The Choking Game: Physician Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choking Game” Awareness and Participation Among 8Th Graders — Oregon, 2008

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Weekly / Vol. 59 / No. 1 January 15, 2010 “Choking Game” Awareness and Participation Among 8th Graders — Oregon, 2008 The “choking game” is an activity in which persons strangu- based on the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) and late themselves to achieve euphoria through brief hypoxia (1). It includes questions on physical and mental health, sexual activ- is differentiated from autoerotic asphyxiation 2,3( ). The activity ity, substance use, physical activity/nutrition, and community can cause long-term disability and death among youths (4). In characteristics. In 2008, all 647 Oregon public middle and high 2008, CDC reported 82 deaths attributed to the choking game schools were part of the sampling frame, which was stratified and other strangulation activities during the period 1995–2007; into eight regions. Schools were sampled randomly from within most victims were adolescent males aged 11–16 years (4). To each region, with a total of 114 schools being sampled. The data assess the awareness and prevalence of this behavior among were weighted to achieve a statewide representative sample. 8th graders in Oregon, the Oregon Public Health Division Weighting was based on the probability of school and student added a question to the 2008 Oregon Healthy Teens survey selection, and a post-stratification adjustment for county par- concerning familiarity with and participation in this activity. ticipation. Schools use an active notification/passive consent This report describes the results of that survey, which indicated model with parents, who may decline their child’s participation. that 36.2% of 8th-grade respondents had heard of the choking In 2008, the survey contained a total of 188 questions, which game, 30.4% had heard of someone participating, and 5.7% had were designed to be completed in the course of a class period. -

Autoerotic Asphyxiation: Secret Pleasure—Lethal Outcome?

Autoerotic Asphyxiation: Secret Pleasure—Lethal Outcome? WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Centuries old, AEA first AUTHOR: Daniel D. Cowell, MD, MLS, CPHQ appeared in medical literature in 1856. Etiology is speculative, Departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine and and the majority of reports deal with fatal cases. Distortions of Graduate Medical Education, Marshall University, Joan C. normal development on the basis of psychoanalytic theories are the Edwards School of Medicine, Huntington, West Virginia most prevalent understanding of the disorder. KEY WORDS asphyxiation, “choking games,” hypoxia/anoxia, lethal, WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: AEA is little known beyond forensic masochism/sadism, sexual stimulation, suffocation, suicide medicine and is generally regarded as a curiosity rather than a ABBREVIATION medical disorder whose onset is in childhood or adolescence. AEA—autoerotic asphyxiation This study adds understanding of causation and provides guidance to www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2009-0730 pediatricians on recognition and management. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0730 Accepted for publication Jun 4, 2009 Address correspondence to Daniel D. Cowell, MD, MLS, CPHQ, Departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, and Graduate Medical Education, Marshall University, Joan C. abstract Edwards School of Medicine, 1600 Medical Center Dr, Suite 3414, Huntington, WV 25701. E-mail: [email protected] OBJECTIVE: Voluntary asphyxiation among children, preteens, and ad- PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275). olescents by hanging or other means of inducing hypoxia/anoxia to Copyright © 2009 by the American Academy of Pediatrics enhance sexual excitement is not uncommon and can lead to unin- FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The author has indicated he has no tended death. -

