North West Geography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Ruskin 2009-10

JOHN RUSKIN SCHOOL Travel Plan MARCH 2010 CONTENTS PAGE CONHEADING TITLE PAGE 1 School details 3 2 Location and use of school 4-6 3 Current transport situation and 7-8 transport links 4 Aims and objectives 9 5 Working party and consultation 10 6 Survey and route plotting 11-18 7 What we already do 19 8 Summary of road and transport 20 problems 9 Working party 21 recommendations for action 10 Targets – specific % targets for 22 modal shift 11 Action plans 23-26 12 Review of targets 27 13 Cycle count 28 14 Monitoring training 28 Signed agreement APPENDICES Passenger transport map 1 Online student and staff survey results 2 Route plotting maps 3 Accident data 4 Minutes/correspondence 5 JOHN RUSKIN SCHOOL TRAVEL PLAN 2010 Page 2 1 School details DCSF school reference number 9094151 Type of school Community Secondary Number on roll (including no. of SEN students with a brief description of subsequent 199 impact on travel) Number of staff (It is highly recommended that a supplementary 32 Travel Plan for staff and other school users is developed) Age range of students 11-16 School contact details Head teacher Mrs Miriam Bailey John Ruskin School Lake Road Address Coniston Cumbria Postcode LA21 8EW Telephone number 01539 441306 Email address [email protected] Website www.jrs.org.uk School Travel Plan Coordinator Helen Tate Contact [email protected] JOHN RUSKIN SCHOOL TRAVEL PLAN 2010 Page 3 2 Location and use of school Location of school Our school is an 11-16 school at the heart of the Lake District. -

Langdale Campsite N

To Old Dungeon To Sticklebarn / Ghyll Hotel Ambleside / Grasmere Take a bike ride... Welcome to bike hire available Langdale Campsite N Great Langdale Campsite 139 entrance & exit 138 141 137 142 140 Check in at reception 136 Welcome to Langdale! Group Field 134 Local food and beer 130 135 129 132 to sample at Sticklebarn 133 131 165 127 128 164 163 166 162 161 160 168 High views & wild places... 159 169 167 Dungeon Ghyll 158 170 access to Langdale Pikes, Stickle Ghyll/Tarn, Blisco 171 174 157 173 175 172 Bowfell and Blea Tarn walks from site. 176 181 178 Get maps and advice from the shop. 2 156 183 8 3 Reception Playground 177 9 179 14 180 15 4 190 182 24 1 Crinkle Crags 189 184 25 10 7 207 185 General site information 33 13 186 Family Field 34 5 206 187 35 16 Bowfell 188 199 43 23 12 6 198 44 26 197 • Make sure tents are at least six metres apart 52 32 196 53 36 22 17 11 (approximately seven paces) 54 42 27 First-Come-First- 195 45 194 205 21 204 37 31 18 Served Field • Please be quiet, especially from 11pm-7am, and be To Old 203 Main Field 51 28 41 20 19 considerate of other campers Dungeon Ghyll 202 46 Access to 50 38 30 (on foot) 201 29 • Help us keep the site clean by using the bins and 49 40 footpath to 200 56 57 48 39 White Ghyll recycling points provided 59 Elterwater 47 Gimmer Crag 58 Stickle Ghyll • Fires are only allowed if they are contained and 120 raised off the ground To Blea Tarn / 119 Lingmoor Little Langdale 118 Side Pike • Well behaved dogs on leads are welcome so long as they are cleared up after 121 61 60 122 64 123 • Parking on hard standing only New Field 67 Key 62 63 66 If you have any problems during your stay, please tell (seasonal) 68 Biomass boiler 69 Small pitches Toilets a member of staff and we will do our best to help. -

The English Lake District

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues La Salle University Art Museum 10-1980 The nE glish Lake District La Salle University Art Museum James A. Butler Paul F. Betz Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation La Salle University Art Museum; Butler, James A.; and Betz, Paul F., "The nE glish Lake District" (1980). Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues. 90. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues/90 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the La Salle University Art Museum at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T/ie CEnglisti ^ake district ROMANTIC ART AND LITERATURE OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT La Salle College Art Gallery 21 October - 26 November 1380 Preface This exhibition presents the art and literature of the English Lake District, a place--once the counties of Westmorland and Cumber land, now merged into one county, Cumbria— on the west coast about two hundred fifty miles north of London. Special emphasis has been placed on providing a visual record of Derwentwater (where Coleridge lived) and of Grasmere (the home of Wordsworth). In addition, four display cases house exhibits on Wordsworth, on Lake District writers and painters, on early Lake District tourism, and on The Cornell Wordsworth Series. The exhibition has been planned and assembled by James A. -

