A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toole, John Kennedy (1936-1969) by Raymond-Jean Frontain

Toole, John Kennedy (1936-1969) by Raymond-Jean Frontain Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2004, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Since its publication in 1980, John Kennedy Toole's A Confederacy of Dunces has been celebrated as the quintessential novel of post-World War II New Orleans. It offers as vibrant and telling a portrait of the Crescent City as John Berendt's Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil does of Savannah, or Armistead Maupin's Tales of the City does of San Francisco. New Orleans--with its mix of French, Spanish, and Afro-Creole cultures, and its history as a pirates' refuge and a pleasure seeker's delight-- is a rewarding subject for a novelist like Toole, who is interested both in exposing social hypocrisy and in celebrating the ability of the socially marginalized not simply to survive, but to live with gusto in the face of the majority's disapproval. Toole, however, seems never to have fully accepted his homosexuality, and his writing reflects his discomfort with this marker of his own marginalization. The paradox of Toole's life and career is that the man who created such comically vibrant and emotionally resilient characters as Aunt Mae, Ignatius J. Reilly, Santa Battaglia, and Burma Jones should have committed suicide at only age 32. Biography Toole was born on December 17, 1936, the only son of a couple in their late 30s who had resigned themselves to remaining childless. His father was an ineffective but entertaining man who worked as an automobile salesman and mechanic before deafness and failing health forced him into early retirement. -

Changing Hearts and Minds to Value Education Dear Parents, Guardians

THE NEWARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS Central High School 246-250 18th Avenue Newark, New Jersey 07108 Phone: 973-733-6897 Fax: 973-733-8212 Christopher Cerf Kimberley Harrington (Acting) State District Superintendent Commissioner of Education Sharnee Brown Principal Dear Parents, Guardians, and Students, At Central High School, student success is our greatest priority. To that end, your child is required to read a novel during the summer. Reading builds not only literacy skills needed for the PARCC and other exams, but it also builds vocabulary, writing, speaking, listening, comprehension, interpretation, and analysis skills that will benefit them in all aspects of their goals. Reading helps develop foundations in other academic subjects as authors often reference history, mathematics, science, and other topics within the greater purpose for their literary works. Current research on summer reading shows that a several-month break in reading activities can hinder academic growth. Our efforts were focused on providing students with engaging texts that will prepare them for success in the curriculum during the upcoming school year. The intention of this summer reading program is to support continued use of the reading strategies we have learned throughout the school year while providing our students with the opportunity to pass the summer months with both enjoyment and mental exercise. The summer reading program is mandatory, with the connected assignment due for an assessment grade during Week 1 (September 5-8, 2017) of the upcoming school year. Please see the list on the next pages, which contain the novel students in each grade level are expected to read, as well as the associated assignment. -

(For an Exceptional Debut Novel, Set in the South) Names Final Four

FOR RELEASE NOVEMBER 20 FIRST ANNUAL CROOK’S CORNER BOOK PRIZE (FOR AN EXCEPTIONAL DEBUT NOVEL, SET IN THE SOUTH) NAMES FINAL FOUR The linkages between good writing and good food and drink are clear and persistent. I can’t imagine a better means of celebrating their entwining than this innovative award. — John T. Edge CHAPEL HILL, NC – The Crook’s Corner Book Prize announced four finalists for the first annual Crook’s Corner Book Prize, to be awarded for an exceptional debut novel set in the American South. The winner will be announced January 6th. The four finalists are LEAVING TUSCALOOSA, by Walter Bennett (Fuze Publishing); CODE OF THE FOREST, by Jon Buchan (Joggling Board Press); A LAND MORE KIND THAN HOME, by Wiley Cash (William Morrow); and THE ENCHANTED LIFE OF ADAM HOPE, by Rhonda Riley (Ecco). “It was exciting to find so many great books—several of them from independent publishers (even micro-publishers)—emerging from our reading,” said Anna Hayes, founder and president of the Crook’s Corner Book Prize Foundation. “This grassroots effort to discover and champion books in general, Southern Literature in particular, is amazing and refreshing,” said Jamie Fiocco, owner of Flyleaf Books and president of the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance. “The Crook’s Corner Book Prize is a great example of what independent booksellers have been doing for years: finding top- quality reading experiences, regardless of the book’s origin—small or large publisher. Readers trust the rich literary history of the South to deliver a sense of place and great characters; now this Prize lets readers learn about the cream of the crop of new storytellers.” Intended to encourage emerging writers in a publishing environment that seems to change daily, the Prize is equally open to self-published authors and traditionally published authors. -

