“A Little Boat Goes a Long Way”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2000-A Snips

Spring 2000 The Trailer Sailors Association Notes and Announcements 2 Trailer/Sailor s Association Information . ... ... 2 President s column ... .... .Wayne Bell 2 Errata from past issues . ... 3 North Channel Cruise Announcement ... .John Clement 3 Note on Priority Mail ..David Craigie 4 Treasurer s Report ... David Craigie 4 Flags and Tee Shirts Announcement .. 5 Trailer Sailor Web Discussion Board ...John Coppedge 5 Trailer Sailors Need Help in Florida ...David Craigie How-to Articles 6 Gizmos, Gadgets, and Galley ...ed. Debbie Bell 7 Think Alcohol Stoves are Hazard-Free? ....Ray R. Davidson 7 Cushion Tip ..Bob Brennan 8 Managing Your H2O While Cruising ..David Craigie Cruising Articles 9 Before I Get Old ... ....Rita Thomas 10 Cruising with George and George ...Larry McComb 12 The Diagonal Alternative ...Bill Atkins 15 Things to do In, On, and Around Lake Erie ..Alan Reichert 16 Summer 1998 Around Lake Huron (almost)-Part 2 ...Henk Vanderhulst 19 Pacific Coast Cruising Adventure Aboard our Bayfield 25 .Rod & Karen Duncan 20 Three Swans in the Pacific Northwest ....Carol Kulish 25 Lake Superior Cruise 1999 .Jack Johnson 27 Charleston, SC to Savannah, GA via the ICW .Max & Mandy Miller 31 McGregor Bay ..Wayne Bell 34 A Fall Cruise of the Southern Chesapeake . ...Guy Hubbard 33 Classified Ad . 38 Cruise and Gathering Announcements .. 39 Editor s Last Word ... ..Mike Nelson 40 Membership Application ... The authors of the newsletter disclaim any and all responsibility for any kind of injury or damages sustained which may result from the application of any or all ideas or suggestions appearing in any articles of Clipper Snips. -

Ff 10 03.Pdf

Contents Another Photo Issue? Contents ....................................... 2 Another Photo Issue? .................. 2 Tom Davison Flicka Owner’s Manual? ............ 3 Tom Davison About Flicka Friends .................. 3 The Annual Repainting of MARITIME’s Hull ..................... 4 Shin Kurato DART’s Voyage: Exploring The Canals of Canada ................ 6 Gill Outerbridge Our First Overnight Crossing Aboard s/y KARA DU ................ 8 Brian and Ruth Eklund Sailing to Power Island ............... 10 Tom Davison Flicka Profile: s/y PASSAGES ... 14 Tom Davison Flicka Bow Pulpits ...................... 18 Hal DeVaney Next Issue... BEN MAIN, Jr. docked after a three hour trip on Lake Michigan. The files are empty! Photo: Tom Davison © 2005 If you have an article or images, please let me know. By Tom Davison photographs of Flickas in California, Florida, Illinois, New Jersey, Maine, How about another Flicka Photo How about another photo issue of Maryland, Utah, Washington, Wiscon- Issue? The last one was in 1998. Flicka Friends? If you have a digital sin, British Columbia, and South Af- image of your Flicka on your favorite rica. cruising waters, please send me a copy for the next issue. With the explosion I live in farm country and have dial-up of digital cameras lately, I would sus- internet service. If you send more than pect there are more than a few digital a few images, please use more than one Cover Photo Flicka images laying about hard drives e-mail. Please include a caption about across the country and even the world. the scene including location along with FRONT COVER the basic information about your Flicka s/y DART docked on the The last photo issue was the Winter Flicka, such as year, boat name, hull Hudson River in Yew York. -

