Dobsonflies Look Vicious

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aquatic Insects Are Dramatically Underrepresented in Genomic Research

insects Communication Aquatic Insects Are Dramatically Underrepresented in Genomic Research Scott Hotaling 1,* , Joanna L. Kelley 1 and Paul B. Frandsen 2,3,* 1 School of Biological Sciences, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84062, USA 3 Data Science Lab, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20002, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (P.B.F.); Tel.: +1-(828)-507-9950 (S.H.); +1-(801)-422-2283 (P.B.F.) Received: 20 August 2020; Accepted: 3 September 2020; Published: 5 September 2020 Simple Summary: The genome is the basic evolutionary unit underpinning life on Earth. Knowing its sequence, including the many thousands of genes coding for proteins in an organism, empowers scientific discovery for both the focal organism and related species. Aquatic insects represent 10% of all insect diversity, can be found on every continent except Antarctica, and are key components of freshwater ecosystems. However, aquatic insect genome biology lags dramatically behind that of terrestrial insects. If genomic effort was spread evenly, one aquatic insect genome would be sequenced for every ~9 terrestrial insect genomes. Instead, ~24 terrestrial insect genomes have been sequenced for every aquatic insect genome. A lack of aquatic genomes is limiting research progress in the field at both fundamental and applied scales. We argue that the limited availability of aquatic insect genomes is not due to practical limitations—small body sizes or overly complex genomes—but instead reflects a lack of research interest. We call for targeted efforts to expand the availability of aquatic insect genomic resources to empower future research. -

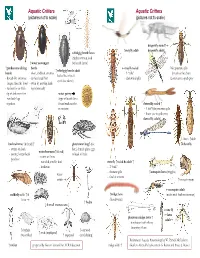

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Ag. Ento. 3.1 Fundamentals of Entomology Credit Ours: (2+1=3) THEORY Part – I 1

Ag. Ento. 3.1 Fundamentals of Entomology Ag. Ento. 3.1 Fundamentals of Entomology Credit ours: (2+1=3) THEORY Part – I 1. History of Entomology in India. 2. Factors for insect‘s abundance. Major points related to dominance of Insecta in Animal kingdom. 3. Classification of phylum Arthropoda up to classes. Relationship of class Insecta with other classes of Arthropoda. Harmful and useful insects. Part – II 4. Morphology: Structure and functions of insect cuticle, moulting and body segmentation. 5. Structure of Head, thorax and abdomen. 6. Structure and modifications of insect antennae 7. Structure and modifications of insect mouth parts 8. Structure and modifications of insect legs, wing venation, modifications and wing coupling apparatus. 9. Metamorphosis and diapause in insects. Types of larvae and pupae. Part – III 10. Structure of male and female genital organs 11. Structure and functions of digestive system 12. Excretory system 13. Circulatory system 14. Respiratory system 15. Nervous system, secretary (Endocrine) and Major sensory organs 16. Reproductive systems in insects. Types of reproduction in insects. MID TERM EXAMINATION Part – IV 17. Systematics: Taxonomy –importance, history and development and binomial nomenclature. 18. Definitions of Biotype, Sub-species, Species, Genus, Family and Order. Classification of class Insecta up to Orders. Major characteristics of orders. Basic groups of present day insects with special emphasis to orders and families of Agricultural importance like 19. Orthoptera: Acrididae, Tettigonidae, Gryllidae, Gryllotalpidae; 20. Dictyoptera: Mantidae, Blattidae; Odonata; Neuroptera: Chrysopidae; 21. Isoptera: Termitidae; Thysanoptera: Thripidae; 22. Hemiptera: Pentatomidae, Coreidae, Cimicidae, Pyrrhocoridae, Lygaeidae, Cicadellidae, Delphacidae, Aphididae, Coccidae, Lophophidae, Aleurodidae, Pseudococcidae; 23. Lepidoptera: Pieridae, Papiloinidae, Noctuidae, Sphingidae, Pyralidae, Gelechiidae, Arctiidae, Saturnidae, Bombycidae; 24. -

A New Fishfly Species (Megaloptera: Corydalidae: Chauliodinae) from Eocene Baltic Amber

