Marjane Satrapi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discursive Construction of Referential Truth in Art Spiegelman's Maus And

The Comic Book as Complex Narrative: Discursive Construction of Referential Truth in Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis By Hannah Beckler For honors in The Department of Humanities Examination Committee: Annjeanette Wiese Thesis Advisor, Humanities Paul Gordon Honors Council Representative, Humanitities Paul Levitt Committee Member, English April 2014 University of Colorado at Boulder Beckler 2 Abstract This paper addresses the discursive construction of referential truth in Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. I argue that referential truth is obtained through the inclusion of both correlative truth and metafictional self-reflection within a nonfictional work. Rather than detracting from their obtainment of referential truth, the comic book discourses of both Maus and Persepolis actually increase the degree of both referential truth and subsequent perceived nonfictionality. This paper examines the cognitive processes employed by graphic memoirs to increase correlative truth as well as the discursive elements that facilitate greater metafictional self-awareness in the work itself. Through such an analysis, I assert that the comic discourses of Maus and Persepolis increase the referential truth of both works as well as their subsequent perceived nonfictionality. Beckler 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………….4 2. Part One: Character Recognition and Reader Identification in Images……..7 3. Part Two: Representing Space, Time, and Movement……………………..15 4. Part Three: Words and Images……………………………………………..29 5. Part Four: The Problem of Memory in Representation……………...……..34 6. Part Five: Subjective Reconstruction and Narration……………………….48 7. Conclusion………………………………………………………………….56 Works Cited………………………………………………………………...60 Beckler 4 Although comic books are often considered a lower medium of literary and artistic expression compared to works of literature, art, or film, modern graphic novels often challenge the assumption that such a medium is not capable of communicating complex and nuanced stories. -

The Language of Narrative Drawing: a Close Reading of Contemporary Graphic Novels

The Language of Narrative Drawing: a close reading of contemporary graphic novels Abstract: The study offers an alternative analytical framework for thinking about the contemporary graphic novel as a dynamic area of visual art practice. Graphic narratives are placed within the broad, open-ended territory of investigative drawing, rather than restricted to a special category of literature, as is more usually the case. The analysis considers how narrative ideas and energies are carried across specific examples of work graphically. Using analogies taken from recent academic debate around translation, aspects of Performance Studies, and, finally, common categories borrowed from linguistic grammar, the discussion identifies subtle varieties of creative processing within a range of drawn stories. The study is practice-based in that the questions that it investigates were first provoked by the activity of drawing. It sustains a dominant interest in practice throughout, pursuing aspects of graphic processing as its primary focus. Chapter 1 applies recent ideas from Translation Studies to graphic narrative, arguing for a more expansive understanding of how process brings about creative evolutions and refines directing ideas. Chapter 2 considers the body as an area of core content for narrative drawing. A consideration of elements of Performance Studies stimulates a reconfiguration of the role of the figure in graphic stories, and selected artists are revisited for the physical qualities of their narrative strategies. Chapter 3 develops the grammatical concept of tense to provide a central analogy for analysing graphic language. The chapter adapts the idea of the graphic „confection‟ to the territory of drawing to offer a fresh system of analysis and a potential new tool for teaching. -

FA 49V.01 Course Syllabus

An Elective Course for Undergraduate and Graduate Students of any discipline and for English Language Students GRAPHIC NARRATIVE IN CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE & ART: EVOLUTION OF COMIC BOOK TO GRAPHIC NOVEL ✓ Basic Requirements: Appropriate language skills required by the University. ➢ This course should be of interest to anyone concerned with verbal & visual communications, popular forms, mass culture, history and its representation, colonialism, politics, journalism, writing, philosophy, religion, mythology, mysticism, metaphysics, cultural exchanges, aesthetics, post-modernism, theatre, film, comic art, collections, popular art & culture, literature, fine arts, etc. ➢ This course may have a specific appeal to fans and/or to those who are curious about this vastly influential, widely popular, most complex and thought-provoking work of contemporary literature and art form, the ‘Comics’; however it does not presume a prior familiarity with graphic novels and/or comics, just an overall enthusiasm to learn new things from a new angle and an open mind. ✓ Prerequisites: ➢ FA489 & FA49V: ‘By consent’ selection of students. ➢ FA490: Upon successful completion of FA489. ✓ Co-requisites: ➢ FA489 & FA49V: Freshmen who graduated from a high school with an English curriculum or passed BU proficiency test with an A; & sophomore, junior, senior students. ➢ FA490: Successful completion of FA 489. ✓ Recommended Preparation: Reading all of the required readings and as many from the suggested reading list. Idea Description: Is ‘comics’ a form of both literature and art? Certainly the answer is “yes” but there are many people who reject the idea, yet many other people call those people old-school intellectuals. However, in recent years, many scholars, critics and faculty alike have accepted ‘comics’, often dubbed by many publishers as ‘graphic novel’, as a respected form of both literature and art. -