Flicka Friends April 2014 Issue # 58

Flicka Friends April 2014 Issue # 58 Surviving Hurricane Ike Flicka Friends 1 FLICKA FRIENDS C ONTENTS Contents ............................................... 1 The Spring Issue Is Here! The Spring Issue is Here ................. 2 A Hell of a Story ................................. 3 About Flicka Friends ......................... 3 Flicka Articles Yachts ................................................ 22 Tom Davison Flicka Building RED RASCAL, Part 5 of 12 ............... 6 Bob Collier Flicka Cruising Island Hopping Off Seattle .......... 4 Joshua Wheeler Flicka Maintenance New Handrails For ZANZIBAR .. 20 Randy Richardson Flicka Photo Gallery BLUE SKIES .................................... 16 Tom Davison ENTERPRISE .................................. 15 Hal DeVaney KITTIWAKE .................................... 15 Hal DeVaney OUTBOUND ..................................... 15 Hal DeVaney SARNIA ............................................. 17 Nat Burgess SWAN ................................................ 18 Doc Holub ZANZIBAR ........................................ 19 Randy Richardson Flicka Storm Stories Surviving Hurricane Ivan ............ 11 MOTU is reefed down in the Santa Barbara Channel. Hal DeVaney Photo: Clint Lewis © 04/21/2014 By Tom Davison Another Flicka down the dock also survived. s/y BLUE SKIES Not every Flicka is so lucky. Driving away from your Flicka and wondering if it will be Since the number of images that arrived there in a few days isn’t fun. P LEASE H ELP! would not have filled very many pages, I To keep this newsletter going, your help is decided to move up the publishing schedule of Joshua Wheeler’s article describes a great needed. Please consider sharing photos of RED RASCAL’s construction. The fifth weekend on Puget Sound aboard his Flicka s/y your Flicka, or sending a story about your article of twelve has been included in this SAMPAGUITA. latest trip, a recent upgrade, or your favorite issue. My plan is to publish one of the twelve anchorage or harbor. -

Watkins 27 Pg8 GOOD OLD BOAT Inspiring Hands-On Sailors

Composting Heads pg28 | Exploring Lasqueti Island pg36 | Review: Watkins 27 pg8 GOOD OLD BOAT Inspiring hands-on sailors 06 GoodOldBoat.com $8.00 US $8.00 CAN 06 Issue 132: May/June 2020 0 62825 97035 7 Odyssey HD Trinidad HD Hull Defense Hull Defense Multi-Season Ablative Multi-Season Hard Antifouling Bottom Paint Bottom Paint Solvent-based, 45.7% High 53.3% copper load, high copper content. excellent in all conditions. Smooth, durable finish. Hard, durable, long-lasting H Fast-Dry Technology. VOC finish. Fast-Dry Technology. HAMILTON compliant, compatible Compatible over hard finishes. over most finishes. 50 State VOC compliance. NEW HD bottom paint features the exclusive Pettit HD Hull Defense LIMITED 18 Month Warranty! MARINE Macerator Pump Manual Compact Toilet FREE CATALOG! 11.5 GPM. Brass and stainless steel internal 15.75" L x 13.4" H x 17.75" W. Features “lock- 376 full color pages, parts and pump body in thermo polymer with unlock” function for comfort and safety. Plug and a long lasting impeller. Inlet port 1.5" and play/interchangeable with other manual compact chock full of stuff outlet 1".12V. toilet models. boaters want. Request your copy today! $ 99 $ 99 117 ea 141 ea ALB-03-01-005 ALB-07-01-001 Order# 775155 Order# 775151 Totally submersible, RescueME EPIRB1 silent running and vibra- tionless. Ignition pro- Category II with GPS Bilge Pumps tected, water cooled, no Measuring 7" x 3.9" x 3.5", burnout when run dry. the world’s most compact NEW! HUGE EPIRB is easily stowed for SElection! emergencies. -

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC For Handicap Range Code 0-1 2-3 4 5-9 14 (Int.) 14 85.3 86.9 85.4 84.2 84.1 29er 29 84.5 (85.8) 84.7 83.9 (78.9) 405 (Int.) 405 89.9 (89.2) 420 (Int. or Club) 420 97.6 103.4 100.0 95.0 90.8 470 (Int.) 470 86.3 91.4 88.4 85.0 82.1 49er (Int.) 49 68.2 69.6 505 (Int.) 505 79.8 82.1 80.9 79.6 78.0 A Scow A-SC 61.3 [63.2] 62.0 [56.0] Akroyd AKR 99.3 (97.7) 99.4 [102.8] Albacore (15') ALBA 90.3 94.5 92.5 88.7 85.8 Alpha ALPH 110.4 (105.5) 110.3 110.3 Alpha One ALPHO 89.5 90.3 90.0 [90.5] Alpha Pro ALPRO (97.3) (98.3) American 14.6 AM-146 96.1 96.5 American 16 AM-16 103.6 (110.2) 105.0 American 18 AM-18 [102.0] Apollo C/B (15'9") APOL 92.4 96.6 94.4 (90.0) (89.1) Aqua Finn AQFN 106.3 106.4 Arrow 15 ARO15 (96.7) (96.4) B14 B14 (81.0) (83.9) Bandit (Canadian) BNDT 98.2 (100.2) Bandit 15 BND15 97.9 100.7 98.8 96.7 [96.7] Bandit 17 BND17 (97.0) [101.6] (99.5) Banshee BNSH 93.7 95.9 94.5 92.5 [90.6] Barnegat 17 BG-17 100.3 100.9 Barnegat Bay Sneakbox B16F 110.6 110.5 [107.4] Barracuda BAR (102.0) (100.0) Beetle Cat (12'4", Cat Rig) BEE-C 120.6 (121.7) 119.5 118.8 Blue Jay BJ 108.6 110.1 109.5 107.2 (106.7) Bombardier 4.8 BOM4.8 94.9 [97.1] 96.1 Bonito BNTO 122.3 (128.5) (122.5) Boss w/spi BOS 74.5 75.1 Buccaneer 18' spi (SWN18) BCN 86.9 89.2 87.0 86.3 85.4 Butterfly BUT 108.3 110.1 109.4 106.9 106.7 Buzz BUZ 80.5 81.4 Byte BYTE 97.4 97.7 97.4 96.3 [95.3] Byte CII BYTE2 (91.4) [91.7] [91.6] [90.4] [89.6] C Scow C-SC 79.1 81.4 80.1 78.1 77.6 Canoe (Int.) I-CAN 79.1 [81.6] 79.4 (79.0) Canoe 4 Mtr 4-CAN 121.0 121.6 -

