A Case Study of Western Sahara, Africa's Last Colony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War and Insurgency in the Western Sahara

Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. STRATEGIC STUDIES INSTITUTE The Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) is part of the U.S. Army War College and is the strategic-level study agent for issues relat- ed to national security and military strategy with emphasis on geostrategic analysis. The mission of SSI is to use independent analysis to conduct strategic studies that develop policy recommendations on: • Strategy, planning, and policy for joint and combined employment of military forces; • Regional strategic appraisals; • The nature of land warfare; • Matters affecting the Army’s future; • The concepts, philosophy, and theory of strategy; and, • Other issues of importance to the leadership of the Army. Studies produced by civilian and military analysts concern topics having strategic implications for the Army, the Department of Defense, and the larger national security community. In addition to its studies, SSI publishes special reports on topics of special or immediate interest. These include edited proceedings of conferences and topically-oriented roundtables, expanded trip reports, and quick-reaction responses to senior Army leaders. The Institute provides a valuable analytical capability within the Army to address strategic and other issues in support of Army participation in national security policy formulation. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press WAR AND INSURGENCY IN THE WESTERN SAHARA Geoffrey Jensen May 2013 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. -

Ali El Aallaoui GENESIS and EVOLUTION of SAHARAWI

Ali El Aallaoui GENESIS AND EVOLUTION OF SAHARAWI NATIONALISM The Saharawi proverb "Sahara belonged neither to a king, nor to a devil, nor to a sultan" is inked in the Saharawi historical memory as a pledge of the independence of the Saharawi people against the authority of the Sultans of Morocco. Indeed, it somehow expresses the fact that Western Sahara had not been dominated before the arrival of Spain by any Moroccan king. It is this fact that characterizes modern Saharawi nationalism in terms of its discourse and arguments. That is to say, for the Saharawis the refusal of the Sultanian authority throughout history is the backbone around which the Saharawi cultural and political identity has crystallized. With the wave of decolonization which shook all the territories of the African continent, Saharawi nationalism entered the arena of peoples who aspire to their independence by all possible and legitimate means. It should be understood from the outset that Saharawi nationalism falls into the historical category of African nationalism, having transformed a nomadic people into a people seeking its political identity within the international community. This was ultimately manifested in the creation of a new state in exile, called the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). It is through a historical perspective that began with the movement of decolonization in Africa that we can understand the origins of Saharawi nationalism. This prompts us to ask the question, how does a nation differ from another nation, in our case, the Saharawi from the Moroccan? In other words, what is the specificity of Saharawi nationalism, which is still developing under the colonial yoke? All this, to answer a fundamental question, how could Saharawi nationalism defend the Saharawi political identity in the quest for independence, despite the Spanish and Moroccan complicity against the Saharawi people? The theoretical framework of Saharawi nationalism Saharawi nationalism is circumscribed within the framework of the principle of the right of peoples to dispose of themselves. -

Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Eric James Schmidt 2018 © Copyright by Eric James Schmidt 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger by Eric James Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Timothy D. Taylor, Chair This dissertation examines how Tuareg people in Niger use music to reckon with their increasing but incomplete entanglement in global neoliberal capitalism. I argue that a variety of social actors—Tuareg musicians, fans, festival organizers, and government officials, as well as music producers from Europe and North America—have come to regard Tuareg music as a resource by which to realize economic, political, and other social ambitions. Such treatment of culture-as-resource is intimately linked to the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism, which has led individual and collective subjects around the world to take on a more entrepreneurial nature by exploiting representations of their identities for a variety of ends. While Tuareg collective identity has strongly been tied to an economy of pastoralism and caravan trade, the contemporary moment demands a reimagining of what it means to be, and to survive as, Tuareg. Since the 1970s, cycles of drought, entrenched poverty, and periodic conflicts have pushed more and more Tuaregs to pursue wage labor in cities across northwestern Africa or to work as trans- ii Saharan smugglers; meanwhile, tourism expanded from the 1980s into one of the region’s biggest industries by drawing on pastoralist skills while capitalizing on strategic essentialisms of Tuareg culture and identity. -

