Chapter 4 the Provincial and Urban Level: Meeting the Local Needs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yamato Transport Branch Postal Code Address TA-Q-BIN Lockers

Yamato Transport Branch Postal Code Address TA-Q-BIN Lockers Location Postal Code Cheers Store Address Opening Hours Headquarters 119936 61 Alexandra Terrace #05-08 Harbour Link Complex Cheers @ AMK Hub 569933 No. 53 Ang Mo Kio Ave 3 #01-37, AMK Hub 24 hours TA-Q-BIN Branch Close on Fri and Sat Night 119937 63 Alexandra Terrace #04-01 Harbour Link Complex Cheers @ CPF Building 068897 79 Robinson Road CPF Building #01-02 (Parcel Collection) from 11pm to 7am TA-Q-BIN Call Centre 119936 61 Alexandra Terrace #05-08 Harbour Link Complex Cheers @ Toa Payoh Lorong 1 310109 Block 109 #01-310 Toa Payoh Lorong 1 24 hours Takashimaya Shopping Centre,391 Orchard Rd, #B2-201/8B Fairpricexpress Satellite Office 238873 Operation Hour: 10.00am - 9.30pm every day 228149 1 Sophia Road #01-18, Peace Centre 24 hours @ Peace Centre (Subject to Takashimaya operating hours) Cheers @ Seng Kang Air Freight Office 819834 7 Airline Rd #01-14/15, Cargo Agent Building E 546673 211 Punggol Road 24 hours ESSO Station Fairpricexpress Sea Freight Office 099447 Blk 511 Kampong Bahru Rd #02-05, Keppel Distripark @ Toa Payoh Lorong 2 ESSO 319640 399 Toa Payoh Lorong 2 24 hours Station Fairpricexpress @ Woodlands Logistics & Warehouse 119937 63 Alexandra Terrace #04-01 Harbour Link Complex 739066 50 Woodlands Avenue 1 24 hours Ave 1 ESSO Station Removal Office 119937 63 Alexandra Terrace #04-01 Harbour Link Complex Cheers @ Concourse Skyline 199600 302 Beach Road #01-01 Concourse Skyline 24 hours Cheers @ 810 Hougang Central 530810 BLK 810 Hougang Central #01-214 24 hours -

Participating Merchants Address Postal Code Club21 3.1 Phillip Lim 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 A|X Armani Exchange

Participating Merchants Address Postal Code Club21 3.1 Phillip Lim 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 A|X Armani Exchange 2 Orchard Turn, B1-03 ION Orchard 238801 391 Orchard Road, #B1-03/04 Ngee Ann City 238872 290 Orchard Rd, 02-13/14-16 Paragon #02-17/19 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, B2-15/16/16A The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 Armani Junior 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-62 018972 Bao Bao Issey Miyake 2 Orchard Turn, ION Orchard #03-24 238801 Bonpoint 583 Orchard Road, #02-11/12/13 Forum The Shopping Mall 238884 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-61 018972 CK Calvin Klein 2 Orchard Turn, 03-09 ION Orchard 238801 290 Orchard Road, 02-33/34 Paragon 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-17A 018972 Club21 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Club21 Men 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Club21 X Play Comme 2 Bayfront Avenue, #B1-68 The Shoppes At Marina Bay Sands 018972 Des Garscons 2 Orchard Turn, #03-10 ION Orchard 238801 Comme Des Garcons 6B Orange Grove Road, Level 1 Como House 258332 Pocket Commes des Garcons 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 DKNY 290 Orchard Rd, 02-43 Paragon 238859 2 Orchard Turn, B1-03 ION Orchard 238801 Dries Van Noten 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Emporio Armani 290 Orchard Road, 01-23/24 Paragon 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-16 The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 Giorgio Armani 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-76/77 The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Issey Miyake 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Marni 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Mulberry 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-41/42 018972 -