Palaeoentomology 003 (2): 188–195 ISSN 2624-2826 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pe/ PALAEOENTOMOLOGY Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 2624-2834 (online edition) PE https://doi.org/10.11646/palaeoentomology.3.2.8 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:20A34D9A-DC69-453E-9662-0A8FAFA25677 A new fishfly species (Megaloptera: Corydalidae: Chauliodinae) from Eocene Baltic amber XINGYUE LIU1, * & JÖRG ANSORGE2 1College of Life Science and Technology, Hubei Engineering University, Xiaogan 432000, China �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9168-0659 2Institute of Geography and Geology, University of Greifswald, Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahnstraße 17a, D-17487 Greifswald, Germany �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1284-6893 *Corresponding author. �[email protected] Abstract and Sialidae (alderflies). Species of Megaloptera have worldwide distribution, but most of them occur mainly in The fossil record of Megaloptera (Insecta: Holometabola: subtropical and warm temperate regions, e.g., the Oriental, Neuropterida) is very limited. Both megalopteran families, i.e., Corydalidae and Sialidae, have been found in the Eocene Neotropical, and Australian Regions (Yang & Liu, 2010; Baltic amber, comprising two named species in one genus Liu et al., 2012, 2015a). The phylogeny and biogeography of Corydalidae (Chauliodinae) and four named species in of extant Megaloptera have been intensively studied in two genera of Sialidae. Here we report a new species of Liu et al. (2012, 2015a, b, 2016) and Contreras-Ramos Chauliodinae from the Baltic amber, namely Nigronia (2011). prussia sp. nov.. The new species possesses a spotted hind Compared with the other two orders of Neuropterida wing with broad band-like marking, a well-developed stem (Raphidioptera and Neuroptera), the fossil record of of hind wing MA subdistally with a short crossvein to MP, a Megaloptera is considerably scarce. -

Living Water. Eno River State Park: an Environmental Education Learning Experience Designed for the Middle Grades. INSTITUTION North Carolina State Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 376 024 SE 054 365 AUTHOR Hartley, Scott; Woods, Martha TITLE Living Water. Eno River State Park: An Environmental Education Learning Experience Designed for the Middle Grades. INSTITUTION North Carolina State Dept. of Environment, Health, and Natural Resources, Raleigh. Div. of Parks and Recreation. PUB DATE Oct 92 NOTE 96p.; For other Environmental Education Learning Experiences, see SE 054 364-371. AVAILABLE ,FROM North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation, P.O. Box 27687, Raleigh, NC 27611-7687. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Classification; Computation; Ecology; Entomology; Environmental Education; Experiential Learning; Field Trips; Grade 5; Grade 6; Integrated Activities; Intermediate Grades; Maps; *Marine Biology; Natural Resources; *Outdoor Activities; *Outdoor Education; Teaching Guides; Water Pollution; *Water Quality; *Water Resources IDENTIFIERS Dichotomous Keys; Environmental. Management; *North Carolina; pH; Rivers; State Parks; Water Quality Analysis; Watersheds ABSTRACT This learning packet, one in a series of eight, was developed by the Eno River State Park in North Carolina for Grades 5-6 to teach about various aspects of water life on the Eno River. Loose -leaf pages are presented in nine sections that contain: (1) introductions to the North Carolina State Park System, the Eno River State Park, and to the park's activity packet;(2) a summary of the activities that includes major concepts and objectives covered; (3) pre-visit activities on map trivia and dichotomous classification keys;(4) on-site activities on river flow, pH values, water bugs and river sediment;(5) post-visit activities on water pollution; (6)a list ol7 69 related vocabulary words; (7) park and parental permission forms for the visit; and (8) blank pages for taking notes. -

Phylogeny of Endopterygote Insects, the Most Successful Lineage of Living Organisms*

REVIEW Eur. J. Entomol. 96: 237-253, 1999 ISSN 1210-5759 Phylogeny of endopterygote insects, the most successful lineage of living organisms* N iels P. KRISTENSEN Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen 0, Denmark; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Insecta, Endopterygota, Holometabola, phylogeny, diversification modes, Megaloptera, Raphidioptera, Neuroptera, Coleóptera, Strepsiptera, Díptera, Mecoptera, Siphonaptera, Trichoptera, Lepidoptera, Hymenoptera Abstract. The monophyly of the Endopterygota is supported primarily by the specialized larva without external wing buds and with degradable eyes, as well as by the quiescence of the last immature (pupal) stage; a specialized morphology of the latter is not an en dopterygote groundplan trait. There is weak support for the basal endopterygote splitting event being between a Neuropterida + Co leóptera clade and a Mecopterida + Hymenoptera clade; a fully sclerotized sitophore plate in the adult is a newly recognized possible groundplan autapomorphy of the latter. The molecular evidence for a Strepsiptera + Díptera clade is differently interpreted by advo cates of parsimony and maximum likelihood analyses of sequence data, and the morphological evidence for the monophyly of this clade is ambiguous. The basal diversification patterns within the principal endopterygote clades (“orders”) are succinctly reviewed. The truly species-rich clades are almost consistently quite subordinate. The identification of “key innovations” promoting evolution -