KFOS LOCAL and INTERNATIONAL VOLUME II.Pdf

EDITED BY IOANNIS ARMAKOLAS AGON DEMJAHA LOCAL AND AROLDA ELBASANI STEPHANIE SCHWANDNER- SIEVERS INTERNATIONAL DETERMINANTS OF KOSOVO’S STATEHOOD VOLUME II LOCAL AND INTERNATIONAL DETERMINANTS OF KOSOVO’S STATEHOOD —VOLUME II EDITED BY: IOANNIS ARMAKOLAS AGON DEMJAHA AROLDA ELBASANI STEPHANIE SCHWANDNER-SIEVERS Copyright ©2021 Kosovo Foundation for Open Society. All rights reserved. PUBLISHER: Kosovo Foundation for Open Society Imzot Nikë Prelaj, Vila 13, 10000, Prishtina, Kosovo. Issued in print and electronic formats. “Local and International Determinants of Kosovo’s Statehood: Volume II” EDITORS: Ioannis Armakolas Agon Demjaha Arolda Elbasani Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers PROGRAM COORDINATOR: Lura Limani Designed by Envinion, printed by Envinion, on recycled paper in Prishtina, Kosovo. ISBN 978-9951-503-06-8 CONTENTS ABOUT THE EDITORS 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 12 INTRODUCTION 13 CULTURE, HERITAGE AND REPRESENTATIONS 31 — Luke Bacigalupo Kosovo and Serbia’s National Museums: A New Approach to History? 33 — Donjetë Murati and Stephanie Schwandner- Sievers An Exercise in Legitimacy: Kosovo’s Participation at 1 the Venice Biennale 71 — Juan Manuel Montoro Imaginaries and Media Consumptions of Otherness in Kosovo: Memories of the Spanish Civil War, Latin American Telenovelas and Spanish Football 109 — Julianne Funk Lived Religious Perspectives from Kosovo’s Orthodox Monasteries: A Needs Approach for Inclusive Dialogue 145 LOCAL INTERPRETATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL RULES 183 — Meris Musanovic The Specialist Chambers in Kosovo: A Hybrid Court between -

The Legal Issues Involved in the Western Sahara Dispute

The Legal Issues Involved In The Western Sahara Dispute The Principle of Self-Determination and the Legal Claims of Morocco COMMITTEE ON THE UNITED NATIONS JUNE 2012 NEW YORK CITY BAR ASSOCIATION 42 WEST 44TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10036 THE LEGAL ISSUES INVOLVED IN THE WESTERN SAHARA DISPUTE THE PRINCIPLE OF SELF-DETERMINATION Table of Contents Contents Page PART I: FACTUAL BACKGROUND....................................................................................... 3 PART II: ENTITLEMENT OF THE PEOPLE OF WESTERN SAHARA TO SELF- DETERMINATION UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW ........................................................... 22 I. THE RIGHT TO SELF-DETERMINATION UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW: GENERAL PRINCIPLES ............................................................................................................ 22 A. Historical Development of the Right to Self-Determination ................................................ 23 B. The United Nations Charter and Non-Self-Governing Territories ....................................... 26 C. Status of Right as Customary Law and a Peremptory Norm ................................................ 27 D. People Entitled to Invoke the Right ...................................................................................... 32 E. Geographic Boundaries on the Right to Self-Determination ................................................ 34 F. Exceptions to the Right to Self-Determination ..................................................................... 38 II. THE COUNTERVAILING RIGHT TO TERRITORIAL -

Amazight Identity in the Post Colonial Moroccan State

Oberlin College Amazight Identity in The Post Colonial Moroccan State: A Case Study in Ethnicity An Honors Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology by Morag E. Boyd Oberlin, Ohio April, 1997 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisers in Morocco, Abdelhay Moudden and Susan Schaefer Davis for the direction they gave me, but also for the direction that they did not. My honors adviser, Jack Glazier, was vital in the development of this thesis from the product of a short period of research to the form it is in now; I am grateful for his guidance. I would also like to thank the entire Oberlin College Department of Anthropology for guiding and supporting me during my discovery of anthropology. Finally, I must thank my family and friends for their support, especially Josh. Table of Contents Chapter one: Introduction . 1 I: Introduction . 1 II: Fieldwork and Methodology .3 Chapter two: Theoretical Foundations .7 I: Ethnicity ..... 7 II: Political Symbolism .15 Chapter three: History, Organization, and Politics . 19 I: Historical Background .. ........... .. ... 19 II: Ramifications of Segmentary Lineage and Tribal Heritage . 22 Segmentary Lineage and Tribes Tribes, Power, and Politics Political Heritage and Amazight Ethnicity III: Arabization and Colonization . .. .. .. .. .. .. 33 Contemporary ramification IV: Amazight identity and government today .... .. .. 39 Chapter four: Finding Amazight Ethnicity . 44 I: Perceptions of Amazight Identity . 44 Markers of Ethnicity Ethnic Boundaries and Maintenance of ethnic Identity Basic Value Orientation Significance of Amazight Ethnicity Common History as a Source of Group Cohesion Urban and Rural Divide II: Language.... ...... ... .... .. ...... 54 Language and Education Daily Language III: Religion ' .60 IV: Conclusions .63 Chapter Five: Conclusions . -

When Refugee Camp and Nomadic Encampment Meet

Ambiguities of space and control: when refugee camp and nomadic encampment meet Article (Accepted Version) Wilson, Alice (2014) Ambiguities of space and control: when refugee camp and nomadic encampment meet. Nomadic Peoples, 18 (1). pp. 38-60. ISSN 0822-7942 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/70245/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Alice Wilson Author’s accepted manuscript, later published as the article Wilson, A. (2014) “Ambiguities of space and control: when refugee camp and nomadic encampment meet”. -