Voyage of a Pocket Battleship

Summer 1998 Vol. 4, No. 1 Voyage of a Pocket Battleship By Anthony Steward After 260 days of exposure to the elements in a 19 foot open boat, you would think that I would have chosen the easy life. Every man has a right to choose his own oppressor, for me it would be the open ocean. Less than six months after circum-navigating, I was planning my next voyage. There weren’t many options as most records had already been set. I wanted to stay in a small boat as the challenge was greater. I was well aware that Kenichi Horie held the non-stop record in the smallest yacht, a 30 foot sloop. This was always on my mind and now with the advent of reliable watermakers, any size was possible. The only criteria that had to be met was that the yacht would have to be able to carry one ton of supplies and withstand Cape Horn weather. I Anthony Steward leaving Durban Harbor for a initially estimated that a 26 foot yacht circumnavigation aboard SELECTED RISKS. was the minimum length one could go. That was until I saw a Flicka sailing in Force Six on the South African Coast. the end of January 1994. One startling our size. After SELECTED RISKS’ On close inspection of this unique difference between the building of my first performance, the Knudsen Family little boat, I quickly came to realize a open boat and the fitting out of the were overwhelmed with enquiries for Flicka was equivalent to a 26 foot Flicka for a non-stop voyage was that Flickas; a big pity they had already yacht. -

Boat Buyers on the Prowl Pocket Cruisers? Down Market Draws out the Bargain Hunters

ON THE HORIZON toPSIDE PAint UPDAte 12-VOLT FriDGES PRACtiCAL WEBSiteS CAnoe-Stern CRUISerS toP-notCH HANDheLD VHFs Boat Buyers on the Prowl POCKET CRUISERS? Down market draws out the bargain hunters. o you have any reviews/rec- Dommendations/etc. for pocket very so often, I find myself cruisers that would be appropriate Eboat shopping and turn for a couple on Chesapeake Bay? to the reviews in “Practical Years ago, we sailed our FJ on inland Boat Buying.” I’m looking for iron keel, which should be lakes in Colorado and enjoyed it a trailerable, 20- to 26-foot, closely inspected before very much. We are now looking for- easy to rig, singlehandable buying one. The O’Day 23 is ward to retiring in a few years, and boat—and fast wouldn’t hurt a logical starter boat. Own- we would enjoy getting comfortable either. I am a beginner, think- ers seem generally pleased, with a fixed-keel boat. Lately, we ing about the Rhodes 22, giving it Fair to Good rat- have enjoyed daysailing around An- Tanzer 22, O’Day 23, or Bal- PS ADVISOR ings on the water. Watch for napolis, Md., in a Rainbow 24 and a boa 26. Did I mention I didn’t rudder delamination. The Rhodes 19. We are now looking for have a lot of money to spend? ubiquitous Catalina 22 also comes something with a cabin and head with its own cheering/advice section. that is safe for us to take on some Al Otman You might also add the S&S-designed overnighters, for example, from An- Lake Superior, Minn. -