Kate Warren, “Persepolis: Animation, Representation and the Power of the Personal Story,” Screen Education, Winter 2010, Issue 58, PP

Kate Warren, “Persepolis: Animation, Representation and the Power of the Personal Story,” Screen Education, Winter 2010, Issue 58, PP. 117-23. Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis {2007), based on her graphic novels of the same name, is one of a growing number of films thiat employs formats such as animation, which is traditionally aimed at younger audiences, to depict complex and confronting subject matter. In doing so, such films offer interesting avenues of investigation for students and educators, not only in terms of the stories told, but also in relation to how these artistic and aesthetic techniques affect the narrative structures and modes of representation offered. Author, illustrator and filmmaker Marjane Satrapi was born in Rasht, Iran, in 1969.' As a child she witnessed one of the most dramatic periods in her country's recent history: the overthrow of the shah in 1979, the subsequent Islamic Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War. The film Persepolis charts her childhood in Tehran, her secondary education in Vienna and her tertiary studies in Iran, and concludes with her decision to leave Iran permanently for France. The formative years of childhood, adolescence and early adulthood are negotiated during a period of great flux and trauma for her country, her family and herself. Through her graphic novels and this film, Satrapi depicts these events and experiences with frankness, humour, poignancy and emotional power. Questions of representation When approaching cultural and historical traumas - such as war, revolution and genocide - questions are often raised about how these events are to be represented, who is 'entitled' to represent them, and whether they should be represented at all. -

Graphic Narratives Catalog

Graphic Narratives Catalog *The blue blocks are works by women, the pink ones have multiple authors, and the yellow blocks are notes on categorization Curated by Kay Sohini and Comic Enthusiasts Worldwide Memoirs/Autobiographics Graphic Medicine Queerness Diaspora Narratives Conflicts/Wars/Disaster Drawn Graphic Cli-fi Mythology/Folklore Comics Journalism Miscellaneous Comic Scholarship The Dykes to Watch Out For, The Best We Could Do, Munnu: A Boy From Kashmir by Climate Changed by Burma Chronicles, Guy A City Inside, Tilie 1 Maus, Art Spiegelman Epileptic, David B. Everything Hillary Chute Alison Bechdel Thi Bui Malik Sajad Phillipe Squarzoni Adi Parva, Amruta Patil Delisle Walden Note: Partly Diaspora Narrative Comic Book History of Blue is the Warmest Color, Julie Shortcomings, Adrianne In the Shadow of No Towers. Art All Quite in Vikaspuri by Comics by Fred Van 2 Are You My Mother, Alison Bechdel Stitches, David Small. Sauptik, Amruta Patil Palestine, Joe Sacco Syllabus, Lynda Barry Maroh Tomine Spiegelman Sarnath Banerjee Lente and Ryan Dunlavey Note: Water conflict Note: Academics AD: New Orleans after Poppies of Iraq, Bridgette Findakly and Lewis American Born Chinese, Vietnamerica: A Family's Journey Habibi by Craig Safe Area Gorazde, Joe Blankets, Craig 3 Hyberbole and a Half, Allie Brosh Skim, Mariko and Jillian Tamaki the Deluge, Josh Trondheim Gene Luen Yang by GB Tran Thompson Sacco Thompson Neufeld Note: Coming of age, Note: Partly Diaspora Narrative Note: Also a Memoir romantic love Bhimayana: Experiences Marbles: Mania, Depression, Ms. Marvel Vol. 01 of Untouchability by Jerusalem by Guy 4 Fun Home, Alison Bechdel Michelangelo and Me by Ellen Kari, Amruta Patil (2014), G. -

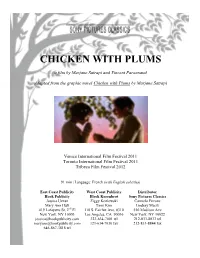

Chicken with Plums

CHICKEN WITH PLUMS a film by Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud Adapted from the graphic novel Chicken with Plums by Marjane Satrapi Venice International Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 Tribeca Film Festival 2012 91 min | Language: French (with English subtitles) East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Tami Kim Lindsay Macik 419 Lafayette St, 2nd Fl 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10003 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel [email protected] 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 646-867-3818 tel SYNOPSIS Teheran, 1958. Since his beloved violin was broken, Nasser Ali Khan, one of the most renowned musicians of his day, has lost all taste for life. Finding no instrument worthy of replacing it, he decides to confine himself to bed to await death. As he hopes for its arrival, he plunges into deep reveries, with dreams as melancholic as they are joyous, taking him back to his youth and even to a conversation with Azraël, the Angel of Death, who reveals the future of his children... As pieces of the puzzle gradually fit together, the poignant secret of his life comes to light: a wonderful story of love which inspired his genius and his music... DIRECTORS’ STATEMENT By Marjane Satrapi & Vincent Paronnaud Chicken with Plums is the story of a famous musician whose prized instrument has been ruined. -