Literature Review Form to Kill a Mockingbird

Southwest Licking School District Literature Selection Review Teacher: Paula Ball School: Watkins Memorial High School Book Title: To Kill a Mockingbird Genre: Fiction Author: Harper Lee Publisher: Warner Brothers Book Summary and summary citation: Set in the small Southern town of Maycomb, Alabama, during the Depression, To Kill a Mockingbird follows three years in the life of 8-year-old Scout Finch, her brother, Jem, and their father, Atticus--three years punctuated by the arrest and eventual trial of a young black man accused of raping a white woman. Though her story explores big themes, Harper Lee chooses to tell it through the eyes of a child. The result is a tough and tender novel of race, class, justice, and the pain of growing up. Instructional Rationale/Objectives: Read increasingly challenging texts, comparing these texts to previously read texts Identify, analyze, and evaluate persuasive techniques used in literature Review #1 Amazon.com Review Like the slow-moving occupants of her fictional town, Lee takes her time getting to the heart of Her tale; we first meet the Finches the summer before Scout's first year at school. She, her brother, and Dill Harris, a boy who spends the summers with his aunt in Maycomb, while away the hours reenacting scenes from Dracula and plotting ways to get a peek at the town bogeyman, Boo Radley. At first the circumstances surrounding the alleged rape of Mayella Ewell, the daughter of a drunk and violent white farmer, barely penetrate the children's consciousness. Then Atticus is called on to defend the accused, Tom Robinson, and soon Scout and Jem find themselves caught up in events beyond their understanding. -

Honors/Advanced Placement English III Reading List 2008-2009

Honors/Advanced Placement English III Summer Reading List 2021 English III (H) and (AP): Students are required to take Accelerated Reader tests on assigned and choice novels. • Novel: Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger • Film: Dead Poets’ Society (1989—PG) • Also: Students will read one work from the list provided below. This selection will feed into a major research project to be completed during the junior year. Students who read more than one book from this list can use these points toward an extra AR grade for summer/1st quarter and will also ease their reading requirements during the first quarter of junior year. Note: Any points over 15 earned on this choice book will count toward your first-quarter bonus AR grade. Points earned from The Catcher in the Rye do not count toward a bonus grade. Have questions? Contact me: [email protected] Important to note: I strongly encourage you to annotate your books as you read. Suggestions for why and how are provided in the great article available through this link: https://slowreads.com/2008/04/18/how-to-mark-a-book/ Choose from these books: American Male Writers The Big Sleep / Raymond Chandler: a dark and cynical mystery/detective story with a plot that reveals how truly twisted the human heart is; also presents us with a heroic detective who shows that chivalry is not completely dead in modern society. AR: 15 The Call of the Wild /Jack London: The story, filled with action and adventure, presents a strangely compelling world - the world of the Arctic Circle at the beginning of the 20th century. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Empathy: a Learning Framework

BOOKS@WORK EMPATHY: A LEARNING FRAMEWORK Empathy: a curriculum for self-reflection What is Books@Work? In her classic novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee’s unforgettable Books@Work is a highly hero, Atticus Finch, cautions his daughter Scout not to rush to judgment of interactive program in others: “you never really understand a person until you consider things which college professors from his point of view...until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” work with frontline While we casually accept that empathy requires putting ourselves in the employees to jointly place of another, what does it really mean to have empathy for others or explore and reflect upon to respect diverse perspectives in a just, meaningful and personally relevant broad themes in an way? enjoyable and engaging Working with narratives and texts from diverse cultures, disciplines and seminar. The sponsor of time periods, readers explore how empathy differs from sympathy. A Books@Work, That Can Be subtle difference, empathy requires an individual to feel what another feels Me, Inc., has developed a (e.g., “I feel your pain”), while sympathy generates an emotional response series of curricular learning to another’s feelings (e.g., “I feel sorry for your pain”) 1. frameworks focused on several popular themes, Authentic empathy requires a deep understanding of the self in relation to with the input and others. But where empathy requires us to go above and beyond, must one guidance of both protect the self from engaging too deeply with others? Where does the employers and professors. -