Indian Country Issues

Indian Country Issues In Tbis Issue . Jurisdictional Conflicts Between Tribes and States: Disputes Over Land Set Aside Pursuant to the Indian Reorganization Act and July Reservation Boundary Disputes .............................. 1 2014 By Gina Allery and Darou T. Carreiro Volume62 Number4 Protecting the Civil Rights of American Indians and Alaska Natives: The Civil Rights Division's Indian Working Group ............. 10 Uniled,States By Verlin Deerinwater and Susana Lorenzo-Giguere Department of1\lstice l!!:xeeutive Office fur United States Altom.y. Wubington, DC Reentry Programming in Indian Country: Building the Third Leg 20530 of the Stool ............................................... 16 Monty Wilkinson By Timothy Q. Purdon Director Contributors' opinions and statements Native Children Exposed to Violence: Defending Childhood in should not be considered an Indian Country and Alaska Native Communities ............... 22 endorsoment by EOUSA fur any poJicy1 program, or service By Amanda Marshall Tbe United Statos Altomeys' Bulletin is published plll'$uant to Investigating and Prosecuting the Non-Fatal Strangulation Case .. 28 28 CFR § 0 22(b) By Leslie A. Hagen Tbe United StaleS Altornoys' Bulletin ;. publilbed bJmonthly by the Executive Office fur United States Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act Attorney., Offico ofLegall!dueation, 1620Pendleto.IIStreet, (NAGPRA): The Law Is Not an Authorization for Disinterment . .41 Columbia, Seulh Carolina 29201 By Sherry Hutt and David Tarler Manaatn~ Editor The Investigation -

Phs 403 Accident and Emergency

COURSE GUIDE PHS 403 ACCIDENT AND EMERGENCY Course Team Dalyop .D.Mancha (Course Developer/Writer) - CHT, Pankshin Dr. Gideon I.A. Okoroiwu Ph.D. (Course Reviewer) - NOUN NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA MAIN CONTENT CONTENTS PAGE Module 1 Accidents and Emergency ………… 1 Unit 1 Introduction…………………………. 1 Unit 2 Accidents…………………………… 5 Unit 3 Emergency Medical Services(Ems) Systems………………… 13 Module 2………………………………………… 24 Unit 1 Fall Related Injuries…………………… 24 Unit 2 Drowning…………………………….. 28 Unit 3 Stress…………………………………. 35 Unit 4 Physiology of Stress………………… 46 Unit 5 Anxiety, Death and Dying…………… 52 Module 3 Emergency Conditions(I)………….. 63 Unit 1 Violent Injuries……………………… 63 Unit 2 Poisoning……………………………. 67 Unit 3 Fluid And Electrolytes…………….. 83 Module 4……………………………………… 91 Unit 1 Shock……………………………….. 91 Unit 2 Cardiac Attack/Arrest……………… 103 Unit 3 Haemorrhage………………………… 135 Unit 4 Behavioural And Psychiatric Emergency…………………………… 143 Module 5 Common Emergency Conditions…….. 151 Unit 1 Head Injury………………………….. 151 Unit 2 Fracture……………………………….. 162 Unit 3 Pathogenesis of Infectious Diseases……………………………… 170 Unit 4 Emergency Respiratory Condition….. 178 Module 6…………………………… 190 Unit 1 Wound……………………… 190 Unit 2 Metabolic Emergency Diabetes… 195 Unit 3 Peptic Ulcer …………………… 201 Unit 4 Peritonitis……………………… 211 PHS 403 MODULE 1 MODUL E1 ACCIDENTS AND EMERGENCY Unit 1 Introduction Unit 2 Accidents Unit 3 Emergency Medical Services Systems UNIT 1 INTRODUCTION 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Objectives 3.0 Main Content 3.1 Definition of A&E 3.2 Triage 3.3 Resuscitation Area 3.4 Play Therapist 4.0 Conclusion 5.0Summary 6.0 Tutor-Marked Assignment 7.0 References/Further Reading 1.0 INTRODUCTION This is also known as emergency department(ED),Emergency Room (ER), or Casuality Department. -

Autoerotic Asphyxia and Asphyxial Games As Part of the Same Syndrome Andrés Rodríguez Zorro