13 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

13 bus time schedule & line map 13 Upp East Coast Ter View In Website Mode The 13 bus line (Upp East Coast Ter) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Upp East Coast Ter: 5:35 AM - 11:29 PM (2) Yio Chu Kang Int: 5:30 AM - 11:09 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 13 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 13 bus arriving. Direction: Upp East Coast Ter 13 bus Time Schedule 64 stops Upp East Coast Ter Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:45 AM - 11:29 PM Monday 5:35 AM - 11:29 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 - Yio Chu Kang Int (55509) Tuesday 5:35 AM - 11:29 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Opp Blk 646 (55209) Wednesday 5:35 AM - 11:29 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Bef Ang Mo Kio Lib (54059) Thursday 5:35 AM - 11:29 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Courts Ang Mo Kio (54049) Friday 5:35 AM - 11:29 PM Ang Mo Kio Avenue 6, Singapore Saturday 5:45 AM - 11:29 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Bef Al-Muttaqin Mque (54039) 5140 Ang Mo Kio Avenue 6, Singapore Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Blk 307a (54019) 307A Ang Mo Kio Avenue 1, Singapore 13 bus Info Direction: Upp East Coast Ter Marymount Rd - Blk 254 (53169) Stops: 64 Trip Duration: 99 min Bishan St 22 - Blk 245 (53379) Line Summary: Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 - Yio Chu Kang Int 245 Bishan Street 22, Singapore (55509), Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Opp Blk 646 (55209), Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Bef Ang Mo Kio Lib (54059), Ang Bishan St 22 - Opp Bishan Nth Shop Mall (53389) Mo Kio Ave 6 - Courts Ang Mo Kio (54049), Ang Mo 230 Bishan Street 23, Singapore Kio Ave 6 - Bef Al-Muttaqin Mque (54039), Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Blk 307a (54019), Marymount -

67 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

67 bus time schedule & line map 67 Choa Chu Kang Int View In Website Mode The 67 bus line (Choa Chu Kang Int) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Choa Chu Kang Int: 5:30 AM - 11:30 PM (2) Tampines Int: 5:30 AM - 11:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 67 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 67 bus arriving. Direction: Choa Chu Kang Int 67 bus Time Schedule 83 stops Choa Chu Kang Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:30 AM - 11:30 PM Monday 5:30 AM - 11:30 PM Tampines Ctrl 1 - Tampines Int (75009) 513 Tampines Central 1, Singapore Tuesday 5:30 AM - 11:30 PM Tampines Ave 5 - Opp Our Tampines Hub (76059) Wednesday 5:30 AM - 11:30 PM 5 Tampines Central 6, Singapore Thursday 5:30 AM - 11:30 PM Tampines Ave 5 - Blk 147 (76069) Friday 5:30 AM - 11:30 PM Tampines Ave 1 - Bef Tampines West Stn (75059) Saturday 5:30 AM - 11:30 PM Bedok Reservoir Rd - Bedok Reform Trg Ctr (75069) Bedok Reservoir Rd - the Clearwater Condo 67 bus Info (75349) Direction: Choa Chu Kang Int Bedok Reservoir Road, Singapore Stops: 83 Trip Duration: 116 min Bedok Nth Ave 3 - Bedok Resvr Stn Exit B (84209) Line Summary: Tampines Ctrl 1 - Tampines Int Bedok North Avenue 3, Singapore (75009), Tampines Ave 5 - Opp Our Tampines Hub (76059), Tampines Ave 5 - Blk 147 (76069), Bedok Nth Ave 3 - Blk 109 (84529) Tampines Ave 1 - Bef Tampines West Stn (75059), Bedok Reservoir Rd - Bedok Reform Trg Ctr (75069), Bedok Nth Ave 3 - Bet Blks 139/140 (84219) Bedok Reservoir Rd - the Clearwater Condo (75349), Bedok Nth Ave 3 - -

