Morocco Western Sahara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Eric James Schmidt 2018 © Copyright by Eric James Schmidt 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger by Eric James Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Timothy D. Taylor, Chair This dissertation examines how Tuareg people in Niger use music to reckon with their increasing but incomplete entanglement in global neoliberal capitalism. I argue that a variety of social actors—Tuareg musicians, fans, festival organizers, and government officials, as well as music producers from Europe and North America—have come to regard Tuareg music as a resource by which to realize economic, political, and other social ambitions. Such treatment of culture-as-resource is intimately linked to the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism, which has led individual and collective subjects around the world to take on a more entrepreneurial nature by exploiting representations of their identities for a variety of ends. While Tuareg collective identity has strongly been tied to an economy of pastoralism and caravan trade, the contemporary moment demands a reimagining of what it means to be, and to survive as, Tuareg. Since the 1970s, cycles of drought, entrenched poverty, and periodic conflicts have pushed more and more Tuaregs to pursue wage labor in cities across northwestern Africa or to work as trans- ii Saharan smugglers; meanwhile, tourism expanded from the 1980s into one of the region’s biggest industries by drawing on pastoralist skills while capitalizing on strategic essentialisms of Tuareg culture and identity. -

Periodic Report of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic

PERIODIC REPORT OF THE SAHRAWI ARAB DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC TO THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES RIGHTS CONTAINING ALL THE OUTSTANDING REPORTS IN ACCORDANCE WITH ARTICLE 62 OF THE CHARTER October 2011 i Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Part I: Data on the General Framework for the Promotion of Human Rights in the Sahrawi Republic in Accordance with the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights ........................... 7 Chapter One: General Information About the Sahrawi Republic ....................................................... 7 i) The Region ...................................................................................................................................... 7 ii) Population ........................................................................................................................................ 7 iii) Language ..................................................................................................................................... 7 iv) Economy ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter Two: The Process of Democratization in Western Sahara ................................................. 8 Chapter Three: The Legal and Institutional Framework for the Promotion of Human Rights in the Sahrawi Republic .............................................................................................................................. -

Sahrawi Women in the Liberation Struggle of the Sahrawi People Author(S): Anne Lippert Source: Signs, Vol

Sahrawi Women in the Liberation Struggle of the Sahrawi People Author(s): Anne Lippert Source: Signs, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Spring, 1992), pp. 636-651 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174626 Accessed: 18/05/2010 18:01 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs. http://www.jstor.org REVISIONS / REPORTS SahrawiWomen in the Liberation Struggle of the SahrawiPeople Anne Lippert Introduction - T H R O U G H T H E I R R O LE S in the currentliberation strug- gle of the Sahrawisof WesternSahara, Sahrawi women have substantiallyincreased their traditionalparticipation and im- portance in that society. -

Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps

Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-420-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org December 2008 1-56432-420-6 Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Map Of North Africa ....................................................................................................... 1 Summary...................................................................................................................... 2 Western Sahara ....................................................................................................... 3 Refugee Camps near Tindouf, Algeria ...................................................................... 8 Recommendations ...................................................................................................... 12 To the UN Security Council ..................................................................................... 12 Recommendations to the Government of Morocco .................................................. 12 Recommendations Regarding Human Rights in the Tindouf Camps ........................ -

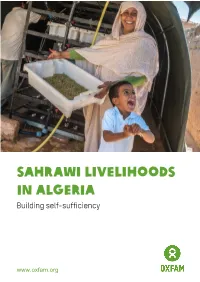

Sahrawi Livelihoods in Algeria: Building Self

Sahrawi livelihoods in algeria Building self-sufficiency www.oxfam.org OXFAM CASE STUDY – SEPTEMBER 2018 Over 40 years ago, Oxfam began working with Sahrawi refugees living in extremely harsh conditions in camps in the Saharan desert of western Algeria, who had fled their homes as a result of ongoing disputes over territory in Western Sahara. Since then, the Sahrawi refugees have been largely dependent on humanitarian aid from a number of agencies, but increasing needs and an uncertain funding future have meant that the agencies are having to adapt their programme approaches. Oxfam has met these new challenges by combining the existing aid with new resilience-building activities, supporting the community to lead self-sufficient and fulfilling lives in the arid desert environment. © Oxfam International September 2018 This case study was written by Mohamed Ouchene and Philippe Massebiau. Oxfam acknowledges the assistance of Meryem Benbrahim; the country programme and support teams; Eleanor Parker; Jude Powell; and Shekhar Anand in its production. It is part of a series of papers written to inform public debate on development and humanitarian policy issues. For further information on the issues raised in this paper please email Mohamed Ouchene ([email protected]) or Philippe Massebiau ([email protected]). This publication is copyright but the text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, permission must be secured and a fee may be charged. -

