From ADIZ to SFRA: the AF A's Compliance with Administrative Procedures to Codify Washington, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 2020 DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR AIRFIELD IMPROVEMENTS AT BAY BRIDGE AIRPORT STEVENSVILLE, MARYLAND PREPARED FOR: QUEEN ANNE’S COUNTY PREPARED BY: AECOM TECHNICAL SERVICES, INC. 4 NORTH PARK DRIVE, SUITE 300 HUNT VALLEY, MD 21030 June 2020 DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR AIRFIELD IMPROVEMENTS AT BAY BRIDGE AIRPORT STEVENSVILLE, MARYLAND PREPARED FOR: QUEEN ANNE’S COUNTY This Environmental Assessment becomes a Federal document when evaluated and signed by the responsible Federal Aviation Administration official. Responsible Federal Aviation Administration Official Date Federal Aviation Administration – Washington Airports District Office PREPARED BY: AECOM TECHNICAL SERVICES, INC. 4 NORTH PARK DRIVE, SUITE 300 HUNT VALLEY, MD 21030 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Section No. Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND PROPOSED ACTION .............................................................................................1-1 1.1 Introduction...................................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 Bay Bridge Airport ........................................................................................................................................1-1 1.3 Description of Proposed Action ....................................................................................................................1-2 1.4 Requested Federal Action ............................................................................................................................1-3 -

GWBAA Safety Standdown to Be Held on May 5Th

Facebook Twitter General Aviation Terminal, Hangar 7 Washington, DC 20001 www.gwbaa.com [email protected] April 28, 2016 GWBAA Safety Standdown To Be Held on May 5th Please Join Us for GWBAA's Tenth Annual Safety Event The Greater Washington Business Aviation Association will host its tenth annual Safety Standdown at the NTSB Training Facility in Ashburn, Virginia on May 5, starting at 7:30am. A networking reception will be held the evening before on May 4 at the DoubleTree Dulles Airport. This year's Keynote Speaker will be Bob Agostino, who is credited with being the father of the concept of the safety standdown, and who will discuss: "What is normal for today's professional flight department". The day will also include presentations by Bombardier on loss of control and jet upset; Honeywell on future aircraft requirements for navigation, communication and surveillance; NBAA with an industry and safety update; and Potomac TRACON with an ATC briefing. Sponsorship opportunities for the standdown are still available. For more information and to register or sponsor, please visit http://gwbaa.com/event-2076030. (Need a place to stay? Make a reservation by April 12 and ask for the GWBAA rate at the DoubleTree - (703) 230-0077.) Thanks to our sponsors: 1 GWBAA Holds Networking Luncheon at Signature BWI Many thanks to all who attended our event at BWI on April 21, and to Bryan Burns (President of the Air Charter Safety Foundation) for providing an update on the Aviation Safety Action Program (ASAP) for FAR Part 135 and FAR Part 91 operators. -

Federal Aviation Administration, DOT SFAR No. 50–2

Federal Aviation Administration, DOT SFAR No. 50±2 of this SFAR. The supplemental type certifi- long 112°08′47′′ W.) to lat. 35°57′30′′ N., long. cate will remain in effect until the approval 112°14′00′′ W.; to lat 35°57′30′′ N., long. to operate issued under the Special Federal 113°11′00′′ W.; to lat. 35°42′30′′ N., long. Aviation Regulation is surrendered, revoked, 113°11′00′′ W.; to lat. 35°38′30′′ N., long. or otherwise terminated. 113°27′30′′ W.; thence counterclockwise via 4. Notwithstanding § 91.167(a)(3) of the Fed- the 5-statute mile radius of the Peach eral Aviation Regulations, a person may op- Springs VORTAC to lat. 35°41′20′′ N., long. erate a rotorcraft in a limited IFR operation 113°36′00′′ W.; to lat. 35°55′25′′ N., long approved under paragraph 2(a) of the Special 113°49′10′′ W.; to lat. 35°57′45′′ N., long. Federal Aviation Regulation with enough 113°45′20′′ W.; thence northwest along the fuel to fly, after reaching the alternate air- park boundary to lat. 36°02′20′′ N., long. port, for not less than 30 minutes, when that 113°50′15′′ W.; to lat. 36°00′10′′ N., long., period of time has been approved. 113°53′45′′ W.; thence to the point of begin- 5. Expiration. ning. (a) New applications for limited IFR rotor- Sec. 2. Definitions. For the purposes of this craft operations under SFAR No. 29 may be special regulation: submitted for approval until, but not includ- Flight Standards District Office means the ing, the effective date of Amendment No. -