Chapter X —Order Megaloptera

Chapter X —Order Megaloptera (Alderflies- , Dobsonflies- , Fishflies- ) • (Williams & Feltmate, 1992) • Superphylum Arthropoda • (jointed-legged metazoan animals [Gr, arthron = joint; pous = foot]) • Phylum Entoma • Subphylum Uniramia • (L, unus = one; ramus = branch, referring to the unbranched nature of the ap- pendages) • Superclass Hexapoda • (Gr, hex = six, pous = foot) • Class Insecta • (L, insectum meaning cut into sections) • Subclass Ptilota • Infraclass Neopterygota The order Megaloptera is a small order of insects in the infraclass Neoptera, division Endoptery- gota. The Megaloptera are closely related to the Neuroptera (spongillaflies). The Megaloptera comprise only two families, the Corydalidae (fishflies and dobsonflies) and the Sialidae (alderflies). Larvae of all species of Megaloptera are aquatic and attain the largest size of all aquatic insects. Larval Corydalidae are sometimes called hellgrammites or toe biters. The adult Corydalidae are large, having a wing span of up to 16 cm (Megaloptera = “large wing”). Life History Females of this holometabolous order lay elongate eggs in masses on vegetation overhanging the aquatic habitat, on large rocks projecting from the water, or on bridge abutments. After about a week at cool temperatures, eggs hatch at night and first-instar larvae fall into the water. As young larvae swallow air, gas bubbles form in their guts, possibly providing the buoyancy neces- sary to transport to riffles first instars that land in pools. The metabolic consequences of this air bubble are unknown for most species. Megalopteran larvae go through 10-12 instars before crawling out of the water onto shore to pupate. Some have been reported to pupate as far as 50 metres from the shore. Bioassessment of Freshwaters using Benthic Macroinvertebrates- A Primer X-1 Most sialids have one- or two-year life cycles, whereas corydalids in cold mountain streams and in intermittent streams may live for up to five years. -

New Distribution Records of Fishflies (Megaloptera: Corydalidae) for Kentucky, U.S.A.1

40 ENTOMOLOGICAL NEWS Volume 117, Number 1, January and February 2006 41 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS NEW DISTRIBUTION RECORDS OF FISHFLIES The authors are deeply indebted to Professors J. H. Martin and R. L. Blackman for providing a (MEGALOPTERA: CORYDALIDAE) visiting position to the first author. Professor Blackman also helped examine the specimens. Miss 1 Kun Guo collected some of the material used in this study and Miss Caiping Liu prepared the micro- FOR KENTUCKY, U.S.A. scope slides. The project is supported by the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (Grant 2 3 4 5 No.30270171, No. 30570214), and National Science Fund for Fostering Talents in Basic Research Donald C. Tarter, Dwight L. Chaffee, Charles V. Covell Jr., and Sean T. O’Keefe (No. NSFC-J0030092). KEY WORDS: Megaloptera, fishflies, Kentucky, county records, Kentucky, U.S.A. ABSTRACT: New distributional records (74) of larval fishflies are reported for Kentucky. Twenty- LITERATURE CITED five new county records were added for Nigronia serricornis (Say), and forty-two new county records were added for N. fasciatus (Walker), the most widely distributed fishfly in Kentucky (54 Agarwala, B. K. and D. N. Raychaudhuri. 1977. Two new species of aphids (Homoptera: Aphi- counties). These two species were sympatric in 14 streams in eastern Kentucky. One new county didae) from Sikkim, North east India. Entomon 2(1): 77-80. record was added for Neohermes concolor (Davis). Four new county records were noted for Chau- Baker, A. 1920. Generic classification of the hemipterous family Aphididae. Bulletin of the United liodes pectinicornis (Linnaeus), while two new county records were added for C. -

The Aquatic Neuropterida of Iowa

Entomology Publications Entomology 7-2020 The Aquatic Neuropterida of Iowa David E. Bowles National Park Service Gregory W. Courtney Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ent_pubs Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons The complete bibliographic information for this item can be found at https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ ent_pubs/576. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Entomology Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Aquatic Neuropterida of Iowa Abstract The fauna of aquatic Neuropterida of Iowa is documented. We list one species of dobsonfly, three species of fishflies, four alderflies (Megaloptera), and two spongillaflies (Neuroptera). New Iowa distributional records are reported for Protosialis americana (Rambur), Sialis joppa Ross, Sialis mohri Ross, Nigronia serricornis (Say), Climacia areolaris (Hagen), and Sisyra vicaria (Walker). Keywords Sialis, Chauliodes, Corydalus, Nigronia, Climacia, Sisyra Disciplines Ecology and Evolutionary Biology | Entomology Comments This article is published as Bowles, David E., and Gregory W. Courtney. "The Aquatic Neuropterida of Iowa." Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 122, no. 3 (2020): 556-565. doi: 10.4289/ 0013-8797.122.3.556. This article is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ent_pubs/576 PROC. ENTOMOL. -

Identifying Freshwater Ecosystems with Nationally Important Natural Heritage Values: Development of a Biogeographic Framework