Biblioasia Jan-Mar 2021.Pdf

Vol. 16 Issue 04 2021 JAN–MAR 10 / The Mystery of Madras Chunam 24 / Remembering Robinsons 30 / Stories From the Stacks 36 / Let There Be Light 42 / A Convict Made Good 48 / The Young Ones A Labour OF Love The Origins of Kueh Lapis p. 4 I think we can all agree that 2020 was a challenging year. Like many people, I’m looking Director’s forward to a much better year ahead. And for those of us with a sweet tooth, what better way to start 2021 than to tuck into PRESERVING THE SOUNDS OF SINGAPORE buttery rich kueh lapis? Christopher Tan’s essay on the origins of this mouth-watering layered Note cake from Indonesia – made of eggs, butter, flour and spices – is a feast for the senses, and very timely too, given the upcoming Lunar New Year. The clacking of a typewriter, the beeping of a pager and the Still on the subject of eggs, you should read Yeo Kang Shua’s examination of Madraschunam , the plaster made from, among other things, egg white and sugar. It is widely believed to have shrill ringing of an analogue telephone – have you heard these been used on the interior walls of St Andrew’s Cathedral. Kang Shua sets the record straight. sounds before? Sounds can paint images in the mind and evoke Given the current predilection for toppling statues of contentious historical figures, poet and playwright Ng Yi-Sheng argues that Raffles has already been knocked off his pedestal – shared memories. figuratively speaking that is. From a familiar historical figure, we turn to a relatively unknown personality – Kunnuck Mistree, a former Indian convict who remade himself into a successful and respectable member of society. -

541 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

541 bus time schedule & line map 541 [AM]: Shenton Way (Opp MAS Bldg) [PM]: View In Website Mode Bayshore Rd (Outside The Bayshore) The 541 bus line ([AM]: Shenton Way (Opp MAS Bldg) [PM]: Bayshore Rd (Outside The Bayshore)) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bayshore Rd (Outside the Bayshore): 5:15 PM - 8:05 PM (2) Shenton Way (Opp Mas Bldg): 7:09 AM - 9:09 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 541 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 541 bus arriving. Direction: Bayshore Rd (Outside the Bayshore) 541 bus Time Schedule 20 stops Bayshore Rd (Outside the Bayshore) Route VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Timetable: Sunday Not Operational Anson Rd - Hub Synergy Pt (03222) Monday 5:15 PM - 8:05 PM 70 Anson Road, Singapore Tuesday 5:15 PM - 8:05 PM Anson Rd - Tanjong Pagar Stn Exit C (03223) 10 Anson Road, Singapore Wednesday 5:15 PM - 8:05 PM Robinson Rd - Aft Capital Twr (03111) Thursday 5:15 PM - 8:05 PM 01-05, Capital Tower Friday 5:15 PM - 8:05 PM Robinson Rd - Opp So Soƒtel S'Pore (03071) Saturday Not Operational Robinson Road, Singapore Robinson Rd - Ra«es Pl Stn Exit F (03031) 1 Robinson Road, Singapore 541 bus Info Fullerton Rd - Fullerton Sq (03011) Direction: Bayshore Rd (Outside the Bayshore) Stops: 20 Nicoll Highway - Opp Suntec City (80151) Trip Duration: 44 min Line Summary: Anson Rd - Hub Synergy Pt (03222), Nicoll Highway - Opp Nicoll Highway Stn (80161) Anson Rd - Tanjong Pagar Stn Exit C (03223), Robinson Rd - Aft Capital Twr (03111), Robinson Rd - Amber Rd - Opp Amber Gdn (92249) Opp So -

NEW PARALLEL BUS SERVICE 951E from 17 JUNE - Service Connects Woodlands Residents to and from the City

