Oviposition of the Dobsonfly (Corydalus Cornutus, Megaloptera) on a Large River Author(S): Brian P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

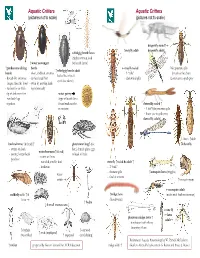

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Ag. Ento. 3.1 Fundamentals of Entomology Credit Ours: (2+1=3) THEORY Part – I 1

Ag. Ento. 3.1 Fundamentals of Entomology Ag. Ento. 3.1 Fundamentals of Entomology Credit ours: (2+1=3) THEORY Part – I 1. History of Entomology in India. 2. Factors for insect‘s abundance. Major points related to dominance of Insecta in Animal kingdom. 3. Classification of phylum Arthropoda up to classes. Relationship of class Insecta with other classes of Arthropoda. Harmful and useful insects. Part – II 4. Morphology: Structure and functions of insect cuticle, moulting and body segmentation. 5. Structure of Head, thorax and abdomen. 6. Structure and modifications of insect antennae 7. Structure and modifications of insect mouth parts 8. Structure and modifications of insect legs, wing venation, modifications and wing coupling apparatus. 9. Metamorphosis and diapause in insects. Types of larvae and pupae. Part – III 10. Structure of male and female genital organs 11. Structure and functions of digestive system 12. Excretory system 13. Circulatory system 14. Respiratory system 15. Nervous system, secretary (Endocrine) and Major sensory organs 16. Reproductive systems in insects. Types of reproduction in insects. MID TERM EXAMINATION Part – IV 17. Systematics: Taxonomy –importance, history and development and binomial nomenclature. 18. Definitions of Biotype, Sub-species, Species, Genus, Family and Order. Classification of class Insecta up to Orders. Major characteristics of orders. Basic groups of present day insects with special emphasis to orders and families of Agricultural importance like 19. Orthoptera: Acrididae, Tettigonidae, Gryllidae, Gryllotalpidae; 20. Dictyoptera: Mantidae, Blattidae; Odonata; Neuroptera: Chrysopidae; 21. Isoptera: Termitidae; Thysanoptera: Thripidae; 22. Hemiptera: Pentatomidae, Coreidae, Cimicidae, Pyrrhocoridae, Lygaeidae, Cicadellidae, Delphacidae, Aphididae, Coccidae, Lophophidae, Aleurodidae, Pseudococcidae; 23. Lepidoptera: Pieridae, Papiloinidae, Noctuidae, Sphingidae, Pyralidae, Gelechiidae, Arctiidae, Saturnidae, Bombycidae; 24. -

A New Fishfly Species (Megaloptera: Corydalidae: Chauliodinae) from Eocene Baltic Amber

Palaeoentomology 003 (2): 188–195 ISSN 2624-2826 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pe/ PALAEOENTOMOLOGY Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 2624-2834 (online edition) PE https://doi.org/10.11646/palaeoentomology.3.2.8 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:20A34D9A-DC69-453E-9662-0A8FAFA25677 A new fishfly species (Megaloptera: Corydalidae: Chauliodinae) from Eocene Baltic amber XINGYUE LIU1, * & JÖRG ANSORGE2 1College of Life Science and Technology, Hubei Engineering University, Xiaogan 432000, China �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9168-0659 2Institute of Geography and Geology, University of Greifswald, Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahnstraße 17a, D-17487 Greifswald, Germany �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1284-6893 *Corresponding author. �[email protected] Abstract and Sialidae (alderflies). Species of Megaloptera have worldwide distribution, but most of them occur mainly in The fossil record of Megaloptera (Insecta: Holometabola: subtropical and warm temperate regions, e.g., the Oriental, Neuropterida) is very limited. Both megalopteran families, i.e., Corydalidae and Sialidae, have been found in the Eocene Neotropical, and Australian Regions (Yang & Liu, 2010; Baltic amber, comprising two named species in one genus Liu et al., 2012, 2015a). The phylogeny and biogeography of Corydalidae (Chauliodinae) and four named species in of extant Megaloptera have been intensively studied in two genera of Sialidae. Here we report a new species of Liu et al. (2012, 2015a, b, 2016) and Contreras-Ramos Chauliodinae from the Baltic amber, namely Nigronia (2011). prussia sp. nov.. The new species possesses a spotted hind Compared with the other two orders of Neuropterida wing with broad band-like marking, a well-developed stem (Raphidioptera and Neuroptera), the fossil record of of hind wing MA subdistally with a short crossvein to MP, a Megaloptera is considerably scarce. -