To Kill a Mockingbird Background Information Harper Lee Was An

To Kill a Mockingbird Background Information Harper Lee was an American writer, famous for her race relations novel TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1961. The book became an international bestseller and was adapted into screen in 1962. Lee was 34 when the work was published, and it has remained her only novel. "Mockingbirds don't do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don't eat up people's gardens, don't nest in corncribs, they don't do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That's why it's a sin to kill a mockingbird." Harper Lee was born in Monroeville, Alabama. Her father was a former newspaper editor and proprietor, who had served as a state senator and practiced as a lawyer in Monroeville. Lee studied law at the University of Alabama from 1945 to 1949, and spent a year as an exchange student in Oxford University, Wellington Square. Six months before finishing her studies, she went to New York to pursue a literary career. During the 1950s, she worked as an airline reservation clerk with Eastern Air Lines and British Overseas Airways. In 1959 Lee accompanied Truman Capote to Holcombe, Kansas, as a research assistant for Capote's classic 'non-fiction' novel In Cold Blood (1966). To Kill a Mockingbird was Lee's first novel. The book is set in Maycomb, Alabama, in the 1930s. Atticus Finch, a lawyer and a father, defends a black man, Tom Robinson, who is accused of raping a poor white girl, Mayella Ewell. -

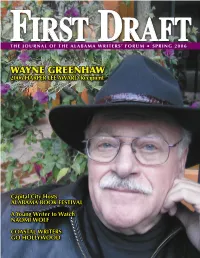

Vol. 12, No.2 / Spring 2006

THE JOURNAL OF THE ALABAMA WRITERS’ FORUM FIRST DRAFT• SPRING 2006 WAYNE GREENHAW 2006 HARPER LEE AWARD Recipient Capital City Hosts ALABAMA BOOK FESTIVAL A Young Writer to Watch NAOMI WOLF COASTAL WRITERS GO HOLLYWOOD FY 06 BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD MEMBER PAGE President LINDA HENRY DEAN Auburn Words have been my life. While other Vice-President ten-year-olds were swimming in the heat of PHILIP SHIRLEY Jackson, MS summer, I was reading Gone with the Wind on Secretary my screened-in porch. While my friends were JULIE FRIEDMAN giggling over Elvis, I was practicing the piano Fairhope and memorizing Italian musical terms and the Treasurer bios of each composer. I visited the local library DERRYN MOTEN Montgomery every week and brought home armloads of Writers’ Representative books. From English major in college to high JAMES A. BUFORD, JR. school English teacher in my early twenties, Auburn I struggled to teach the words of Shakespeare Writers’ Representative and Chaucer to inner-city kids who couldn’t LINDA C. SPALLA read. They learned to experience the word, even Huntsville Linda Spalla serves as Writers’ Repre- DARYL BROWN though they couldn’t read it. sentative on the AWF Executive Com- Florence Abruptly moving from English teacher to mittee. She is the author of Leading RUTH COOK a business career in broadcast television sales, Ladies and a frequent public speaker. Birmingham I thought perhaps my focus would be dif- JAMES DUPREE, JR. fused and words would lose their significance. Surprisingly, another world of words Montgomery appeared called journalism: responsibly chosen words which affected the lives of STUART FLYNN Birmingham thousands of viewers. -