Jun 11, 2013 16:00 +08 NEW PARALLEL BUS SERVICE 951E FROM 17 JUNE - Service connects Woodlands residents to and from the city A new SMRT parallel bus service – Service 951E – that connects the Woodlands neighbourhoods to the Central Business District (CBD) will begin operations from Monday, 17 June 2013. This is the 12th bus service to be rolled out under the Land Transport Authority’s Bus Service Enhancement Programme (BSEP). The new service will provide greater connectivity and an alternative travel option for Woodlands residents travelling to and from areas in the CBD during weekday morning and evening peak-hours (excluding public holidays). Parallel Service 951E will operate two one-way trips on weekday mornings at 7.30 am and 7.45 am from Woodlands Street 82, Woodlands Avenue 4 and Woodlands Avenue 1 to areas within the CBD such as Orchard Road, Bras Basah Road, Nicoll Highway, Collyer Quay, Raffles Quay and Shenton Way. On weekday evenings, two one-way trips at 6.15 pm and 6.30 pm will connect commuters from areas such as Anson Road, Collyer Quay, Fullerton Road, Esplanade Drive, Stamford Road, Orchard Road and Penang Road to the Woodlands neighbourhoods. Please refer to the attached poster for more details. Vice President for SMRT Buses Ltd, Tan Kian Heong said: "We are pleased to have the opportunity to operate yet another new parallel bus service that directly connects the heartlands and the city. Utilising the Central Expressway (CTE), Seletar Expressway (SLE) and with less bus stops along its route, this parallel bus service enhances the overall travelling experience of our customers by offering them not only more convenience when commuting to and from the CBD, but also presents them an alternative travel option on top of other bus services and the MRT." Passengers may contact SMRT Customer Relations Centre at 1800-336-8900 from 7.30am to 6.30pm on weekdays (excluding public holidays) or visit www.smrt.com.sg for more information on Service 951E. -

Reference Projects for ROCKINSUL in Singapore

Reference Projects for ROCKINSUL in Singapore 1C Sakra Ave ( Evonik @ Jurong Island ) Apple HQ At Ang Mo Kio Hub - GALILEO Project Asia Square Tower @ Marina Bay ASME Technology Auditorium @ SP (Gate 8) Beatty Secondary School @ No.1 Toa Payoh North Bendemeer Primary School Boon Lay Community Centre Bukit Panjang N5C13 Canberra & Yio Chu Kang Primary School Centra Place @ 1 Hougang St.1 Changi Prison Complex Chinatown Point Dazhong Primary School @ Bukit Batok DBS Showflat Downtown Line Project East Spring Primary School@ Tampines GLYNOEBROURNE Hamilton Scotts @ Orchard Road ITE Central Ang Mo Kio Lengkok Mariam 2 Light Industrial @ Lavendar St Marina Bay Financial Centre Tower 3 (MBFC Tower 3) Miri Malaysia Project MOM Building @ Bendemeer Road Mural Camp Upgrading Nanyang Poly Technic Nissim Hill Condo No.151 bencoleen st ( NAFA CAMPUS 3 4th STOREY ) NTU Hall of Residence NUS Block MD6 www.rockwoolindia.com Reference Projects for ROCKINSUL in Singapore One North @ 3 Fusiono Polis Link Pacnet Project , Paya Lebar River Safari Mandai Zoo Roche - Tuas Bay Link SAF Armour Centre Samsung GMR Energy Project - Jurong Island Scanning Station @ Brani Terminal Ave Scare Hotel @ Chin Swee Road Schenker Schenker Building @ Changi School at Woodlands Crescent Seacare Hotel @ Chin Swee Road Seletar Hanger Project Sengkang Primary School Sg Poly ( Blk ) 1 @ Dover Road Singapore American School Singapore Polytechnic Block 1 SIP Denki Project Space @ Kovan SUTD Campus @ Changi Tampines Substation Tan Tock Seng Hospital Tannery @ Choa Chu Kang Road Temp Holding Building @ NTU The Heeren The Signature Building @ Changi Business Park TUAS DEPOT C1685 Tuas Mega Shipyard Tuas Naval Base Tuas South Boulevard Mega Yard Store Tuas West C1685 UPS Hotel @ Upper Pickering Street (Park Royal Hotel) Westgate @ Jurong East Yio Chu Kang Primary School Yishun Polyclinic Yishun Ring Road (Lup G98) Blk 326 www.rockwoolindia.com Reference Projects for ROCKINSUL in Singapore 1 Marina Boulevard (NTUC Centre) 211 Temp Sports Facility @ Sin Ming ave 25 International Business Park. -