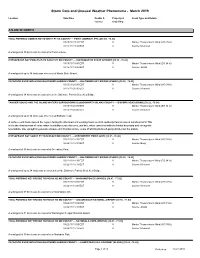

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena - March 2019

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena - March 2019 Location Date/Time Deaths & Property & Event Type and Details Injuries Crop Dmg ATLANTIC NORTH TIDAL POTOMAC COBB IS MD TO SMITH PT VA COUNTY --- POINT LOOKOUT (PTL) [38.04, -76.32] 03/15/19 19:34 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (MG 35 kt) 03/15/19 19:34 EST 0 Source: Mesonet A wind gust of 35 knots was measured at Point Lookout. CHESAPEAKE BAY POOLES IS TO SANDY PT MD COUNTY --- (KMTN)MARTIN STATE AIRPORT [39.33, -76.42] 03/15/19 19:45 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (EG 34 kt) 03/15/19 19:45 EST 0 Source: ASOS A wind gust of up to 34 knots was observed at Martin State Airport. PATAPSCO RIVER INCLUDING BALTIMORE HARBOR COUNTY --- BALTIMORE KEY BRIDGE (FSKM2) [39.22, -76.53] 03/15/19 20:00 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (MG 34 kt) 03/15/19 20:00 EST 0 Source: Mesonet A wind gust of 34 knots was measured near the Baltimore Francis Scott Key Bridge. TANGIER SOUND AND THE INLAND WATERS SURROUNDING BLOODSWORTH ISLAND COUNTY --- BISHOPS HEAD (BISM2) [38.22, -76.04] 03/15/19 20:06 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (EG 34 kt) 03/15/19 20:06 EST 0 Source: Mesonet A wind gust of up to 34 knots was observed at Bishops Head. A surface cold front crossed the region during the afternoon and evening hours as mild southerly flow increased out ahead of it. This led to the development of some minor instability across the area, and this, when combined with the frontal boundary and strong mid level winds, was enough to generate showers and thunderstorms, some of which produced gusty winds over the waters. -

Avery Print from the Web, V5 Document

Bernard Adams Joseph Arze Jocelyn Bernhardt Campus Director Senior Engineer Client Manager [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Pittsburgh Institute of Aeronautics All About Pavements, Inc. Arora Engineers, Inc. 14516 Pennsylvania Ave. 904 Strawberry Court One East Pratt Street, Suite 803 Hagerstown Maryland 21742 Purcellville Virginia 20132 Baltimore Maryland 21202 (240) 347-4805 (703) 508-1415 (443) 762-8245 www.allaboutpavements.com Michael Boone Kenneth Brazeau Edward Brink CFO Senior Airport Planner Program Flight Specialist [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Montgomery County Revenue Authority AECOM University of Maryland Eastern Shore 101 Monroe street, suite 410 4 North Park Drive, Suite 300 30925 College Backbone Road Rockville Maryland 20850 Hunt Valley Maryland 21030 Princess Anne Maryland 21853 (240) 338-3662 (443) 520-2827 (410) 430-8483 www.montgomerycountyairpark.com www.aecom.com www.umes.edu Kirsten Brown Chris Buchanan Tim Butera Airport Engineer Regional Sales Manager Vice President [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Urban Engineers Inc EPIC Fuels K2 Construction Consultants, Inc. One South Street 222 Las Colinas Blvd W 4330 East West Highway Baltimore Maryland 21202 Irving Texas 75039 Bethesda Maryland 20814 (215) 922-8080 (703) 945-2446 (202) 550-5533 www.urbanengineers.com epicfuels.com Jeff Castonguay Meighan Chisholm Sean Collins Director of Public Works Airport Manager, Cambridge-Dorchester Regional Eastern Regional -

Calendar No. 596

Calendar No. 596 106TH CONGRESS REPORT "! 2d Session SENATE 106±309 DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION AND RELATED AGENCIES APPROPRIATIONS BILL, 2001 JUNE 14, 2000.ÐOrdered to be printed Mr. SHELBY, from the Committee on Appropriations, submitted the following REPORT [To accompany S. 2720] The Committee on Appropriations reports the bill (S. 2720) mak- ing appropriations for the Department of Transportation and re- lated agencies for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2001, and for other purposes, reports favorably thereon and recommends that the bill do pass. Amounts of new budget (obligational) authority for fiscal year 2001 Amount of bill as reported to Senate ...................... $15,295,400,000 Amount of budget estimates, 2001 .......................... 16,146,737,000 Fiscal year 2000 enacted .......................................... 14,429,976,000 64±948 cc C O N T E N T S SUMMARY OF MAJOR RECOMMENDATIONS Page Total obligational authority .................................................................................... 5 TITLE IÐDEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY Immediate Office of the Secretary .......................................................................... 10 Immediate Office of the Deputy Secretary ............................................................ 11 Office of the General Counsel ................................................................................. 11 Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy ........................................................... 12 Office of the -