Gender and Generation in the Sahrawi Struggle for Decolonisation

REGENERATING REVOLUTION: Gender and Generation in the Sahrawi Struggle for Decolonisation by Vivian Solana A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology in a Collaborative with the Women and Gender Studies Institute University of Toronto © Copyright by Vivian Solana, 2017 Regenerating Revolution: Gender and Generation in the Sahrawi Struggle for Decolonisation Vivian Solana Department of Anthropology in a Collaborative with the Women and Gender Studies Institute University of Toronto 2017 Abstract This dissertation investigates the forms of female labour that are sustaining and regenerating the political struggle for the decolonization of the Western Sahara. Since 1975, the Sahrawi national liberation movement—known as the POLISARIO Front—has been organizing itself, while in exile, into a form commensurable with the global model of the modern nation-state. In 1991, a UN mediated peace process inserted the Sahrawi struggle into what I describe as a colonial meantime. Women and youth—key targets of the POLISARIO Front’s empowerment policies—often stand for the movement’s revolutionary values as a whole. I argue that centering women’s labour into an account of revolution, nationalism and state-building reveals logics of long duree and models of female empowerment often overshadowed by the more “spectacular” and “heroic” expressions of Sahrawi women’s political action that feature prominently in dominant representations of Sahrawi nationalism. Differing significantly from globalised and modernist valorisations of women’s political agency, the model of female empowerment I highlight is one associated to the nomadic way of life that predates a Sahrawi project of revolutionary nationalism. -

EXILE, CAMPS, and CAMELS Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge Among Sahrawi Refugees

EXILE, CAMPS, AND CAMELS Recovery and adaptation of subsistence practices and ethnobiological knowledge among Sahrawi refugees GABRIELE VOLPATO Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees Gabriele Volpato Thesis committee Promotor Prof. Dr P. Howard Professor of Gender Studies in Agriculture, Wageningen University Honorary Professor in Biocultural Diversity and Ethnobiology, School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent, UK Other members Prof. Dr J.W.M. van Dijk, Wageningen University Dr B.J. Jansen, Wageningen University Dr R. Puri, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK Prof. Dr C. Horst, The Peace Research Institute, Oslo, Norway This research was conducted under the auspices of the CERES Graduate School Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees Gabriele Volpato Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Monday 20 October 2014 at 11 a.m. in the Aula. Gabriele Volpato Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees, 274 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2014) With references, with summaries in Dutch and English ISBN 978-94-6257-081-8 To my mother Abstract Volpato, G. (2014). Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees. PhD Thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands. With summaries in English and Dutch, 274 pp. -

Morocco's Sovereignty Over Natural Resources in Saharan Provinces

POLICY PAPER January 2020 Morocco’s Sovereignty over Natural Resources in Saharan provinces - Taking Cherry Blossom Case as an Example - Shoji Matsumoto PP-20/01 About Policy Center for the New South The Policy Center for the New South (PCNS) is a Moroccan think tank aiming to contribute to the improvement of economic and social public policies that challenge Morocco and the rest of the Africa as integral parts of the global South. The PCNS pleads for an open, accountable and enterprising «new South» that defines its own narratives and mental maps around the Mediterranean and South Atlantic basins, as part of a forward-looking relationship with the rest of the world. Through its analytical endeavours, the think tank aims to support the development of public policies in Africa and to give the floor to experts from the South. This stance is focused on dialogue and partnership, and aims to cultivate African expertise and excellence needed for the accurate analysis of African and global challenges and the suggestion of appropriate solutions. As such, the PCNS brings together researchers, publishes their work and capitalizes on a network of renowned partners, representative of different regions of the world. The PCNS hosts a series of gatherings of different formats and scales throughout the year, the most important being the annual international conferences «The Atlantic Dialogues» and «African Peace and Security Annual Conference» (APSACO). Finally, the think tank is developing a community of young leaders through the Atlantic Dialogues Emerging Leaders program (ADEL) a space for cooperation and networking between a new generation of decision-makers and entrepreneurs from the government, business and social sectors. -

Algeria and Morocco in the Western Sahara Conflict Michael D

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Hegemonic Rivalry in the Maghreb: Algeria and Morocco in the Western Sahara Conflict Michael D. Jacobs University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Scholar Commons Citation Jacobs, Michael D., "Hegemonic Rivalry in the Maghreb: Algeria and Morocco in the Western Sahara Conflict" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4086 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hegemonic rivalry in the Maghreb: Algeria and Morocco in the Western Sahara conflict by Michael Jacobs A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Government and International Affairs College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Earl Conteh-Morgan, Ph.D Committee 1: Mark Amen, Ph.D Committee 2: Prayutsha Bash, Ph.D Date of Approval July 5, 2012 Keywords: Northwest Africa, Sahrawi, Polisario Front, stability Copyright © 2012; Michael Jacobs Table of Contents Chapter 1: Conceptualizing Algeria in the Western Sahara Conflict 2 Chapter 2: The regionalization -