Modern Moroccan Music Is a Westernized Version Driss Ridouani*

Проблеми на постмодерността, Том II, Брой 1, 2012 Postmodernism problems, Volume 2, Number 1, 2012 Modern Moroccan Music is a Westernized Version Driss Ridouani* Abstract With the advancement of means of communication especially in the modern era, we have become more aware of the scope where nations constitute an ineluctable part system of the world at large. In fact, what is nowadays called individual societies and considered as independent entities do not exist any more for their local distinctive standard can be recognized only within the global framework. Hence, besieged and governed by mass media, the world at large has been transformed into what McLuhan cogently termed “Global Village”, paving the way for the expansion of foreign powers over the poor societies. In order to gain insight into an individual society, we would consider it as an integrated part of the global whole together with the external, say Western, factors that forcibly influence its fundamental principles. The scope of the impact is so wide and its nature is so various that it encompasses all nations together with their institutions. This paper is an attempt to investigate the way the cultural framework of Moroccan society is “Westernized”, drawing on the popular music and the changes that have shaped both its content and form. In the same vein, scholars of different interest and aim, chiefly Moroccan ones, underline the process of transformation that has been incessantly happening in popular music, pointing especially to the integration and assimilation of Western characteristics. Such a situation leads to a crucial question why Moroccan popular music has made room for external influences while sloughing off its originality and its essence. -

Periodic Report of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic

PERIODIC REPORT OF THE SAHRAWI ARAB DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC TO THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES RIGHTS CONTAINING ALL THE OUTSTANDING REPORTS IN ACCORDANCE WITH ARTICLE 62 OF THE CHARTER October 2011 i Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Part I: Data on the General Framework for the Promotion of Human Rights in the Sahrawi Republic in Accordance with the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights ........................... 7 Chapter One: General Information About the Sahrawi Republic ....................................................... 7 i) The Region ...................................................................................................................................... 7 ii) Population ........................................................................................................................................ 7 iii) Language ..................................................................................................................................... 7 iv) Economy ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter Two: The Process of Democratization in Western Sahara ................................................. 8 Chapter Three: The Legal and Institutional Framework for the Promotion of Human Rights in the Sahrawi Republic .............................................................................................................................. -

Sahrawi Women in the Liberation Struggle of the Sahrawi People Author(S): Anne Lippert Source: Signs, Vol

Sahrawi Women in the Liberation Struggle of the Sahrawi People Author(s): Anne Lippert Source: Signs, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Spring, 1992), pp. 636-651 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174626 Accessed: 18/05/2010 18:01 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs. http://www.jstor.org REVISIONS / REPORTS SahrawiWomen in the Liberation Struggle of the SahrawiPeople Anne Lippert Introduction - T H R O U G H T H E I R R O LE S in the currentliberation strug- gle of the Sahrawisof WesternSahara, Sahrawi women have substantiallyincreased their traditionalparticipation and im- portance in that society. -

Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps

Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-420-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org December 2008 1-56432-420-6 Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Map Of North Africa ....................................................................................................... 1 Summary...................................................................................................................... 2 Western Sahara ....................................................................................................... 3 Refugee Camps near Tindouf, Algeria ...................................................................... 8 Recommendations ...................................................................................................... 12 To the UN Security Council ..................................................................................... 12 Recommendations to the Government of Morocco .................................................. 12 Recommendations Regarding Human Rights in the Tindouf Camps ........................ -

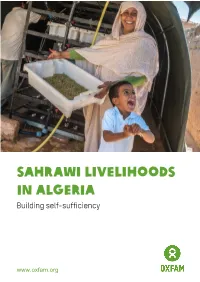

Sahrawi Livelihoods in Algeria: Building Self

Sahrawi livelihoods in algeria Building self-sufficiency www.oxfam.org OXFAM CASE STUDY – SEPTEMBER 2018 Over 40 years ago, Oxfam began working with Sahrawi refugees living in extremely harsh conditions in camps in the Saharan desert of western Algeria, who had fled their homes as a result of ongoing disputes over territory in Western Sahara. Since then, the Sahrawi refugees have been largely dependent on humanitarian aid from a number of agencies, but increasing needs and an uncertain funding future have meant that the agencies are having to adapt their programme approaches. Oxfam has met these new challenges by combining the existing aid with new resilience-building activities, supporting the community to lead self-sufficient and fulfilling lives in the arid desert environment. © Oxfam International September 2018 This case study was written by Mohamed Ouchene and Philippe Massebiau. Oxfam acknowledges the assistance of Meryem Benbrahim; the country programme and support teams; Eleanor Parker; Jude Powell; and Shekhar Anand in its production. It is part of a series of papers written to inform public debate on development and humanitarian policy issues. For further information on the issues raised in this paper please email Mohamed Ouchene ([email protected]) or Philippe Massebiau ([email protected]). This publication is copyright but the text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, permission must be secured and a fee may be charged.