Duddon Valley - Eskdale Drive

Coniston - Duddon Valley - Eskdale drive A drive that includes the most challenging mountain pass roads in the Lake District along with some remote and beautiful scenery. The drive also visits a number of historic attractions and allows a glimpse of bygone industry in the area. Eskdale Railway, Dalegarth Route Map Summary of main attractions on route (click on name for detail) Distance Attraction Car Park Coordinates 0 miles Coniston Village N 54.36892, W 3.07347 0.8 miles Coniston Water N 54.36460, W 3.06779 10.5 miles Broughton in Furness N 54.27781, W 3.21128 11.8 miles Duddon Iron Furnace N 54.28424, W 3.23474 14.5 miles Duddon Valley access area N 54.31561, W 3.23108 21.7 miles Forge Bridge access area N 54.38395, W 3.31215 23.7 miles Stanley Force waterfall N 54.39141, W 3.27796 24.1 miles Eskdale Railway & Boot N 54.39505, W 3.27460 27.5 miles Hardknott Roman Fort N 54.40241, W 3.20163 28.2 miles Hardknott Pass N 54.40290, W 3.18488 31.6 miles Wrynose Pass N 54.41495, W 3.11520 39.4 miles Tilberthwaite access area N 54.39972, W 3.07000 42.0 miles Coniston Village N 54.36892, W 3.07347 The Drive Distance: 0 miles Location: Coniston Village car park Coordinates: N 54.36892, W 3.07347 The village of Coniston is in a picturesque location between Coniston Water and The Old Man of Coniston, the mountain directly behind. The village has a few tourist shops, cafes, pubs and access to some great walking country. -

Little Langdale Rydal and Skelwith Bridge Traffic Regulation Order

The County of the County of Cumbria (various roads, South Lakeland area )(consolidation of Traffic regulations) (order 2002) (Little Langdale, Rydal and Skelwith Bridge) variation order 2021 1. The Cumbria County Council hereby give notice that on 6 July 2021 it made the above Order under Sections 1(1), 2(1) to (4), 19, 32, 35, 35A, 38, 45, 46, 47, 49, 51, 53 and 64 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984. 2. The Order will come into operation on 12 July 2021 and its effect will be to introduce “No Waiting At Any Time”, ie double yellow line restrictions on parts of the following: - (i) the U5527, U5529 and U5531 Little Langdale; (ii) the A591 Rydal; and (iii) the A593, B5343 and U5738 Skelwith Bridge. 3. Full details of the Order, together with a plan showing the lengths of road concerned, and a statement of the Council's reasons for making the Order, may be viewed on the Council’s website using the following link: - https://www.cumbria.gov.uk/roads-transport/highways- pavements/highways/notices.asp and may otherwise be obtained by emailing [email protected] . 4. If you wish to question the validity of the Order or of any provision contained in it on the grounds that it is not within the powers conferred by the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 or on the grounds that any requirement of that Act or any instrument made thereunder has not been complied with in relation to the Order, you may within six weeks of 6 July 2021 apply to the High Court for this purpose. -

4-Night Southern Lake District Guided Walking Holiday

4-Night Southern Lake District Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: CNBOB-4 2, 3 & 5 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Relax and admire magnificent mountain views from our Country House on the shores of Conistonwater. Walk in the footsteps of Wordsworth, Ruskin and Beatrix Potter, as you discover the places that stirred their imaginations. Enjoy the stunning mountain scenes with lakeside strolls, taking a cruise across the lake on the steam yacht Gondola, or enjoy getting nose-to-nose with the high peaks as you explore their heights. Whatever your passion, you’ll be struck with awe as you explore this much-loved area of the Lake District. HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Head out on guided walks to discover the varied beauty of the South Lakes on foot • Choose a valley bottom stroll or reach for the summits on fell walks and horseshoe hikes • Let our experienced leaders bring classic routes and hidden gems to life • Visit charming Lakeland villages • A relaxed pace of discovery in a sociable group keen to get some fresh air in one of England’s most beautiful walking areas www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • Evenings in our country house where you can share a drink and re-live the day’s adventures TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 2, 3 and 5. Our best-selling Guided Walking holidays run throughout the year - with their daily choice of up to 3 walks, these breaks are ideal for anyone who enjoys exploring the countryside on foot. -