Building a Flicka Building a Flicka

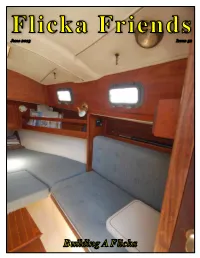

Flicka Friends June 2013 Issue 52 Building A Flicka Flicka Friends 1 FLICKA FRIENDS C ONTENTS The Flicka Is Back! Contents ......................................................... 2 The Flicka is Back! ......................................... 2 A Detour To Olympia .................................... 3 About Flicka Friends ..................................... 3 Flicka Projects Building a Flicka: Part 1 ................... 4 Bob Collier Galley Improvements ........................ 7 Jerry Ragland Draining The Cooler ........................... 14 Tom Davison Adding Air Conditioning .................. 16 Bob Collier Refitting s/y VALENTINE ................. 18 Dennis Pratt Flicka Trips Exploring Power Island .................... 10 Randy Richardson HE EXT SSUE Dave Simeon and Oceancraft Sailboats will be building the Flicka. T N I ? Photo: Oceancraft © 2013 The publication schedule is a bit behind the planned date. Still, here is the June 2013 issue of By Tom Davison from Pacific Seacraft. Dave’s new company Flicka Friends for your enjoyment. s/y BLUE SKIES will operate out of Wayfarer’s Cove Marina. The July issue of Flicka Friends will be another Just before heading off to work on April 22, They are providing support and some parts photo gallery issue. If you have an image from an e-mail was found in my computer in-box. for existing Flickas. This is great news for the the summer of 2013 and a caption about your It was from Gus Beare with a forwarded Flicka 20 sailing community. You can contact Flicka, please consider forwarding it me for message from Dave Simeon of Dawson Creek Oceancraft at: publication as soon as you can. If I can get Boat Works. twenty images or so, I’ll have another photo Oceancraft Yachts gallery issue to publish. -

Mainsail Insignia Guide - Page 1

Mainsail Insignia Guide - Page 1 210 420 470 505 Abbott 22 Able 20 Aero B Alajuela 33 Albacore Alberg 22 Alberg 30 Alberg Daystar Albin Albin Alpha Albin Ballard Alb Express Alb Vega Alden 100 Allegra Allied 3X Allmand 23 Aloha Alpha Cat Alpha Sailboard Amazon Pilot Mainsail Insignia Guide - Page 2 Ansa Aphrodite 101 Apollo Appledore Pod Aqua Cat Aquarius 21 Aquarius Pilot Arpege Artena 33 Atlantic City Atlantic Sloop Avance Baba 30 Bahama Sandpiper Balboa 20 Banshee Barbarian Barberis Show Bay Hen Bay Tiger Bayfield BB 10-Meter Beachcomber Beetle Cat Beneteau Mainsail Insignia Guide - Page 3 Benford 30 Beverly BIC Dufour Birchminster 27 Blackwatch Block Island 40 Blue Jay Bluejacket 23 BlueNose Blue Ocean 42 Bombay Bowman Bristol 19 Bristol Channel Buccaneer Cutter Buccaneer Bulls Eye Buttercup Butterfly C Scow Chrysler Cabo Rico Cal 20 Cal 36 Caliber Camelot Mainsail Insignia Guide - Page 4 Cape Cod Cape Dory 25 Cape Dory Capri 14 Catalina Cat Typhoon Capri 22 Carib Dory Cascade Catalina 25 Catfisher Cay Celebrity Celere Celestial Challenger 32 Cheetah Cat Cherubini 44 Chien Yu Christina 46 Chrysler 20 CL 11 Clark 31 Clipper MK21 CMS 41 Columbia Comanche Mainsail Insignia Guide - Page 5 Comet Comfort 34 Comfort 36 Com-Pac 27 Compis Concordia Contessa Contessa 26 Contest 36 Corbin 39 Yawl Cormorant Cornish Cornish Coronado Cove Crabber MKII Shrimper Crealock 34 Crealock 37 Creekmore 23 Cross Cruising World Trimarans Offshore Crystal Cat CS CSY CT Curtis Hawk Mainsail Insignia Guide - Page 6 Cyclone Cygnet 48 Cygnus Dana 24 D and M Dawson -