View in Website Mode

70 bus time schedule & line map 70 Shenton Way Ter View In Website Mode The 70 bus line (Shenton Way Ter) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Shenton Way Ter: 5:30 AM - 5:54 PM (2) Yio Chu Kang Int: 5:45 AM - 7:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 70 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 70 bus arriving. Direction: Shenton Way Ter 70 bus Time Schedule 55 stops Shenton Way Ter Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 5:30 AM - 5:54 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 - Yio Chu Kang Int (55509) Tuesday 5:30 AM - 5:54 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 9 - Amk Police Div Hq (55301) Ang Mo Kio Avenue 9, Singapore Wednesday 5:30 AM - 5:54 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 9 - Opp Yio Chu Kang Stadium Thursday 5:30 AM - 5:54 PM (55311) Friday 5:30 AM - 5:54 PM 2 Ang Mo Kio Street 62, Singapore Saturday 5:35 AM - 5:54 PM Ang Mo Kio St 63 - Sbst Ang Mo Kio Depot (55239) 19 Ang Mo Kio Street 63, Singapore Ang Mo Kio St 64 - Smrt Buses Amk Depot 70 bus Info (55229) Direction: Shenton Way Ter 6 Ang Mo Kio Street 62, Singapore Stops: 55 Trip Duration: 94 min Yio Chu Kang Rd - Opp Ue Bizhub Ctrl (55041) Line Summary: Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 - Yio Chu Kang Int (55509), Ang Mo Kio Ave 9 - Amk Police Div Hq Yio Chu Kang Rd - Opp St Electronics (55051) (55301), Ang Mo Kio Ave 9 - Opp Yio Chu Kang Yio Chu Kang Road, Singapore Stadium (55311), Ang Mo Kio St 63 - Sbst Ang Mo Kio Depot (55239), Ang Mo Kio St 64 - Smrt Buses Yio Chu Kang Rd - Bef Econ Medicare Ctr (55071) Amk Depot (55229), Yio Chu Kang Rd - Opp Ue Bizhub Ctrl (55041), Yio -

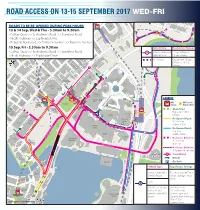

LTA F1 2017 Maps

GOLDEN MILE ROAD ACCESS ON 13-15 SEPTEMBER 2017 WED-FRI TOWER BEACH ROAD CONCOURSE PARKROYAL ON NAFA SHOPPING MALL CAMPUS 1 C PARKVIEW BEACH ROAD SQUARE BUGIS + OPHIR ROAD ROADS TO BE REOPENED DURING PEAK HOURS BUGIS NICOLL HIGHWAY CONCOURSE A SKYLINE 13 & 14 Sep, Wed & Thu • 5.30am to 9.30am NICOLL HIGHWAY NAFA CAMPUS 2 BUGIS B REPUBLIC AVENUE A JUNCTION THE PLAZA • Collyer Quay >> St Andrew's Road >> Stamford Road D NATIONAL DESIGN CTR • Nicoll Highway >> Esplanade Drive B BEACH ROAD • Republic BoulevardD E >> Temasek Avenue >> Bayfront Avenue NICOLL HIGHWAY THE SINGAPORE GATEWAY Vehicle Type: Road Access Timings: ART MUSEUM OPHIR ROAD VICTORIA STREET ROCHOR ROAD 15 Sep, FriC • 5.30am to 9.30am NATIONAL QUEEN STREET LIBRARY Vehicles With Valid 15 Sep 9.30am to BUILDING • Collyer Quay >> St AAndrew's Road >> Stamford Road SMU Vehicle Passes 18 Sep 5.30am BRAS BASAH • Nicoll Highway >> Esplanade Drive MIDDLE ROAD All Vehicles Closed from 15 Sep BRAS BASAH B COMPLEX BEACH ROAD 9.30am to 18 Sep PURVIS STREET SHAW 5.30am CARLTON TOWERS HOTEL MIDDLE ROAD SEAH STREET NICOLL HIGHWAY CHIJMES SOUTH BRAS BASAH ROAD BEACH TOWER SUNTEC SUNTEC TOWER 2 RAFFLES HOTEL TOWER 1 STAMFORD ROAD SHOPPING ARCADE SOUTH SUNTEC BEACH TOWER 3 OPHIR ROAD OPHIR NORTH BRIDGE ROAD RAFFLES HILL STREET SOUTH FOUNTAIN ARMENIAN BEACH SUNTEC OF WEALTH CHURCH CITY FAIRMONT RESIDENCES TOWER 5 SUNTEC TOWER 4 F SUNTEC INTL ROAD ROCHOR CONVENTION & SWISSOTEL THE CAPITOL B A STAMFORD G EXHIBITION CTR PIAZZA C C LEGEND REPUBLIC BOULEVARD GRAND PARK SUNTEC E A B CITYHALL CITY -