# # # # # # Æ Æ Æ Æ Æ Æ Æ Æ # ÷ # # # # Æ Æ Æ

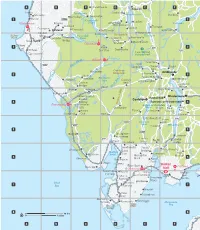

#\ A B C #\ Thackthwaite D #\ E F Keswick Lowca Swinside #\ #\ #\ Loweswater #\ Moresby Derwentwater Dockray #\ Lamplugh #\ Loweswater 1 #\ Parton 0¸A5086 1 Crummock #\ #\ #\ Lodore Whitehaven Rowrah Water Little Town Ullswater #\ Brackenburn #æ] #\Kirkland #\Thirlspot \# Frizington #\ Grange 1 #\ Kirkland Croasdale \# Buttermere Glenridding #\ 0¸B5345 Cleator #\ Watendlath St Bees #\ Buttermere Borrowdale Moor #\ Ennerdale Thirlmere Head #\ Parkside Ennerdale Water #\ Gatesgarth #\Rosthwaite #\ Bridge 3 0¸B5289 Moor Row \# #\ Stonethwaite Ennerdale #æ Seatoller St Bees # 2 #\ 2 Head Black #÷ 0¸A591 # #\ St Bees Sail YHA Seathwaite 0¸A592 Lake District Egremont #\ National Park ng Wasdale #æ#\ 2 Ble Grasmere r #\ 0¸A595 ve Great Ri Chapel Rydal Langdale #\ # #\ Stile Wastwater Cumbrian #\ n #\ Ambleside e Mountains Elterwater 3 h #] 3 E #\ Nether Skelwith Bridge#\ r Burnmoor k #\ #\ e #\ Wasdale s Waterhead v Gosforth Tarn Cockley i E Little Langdale R Santon er Beck \# Troutbeck #\ Bridge iv R Bridge Seascale#\ #\ Boot #\ y High Wray #\ Irton Eskdale e #\ l \# l Holmrook #\ a V #] #Ravenglass & #\ Windermere #\ on Hawkshead Eskdale d Coniston #] d #\ 4 Railway u Bowness-on-Windermere 4 #\ D #æ # Muncaster #\ Ravenglass 4 #\ Esthwaite Grizedale #\ Castle Seathwaite Water Forest Near Ferry #\ Broad Torver Grizedale #\ Sawrey Nab #\ #\ Lane End #\ Oak Ulpha#\ Winster #\ Satterthwaite Force 0¸A592 0¸A593 Coniston #\ Mills Water 0¸A595 Rusland Windermere #\ 5 5 0¸A5084 #\ Bootle Broughton- #\ #\ in-Furness Lakeside 0¸A595 Lowick Bouth #\ -

5-Night Southern Lake District Guided Walking for Solos Holiday

5-Night Southern Lake District Guided Walking for Solos Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Holidays for Solos Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: CNBOS-5 2, 3 & 5 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW A Guided Walking holiday based in the National Trust’s historic Monk Coniston Hall, overlooking Coniston Water. It's the ideal way to explore the beautiful lakes and mountains in the Lake District National Park and meet other solo travellers. Enjoy a choice of guided walks day to make the most of the area and to get to know your fellow walkers. WHAT'S INCLUDED • Full Board en-suite accommodation in our country house. There's no extra charge for single rooms • A full programme of walks with all transport to and from the walks, and light-hearted evening activities • Choose from up to 3 guided walks each walking day, with expert guides • Relax in our Gothic-style country house with its lakeside location and glorious views • We pride ourselves on the social atmosphere of our holidays - walk together, eat together and relax together www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Ascend mountain summits in the Southern Lake District • Walk by lakes and tarns and visit the Lakeland stone villages • Discover the area’s literary connections with William Wordsworth, Arthur Ransome, John Ruskin and Beatrix Potter • Walk past abandoned copper mines and slate quarries, now blending into the landscape, evidence of Lakeland’s rich industrial past TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 2, 3 and 5, Explore the very best of the Lake District on our guided walks. -

Walking Weekend – Borrowdale, the Lake District

Walking Week 2019 Coniston Water South Lakes Date: Saturday 1 to Saturday 8 June 2019 (7 nights) Place: Monk Coniston, Coniston Water, LA21 8AQ Cost: £625.00 en suite per person in a single room £525.00 en suite per person in a shared twin / double room Included: 7 nights’ accommodation, 7 breakfasts, 7 picnic lunches, 7 evening meals & 5 days of guided walks and one free day to explore the area Extras: local transport (if used) Places: 20 (en-suite 8 single rooms, 3 twin rooms and 3 double rooms) Overview: We are seriously looking forward to visiting the National Trust country house property named Monk Coniston. It commands spectacular views down to Coniston Water and its idyllic location allows us get the very best out of this belting walking area. With excellent walking days planned we aim to explore some of the higher and lower fells, valleys and lakes, villages and hamlets in order to experience everything that Lakeland has to offer. From the fine high fells with open moorland and panoramic views, to the low-level field systems laden with dry-stone walls and quaint Lakeland farm; from the fast-flowing rivers replete with tumbling ghylls; from hidden away gems like Tarn Hows to the great body of Coniston Water and all this without even mentioning the fine white-washed cottages and the warm, friendly country pubs with real fires and real ales! The WalkWise Walking Programme: The beauty of this area is that we have stunning walking immediately from our doorstep, in fact some days we will be able to walk out directly from the front door which will allow us to walk everything the Coniston area has to offer. -