Self Steering for a Flicka Jobst Vandrey S/V Solar Wind

Winter 2001 Vol. 6, No. 4 The Flicka is “Out of Production” Flicka Friends - Winter 2001 Contents From The Editor s/v KITTIWAKE & The Gulf 1 Hal DeVaney By Tom Davison newsletter can put in the web page. Another advantage of Publisher is the Contents 2 In my spare time this summer, I ability to create postscript files that converted the Flicka Home Page from can be “distilled” into Acrobat PDF From The Editor 2 Adobe Pagemill to Microsoft files. Besides reducing the Publisher Tom Davison Publisher and the “new” Flicka Home files down from 15-20 MB to 100-300 Page is approaching 250 individual KB, Flicka Friends PDF files can be Flicka “Out of Production” 2 pages. While the Adobe software placed on internet for all to download. Pacific Seacraft would work well for the web, I Since they are in full color and are converted Rod Bruckdorfer’s web originals, anyone with a color printer All Aboard? 3 pages to Microsoft Publisher. While ends up with the best results. Tom Davison some may view this as going backwards, Publisher offers a number I’d like to thank Bruce P. Bingham About Flicka Friends 3 of features most web publishing again for allowing me to reprint the programs do not. FLICKA—A Happy Little Ship Distant Horizons 4 article. Since most new Flicka owners Rod Bruckdorfer Since I am the Editor for this may not have access to the 1980 issue newsletter and the WebCaptain for of Small Boat Journal, this should be a YAHOO Flicka20 Group 5 the Flicka Home Page, software was welcome addition to their Flicka files. -

North American Portsmouth Yardstick Table of Pre-Calculated Classes

North American Portsmouth Yardstick Table of Pre-Calculated Classes A service to sailors from PRECALCULATED D-PN HANDICAPS CENTERBOARD CLASSES Boat Class Code DPN DPN1 DPN2 DPN3 DPN4 4.45 Centerboard 4.45 (97.20) (97.30) 360 Centerboard 360 (102.00) 14 (Int.) Centerboard 14 85.30 86.90 85.40 84.20 84.10 29er Centerboard 29 84.50 (85.80) 84.70 83.90 (78.90) 405 (Int.) Centerboard 405 89.90 (89.20) 420 (Int. or Club) Centerboard 420 97.60 103.40 100.00 95.00 90.80 470 (Int.) Centerboard 470 86.30 91.40 88.40 85.00 82.10 49er (Int.) Centerboard 49 68.20 69.60 505 (Int.) Centerboard 505 79.80 82.10 80.90 79.60 78.00 747 Cat Rig (SA=75) Centerboard 747 (97.60) (102.50) (98.50) 747 Sloop (SA=116) Centerboard 747SL 96.90 (97.70) 97.10 A Scow Centerboard A-SC 61.30 [63.2] 62.00 [56.0] Akroyd Centerboard AKR 99.30 (97.70) 99.40 [102.8] Albacore (15') Centerboard ALBA 90.30 94.50 92.50 88.70 85.80 Alpha Centerboard ALPH 110.40 (105.50) 110.30 110.30 Alpha One Centerboard ALPHO 89.50 90.30 90.00 [90.5] Alpha Pro Centerboard ALPRO (97.30) (98.30) American 14.6 Centerboard AM-146 96.10 96.50 American 16 Centerboard AM-16 103.60 (110.20) 105.00 American 17 Centerboard AM-17 [105.5] American 18 Centerboard AM-18 [102.0] Apache Centerboard APC (113.80) (116.10) Apollo C/B (15'9") Centerboard APOL 92.40 96.60 94.40 (90.00) (89.10) Aqua Finn Centerboard AQFN 106.30 106.40 Arrow 15 Centerboard ARO15 (96.70) (96.40) B14 Centerboard B14 (81.00) (83.90) Balboa 13 Centerboard BLB13 [91.4] Bandit (Canadian) Centerboard BNDT 98.20 (100.20) Bandit 15 Centerboard -

Flicka Friends Vol 5 No 4

Flicka Friends Fall - 2000 Volume 5, Number3 One Way to Get A Flicka By Dave Kenyon My dad built a small plywood sailboat when I was a toddler and I grew up on ever larger sailboats since then. At about the age of 17, I decided to build one too. In late 1974, Rudder Boat Plan was selling a neat little Bruce Bingham 20 footer and my dad suggested that design. I paid $110.00 for a complete set of lofting sheets and drawings for a ferro- cement Flicka. When I started, I naively thought I could build this boat in a few years for a thousand dollars. Hey, I was only 17. I figured that I could build a nice boat for about half the price of buying one and it be that hard, right? Thirteen years later, I launched the QED and it cost about half of what it would cost to buy one, sort of. See, when Pacific Seacraft purchased the Flicka plans and started production, the boat cost about $15,000 (back in the late Attaching the lathe to the mold frames - the QED 70’s). By the time I finished, in 1987, begins to take shape, but there is still a long way to the Flicka was selling for about $30,000 go to complete the mold (let alone the boat). and guess what, I built mine for about out, transferred the lines onto 13 or 14 $15,000 in materials. add through-hulls, or easily repair it. I had heard horror stories about homebuilt mold ribs cut out of plywood.