Unpublished United States Court of Appeals for The

UNPUBLISHED UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT MICHAEL K. SZABO, Petitioner, v. No. 94-2414 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD; ADMINISTRATOR, FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION Respondents. On Petition for Review of an Order of the Federal Aviation Administration. (SE-12794) Argued: November 1, 1995 Decided: February 5, 1996 Before ERVIN, Chief Judge, WILKINS, Circuit Judge, and MICHAEL, Senior United States District Judge for the Western District of Virginia, sitting by designation. _________________________________________________________________ Affirmed by unpublished per curiam opinion. _________________________________________________________________ COUNSEL ARGUED: Jay Fred Cohen, Baltimore, Maryland, for Petitioner. Susan S. Caron, Enforcement Division, Office of the Chief Counsel, FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION, Washington, D.C., for Respondents. ON BRIEF: Kathleen A. Yodice, Acting Manager, Appellate Branch, Enforcement Division, Office of the Chief Coun- sel, FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION, Washington, D.C., for Respondents. _________________________________________________________________ Unpublished opinions are not binding precedent in this circuit. See Local Rule 36(c). _________________________________________________________________ OPINION PER CURIAM: Petitioner Michael K. Szabo asks that we review an order of the National Transportation Safety Board ("the Board") suspending for thirty days his airman certificate. Finding no error, we affirm. I. On July 2, 1988, Marilyn Doncarlos landed her Mooney aircraft at Bay Bridge Airport in Stevensville, Maryland. As she turned off the runway on her "rollout," she noticed another aircraft, a Cherokee 180 operated by Szabo, approximately 300 feet behind her on the same runway she was leaving. Believing that Szabo's landing his aircraft so close to her aircraft violated Federal Aviation Administration ("FAA") safety regulations, Ms. Doncarlos reported the incident to the Baltimore Flight Standards District Office. -

The Future of Tipton Airport in Anne Arundel County

The Future of Tipton Airport in Anne Arundel County by Pranita Ranbhise Under the supervision of Professor Melina Duggal Course 788: Independent Study The University of Maryland- College Park Fall 2016 PALS - Partnership for Action Learning in Sustainability An initiative of the National Center for Smart Growth Gerrit Knaap, NCSG Executive Director Uri Avin, PALS Director, Kim Fisher, PALS Manager 1 Executive Summary Tipton Airport is located in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. It is a General (GA) airport, classified as a reliever airport by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). It is the reliever airport to the Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport (BWI), which is located less than 13 miles from Tipton. The airport plans to extend their runway from 3,000 feet to 4,200 feet. The main objective for this expansion is to increase the number of larger turbo-planes and business aircrafts, which require longer runways that can use the facility. This will expand the airport’s market reach and user base, allowing it to improve the ease of flying for potential users. The purpose of this study is to determine the future demand for corporate service and other air traffic at the airport in light of the runway expansion, and to recommend additional variables that will help increase air traffic. The report provides a detailed description of Tipton Airport, including its location and context, airport services, and a comparison of these services with similar airports in Maryland. It also includes an analysis of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats for the airport, based on a review of FAA records and recommendations, market analysis, general aviation airport demand drivers, the Maryland Aviation Administration (MAA) reports, and information from airport experts. -

GWBAA Holds Tenth Annual Safety Standdown

Facebook Twitter General Aviation Terminal, Hangar 7 Washington, DC 20001 www.gwbaa.com [email protected] May 20, 2016 GWBAA Holds Tenth Annual Safety Standdown Bob Agostino Keynotes Safety Event at NTSB Training Center Many thanks to all who attended our tenth annual safety standdown, which was held at the NTSB Training Center in Ashburn, Virginia on May 5. GWBAA also thanks our keynote speaker, Robert Agostino; our other speakers; and our sponsors, listed below. Additionally, many of our speakers kindly have made available copies of their presentations - on topics ranging from how to build a safety culture to the latest developments at the Potomac TRACON - which are available at http://www.gwbaa.com/standdown.html. 1 Regional News Round-Up A 2017 transportation funding bill introduced by Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-Md), Vice Chair of the Senate Appropriations committee, among other provisions would ensure funding for the 149 149 federal contract air traffic control towers, including five in Maryland (Easton, Frederick, Hagerstown, Martin State, and Salisbury) that previously have been under threat due to "sequestration." The Aero Club of Washington and the National Aeronautical Association have solicited nominations for the annual awards presented by the Aero Club - for the NAA's Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy (due by July 1), which honors an individual for "significant public service of enduring value to aviation in the United States," as well as the Aero Club's own Donald Engen Trophy for Aviation Excellence (due by August 31), for which both individuals and organizations/corporations are eligible. For more information, please visit both https://naa.aero/awards/awards-and-trophies/wright-brothers-memorial- trophy and http://www.aeroclub.org/awards/. -