Download Project Reference

PPI ENGINEERING PTE LTD PPI ENGINEERING SYSTEMS PTE LTD 42 Pioneer Sector 2 Singapore 628393 Tel: 68989095 Fax: 68989785 Website: www.ppi.sg Email: [email protected] Date : Nov-16 JOB REFERENCES ON-GOING PROJECTS Year Projects Description Scopes Main Contractor/Client Consultants Owner 2016 GKE Warehouse at 39 Benoi Road Post-tensioning Works - Beams + Flat Slab HPC Builders Pte Ltd CS Engineers Consulting GKE 2016 Fernvale School Post-tensioning Works - Beams Zheng Keng Engineering & Const. PL Sembcorp AE MOE 2016 OVH at Sentosa Post-tensioning Works - Beams + Slab Woh Hup Construction Pte Ltd KCL Consultants P/L Private 2016 IDS at 279 Jalan Ahmad Ibrahim Post-tensioning Works - Beams + Flat Slab Hua Siah Construction KTP Private 2016 Factory at 10 Changi Sth St 2 Post-tensioning Works - Beams + Flat Slab Lida Construction Tenwit Consultant Private 2016 ER382 - Lornie Road Upgrading Post-tensioning Works - PSPC Beams Coninco TYLin LTA 2016 Ice Cave at Yung Ho Rd Post-tensioning Works - Flat Slab Hua Siah Construction Ronnie & Koh Private 2016 MRF Factory @ 7 Tuas South St 7 Post-tensioning Works - Flat Slab Buildform Milleniums Consultamt Private 2016 Warehouse at Plot 6 Tampines Drive Post-tensioning Works - Flat Slab Lim Wen heng Const. KCL Consultants P/L Private 2016 Shine at Tuas South Ave 7 Post-tensioning Works - Beams + Flat Slab Hock Liang Seng EP Engineers Hock Liang Seng 2016 ER397 - TPE/KPE Upgrading Post-tensioning Works - PSPC Beams Coninco TYLin LTA 2016 ER343 - Portsdown Rd Post-tensioning Works - PSPC Beams Coninco TYLin -

Policy Guidelines for Road Transport Pricing

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC POLICY GUIDELINES FOR ROAD TRANSPORT PRICING A Practical Step-by-Step Approach UNITED NATIONS Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific & Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH POLICY GUIDELINES FOR ROAD TRANSPORT PRICING A Practical Step-by-Step Approach Edited by: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH, Germany; and the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) Financed by: Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (BMZ), Germany Authors: Jan A. Schwaab and Sascha Thielmann United Nations New York, 2002 ST/ESCAP/2216 Edited by: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH Manfred Breithaupt; Division 44, Environmental Management, Water, Energy and Transport; Dag-Hammarskjöld-Weg 1-5, 65760 Eschborn, Germany Tel.: +49 (0) 6196 / 79 – 1267, Fax: +49 (0) 6196 / 79 - 7144 WWW: http://www.gtz.de United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) Transport and Tourism Division The United Nations Building, Rajadamnern Nok Avenue, Bangkok 10200, Thailand Tel.: +66-2 / 288-1234, Fax: +66-2 / 288-1000, 288-3050 WWW: http://www.unescap.org/tctd/ Financed by: Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (BMZ) Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 40, 53113 Bonn, Germany Tel.: +49 (0) 228 / 535 – 0, Fax: +49 (0) 228 / 535 - 3500 WWW: http://www.bmz.de Authors: Jan A. Schwaab and Sascha Thielmann The authors wish to express their gratitude for the many constructive and helpful comments provided by Manfred Breithaupt, Karl Fjellstrom, Axel Friedrich, Gerhard Metschies, Martine Micozzi, Dieter Niemann, Anthony Ockwell and Werner Rothengatter.