Liebel CJ T 2021.Pdf (405.9Kb)

Dorothy Wordsworth’s Distinctive Voice Caroline Jean Liebel Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In English Nancy Metz Peter Graham Ashley Reed May 11, 2021 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Dorothy Wordsworth, William Wordsworth, Romanticism, Grasmere Journal, Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland, environmental ethos Dorothy Wordsworth’s Distinctive Voice Caroline Jean Liebel ABSTRACT The following study is interested in Dorothy Wordsworth’s formation of her unique authorial identity and environmental ethos. I attend to her poetry and prose, specifically her journals written at Grasmere and her Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland (1874) to demonstrate how she shaped her individual voice while navigating her occasionally conflicting roles of sister and writer. My project begins with a chapter providing a selective biographical and critical history of Dorothy Wordsworth and details how my work emerges from current trends in scholarship and continues an ongoing critical conversation about Dorothy Wordsworth’s agency and originality. In my analysis of Dorothy’s distinct poetic voice, I compare selections of her writing with William’s to demonstrate how Dorothy expressed her perspectives regarding nature, community, and her place within her environment. In my chapter on Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland, I analyze the ways in which Dorothy’s narrative embraces the tenets of the picturesque while simultaneously acknowledging the tradition’s limitations. Her environmental perspective was inherently rooted in domesticity; the idea of home and her community connections influenced how she engaged with and then recorded the environments she traveled to and the people she met. -

Pinfold Listings. Condition: C = Complete Or Substantially Complete; P = Partial Remains and Recognisable; S = Site Only Identified; NF = Site Not Found

Pinfold Listings. Condition: C = Complete or substantially complete; P = Partial remains and recognisable; S = Site only identified; NF = Site not found. Ordnance Survey grid reference X and Y coordinates given. For a 6 digit grid reference read 317391, 5506847 as 173506. Or enter 12 digit reference as shown in www.old-maps.co.uk or www.streetmap.co.uk Location & Description. C Abbey Town Pound, Wigton. Grid ref: 317391,5506847 It is located on the left approaching Abbey Town from the south on the B5302, at the far end of a row of terraced houses. This is a stone pound with triangular capping stones and a small iron gate with overhead lintel. In good order, now used as a garden and approx. 10mtrs by 7mtrs. The south corner has been removed and wall rebuilt probably to give rear access to the row of houses. It is shown on the 1866 OS 1:2500 map, as a pound in the corner of a field. No buildings are shown. A date stone on the adjacent row of houses indicates they were built in 1887 and the removal of the south corner of the pinfold probably occurred then. S Ainstable Pinfold, Penrith. No trace. Grid ref: 352581,546414. Shown as a Pinfold on the 1868 OS 1:10,560 map. The road has been widened at the site and the pinfold has been lost. NF Ambleside. No trace. Grid ref: 337700,504600. Possible site is where Pinfold Garage is now built. No trace found on OS maps. S Anthorn Bridge Pinfold, Wigton. No trace. -

The Petzl Lake District Mountain Trial

The La Sportiva Lake District Mountain Trial th Sunday 10 September 2017 Fell Running from Gatesgarth Farm, Buttermere Starting at 8.30 a.m. Finishers returning from approximately 12.30 p.m. SPONSORED BY TRIAL ORGANISATION The trial is organised by the Lake District Mountain Trial Association. Our Honorary Life Vice President is John Nettleton. COMMITTEE Edwin Coope (President) Tony Richardson (Chairman) Miriam Rosen (General Secretary) Anne Salisbury (Membership & AGM Secretary) Ann Smith (Treasurer) Wendy Dodds Dave Fenwick(Course Controller ) Mike Hind (Course Planner) David & Miriam Rosen (Organisers) Dick Courchee (Organiser on the day) Tim Goffe (Control Marshals) Geoff Clarke VENUE and TRAVEL Gatesgarth Farm Buttermere. Grid Reference NY 193149 Nearest Postcode CA13 9XA* GPS 54.523587,-3.247053. The entrance will be signed. Note that the Newlands pass road over to Buttermere will be closed for roadworks. In any case we suggest you avoid Buttermere village as the Buttermere Triathlon and Open Water Swim are taking place this weekend. You are strongly advised to approach via Borrowdale and over Honister pass. * The postcode is centred near Buttermere village but Gatesgarth Farm is at the South-East end of the lake. Page 1 If you bring a dog with you, it must remain on a lead at all times. Parking is in a flat field. The parking marshals will collect £2 per car. Please have the correct change ready. THE 63rd LAKE DISTRICT MOUNTAIN TRIAL This year is the 63rd running of the Lake District Mountain Trial. A 60 year supplement to the 50 years running booklet has been prepared by Edwin Coope and some copies will be available at the Trial.