Fragmented Lens of War a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts at George Mason University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Legion

112th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 112–86 PROCEEDINGS OF 93 rd NATIONAL CONVENTION of the AMERICAN LEGION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 26–September 1, 2011 VerDate Mar 15 2010 01:46 Feb 16, 2012 Jkt 072732 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5009 Sfmt 5009 E:\HR\OC\HD086P1.XXX HD086P1 rfrederick on DSK6VPTVN1PROD with HEARING E:\SEALS\AMLEG.eps 2011 : 93rd NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE AMERICAN LEGION : 2011 VerDate Mar 15 2010 01:46 Feb 16, 2012 Jkt 072732 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 E:\HR\OC\HD086P1.XXX HD086P1 rfrederick on DSK6VPTVN1PROD with HEARING with DSK6VPTVN1PROD on rfrederick 1 112th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 112–86 PROCEEDINGS OF THE 93RD NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE AMERICAN LEGION COMMUNICATION FROM THE DIRECTOR, NATIONAL LEGISLATIVE COMMISSION, THE AMERICAN LEGION TRANSMITTING THE FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND INDEPENDENT AUDIT OF THE AMERICAN LEGION, PROCEEDINGS OF THE 93RD ANNUAL NA- TIONAL CONVENTION OF THE AMERICAN LEGION, HELD IN MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA FROM AUGUST 26–SEPTEMBER 1, 2011, AND A REPORT ON THE ORGANIZATION’S ACTIVITIES FOR THE YEAR PRECEDING THE CONVENTION, PURSUANT TO 36 U.S.C. 49 FEBRUARY 7, 2012.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 72–732 WASHINGTON : 2012 VerDate Mar 15 2010 01:46 Feb 16, 2012 Jkt 072732 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HD086P1.XXX HD086P1 rfrederick on DSK6VPTVN1PROD with HEARING E:\Seals\Congress.#13 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL THE AMERICAN LEGION, Washington, DC, January 27, 2012. Hon. JOHN BOEHNER, Speaker, House of Representatives, Washington, DC. -

![The American Legion Magazine [Volume 104, No. 2 (February 1978)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7715/the-american-legion-magazine-volume-104-no-2-february-1978-2417715.webp)

The American Legion Magazine [Volume 104, No. 2 (February 1978)]

! 100% man-made shoes HABAND of Paterson HABAND NEVER HOLLER ^5 LAST CHANCE Manufacturers have already announced such huge increases that our incredible 2 for $19.95 price is impossible to continue! So before this famous offer is gone forever, please take advantage of this one FINAL SALE! ook at these shoes. You will see . all these styles in the posh $45 shoe showrooms. But you would be startled to know how many important men are wearing our Haband shoes instead! They buy 2 pair for 19.95 ! Why should you Overspend Your Hard-Earned Money ? Nobody will know the difference — not even your feet! All our shoes are made in the U.S.A. by one of America's most famous shoe factories on excellent hand- carved lasts, & you will be amazed at the comfort! Now while this last-chance low price still exists, get the famous Haband TRIPLE PLUS : Longer Life than we dare promise out loud I Exact Fit —All sizes in stock. and \ Soft zipper Side PLEASE RUSH! As soon as existing stocks are sold out, this offer will be immediately discontinued. Too These are the famous 100% polymeric Executive Club dress shoes made with life-of-the-shoe PVC sole and heel, flexible support shank in the arch, wheeled edge soles, heavy metal buckles and trim. Even a built-in split leather sock lining next to your foot. All these shoes are the newest styles, copied from $35 to $50 originals. At 2 pairs for $19.95 you save big money! And read our GUARANTEE You Deal Direct! Just r~aband's 100% man-made use the coupon at right. -