CESSNA 152S, RENEWED P.38

TRADING FUSES FOR CIRCUIT BREAKERSp.32 March 2021 • cessnaflyer.org CESSNA 152s, RENEWED p.38 Troubleshooting a Hot Cylinder p.16 Destination: Looking for the Lone Eagle p.48 2 • Cessna Flyer / March 2021 …the heart of your aircraft® Aircraft Spruce is the leading worldwide distributor of general aviation parts and supplies. Our orders ship same day, at the lowest prices, and with the support of the most helpful staff in the industry. We look forward to our next opportunity to serve you! www.aircraftspruce.com ORDER YOUR FREE 2020-2021 CATALOG! 1000 PAGES OF PRODUCTS! Call Toll Free 1-877-4-SPRUCE March 2021 / Cessna Flyer • 3 Vol. 18 • Issue 3 • March 2021 Quality, Innovation and Performance The Official Magazine of The Cessna Flyer Association from the Brands you Trust. PRESIDENT Used Aircraft Marketplace Jennifer Dellenbusch [email protected] 1964 PIPER SUPERLIST CUB 160/L-21 YOUR • N407WB AIRCRAFTSELLING YOUR AIRPLANE? • List it here! VICE PRESIDENT/DIRECTOR OF SALES Kent Dellenbusch [email protected] ® FOR SALE CREATIVE DIRECTOR Pierre Kotze • Spark Plugs • Temperature Probes Highly Modified, Totally Rebuilt, Modeled after the L-21 Military Version • Oil Filters with Extended Wings, ailerons & flaps. Lycoming O-320 160 HP Engine ASSOCIATE EDITOR • Instruments Used Aircraft Marketplace • ONLY 141 Hours since Total Restoration • Annual Due: January Scott Kinney • Dry Air Pumps 2021 • ADS-B Out Compliant • Will DELIVER to Buyer’s Location • • Test Equipment $134,500 or $132,000 without ALASKA Bushwheels $ • Regulators -

Bay Bridge Airport (W29) Maryland Economic Impact of Airports for More Information, Please Contact

Maryland Benefits from Airports - Maryland’s economic well-being is interconnected with its vibrant airport system and its robust aviation industry. The State’s aviation system allows the community at-large to capitalize on an increasingly global marketplace. - Aviation in Maryland both sustains and leads economic growth and development. Protecting and investing in airports will support the aviation industry and sustain the industry’s positive impact on local, regional, and state economies. With continued support, Maryland’s dynamic aviation system will continue to provide a significant economic return in the years to come. - When the regional and local economic impacts of Maryland’s 34 public-use general aviation and scheduled commercial service airports (excluding Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport) are added together, over 9,900 jobs can be traced to the aviation industry. These employees receive more than $583 million in total payroll, and generate nearly $1.1 billion in total economic activity – over $867 million in business revenue and $272 million in local purchases. - The total employment numbers for Maryland’s public-use general aviation and scheduled commercial service airports includes nearly 5,000 direct jobs created by airport and visitor activity at these airports. Over 2,300 jobs were supported in local economic sectors as a result of purchases for goods and services by those 5,000 directly-employed workers; and, over 2,600 indirect jobs were supported by over $272 million of local purchases by airport tenants. - Nearly $583 million dollars in personal wages and salary income was created in the State of Maryland by the activity at these 34 airports. -

State and Local Guide to the American Rescue Plan

U.S. SENATOR BEN CARDIN'S STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT GUIDE TO THE AMERICAN RESCUE PLAN MARCH 12, 2021 U.S. SENATOR BEN CARDIN -2- MARCH 12, 2021 THE AMERICAN RESCUE PLAN ACT This guide provides an overview of funding available to state and local governments under the recently enacted American Rescue Plan Act. Where available, estimated or actual state and county level allocations of funding are provided. Page 3 - Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Page 17 - Vaccine Deployment, Testing, and Health Care Assistance Page 20 - Housing Assistance for Renters, Homeowners, and the Homeless Page 22 - Transportation Support Page 24 - Broadband Connectivity Support Page 25 - Education Funding Page 27 - Child Care Payment Support and Provider Relief Page 28 - Utility Assistance Page 29 - Direct Constituent Relief PLEASE NOTE: The funding allocations listed below include initial estimates from federal agencies and the Congressional Research Service. The actual amounts awarded to Maryland local governments may vary slightly depending on final agency interpretation and guidance. For additional guidance or clarification on the items included in this guide, please contact my staff at [email protected] for assistance. U.S. SENATOR BEN CARDIN -3- MARCH 12, 2021 CORONAVIRUS STATE AND LOCAL FISCAL RECOVERY FUNDS: MARYLAND ALLOCATION ESTIMATES Under the $360 billion Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, every level of government will receive funding, regardless of size. Funds can be utilized by state, county, and municipal governments to respond to and prepare for COVID- 19 activities, as well as the replacement of revenues lost as a result of COVID-19. All funds must be expended by December 31, 2024.