Royal Canadians. During the First World War, a number of past students from the Simcoe Street School volunteered for overseas duty for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Figure 1. Photograph of Simcoe Street School, also known as Governor Simcoe School. Source: “Simcoe Street School, London, Ontario,” Ivey Family London Room, London Public Library, London, Ontario, http://images.ourontario.ca/london/74863/data. After the war, many public schools in London felt the need to commemorate their former students that had died while serving overseas. Throughout the 1920s, schools across London commissioned the creation of memorial plaques and honour rolls. For example, honour rolls Simcoe School War Memorial Stone – Research Report 2 were commissioned for Wortley Road School, the former Empress Public School and Talbot Street School, Central Secondary School, Tecumseh Public School, South Secondary School, and Lorne Avenue Public School. -

On the Trail of the Newfoundland Caribou

On the Trail of the Newfoundland Caribou Patriotic Tour 2016 France & Belgium In Conjunction with the Churches of Newfoundland and Labrador June 26 - July 5, 2016 • 10 Days • 16 Meals Escorted by Rt. Rev. Dr. Geoff Peddle Anglican Bishop of the Diocese of Eastern Newfoundland and Labrador Caribou Monument at Beaumont Hamel A NEWFOUNDLAND PILGRIMAGE ON THE TRAIL OF THE CARIBOU The years 2014-2018 mark the 100th anniversaries of the First World War. We must never forget the tremendous contributions and horrendous sacrifices that so many Newfoundlanders and Labradorians made to that cause. Fighting in the uniforms of both the Navy and the Army, in the Merchant Marine and the Forestry Corps, our brave forebears never hesitated to stand in harm’s way to protect our homes, our families and our values. While many of them paid the supreme sacrifice, many more came home wounded in body and/or mind. We must also never forget the suffering at home of a generation for whom the effects of that war would be felt for the rest of their lives. The pastoral guidance was provided by many Newfoundland Padres who served the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, including Padre Tom Nangle who went on to become Newfoundland’s representative on the Imperial War Graves Commission. His vision brought the “Trail of the Caribou” to reality, and is the touchstone for many of those who wish to stand “where once they stood.” Knowing that many of those brave soldiers were members of our Newfoundland Churches, we have vowed to mark this important anniversary by a spiritual pilgrimage, to the battlefields of Europe in the summer of 2016. -

The Gate of Eternal Memories: Architecture Art and Remembrance

CONTESTED TERRAINS SAHANZ PERTH 2006 JOHN STEPHENS THE GATE OF ETERNAL MEMORIES: ARCHITECTURE ART AND REMEMBRANCE. John Richard Stephens Faculty of Built Environment Art and Design, Curtin University of Technology, Perth Western Australia, Australia. ABSTRACT The Menin Gate is a large memorial in Belgium to British Empire troops killed and missing during the battles of the Ypres Salient during the First World War. Designed by the architect Reginald Blomfield in 1922 it commemorates the 56,000 soldiers whose bodies were never found including 6,160 Australians. Blomfield’s sobering memorial has symbolic architectural meaning, and signifi- cance and commemorative meaning to relatives of those whose names appeared on the sur- faces of the structure. In 1927 the Australian artist and soldier William Longstaff painted his alle- gorical painting “Menin gate at Midnight showing the Gate as an ethereal structure in a brood- ing landscape populated with countless ghostly soldiers. The painting was an instant success and was reverentially exhibited at all Australian capital cities. From the contested terrain of war re- membrance this paper will argue that both the Gate and its representation in “Menin Gate at Midnight” are linked through the commemorative associations that each employ and have in common. “Here was the world’s worst wound. And Imperial War Graves cemetery. As a product of here with pride particular political and ethical policies, the bodies ‘Their name liveth for evermore’ the of British Empire soldiers were not returned to their Gateway claims. countries but buried close to where they met their Was ever an immolation so belied As these intolerably nameless names? fate. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