Unintentional Asphyxial Deaths in Adolescence Autoerotic Asphyxia and Asphyxial Games as Part of the Same Syndrome Andrés Rodríguez Zorro William Harvey Research Institute MSc in Forensic Medical Sciences Unintentional Asphyxiation Deaths in Adolescents: Autoerotic asphyxia and asphyxial games as part of the same syndrome Forensic Pathology Andrés Rodríguez Zorro Student ID: 100511332 Monday, September 3th, 2012 Supervisor: Professor Peter Vanezis Word count: 19.575 Dissertation submitted to Queen Mary University of London in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree Beneficiario Colfuturo 2011. Unintentional Asphyxial Deaths in Adolescence Autoerotic Asphyxia and Asphyxial Games as Part of the Same Syndrome Andrés Rodríguez Zorro CONTENTS LISTE OF TABLES 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 4 1.0 ABSTRACT 5 2.0 METHOD OF UNDERTAKING THE LITERATURE SEARCH 6 3.0 INTRODUCTION 7 3.1 Definition of autoerotic asphyxia 7 3.2 Definition of asphyxial games 8 3.3 History 9 3.4 Neurophysiology of neck compression asphyxias 12 3.5 Characteristics of autoerotic asphyxiation 16 3.6 Characteristics of asphyxial games 18 3.7 Aims 21 4.0 RESULTS 4.1 Who plays asphyxial games 23 4.2 Who are the victims of autoerotic asphyxia in general population 28 4.3 Who are the victims of autoerotic asphyxiation in adolescence 32 4.4 Who are the victims of asphyxial games 36 4.5 Comparative analysis of asphyxial games and autoerotic asphyxia 41 5.0 DISCUSSION 5.1 Etiologic theories 44 5.2 Sociological view: the ordeal or radical confrontation with death 46 5.3 Confrontation with risk in adolescence 48 5.4 Childhood rope syndrome 51 5.5 Part of same syndrome 52 5.6 Risk of death 61 5.7 Limitations 63 5.8 Recommendations 65 6.0 REFERENCES 67 Beneficiario Colfuturo 2011. -

The Year Michael Got His Own Page in the Yearbook by Nick Seagers

The Year Michael Got His Own Page in the Yearbook by Nick Seagers Some kids use a belt or a length of rope. Some kids use a dog leash. My brother, Michael Foley, chose to use a guitar strap looped over the metal track of the garage door. It was raining the day I opened that door and found him. One of his hands was caught between the strap and his neck, like he tried to change his mind too late. This was back when I was a sophomore and still thought life was something that was more ahead of me than behind me. What Michael did is sometimes mistaken for suicide. What we all learned is that it's really called Thrill Asphyxiation but you could call it Space Monkey or The Choking Game or Black-Out if it makes you more comfortable. Hundreds of kids die each year from it, but not many parents knew about it. After some investigations were done, the statistics showed some fourteen other teenagers died the same way in Vernon. You can use your shoelaces or an Ace bandage. Loop a belt around your neck and toss the loose end over a shower curtain or closet pole. Pull. Try to lift yourself off the ground. aitW until your vision gets starry and starts to shut down. Your face will get red and hot and you should be able to feel your pulse in your eyes. Now, let go. When the pressure is released, the blood flowing back into the brain creates a rush. -

The Choking Game

The Choking Game • Hatim Omar, MD • Professor, Pediatrics, Obstetrics/Gynecology • Chief, Division of Adolescent Medicine • KY CLINIC, Rm. J422, University of Kentucky • Lexington, KY 40536-0284 • Tel. 859-323-5643, Fax. 859-323-3795 or 859- 257-7706 • Email: [email protected] DISCLOSURE I have no relevant financial relationships with the manufacturers of any commercial products and/or provider of commercial services discussed in this CME activity Objectives • Definition and epidemiology of the choking game • Why is it done • Consequences • Prevention Craig Morse Blake Edward Conant 16 Tyler 15 Griffin 12 Randall Stamper 12 Kyle O’Connor 12 Jenny Morgan Alesa Beth 17 Uriah Martin Somers 12 13 In loving memory of Jack Henry Evans November 11, 1995 - July 10, Also known as: PASSOUT SPACE MONKEY Adolescent Development • Puberty • Adolescence • Vulnerability • Risk Behaviors • Behavior Change • Positive Youth Development PUBERTY VS ADOLESCENCE • Humans have the longest puberty and adolescence of all primates • Mean length of puberty is 4 years in Western cultures • Length of adolescence is variable and may last a lifetime PUBERTY VS ADOLESCENCE • Puberty is the biological process of change while adolescence is the psychosocial concomitants • They are usually interdependent but not always so • Marketing of clothing, behaviors and activities may precipitate ‘prepubescent’ adolescence PUBERTY VS ADOLESCENCE • Both puberty and adolescence are periods of rapid change and therefore easily influenced by environmental factors both positive and negative -