Of Maus and Gen: Author Avatars in Nonfiction Comics

267 Of Maus and Gen: Author Avatars in Nonfiction Comics Moritz Fink In many ways, Art Spiegelman's Mausand Keiji Nakazawa's Barefoot Gen appear to be literary siblings. While of different national as weil as cultural origins, both works have their roots in the 1970s; both redefined the notion of comics by demonstrating the medium's compatibility with such serious subjects as world history and historical trauma; and both provided autobiographical accounts by featuring their authors on the page. And yet, the two canonic texts could not be more different in their stylistic approaches. Not only with regard to the cultural traditionsout ofwhich Maus (American comics) and Gen (Japanese manga) grew, but also in terms of how the artists depict themselves and what functions their avatars have within the respective work. Spiegelman brings hirnselfexplicitly to the fore in a highly self-reftexive fashion, following the autobiographical tradition ofU.S. independent comics. Nakazawa, by contrast, rather withdraws hirnself by replacing his original stand-in from the earlier work I Saw It, "Keiji," with the heroic kid Gen. This essay investigates instances where authors of nonfiction comics insert themselves into their works via avatar characters -- a narrative device that corresponds to the traditionally foregrounded roJe of the creator-artist in the comics medium. In tracing the evolution of author representations in nonfiction comics, I will create links to Bill Nichols's classification ofvarious modes ofdocumentary film. While there have been efforts to transfer Nichols 's concept to comics (Adams, 2008; Lefevre, 2013), none ofthem has focused specifically on the aspect of the author avatar in this context. -

Graphic Narrative: Comics in Contemporary Art

An Elective Course for Undergraduate and Graduate Students of any discipline and for English Language Students GRAPHIC NARRATIVE IN CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE & ART: EVOLUTION OF COMIC BOOK TO GRAPHIC NOVEL Basic Requirements: Appropriate language skills required by the University. This course should be of interest to anyone concerned with verbal & visual communications, popular forms, mass culture, history and its representation, colonialism, politics, journalism, writing, philosophy, religion, mythology, mysticism, metaphysics, cultural exchanges, aesthetics, post-modernism, theatre, film, comic art, collections, popular art & culture, literature, fine arts, etc. This course may have a specific appeal to fans and/or to those who are curious about this vastly influential, widely popular, most complex and thought-provoking work of contemporary literature and art form, the ‘Comics’; however it does not presume a prior familiarity with graphic novels and/or comics, just an overall enthusiasm to learn new things from a new angle and an open mind. Prerequisites: FA489: ‘By consent’ selection of students. FA490: Upon successful completion of FA489. Co-requisites: FA489: Freshmen who graduated from a high school with an English curriculum or passed BU proficiency test with an A; & sophomore, junior, senior students. FA490: Successful completion of FA 489. No requisites: FA 49I, FA49J, FA49V. Recommended Preparation: Reading all of the required readings and as many from the suggested reading list. Idea Description: Is ‘comics’ a form of both literature and art? Certainly the answer is “yes” but there are many people who reject the idea, yet many other people call those people old-school intellectuals. However, in recent years, many scholars, critics and faculty alike have accepted ‘comics’, often dubbed by many publishers as ‘graphic novel’, as a respected form of both literature and art. -

Orientalism, Gender, and Nation Defied by an Iranian Woman: Feminist Orientalism and National Identity in Satrapi’S Persepolis and Persepolis 2

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 1 Article 8 February 2020 Orientalism, Gender, and Nation Defied yb an Iranian Woman: Feminist Orientalism and National Identity in Satrapi’s Persepolis and Persepolis 2 Diego Maggi Georgetown University Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Maggi, Diego (2020). Orientalism, Gender, and Nation Defied yb an Iranian Woman: Feminist Orientalism and National Identity in Satrapi’s Persepolis and Persepolis 2. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(1), 89-105. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss1/8 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Orientalism, Gender, and Nation Defied by an Iranian Woman: Feminist Orientalism and National Identity in Satrapi’s Persepolis and Persepolis 2 By Diego Maggi1 Abstract Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novels Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood (2003) and Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return (2004) —focused on her youth and early adulthood in Iran and Austria— reveal in many ways the conflicting coexistence between the West —Europe and North America— and the Middle East. This article explores feminist Orientalism and national identity in both Satrapi’s works, with the purpose of demonstrating the manners that these comics complicate and challenge binary divisions commonly related to the tensions amid the Occident and the Orient, such as East-West, Self-Other, civilized-barbarian and feminism-antifeminism. -