31Th March 2019 Hotspots

31TH MARCH 2019 HOTSPOTS 7 RACES IN FLANDERS FIELDS KM 85 KM 65 FURNES DIKSMUIDE START KORTEMARK TIELT DEINZE ROESBRUGGE-HARINGE KM 233 WAREGEM KM POPERINGE YPRES ZONNEBEKE 255 COURTRAI WEVELGEM HEUVELLAND MENIN ARRIVAL MESSINES COMINES-WARNETON PLOEGSTEERT KM 193 The map describes a limited number of hotspots. West-Flanders has 1,388 war remnants. This means that you can discover many other relics along the track, such as Locre No. 10 Cemetery, La Clytte Military Cemetery, Wulverghem-Lindenhoek Road Military Cemetery … the latter two provide a final resting place for more than 1,000 soldiers each. The ‘km’ marker indicates the distance to each hotspot from the starting position. - If the hotspot is located on the track (marked with ), then the kilometre marker indicates the track distance. - If the hotspot described is not located along the track, then the distance indicated will denote the distance from the starting point to the nearest kilometer marker on the track. These hotspots are located no further than 6.5 km from the track as the crow flies (men’s and ladies’ track combined). - For example, the Pool of Peace is not labelled with and is therefore a hotspot not on the track but nearby. This means that the hotspot is situated within a range of 6.5 km from the track. Specifically: the Pool of Peace is 1.75 km from the trail, on the road from Kemmel to Messines, at 164 km into the race. The ‘Commonwealth War Graves Commission’ (CWGC) is responsible for commemorating almost 1 700 000 British Com- monwealth soldiers who lost their lives in one of the two World Wars. -

A Monumental Past

KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT LEUVEN Faculty of Arts Institute for Cultural Studies A MONUMENTAL PAST AN EXPLORATION OF THE RELATION BETWEEN THE ENDURING POPULARITY OF THE MENIN GATE AND THE COMMEMORATION OF WORLD WAR ONE IN BRITAIN Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Cultural Studies Advisor by M. Bl eyen Myrthel Van Etterbeeck 2011-2012 ABSTRACT Wereldoorlog I gaf in Groot Brittannië aanleiding tot een groots herinneringsproject. Door een proces van selectie, articulatie, herhaling en weglating creëerde de Britten een gezuiverde herinnering aan het moeilijke verleden van de oorlog dat hen kon helpen bij het verwerken van verdriet en het eren en herdenken van de doden. Het Britse monument de Menenpoort, nabij het centrum van Ieper, is voortgekomen uit dit project en is gewijd aan de Britse soldaten die vermist raakten in de drie slagen bij Ieper. Sinds de oprichting, in 1927, komen mensen er samen om de gevallenen van de oorlog te herdenken. In zijn vijfentachtig jarige bestaan heeft het miljoenen bezoekers ontvangen en de laatste 30 jaar is het enkel in populariteit toegenomen. Deze thesis onderzoekt de relatie tussen de voortdurende populariteit van de Menenpoort en de Britse herdenking van, en herinneringen aan de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Daarbij word gebruik gemaakt van het theoretische kader van ‘memory studies’ met name de typologie van Aleida Assmann. Zij definieert sociale herinneringen als een vorm van herinneren die zich ontwikkelt tussen en gedeeld wordt door verschillende mensen maar gefundeerd blijft in geleefde ervaring. Deze vorm van herinneren kan een hele natie of generatie omspannen maar verdwijnt met zijn dragers. -

Jacqueline's Visit to the WW1 Battlefields of France and Flanders

Jacqueline’s Visit to the WW1 Battlefields of France and Flanders, 2004 An essay by Jacqueline Winspear The skylarks are far behind that sang over the down; I can hear no more those suburb nightingales; Thrushes and blackbirds sing in the gardens of the town In vain: the noise of man, beast, and machine prevails. —From “Good-Night” by Edward Thomas Thomas was killed in action at the Battle of Arras in 1917 Standing in a field close to the town of Serre in France, I heard a skylark high in the sky above and closed my eyes. They wrote of the skylarks—in letters, and some, in poems—those soldiers that lived and died in France during the Great War. The point at which I had stopped to listen was in the middle of a field that had been, in 1916, the no-man’s land between British and German front lines at the beginning of the Battle of the Somme. It was a terrible battle, one of the most devastating in a war that became, perhaps, the first defining human catastrophe of the twentieth century. I had finally made my pilgrimage to the battlefields of The Somme and Ypres, to the places where my grandfather had seen action in the First World War, and where, in 1916 he was severely wounded during the Battle of The Somme. Though the losses during the first few days of The Somme beggar belief—some 20,000 men from Canadian and Scottish regiments died during the first hour of fighting at the Beaumont Hamel/Newfoundland Park battlefield alone— the “battle” actually lasted 142 days, with a loss of more than 1,200,000 men from Britain, France, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Germany. -