ENA Topic Brief

ENA Topic Brief Key Information An Overview of Strangulation The detection of strangulation and its effects on a patient can Injuries and Nursing be challenging for emergency nurses despite their level of skills and expertise.1,2 Implications Strangulation can occur with Purpose very little pressure to the neck, therefore physical signs and The detection of strangulation and its effects on a patient can be challenging for symptoms are not always emergency nurses despite their level of skills and expertise.1,2 Strangulation can obvious and can easily be occur with very little pressure to the neck, therefore physical signs and missed by healthcare providers.1 symptoms are not always obvious and can easily be missed by healthcare The incidence of strangulation, providers.1 The patient may not report that strangulation occurred for various in particular, hangings, has reasons, making evaluation of these patients more difficult. Having an index of increased in the United States suspicion for strangulation during the assessment may help detect these injuries and worldwide.3 when they are insidious.1 The incidence of strangulation, particularly hangings, The primary mechanisms of has increased in the United States and worldwide.3 While the emergency nurse is strangulation are hanging, prepared to manage airway obstructions and hypoxia, he or she may have ligature strangulation, and limited understanding of the complexities surrounding strangulation, including manual strangulation.5 assessment, signs and symptoms, nursing implications, and other challenges such Near-hangings and accidental as those associated with intimate partner violence (IPV), risky personal hangings are rare but do occur behaviors, forensic evidence collection, and suicide. -

Umatilla February, 2018

2017 Umatilla February, 2018 Contacts for More Information and Help Interpreting Results Isabelle Barbour, MPH Your questions, concerns and comments are invited. For more information or help Policy Officer with questions, please contact: 800 NE Oregon St., Suite 825 Portland, OR 97232 Renee Boyd Phone: 971-673-0376 j Email: [email protected] OHT Survey Coordinator Program Design and Evaluation Services Public Health Division Duyen Ngo, PhD, MPH 800 NE Oregon St., Suite 260 Surveillance Technical Lead Portland, OR 97232 Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Phone: 971-673-1145 j Email: [email protected] Public Health Division Phone: 971-673-1024 j Email: [email protected] Ely Sanders, MPA Sexual Health and School Health Educator Survey services provided by: Oregon Department of Education Office of Learning International Survey Associates (ISA) d/b/a Pride Surveys Student Services Unit Jay Gleaton, President/CEO Phone: 503-947-5904 j Email: [email protected] 2140 Newmarket Pky. SE Suite 116 Marietta, GA 30067 Wes Rivers, MPAff Phone: 1-800-279-6361 j Email: [email protected] Adolescent Health Policy & Assessment Specialist Adolescent and School Health Program 800 NE Oregon St., Suite 805 Portland, OR 97232 Phone: 971-673-0267 j Email: [email protected] Contents 9 GAMBLING 53 1 INTRODUCTION 16 10 SEXUAL BEHAVIOR 55 1.1 Overview................................ 16 1.2 Health and Learning.......................... 16 11 SEXUAL COERCION, SEXUAL ASSAULT AND INTIMATE 1.2.1 How Are OHT Survey Results Used?............. 16 PARTNER VIOLENCE 57 1.3 Survey Methodology......................... -