Access Provided by City University of New York at 10/18/11 8:39PM GMT What to Expect When You Pick up a Graphic Novel

Access Provided by City University of New York at 10/18/11 8:39PM GMT What to Expect When You Pick Up a Graphic Novel Lisa Zunshine We live in other people’s heads: avidly, reluctantly, consciously, unawares, gropingly, inescapably. A stranger sitting across the table at the library turns away from her laptop screen, extends her forearm, and begins to move her eyes from the tip of her index finger to her nose and back. It’s a kind of eye calisthenics; she obviously wants to keep her near- sightedness under control. I sigh and look away: I really should do the same exercises, but I am too lazy. When I look at her again, I see that she sees me looking at her, so I let my glance slide past her casually: I don’t want her to think that I am staring. Our daily lives are unimaginable without such constant nonverbal interactions. We explain other people’s observable behavior in terms of unobservable mental states and assume that they explain our behavior the same way. Mental states: thoughts, desires, feelings, intentions. She does that exercise because she wants to improve her eyesight. I sigh because I feel bad about my laziness. I don’t know what she thinks when she notices my look, but I think up a little narrative about what she might think and what I should do so that she doesn’t think this. Note that to describe this for you now I construct a neat sequence of sentences, making it seem like an evenly paced, conscious, and fully verbalized process, but when it was actually happening it was fast, messy, intuitive, not particularly conscious, and certainly not verbalized. -

Table of Contents

MASTER LIST OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Master List of Contents .............................................vii Clumsy..................................................................... 162 Publisher’s Note .........................................................xi Color Trilogy, The ................................................... 166 Introduction ............................................................... xv Complete Essex County, The ................................... 170 Contributors ............................................................xvii Complete Fritz the Cat, The .................................... 174 Contract with God, And Other A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge........................... 1 Tenement Stories, A ...........................................179 Adventures of Luther Arkwright, The .......................... 5 Curious Case of Benjamin Button, The................... 183 Adventures of Tintin, The ............................................ 9 David Boring ........................................................... 187 Age of Bronze: The Story of the Trojan War ............. 15 Dead Memory .......................................................... 190 Age of Reptiles .......................................................... 20 Dear Julia ............................................................... 194 Airtight Garage of Jerry Cornelius .......................... 24 Deogratias: A Tale of Rwanda ................................ 198 Alan’s War: The Memories of G.I. Alan Cope........... 28 Diary of a Mosquito -

Persepolis Film Study Guide Director: Vincent Paronnaud, Marjane Satrapi 2007 | Animation | 96 Minutes | France, USA | French, English, Persian, German | Rated PG-13

Persepolis Film Study Guide Director: Vincent Paronnaud, Marjane Satrapi 2007 | Animation | 96 Minutes | France, USA | French, English, Persian, German | Rated PG-13 Synopsis: In 1970s Iran, Marjane 'Marji' Statrapi watches events through her young eyes and her idealistic family of a long dream being fulfilled by the hated Shah's defeat in the Iranian Revolution of 1979. However as Marji grows up, she witnessed first hand how the new Iran, now ruled by Islamic fundamentalists, has become a repressive tyranny on its own. With Marji dangerously refusing to remain silent at this injustice, her parents send her abroad to Vienna to study for a better life. However, this change proves an equally difficult trial with the young woman finding herself in a different culture loaded with abrasive characters and profound disappointments that deeply trouble her. Even when she returns home, Marji finds that both she and her homeland have changed too much and the young woman and her loving family must decide where she truly belongs. Post-Screening Discussion Questions 1. What do you know about the Iranian Revolution? How is the Iranian Revolution similar to the recent events in Egypt, Libya and London? How is it different? 2. What is the role of women in the story? Compare and contrast the various women: Marji, her mother, her grandmother, her school teachers, the maid, the neighbors, the guardians of the revolution. How do they respond and react, rebel against and conform to their environment? 3. Discuss the role and importance of religion in Persepolis. How does religion define certain characters in the book, and affect the way they interact with each other? Is the author making a social commentary on religion, and in particular on Fundamentalism? What do you think the film is saying about religion’s effect on the individual and society? 4.