Website Listing Ajax

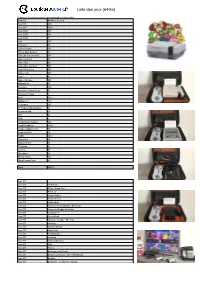

Liste des jeux (64Go) Cliquez sur le nom des consoles pour descendre au bon endroit Console Nombre de jeux Atari ST 274 Atari 800 5627 Atari 2600 457 Atari 5200 101 Atari 7800 51 C64 150 Channel F 34 Coleco Vision 151 Family Disk System 43 FBA Libretro (arcade) 647 Game & watch 58 Game Boy 621 Game Boy Advance 951 Game Boy Color 501 Game gear 277 Lynx 84 Mame (arcade) 808 Nintento 64 78 Neo-Geo 152 Neo-Geo Pocket Color 81 Neo-Geo Pocket 9 NES 1812 Odyssey 2 125 Pc Engine 291 Pc Engine Supergraphx 97 Pokémon Mini 26 PS1 54 PSP 2 Sega Master System 288 Sega Megadrive 1030 Sega megadrive 32x 30 Sega sg-1000 59 SNES 1461 Stellaview 66 Sufami Turbo 15 Thomson 82 Vectrex 75 Virtualboy 24 Wonderswan 102 WonderswanColor 83 Total 16877 Atari ST Atari ST 10th Frame Atari ST 500cc Grand Prix Atari ST 5th Gear Atari ST Action Fighter Atari ST Action Service Atari ST Addictaball Atari ST Advanced Fruit Machine Simulator Atari ST Advanced Rugby Simulator Atari ST Afterburner Atari ST Alien World Atari ST Alternate Reality - The City Atari ST Anarchy Atari ST Another World Atari ST Apprentice Atari ST Archipelagos Atari ST Arcticfox Atari ST Artificial Dreams Atari ST Atax Atari ST Atomix Atari ST Backgammon Royale Atari ST Balance of Power - The 1990 Edition Atari ST Ballistix Atari ST Barbarian : Le Guerrier Absolu Atari ST Battle Chess Atari ST Battle Probe Atari ST Battlehawks 1942 Atari ST Beach Volley Atari ST Beastlord Atari ST Beyond the Ice Palace Atari ST Black Tiger Atari ST Blasteroids Atari ST Blazing Thunder Atari ST Blood Money Atari ST BMX Simulator Atari ST Bob Winner Atari ST Bomb Jack Atari ST Bumpy Atari ST Burger Man Atari ST Captain Fizz Meets the Blaster-Trons Atari ST Carrier Command Atari ST Cartoon Capers Atari ST Catch 23 Atari ST Championship Baseball Atari ST Championship Cricket Atari ST Championship Wrestling Atari ST Chase H.Q. -

American Culture and Submarine Warfare in the Twentieth Century

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2011 Beneath the Surface: American Culture and Submarine Warfare in the Twentieth Century Matthew Robert McGrew University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Cultural History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McGrew, Matthew Robert, "Beneath the Surface: American Culture and Submarine Warfare in the Twentieth Century" (2011). Master's Theses. 209. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/209 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi BENEATH THE SURFACE: AMERICAN CULTURE AND SUBMARINE WARFARE IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Matthew Robert McGrew A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved: Andrew A. Wiest ____________________________________ Director Andrew P. Haley ____________________________________ Michael S. Neiberg ____________________________________ Susan A. Siltanen ____________________________________ Dean of the Graduate School August 2011 ABSTRACT BENEATH THE SURFACE: AMERICAN CULTURE AND SUBMARINE WARFARE IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Matthew Robert McGrew August 2011 Cultural perceptions guided the American use of submarines during the twentieth century. Feared as an evil weapon during the First World War, guarded as a dirty secret during the Second World War, and heralded as the weapon of democracy during the Cold War, the American submarine story reveals the overwhelming influence of civilian culture over martial practices. -