Appendix B: a Literary Heritage I

Appendix B: A Literary Heritage I. Suggested Authors, Illustrators, and Works from the Ancient World to the Late Twentieth Century All American students should acquire knowledge of a range of literary works reflecting a common literary heritage that goes back thousands of years to the ancient world. In addition, all students should become familiar with some of the outstanding works in the rich body of literature that is their particular heritage in the English- speaking world, which includes the first literature in the world created just for children, whose authors viewed childhood as a special period in life. The suggestions below constitute a core list of those authors, illustrators, or works that comprise the literary and intellectual capital drawn on by those in this country or elsewhere who write in English, whether for novels, poems, nonfiction, newspapers, or public speeches. The next section of this document contains a second list of suggested contemporary authors and illustrators—including the many excellent writers and illustrators of children’s books of recent years—and highlights authors and works from around the world. In planning a curriculum, it is important to balance depth with breadth. As teachers in schools and districts work with this curriculum Framework to develop literature units, they will often combine literary and informational works from the two lists into thematic units. Exemplary curriculum is always evolving—we urge districts to take initiative to create programs meeting the needs of their students. The lists of suggested authors, illustrators, and works are organized by grade clusters: pre-K–2, 3–4, 5–8, and 9– 12. -

A Masterpiece Also a Hoax?

BOOKS BOOKS Republic. Poor impatient John Kennedy Toole! But, on the other hand, isn't this A Masterpiece every young novelist's secret dream? I just don't believe it. I've got no proof one way or the other, but every in stinct tells me that A Conjederacy of Also a Hoax? Dunces is some kind of hoax. 1) The name John Kennedy Toole is like a flag before my eyes. It just looks weird, especially since the book.)s set in the early 1960s. 2) Ditto for the story about Mother Toole. Not that she herself is implausible; but I've run into her in too many other novels. 3) I don't believe "Toole" couldn't find a publisher. It's a myth, prized by mediocre writers, especially out here in the provinces, that the very writing ofterui~er sees the lisht of day. I. 4) t ""~n't believe •')at. i~ 1980, tile b ok,. C:Ould fsiiy II,; 'ii oA"··~••w\. ~ •.;, '"· ·-· UnI~ty press. S) Look api~ t the bool's ero, I1natius R · y. the movtegoing, madly arroga , pseudo aristoctatic, me · · ew Orleans Catholic rebel. "I dust a bit. I am at the moment writing a lengthy indictment against 0ur century. I make an occa sional cheese dip." Who's kidding whom here? A Confederacy of Dunces reads like nothing so much as a parody of the ideas, novels and even person of its midwife, Walker Percy. I'm not quite Lisa Alther ready to say that Percy is Toole because of the apparent radical dif ferences in their writing styles. -

Pulitzer Prize

1946: no award given 1945: A Bell for Adano by John Hersey 1944: Journey in the Dark by Martin Flavin 1943: Dragon's Teeth by Upton Sinclair Pulitzer 1942: In This Our Life by Ellen Glasgow 1941: no award given 1940: The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck 1939: The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Prize-Winning 1938: The Late George Apley by John Phillips Marquand 1937: Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell 1936: Honey in the Horn by Harold L. Davis Fiction 1935: Now in November by Josephine Winslow Johnson 1934: Lamb in His Bosom by Caroline Miller 1933: The Store by Thomas Sigismund Stribling 1932: The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1931 : Years of Grace by Margaret Ayer Barnes 1930: Laughing Boy by Oliver La Farge 1929: Scarlet Sister Mary by Julia Peterkin 1928: The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thornton Wilder 1927: Early Autumn by Louis Bromfield 1926: Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis (declined prize) 1925: So Big! by Edna Ferber 1924: The Able McLaughlins by Margaret Wilson 1923: One of Ours by Willa Cather 1922: Alice Adams by Booth Tarkington 1921: The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton 1920: no award given 1919: The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkington 1918: His Family by Ernest Poole Deer Park Public Library 44 Lake Avenue Deer Park, NY 11729 (631) 586-3000 2012: no award given 1980: The Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer 2011: Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 1979: The Stories of John Cheever by John Cheever 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding 1978: Elbow Room by James Alan McPherson 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 1977: No award given 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 1976: Humboldt's Gift by Saul Bellow 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 1975: The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 1974: No award given 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson 1973: The Optimist's Daughter by Eudora Welty 2004: The Known World by Edward P.