Living Water. Eno River State Park: an Environmental Education Learning Experience Designed for the Middle Grades. INSTITUTION North Carolina State Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 376 024 SE 054 365 AUTHOR Hartley, Scott; Woods, Martha TITLE Living Water. Eno River State Park: An Environmental Education Learning Experience Designed for the Middle Grades. INSTITUTION North Carolina State Dept. of Environment, Health, and Natural Resources, Raleigh. Div. of Parks and Recreation. PUB DATE Oct 92 NOTE 96p.; For other Environmental Education Learning Experiences, see SE 054 364-371. AVAILABLE ,FROM North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation, P.O. Box 27687, Raleigh, NC 27611-7687. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Classification; Computation; Ecology; Entomology; Environmental Education; Experiential Learning; Field Trips; Grade 5; Grade 6; Integrated Activities; Intermediate Grades; Maps; *Marine Biology; Natural Resources; *Outdoor Activities; *Outdoor Education; Teaching Guides; Water Pollution; *Water Quality; *Water Resources IDENTIFIERS Dichotomous Keys; Environmental. Management; *North Carolina; pH; Rivers; State Parks; Water Quality Analysis; Watersheds ABSTRACT This learning packet, one in a series of eight, was developed by the Eno River State Park in North Carolina for Grades 5-6 to teach about various aspects of water life on the Eno River. Loose -leaf pages are presented in nine sections that contain: (1) introductions to the North Carolina State Park System, the Eno River State Park, and to the park's activity packet;(2) a summary of the activities that includes major concepts and objectives covered; (3) pre-visit activities on map trivia and dichotomous classification keys;(4) on-site activities on river flow, pH values, water bugs and river sediment;(5) post-visit activities on water pollution; (6)a list ol7 69 related vocabulary words; (7) park and parental permission forms for the visit; and (8) blank pages for taking notes. -

The Aquatic Neuropterida of Iowa

Entomology Publications Entomology 7-2020 The Aquatic Neuropterida of Iowa David E. Bowles National Park Service Gregory W. Courtney Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ent_pubs Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons The complete bibliographic information for this item can be found at https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ ent_pubs/576. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Entomology Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Aquatic Neuropterida of Iowa Abstract The fauna of aquatic Neuropterida of Iowa is documented. We list one species of dobsonfly, three species of fishflies, four alderflies (Megaloptera), and two spongillaflies (Neuroptera). New Iowa distributional records are reported for Protosialis americana (Rambur), Sialis joppa Ross, Sialis mohri Ross, Nigronia serricornis (Say), Climacia areolaris (Hagen), and Sisyra vicaria (Walker). Keywords Sialis, Chauliodes, Corydalus, Nigronia, Climacia, Sisyra Disciplines Ecology and Evolutionary Biology | Entomology Comments This article is published as Bowles, David E., and Gregory W. Courtney. "The Aquatic Neuropterida of Iowa." Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 122, no. 3 (2020): 556-565. doi: 10.4289/ 0013-8797.122.3.556. This article is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ent_pubs/576 PROC. ENTOMOL. -

Identifying Freshwater Ecosystems with Nationally Important Natural Heritage Values: Development of a Biogeographic Framework

Identifying freshwater ecosystems with nationally important natural heritage values: development of a biogeographic framework J.R. Leathwick, K. Collier and L. Chadderton SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 274 Published by Science & Technical Publishing Department of Conservation PO Box 10420, The Terrace Wellington 6143, New Zealand Cover: Ohinemuri River in Karangahake Gorge, Coromandel. Photo: John Leathwick. Science for Conservation is a scientific monograph series presenting research funded by New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). Manuscripts are internally and externally peer-reviewed; resulting publications are considered part of the formal international scientific literature. Individual copies are printed, and are also available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science & technical. © Copyright May 2007, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1173–2946 ISBN 978–0–478–14207–5 (hardcopy) ISBN 978–0–478–14208–2 (web PDF) This report was prepared for publication by Science & Technical Publishing; editing by Sue Hallas and layout by Lynette Clelland. Publication was approved by the Chief Scientist (Research, Development & Improvement Division), Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. ContEnts Abstract 5 1. Introduction 6 1.1 Water-bodies of national importance 6 1.2 Development -

Megaloptera of Canada 393 Doi: 10.3897/Zookeys.819.23948 REVIEW ARTICLE Launched to Accelerate Biodiversity Research