Mari-Timesmari-Times Volume 22, Issue 2 Summer, 2014

MARI-TIMESMARI-TIMES VOLUME 22, ISSUE 2 SUMMER, 2014 & LIGHTHOUSE PRESERVATION SOCIETY Contents View from the Wheelhouse Director's Report ...........................page 2 Mission/Vision Statements...............page 3 Museum Hours .....................................page 3 Volunteer Corner .................................page 4 Development Director's Report .....page 5 New Crew Members ...........................page 6 Crossing the Bar ...................................page 6 DCMM News ..........................................page 7 Boat Building Class Project ..............page 7 Pirates at Work and Play Mission of the Coast Guard ..............page 7 By June Larson Volunteer Spotlight ............................page 8 Golden Heart Nomination................page 9 irates were young, physically fit men (oh, there were a few women too). Climbing Event Review ..............................page 10 - 11 ropes and trimming sails took a lot of energy. Fighting with pistols and swords required good muscle and strength. Many fled the military discipline life of a Nautical Trivia..................................... page 14 P European navy to have more freedom. Men aboard pirate ships often voted on who was to Nautical Nitche .................................. page 16 be the captain, when to raid ships, and how booty and treasures were to be divided after New Business Partners ................... page 17 the capture of merchant ships. Many thought it was a "get rich quick occupation." On most pirate ships there were 80-150 men. Each man had an assignment while on Our Wish List ...................................... page 17 board. Many of the crew chose to be pirates, but others were captured during raids of Honorariums and Memorials ....... page 17 ships or villages on shore and forced to join the crew. Walk of Fame Bricks ......................... page 17 The captian was often elected by the crew. Privateer captains were granted declarations Gifts In-Kind ....................................... -

American Jewish History Month

American Jewish History Month This weekend is the last weekend in the month of May, meaning that this Monday is Memorial Day, a time for all Americans to pause to reflect upon our freedoms. It is a day set aside to mourn the loss and express gratitude for those individuals who gave the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of our nation. We recall and honor those who have died in our nation’s wars and who gave their lives for a greater good. All too often, amidst the barbecues, sales, launch of summer, and the long holiday weekend we forget, neglect or overlook why we have Monday off. I would like to suggest that at some point, and perhaps right now, while we are in Shabbat services may be as good a time as any, we should acknowledge the meaning of this day, and we should be conscious of its meaning and significance. The last weekend in the month of May also coincides with another notable commemoration, as this is the second annual American Jewish History month. I want to share a story which captures the essence of both Memorial Day, and American Jewish history, which recalls the contributions we have made to this country. In January of 1943 a crowded 18 year old coastal steamer converted to a troop transport, carrying more than 900 soldiers and civilian workers set out for a new army command base in Greenland. The Dorchester sailed north from New York to Saint John's, Newfoundland, where it joined three U.S. Coast Guard cutters to form a convoy. -

Across 4. Axis Powers. Noun. a Group of Countries That Opposed the Allied

Name: _____________________________________ Date: _______ Period: _______ ww2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Across 10. is a cultural icon of the United States, 2. A war bond consists of debt securities 4. Axis powers. noun. a group of countries representing the American women who issued by a government for the purpose of that opposed the Allied powers in World War II, worked in factories and shipyards during World financing military operations during times of including Germany, Italy, and Japan as well as War II, war. Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Yugoslavia. The Axis powers were led by Nazi Germany. 11. Pearl Harbor definition. A major United 3. Internment means putting a person in States naval base in Hawaii that was attacked prison or other kind of detention, generally in 7. this is a Program with a series of laws without warning by the Japanese air force on wartime. During World War II, the American and diplomatic agreements, initiated on December 7, 1941, with great loss of American government put Japanese-Americans in August 4, 1942, lives and ships. internment camps, fearing they might be loyal to Japan. 8. The victorious allied nations of World War 12. a fixed allowance of provisions or food, I and World War II. In World War I, the Allies especially for soldiers or sailors or for civilians 5. The Torpedo Alley, or Torpedo Junction, included Britain, France, Italy, Russia, and the during a shortage: a daily ration of meat and off North Carolina, is one of the graveyards of United States. -