The Investigation and Prosecution of Strangulation Cases

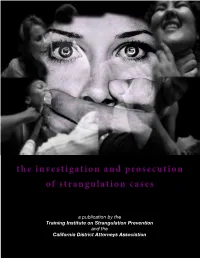

the investigation and prosecution of strangulation cases a publication by the Training Institute on Strangulation Prevention and the California District Attorneys Association He woke up and I saw stars and I passed immediately started out. When I came to, he’s on “ “top of me, banging my head choking me and put me up against the kitchen floor against the wall. I fell and and strangling me.” urinated on myself. Right — Reena after I hit him he let go from choking me and he started punching me on the floor.” I was trying to get away and he grabbed me, spun me around, started to choke me, brought me — Julie “ down to the ground, and at the same time that he was trying to— Jan choke me, he was trying to slam I would always remember my head on one of the rocks.” soreness and bruises on my neck. [My neck] would be sore for at “ least four or ve days.” The very first time he — Survivor was violent with me he strangled me. He “pushed me up against a wall. He held his Actually, when I came out of that hands on my throat [strangulation incident], I was more and had me pinned submissive. More terrified that the next against the wall with “ time I might not come out—I might not my feet in the air. At make it. So I think I gave him all my that moment I really power from there, because I could see thought he was going how easy it was for him to just take my to kill me.” life like he had given it to me.” — Lana — Ruth © 2013. -

Non-Fatal Strangulation Documentation Toolkit

Non-Fatal Strangulation Documentation Toolkit International Association of Forensic Nurses www.ForensicNurses.org November 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface i Strangulation Task Force Members 1 Purpose 3 Section I – Non-Fatal Strangulation Strangulation Assessment, Documentation, and Evidence Collection Guidelines 4 Section II – Non-Fatal Strangulation Policy and Procedure Example Policy and Procedure 7 Section III – Clinical Evaluation and Documentation Non-Fatal Strangulation Clinical Evaluation 9 Non-Fatal Strangulation Descriptors for Examiners 11 Non-Fatal Strangulation Documentation Form 14 Section IV – Discharge Instructions Example Strangulation Discharge Instructions 21 Additional Resources 22 References References 23 Bibliography Comprehensive Bibliography 25 PREFACE In 1992, The International Association of Forensic Nurses (IAFN) was created by a group of nurses that recognized violence as a healthcare problem. Over the past two and a half decades much progress has been made as it relates to the care of our specialized patient population. Through this progress, knowledge has been gained and practice guidelines continue to evolve with the goal of continuous provision of safe and effective patient care. In early 2015, the IAFN, the Board of Directors and a group of members recognized strangulation as a healthcare concern that needed practice guidance throughout the organization, and as a result, the Strangulation Task Force was created and was proven to be a group of hard working, dedicated individuals that are truly experts on strangulation. This group was tasked with establishing standards for the organization and developed what would be utilized as a toolkit for best practice provision. The Strangulation Toolkit provides the forensic nurse with detailed guidance on assessment techniques, documentation, and evidence collection for this patient population. -

Adolescent Mental Health and the Choking Game

Adolescent Mental Health and the Choking Game Grégory Michel, PhD,a Mathieu Garcia, MPhil,a Valérie Aubron, PhD,b Sabrina Bernadet, PhD,c Julie Salla, PhD,a Diane Purper-Ouakil, MD, PhDd OBJECTIVES: To examine the demographic and health risk factors associated with participation in abstract the choking game (CG), a dangerous and potentially fatal strangulation activity in which pressure is applied to the carotid artery to temporarily limit blood flow and oxygen. METHODS: We obtained data from 2 cross-sectional studies realized respectively in 2009 and 2013 among French middle school students. The 2009 (n = 746) and 2013 (n = 1025) data sets were merged (N = 1771), and multivariate modeling was conducted to examine demographic and clinical characteristics of youth reporting a lifetime participation in the CG. The 2 studies included questions about risk-taking behaviors and substance use, and standardized assessments were used to collect conduct disorder symptoms and depressive symptoms. RESULTS: In the merged 2009 and 2013 data set, the lifetime prevalence of CG participation was 9.7%, with no statistically significant differences between boys and girls. A multivariate logistic regression revealed that higher levels of conduct disorder symptoms (odds ratio: 2.33; P , .001) and greater rates of depressive symptoms (odds ratio: 2.18; P , .001) were both significantly associated with an increased likelihood of reporting CG participation. CONCLUSIONS: The significant relationship between elevated levels of depressive symptoms and participation in the CG sheds new light on the function of self-asphyxial activities. However, with the finding that higher rates of conduct disorder symptoms were the most important predictor of CG participation, it is suggested that the profile and the underlying motivations of youth who engage in this activity should be reexamined.