Ypres Salient

Ypres Key Stage 3 Study Pack Contents The Ypres Salient The First Battle of Ypres The Second Battle of Ypres The Third Battle of Ypres The Fourth Battle of Ypres Ypres Town The Menin Gate Essex Farm Cemetery Hellfire Corner / Bayernwald Tyne Cot Cemetery Passchendaele Messines / Hill 60 The Pool of Peace Langemarck German Cemetery Sanctuary Wood / Hill 62 Poelcapelle St Julien / Hooge Crater Poperinge / Talbot House The Commonwealth War Graves Commission The Ypres Salient Definition: An outward bulge in a line of military attack or defence In 1914, as part of the Schlieffen Plan, the German army tried to sweep through Belgium, occupy the channel ports and encircle Paris. They were stopped by the British and French at Mons and the Marne and had to settle for a line of defences from Antwerp in the north to Belfort in the south. However, at Ypres, the Germans did occupy most of the high ground and could overlook allied positions. The town of Ypres lay just in front of the German line and was the key to the vital channel ports. Had the town fallen to the Germans, they would have been able to sweep through to the coast, preventing troops arriving from Britain and possibly controlling all shipping in the English Channel. Therefore, their constant aim in Belgium was to take Ypres from the British at all costs. “Ypres…A more sacred place for the British race does not exist in the world” – Winston Churchill 1919 The Ypres Salient The Ypres Salient 1. Why was Ypres so important to both sides? ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2. -

Ypres Resource 5

Resource 5 Why is Ypres such a focal point for First World War remembrance? What happened to Ypres after the War? After the War the Ypres was rebuilt using money paid by Germany in reparations, with the main square, including the Cloth Hall and town hall, being rebuilt as close to the original designs as possible. Life for the local people gradually started to return to normal after 4 years of constant fighting. British ex-soldiers and civilians were anxious that the sacrifices endured during the War were never forgotten. In the 1920s Ypres became a pilgrimage destination for the many veterans who had survived the War and who wanted to return to the area to remember their fallen comrades. The families of the dead also wanted to visit Ypres and spend time at the cemeteries and memorials remembering their relatives. Over time Ypres came to symbolise everything that Britain had fought for during the War and it took on an almost holy aura where visitors went to feel a personal connection with the spirits of the dead. Will Longstaff: The Menin Gate at Midnight, 1927 (This painting shows the ghosts of soldiers passing by the Gate at night) In July 1927 the memorial to the Missing in Ypres at the Menin Gate was opened in a ceremony attended by King George V, Lord Plumer who was in command of the Allied Armies during the 3rd Battle of Ypres in 1917, and by a group of 700 mothers who had lost sons during the War. In his speech at the opening ceremony Lord Plumer said of the names on the Gate: “He is not missing. -