PROCEEDINGS of the 93 Annual National Convention of the AMERICAN LEGION

DIGEST OF MINUTES OF NATIONAL CONVENTION—AUGUST MINUTES NATIONAL OF OF DIGEST 1, SEPTEMBER 30-31, 2011 352&((',1*6 RIWKH UG$QQXDO1DWLRQDO&RQYHQWLRQ RI 7+($0(5,&$1/(*,21 0LQQHDSROLV&RQYHQWLRQ&HQWHU 0LQQHDSROLV0LQQHVRWD $XJXVW6HSWHPEHU 3ULQWHGLQ86$ ZZZOHJLRQRUJ 6WRFN1R ',675,%87,21 HD7R1(& $OW1(& 3DVW1DWLRQDO&RPPDQGHUV 1DWLRQDO2IILFHUV )LQDQFH&RPPLVVLRQ &RPPLVVLRQ &RPPLWWHH&KDLUPHQ HD7R)RUHLJQ'HSDUWPHQWV 2SWLRQDO'HSDUWPHQWV PROCEEDINGS of the 93rd Annual National Convention of THE AMERICAN LEGION Minneapolis Convention Center Minneapolis, Minnesota August 30 - September 1, 2011 Table of Contents Tuesday, August 30, 2011 Call to Order: National Commander Foster ....................................................................... 1 Invocation .......................................................................................................................... 1 Pledge of Allegiance .......................................................................................................... 1 POW/MIA Empty Chair Ceremony .................................................................................. 2 Preamble to The American Legion Constitution ............................................................... 2 Post Everlasting Ceremony................................................................................................ 2 Convention Opening .......................................................................................................... 2 The American Legion Youth Champions: 2010 Baseball -

Full Book PDF Download

TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page i The naval war film TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page ii TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page iii The naval war film GENRE, HISTORY, NATIONAL CINEMA Jonathan Rayner Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page iv Copyright © Jonathan Rayner 2007 The right of Jonathan Rayner to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 7098 8 hardback EAN 978 0 7190 7098 3 First published 2007 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in 10.5/12.5pt Sabon by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong Printed in Great Britain by CPI, Bath TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page v For Sarah, who after fourteen years knows a pagoda mast when she sees one, and for Jake and Sam, who have Hearts of Oak but haven’t got to grips with Spanish Ladies. -

A Study of Einstürzende Neubauten

This work has been submitted to ChesterRep – the University of Chester’s online research repository http://chesterrep.openrepository.com Author(s): Jennifer Shryane Title: Evading do-re-mi: Destruction and utopia: A study of Einstürzende Neubauten Date: 2009 Originally published as: University of Liverpool PhD thesis Example citation: Shryane, J. (2009). Evading do-re-mi: Destruction and utopia: A study of Einstürzende Neubauten. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Liverpool, United Kingdom. Version of item: Submitted version Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10034/118073 Evading do-re-mi Destruction and Utopia A Study of Einstürzende Neubauten JENNIFER SHRYANE PhD Performing Arts University of Liverpool 2009 Evading do-re-mi Destruction and Utopia We hungered for music almost seething beyond control-or even something beyond music, a violent feeling of soaring unstoppably, powered by immense angular machinery across abrupt and torrential seas of pounding blood (Tony Conrad, Inside the Dream Syndicate, 1965,Table of Element, 2000). London, 04.05 & Grundstück symbol, 11.04 (Photographs taken and overlaid for author by K. Shryane) A Study of Einstürzende Neubauten Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jennifer Shryane, October, 2009. 2 CONTENT Part One: Context for Destruction The philosophical, historical and cultural background for Einstürzende Neubauten as Nachgeborenen and ‘Destructive Characters’. Prologue Löcher und Loss: writing about performance – three gigs. Chapter One Architecture, Angels and Utopia: the artists-thinkers whose ideas and practice have influenced, stimulated and informed Einstürzende Neubauten’s work. Chapter Two Kattrins Trommel: Germany’s Sonderweg/special way with music and its influence on Einstürzende Neubauten. -