The Unfinished Referendum Process in Western Sahara

The Unfinished Referendum Process in Western Sahara By Terhi Lehtinen Terhi Lehtinen is the Programme Officer at the European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM), Onze Lieve Vrouweplein 21, 6211 HE Maastricht, The Netherlands; Tel: +31 43 350 2923; Fax: +31 43 350 2902; E-mail [email protected] Abstract The Western Saharan conflict, between Morocco and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el Hamra and Rio de Oro (Polisario), has constituted a major threat to regional stability in North Africa since the Spanish decolonisation in 1975. The war has cost thousands of lives, with prisoners of war taken on both sides, and forced Morocco to construct a huge fortified wall in the Sahara. The conflicting parties have a fundamental disagreement on the status of Sahara; Morocco claims its marocanity based on the region’s historical ties with Moroccan dynasties. In contrast, the Polisario fights for the Sahrawi people’s right to self-determination, bolstered by Organization of African Unity (OAU) principles and United Nations (UN) resolutions. However, the underlying dispute concerns the control of the region’s rich phosphate and fish resources. The UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (Minurso) has played the major role in the organisation of the referendum for self-determination, delayed several times due to disagreement on the voter identification and registration. In January 2001, the Polisario declared the end of the ceasefire, effective since 1991, due to Morocco’s failure to respect the agreed principles. The political settlement of the dispute remains difficult to achieve and frustration on the ground is increasing. -

Western-Sahara-FAQ.Pdf

At this very moment thousands of men, women and children are caught in the middle of a three decades old political conflict in the middle of the Sahara desert. Recently the Moroccan American Center for Policy (MACP) sponsored the visit of a delegation of former Sahrawi refugees to bring awareness about this forgotten humanitarian crisis. The Sahrawi delegation was made up of eight courageous individuals, all of whom managed to escape the refugee camps in Tindouf, Southern Algeria which are controlled by the Polisario Front, an Algerian-backed separatist group. Each had a personal story of how their lives, families and future have been affected— interrupted—by the politically motivated and cruel practices of the Polisario. However, they shared one common message: the separation of families and the oppression of the Sahrawi people must come to an end. F R E Q U E N T L Y A S K E D Q U E S T I O N S Q. What is the Polisario Front? A. The Poisario Front (a Spanish acronym for the “Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el Hamra and Rio de Oro”) was formed in 1973 as an independence movement against the Spanish colonization in the Sahara. After Spain relinquished the territory, the Polisario Front radically changed its mission and became the separatist group that it is today. The group was supported and armed by Algeria, Libya and Cuba in there respective attempts to undermine and destabilize United States ally, Morocco. Q. Are the Sahrawi people Moroccan? A. Yes. As early as 1578, the nomadic Bedouin tribes who inhabited the Sahara paid allegiance to the Moroccan Sultan (Moulay Ahmed El Mansour)—over 300 years before the arrival of the Spanish colonizers in 1884. -

Amanar Nature

Under the same sky with Amanar Published on Nature Astronomy on 5 March 2020: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-020-1053-z Sandra Benítez Herrera1 and Jorge Rivero González2 on behalf of the GalileoMobile Team 1Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain. 2Leiden Observatory, Leiden, the Netherlands. e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] The support of the international astronomical community to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is fundamental to advance the rights and needs of the most vulnerable groups of our global society. Among these groups are the refugees. Due to its technological, scientific and cultural dimensions, astronomy is a unique discipline to help achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [1]. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there are currently nearly 30 million refugees in the world. While there are many (and very necessary) programmes supporting their basic needs, different indicators suggest that the resolution to refugee and internal displacement situations require not only humanitarian interventions, but also development-led actions [2]. One of these initiatives is Amanar: Under the Same Sky, a project designed to support the Sahrawi refugee community by using astronomy to enhance their resilience and engagement in the community, through skill development and self-empowerment activities. The Sahrawi refugee situation is one of the most protracted in the world, with refugees living in camps near Tindouf, Algeria, since 1975. Access to basic resources is very limited and UN agencies have identified urgent humanitarian needs [2]. On one hand, fresh food, water, and medical and hygiene supplies are scarce in the camps, and Saharawi families depend on international assistance to survive.