Identifying freshwater ecosystems with nationally important natural heritage values: development of a biogeographic framework J.R. Leathwick, K. Collier and L. Chadderton SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 274 Published by Science & Technical Publishing Department of Conservation PO Box 10420, The Terrace Wellington 6143, New Zealand Cover: Ohinemuri River in Karangahake Gorge, Coromandel. Photo: John Leathwick. Science for Conservation is a scientific monograph series presenting research funded by New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). Manuscripts are internally and externally peer-reviewed; resulting publications are considered part of the formal international scientific literature. Individual copies are printed, and are also available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science & technical. © Copyright May 2007, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1173–2946 ISBN 978–0–478–14207–5 (hardcopy) ISBN 978–0–478–14208–2 (web PDF) This report was prepared for publication by Science & Technical Publishing; editing by Sue Hallas and layout by Lynette Clelland. Publication was approved by the Chief Scientist (Research, Development & Improvement Division), Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. ContEnts Abstract 5 1. Introduction 6 1.1 Water-bodies of national importance 6 1.2 Development -

Megaloptera of Canada 393 Doi: 10.3897/Zookeys.819.23948 REVIEW ARTICLE Launched to Accelerate Biodiversity Research

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 819: 393–396 (2019) Megaloptera of Canada 393 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.819.23948 REVIEW ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Megaloptera of Canada Xingyue Liu1 1 Department of Entomology, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China Corresponding author: Xingyue Liu ([email protected]) Academic editor: D. Langor | Received 29 January 2018 | Accepted 2 March 2018 | Published 24 January 2019 http://zoobank.org/E0BA7FB8-0318-4AC1-8892-C9AE978F90A7 Citation: Liu X (2019) Megaloptera of Canada. In: Langor DW, Sheffield CS (Eds) The Biota of Canada – A Biodiversity Assessment. Part 1: The Terrestrial Arthropods. ZooKeys 819: 393–396.https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.819.23948 Abstract An updated summary on the fauna of Canadian Megaloptera is provided. Currently, 18 species are re- corded in Canada, with six species of Corydalidae and 12 species of Sialidae. This is an increase of two species since 1979. An additional seven species are expected to be discovered in Canada. Barcode Index Numbers are available for ten Canadian species. Keywords alderflies, biodiversity assessment, Biota of Canada, dobsonflies, fishflies, Megaloptera The order Megaloptera (dobsonflies, fishflies, and alderflies) is one of the three orders of Neuropterida, and is characterized by the prognathous adult head, the broad anal area of hind wing and the exclusively aquatic larval stages (New and Theischinger 1993). Currently, there are ca. 380 described species of Megaloptera worldwide (Yang and Liu 2010, Oswald 2016). Extant Megaloptera are composed of only two families; Corydalidae, which is divided into Corydalinae (dobsonflies) and Chauliodinae (fish- flies), and Sialidae (alderflies). -

Oviposition of the Dobsonfly (Corydalus Cornutus, Megaloptera) on a Large River Author(S): Brian P

Am.Midl. Nat. 127:348-354 Oviposition of the Dobsonfly(Corydalus cornutus, Megaloptera) on a Large River BRIAN P. MANGAN EcologyIII, Inc., R.R. 1, Berwick,Pennsylvania 18603 ABSTRACT.-Dobsonflyoviposition and theresults of twoannual surveys of oviposition sitesalong the Susquehanna River, near Berwick, Pennsylvania, in 1985-1986are described. Unlikeother megalopterans, none of the females prepared the substrate before egg deposition. Afterdeposition, females spread a clearfluid over the eggs,which dried to forma hard whitecoating. This coating appeared to protect the eggs from excessive heating and predation. Some4428 eggmasses were observed at 260 sitesin thetwo annual surveys. Trees were themost often used sites, but rocks and deadfallshad higheraverage numbers of egg masses on them.Aggregations of egg masseswere observed in surveyedareas and on individual sites(e.g., 339 on one tree),and Morisita'sDispersion Index showed that egg masses were contagiousin distribution. INTRODUCTION The dobsonflyCorydalus cornutus (L.) is a widely distributedaquatic insectand an im- portantpredator in many lotic ecosystems.Larvae (hellgrammites)are prized as bait for game fishes.Although the insect is well known among anglers,it has receivedrelatively littlescientific attention. Descriptions of the life history,and particularlyoviposition, are sparse and incomplete.Riley (1879) was firstto characterizeoviposition, noting egg masses on objectsoverhanging water. Parfin (1952) studiedpupation, adult emergenceand copu- lationof the insect,and Baker and Neunzig (1968) describedthe egg masses and first-instar larvae. Brown and Fitzpatrick(1978) reportedlife history and populationenergetics of this species. This study investigateddobsonfly oviposition on the Susquehanna River, near Berwick,Pennsylvania, in 1985-1986. My objectiveswere to describedobsonfly oviposition and surveyoviposition sites along a large river.