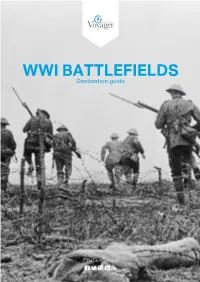

WWI BATTLEFIELDS Destination Guide

WWI BATTLEFIELDS Destination guide #BeThatTeacher 01273 827327 | voyagerschooltravel.com 1 Contents 3 Intro 4-7 History 7 Recreation 2 01273 827327 | voyagerschooltravel.com An introduction to the WWI Battlefields Intro In terms of battles of the First World War, or even of all time, the Somme and Ypres and regarded as amongst 2 of the most important and also most bloody. In the 21st century it is almost impossible to imagine the scale of the slaughter, with millions of lives lost in these 2 battles alone. The attritional nature of this type of warfare is quickly realised on a school tour, once a visit to a cemetery is followed by “it is almost another, or you read the names of the 72,000 men with no known grave on the sides of the Thiepval Memorial. impossible to The significance of these battles will be further understood imagine the scale of with visits to the battle sites themselves. Passchendaele is particularly moving, In Flanders Field Museum offers a huge the slaughter” volume of detail and attending the Last Post at the Menin Gate will give students a real sense of why remembrance is so important. All visits are covered by our externally verified Safety Management System and are pre-paid when applicable. Prices and opening times are accurate as of May 2018 and are subject to change and availability. Booking fees may apply to services provided by Voyager School Travel when paid on site. For the most accurate prices bespoke to your group size and travel date, please contact a Voyager School Travel tour coordinator at [email protected] 01273 827327 | voyagerschooltravel.com 3 The Menin Gate Memorial and Last Post as an “Every Man’s Club” for soldiers seeking an alternative to the “debauched” recreational life Ypres was the location of 5 major battles of the First of the town, Talbot House provided tea, cake and World War and the town was completely destroyed comfort for the Tommy for three years. -

THE MENIN GATE LIONS PRESS RELEASE ‘Menin Gate Lions’ Return Temporarily from Australia to Ieper

PRESS RELEASE THE MENIN GATE LIONS PRESS RELEASE ‘Menin Gate Lions’ return temporarily from Australia to Ieper 2017 is again an important year for Ieper within the context of commemorating ‘100 years of the First World War 2014-2018’. The first top moment will be the unveiling and inauguration of the stone ‘Menin Gate Lions ‘ during a special Last Post ceremony on Monday 24 April. At the same time, a small explanatory exhibition about the lions will be opened in the In Flanders Fields Museum. The two stone lions, which each hold a shield bearing the coat-of-arms of Ieper and after 1822 stood on the old staircase leading up to the entrance of the Cloth Hall, the civic and business centre of the city, will be temporarily returned to their original home as part of the commemoration of the First World War. In the middle of the 19th century, the lions were moved to a new position at the Menin Gate, where they stood during the First World War, while Ieper was reduced to ruins by German shells. Thousands of Australian and other Allied troops passed the lions on their way to the Belgian battlefields on the Western Front. Many of them were destined never to return. The lions, broken and damaged, were later recovered from the devastation and in 1936 they were gifted by the Burgomaster of Ieper to the Government of Australia as a gesture of friendship and gratitude for the sacrifices made by the Australian nation.Since then, they have stood guard at the entrance to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, where they have been admired by visitors from all over the world. -

Private Daniel D. Barrow (Regimental Number 2154) Is Interred in Vlamertinghe Military Cemetery: Grave Reference, IV

Private Daniel D. Barrow (Regimental Number 2154) is interred in Vlamertinghe Military Cemetery: Grave reference, IV. D. 6. His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a barkman at the at the Anglo- Newfoundland Development Company paper mill in Grand Falls, Daniel Barrow was a volunteer of the Eighth Recruitment Draft. He presented himself for medical examination on February 16 of 1916 in the same central Newfoundland industrial town of Grand Falls. It was a procedure which was to pronounce him as…Fit for Foreign Service. 1 It was then to be seven days later, on February 23, following that medical assessment and by that time having travelled to the Church Lads Brigade Armoury on Harvey Road in St. John’s, capital city of the Dominion of Newfoundland, that he was to enlist. Daniel Barrow was thereupon engaged at the daily private soldier’s rate of a single dollar, to which was to be added a ten-cent per diem Field Allowance. Twenty-four hours were now to pass before there then came the final formality of his enlistment: attestation. At the same venue on the 24th day of February he pledged his allegiance to the reigning monarch, George V, whereupon, at that moment, Daniel Barrow became…a soldier of the King. Private Barrow, Number 2154, would not sail to the United Kingdom until a further four weeks and a day had then elapsed. What the reasons might have been for this delay, or how he was to spend the lengthy waiting-period after his attestation, appear not to have been documented.