SPRING SALE Clear Tonight; Nomas

2« - MANCHESTER HERALD, Wed., April 7, 1982 Motorcjrctot'Sfcirclaa 64 1960 HONDA 750-F-Suptiper Sport. E^xcellentellent condition. Satellite MANCHESTER LUMBER Extras. TelephonePeleph 646- Weather, job action 0811, or 647-0^ anytime. SCHWINN BMX SX 100 - Good condition. Many alloy combine to shut MCC parts. W o rth 'll; will sell keeps tabs for 6250. Negotiable. Ready to race. Mixe, 649-8^. ... page 3 MOTORCYCLE INSURANCE - Lowest Rates Available! Many op on forests tions. Call: Clarice or Joan, Clarice Insurance Agency 643-1126. By LeRoy Pope area of the Atlantic. Campers-rrafters-Mobfto UPl Business Writer Satellite mapping and SPRING SALE Clear tonight; Nomas . 65 Manchester, Conn. NEW YORK - Satellite monitoring is widely used mapping has given a bit of also for spreading flood cloudy Friday Thursday, April 8, 1982 ACE TRAILER -18 Ft. 1972 and forest fire alarms in Self-contained. Sleeps six. new meaning to the old gag many parts of the world, Sale Ends Saturday April 10 — all prices cash & carry Asking $1800 or best offer. about not being able to see — See page 2 Single copy 25(( Telephone 646-8090 after 5 and for making detailed the forest for the trees. maps, that will serve as '2 OFF p.m. or weekends. Scientists have dis covered i t ’s easier to guides for the best use of detect disease in forest land resources. Protect Your Home LEGAL NOTICE For St. Regis and other NOTICE OK trees from a satellite 440 miles up in the skies then corporate and government ith A New R oof® RECEIPT OF users, the most difficult DESIGN APPROVAL by walking among the trees on the ground. -

The Propeller

THE PROPELLER The propeller hangs from the air bag that lifted it off the bottom. Compiled By: Dan Jensen Based on information supplied by: Aruba Esso News Ray H. Burson Dr. Lee A. Dew Don Gray Dufi Kock Lago Colony web site Bill Moyer Stanley Norcom & THE DIVE TEAM IN ARUBA All the proceeds from the sale of this book will be donated to the SS Oranjestad Memorial Committee, which is overseeing the construction of a monument in Aruba. This monument will incorporate the propeller taken from the lake tanker SS Esso Oranjestad and is to be dedicated to those civilians who lived and worked in Aruba and were connected with the production of vital gasoline needed for the war effort or the defense of the island and lost their lives as a result of enemy action during World War II. It is hoped that with this monument, those people and the tragedy of war will be remembered. i COPYRIGHT 2009, SS ORANJESTAD MEMORIAL COMMITTEE, ARUBA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ISBN 978-0-615-31060-2 Second Printing November 2009 500 copies ii The Dive Team The Dive Team in Aruba that retrieved the propeller consists of the following persons: Percy Sweetnam, Team Leader Dick de Bruin Rigo Hoencamp Toine van der Klooster Andre Loonstra Paulus Martijn Special Thanks Special thanks to the following persons: Dufi Kock, for his help before and throughout this book, as well as his efforts toward a monument; Lad Mingus for suggestions; Toni Wilkinson for much needed editing; my dear wife Mary B. (BeBe); the helpful people at Lloyds in London; Anne Cowne, Jean Moreno and Kevin Norster for help with research on the SS Esso Oranjestad and the propeller’s Lloyds Test stamp; my son Paul Jensen, for doing the cover design and my daughter Lise Bessant for reading over the manuscript before printing.