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 819: 393–396 (2019) Megaloptera of Canada 393 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.819.23948 REVIEW ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Megaloptera of Canada Xingyue Liu1 1 Department of Entomology, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China Corresponding author: Xingyue Liu ([email protected]) Academic editor: D. Langor | Received 29 January 2018 | Accepted 2 March 2018 | Published 24 January 2019 http://zoobank.org/E0BA7FB8-0318-4AC1-8892-C9AE978F90A7 Citation: Liu X (2019) Megaloptera of Canada. In: Langor DW, Sheffield CS (Eds) The Biota of Canada – A Biodiversity Assessment. Part 1: The Terrestrial Arthropods. ZooKeys 819: 393–396.https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.819.23948 Abstract An updated summary on the fauna of Canadian Megaloptera is provided. Currently, 18 species are re- corded in Canada, with six species of Corydalidae and 12 species of Sialidae. This is an increase of two species since 1979. An additional seven species are expected to be discovered in Canada. Barcode Index Numbers are available for ten Canadian species. Keywords alderflies, biodiversity assessment, Biota of Canada, dobsonflies, fishflies, Megaloptera The order Megaloptera (dobsonflies, fishflies, and alderflies) is one of the three orders of Neuropterida, and is characterized by the prognathous adult head, the broad anal area of hind wing and the exclusively aquatic larval stages (New and Theischinger 1993). Currently, there are ca. 380 described species of Megaloptera worldwide (Yang and Liu 2010, Oswald 2016). Extant Megaloptera are composed of only two families; Corydalidae, which is divided into Corydalinae (dobsonflies) and Chauliodinae (fish- flies), and Sialidae (alderflies). -

Systematics and Biogeography of the Dobsonfly Genus Neurhermes Navás (Megaloptera: Corydalidae: Corydalinae)

73 (1): 41 – 63 29.4.2015 © Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, 2015. Systematics and biogeography of the dobsonfly genus Neurhermes Navás (Megaloptera: Corydalidae: Corydalinae) Xingyue Liu *, 1, Fumio Hayashi 2 & Ding Yang *, 1 1 Department of Entomology, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China; Xingyue Liu [[email protected]]; Ding Yang [[email protected]] — 2 Department of Biology, Tokyo Metropolitan University, Minamiosawa 1-1, Hachioji, Tokyo 192-0397, Japan; Fumio Hayashi [[email protected]] — * Corresponding authors Accepted 29.ix.2014. Published online at www.senckenberg.de/arthropod-systematics on 17.iv.2015. Abstract The Oriental dobsonfly genus Neurhermes Navás is one of the most impressive megalopterans because of the striking coloration and marking patterns, which probably imitate some diurnal toxic moths. In this paper, all seven species of Neurhermes are described or re- described, and illustrated, with a new species, namely Neurhermes nigerescens sp.n., described from northeastern India. Lectotypes of Neurhermes costatostriata (van der Weele, 1907) and Neurhermes tonkinensis (van der Weele, 1909) are herein designated. Neurhermes bipunctata Yang & Yang, 1988 is treated as a junior synonym of Neurhermes selysi (van der Weele, 1909). A phylogeny of Neurhermes is reconstructed based on the morphological data of the adults. Combining this phylogeny and the geographical distribution, Neurhermes is considered to have an origin and a historically widespread distribution in southern Eurasia at least during Eocene. The speciation within Neurhermes might have happened because of the Tertiary orogenic events after the collision between the Indian subcontinent and Eurasia. The separation of Sundaland from Eurasia and the island formation within Sundaland possibly shaped the fauna within the clade comprising the species, i.e. -

Megaloptera : Corydalidae

Systematic Entomology (1981) 6, 253--290 Systematics of the dobsonfly subfamily Corydalinae (Megaloptera :Corydalidae) MICHAEL J. GLORIOSO* Department of Entomology, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, U.S.A. ABSTRACT. The genera of Corydalinae are redefined, and representative characters are figured for each genus. New character sources, such as mouthparts and internal female genitalia, are investigated, as well as traditional male genitalia and wings. Allohermes is synonymized with Protohermes, Doeringia with Platy- neuromus. Intergeneric relationships are hypothesized on the basis of a cladistic analysis. Acanthacorydalis and the New World genera form a monophyletic group, as do Protohermes and Neurhermes, and Neuromus and Neoneuromus. Chloroniella belongs in the Acanthacorydalis - New World lineage, but exact placement is uncertain. A phyletic sequence classification is proposed on the basis of the cladistic analysis. Introduction American Covydulus cornutus are excellent angling bait, while dried larvae of Pvotoizevmes The Megaloptera, long considered among the grandis, referred to as 'magotaro mushi', were most primitive of holometabolous insects considered a remedy for infant emotional (Weele, 191 O), contains two families, Sialidae irritation in Japan (Kuwayama, 1962). and Corydalidae. The Corydalidae, easily Relationships within the Corydalinae are separated from the Sialidae by presence of poorly understood, and generic limits are ocelli, non-bilobed fourth tarsomeres, and poorly defined. In this study I redefine the large size, contains two subfamilies, Coryda- genera and postulate intergeneric relation- linae and Chauliodinae. The Corydalinae are ships based on shared derived character states, restricted to North and South America, South or synapotypies. In searching for sufficient Africa and Asia, while the Chauliodinae also characters to more confidently establish occur in Australia and New Zealand. -

Aquatic Insect Family Tree

Aquatic Insect Family Tree Aquatic insects are like other insects. cacarryararrryrr itsiti own o house oof pebbles and sticks They have six legs, threeee bobody segments, everywhere it goes! antennae, and sometimestim wings. They also Aquatic insects are different in one way have an exoskeletonon (a skeleton on the from the insinsects we see on land. They are outside of the body).ody). That helps them movmove adapted to liveve part of their lives underwater. food and objectsts much heavier than thetheir This family tree showsho some of the aquatic own weight. A caddisfly larvae can mmake and insect groups. Kingdom: Phylum: Class: Animalia Arthropoda Insecta (animals) (jointed-foot invertebrates) (insects) Mayflies (Ephemeroptera) Stoneflies (Plecoptera) Giant stonefly nymph; roach stonefly nymph; common stonefly nymph Left to right: Burrowing mayfly nymph; minnow mayfly nymph; flat-headed mayfly nymph Dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata) Above: Common stonefly nymph Left to right: Dragonfly nymph; damsel- fly nymph Alderflies, dobsons and fishflies True bugs (Hemiptera) (Megaloptera) Left to right: Dobsonfly larva (hellgrammite); alderfly larva Caddisflies (Trichoptera) Top to bottom (left to right): Water strider; water boatman; backswim- mer; water scorpion; giant water bug True flies (Diptera) Cranefly larva; mosquito larvae; blackfly larva Top: Stick case-maker caddisfly larva Bottom left to right: Stone case-maker caddisfly larva; net- spinning caddisfly larva Left to right: Cranefly larva; blackfly larva Beetles (Coleoptera) Left to right: Water penny (larva); whirligig beetle; predaceous diving beetle. -

Transcript for up the Creek Written by Nicholas Oldland (Kids Can Press)

Transcript for Up the Creek written by Nicholas Oldland (Kids Can Press) Introduction (approximately 0:00 – 4:05) Hi everyone! It's Colleen from the KU Natural History Museum, and I am here for today's Story Book Science. We will be reading Up the Creek by Nicholas Oldland. I do want to give a little bit of time for people to join us. So while we wait I do want to remind you about the activity that we'll do at the end of the reading and after we've looked at some specimens. So if you don't have a piece of paper: go grab one! It can be anything. I'm using a part of a paper bag. It can be any scrap piece of paper, um, anything that you would be totally fine with, um, if it were to be ripped apart. So if you don't have that, please go grab one; and while we wait, what we are going to do is, we're going to look at the cover of the book. So this is the cover of the book. We have three animals on the cover, and these animals, they are paddling up a creek to go on an adventure. One of the things I want you to think about is the creek itself. Do you think the animals want to canoe in a clean creek? Or do you think they want to canoe in a dirty creek? I also want you to think about what type of creek you would want to canoe or swim in or walk by or even just look at a picture of. -

Indiana 4-H Entomology Insect Flash Cards

PURDUE EXTENSION ID-411 Indiana 4-H Entomology Insect Flash Cards Flash cards can be an effective tool to Concentrate follow-up study efforts on help students learn to identify insects the cards that each learner had the most and insect facts. Use the following pages problems with (the “uncertain” and to make flash cards by cutting the “don't know” piles). Make this into horizontal lines, gluing one side, then a game to see who can get the largest folding each in half. It can be “know” pile on the first go-through. especially effective to have a peer educator (student showing the cards who The insects included in these flash cards can see the answers) count to five for are all found in Indiana and used each card. If the learner gets it right, it in the Indiana 4-H/FFA Entomology goes in a "know" pile; if it takes a little Career Development Event. longer, put the card in an "uncertain" pile; and if the learner doesn't know, put the card in a "don't know" pile. Authors: Tim Gibb, Natalie Carroll Editor: Becky Goetz Designer: Jessica Seiler Graduate Student Assistant: Terri Hoctor Common Name – Order Name 1. Alfalfa weevil - Coleoptera 76. Japanese beetle - Coleoptera All Insects 2. American cockroach - Dictyoptera 77. June beetle - Coleoptera 3. Angoumois grain moth - Lepidoptera 78. Katydid - Orthoptera 4. Annual cicada - Homoptera 79. Lace bug - Hemiptera Pictured 5. Antlion - Neuroptera 80. Lady beetle - Coleoptera 6. Aphid - Homoptera 81. Locust leafminer - Coleoptera 7. Apple maggot fly - Diptera 82. Longhorned beetle - Coleoptera 8.