Abraham Atkins and General Communion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of Election Vale Parishes

NOTICE OF ELECTION Vale of White Horse District Council Election of Parish Councillors for the parishes listed below Number of Parish Number of Parish Parishes Councillors to be Parishes Councillors to be elected elected Abingdon-on-Thames: Abbey Ward 2 Hinton Waldrist 7 Abingdon-on-Thames: Caldecott Ward 4 Kennington 14 Abingdon-on-Thames: Dunmore Ward 4 Kingston Bagpuize with Southmoor 9 Abingdon-on-Thames: Fitzharris Ock Ward 2 Kingston Lisle 5 Abingdon-on-Thames: Fitzharris Wildmoor Ward 1 Letcombe Regis 7 Abingdon-on-Thames: Northcourt Ward 2 Little Coxwell 5 Abingdon-on-Thames: Peachcroft Ward 4 Lockinge 3 Appleford-on-Thames 5 Longcot 5 Appleton with Eaton 7 Longworth 7 Ardington 3 Marcham 10 Ashbury 6 Milton: Heights Ward 4 Blewbury 9 Milton: Village Ward 3 Bourton 5 North Hinksey 14 Buckland 6 Radley 11 Buscot 5 Shrivenham 11 Charney Bassett 5 South Hinksey: Hinksey Hill Ward 3 Childrey 5 South Hinksey: Village Ward 3 Chilton 8 Sparsholt 5 Coleshill 5 St Helen Without: Dry Sandford Ward 5 Cumnor: Cumnor Hill Ward 4 St Helen Without: Shippon Ward 5 Cumnor: Cumnor Village Ward 3 Stanford-in-the-Vale 10 Cumnor: Dean Court Ward 6 Steventon 9 Cumnor: Farmoor Ward 2 Sunningwell 7 Drayton 11 Sutton Courtenay 11 East Challow 7 Uffington 6 East Hanney 8 Upton 6 East Hendred 9 Wantage: Segsbury Ward 6 Fyfield and Tubney 6 Wantage: Wantage Charlton Ward 10 Great Coxwell 5 Watchfield 8 Great Faringdon 14 West Challow 5 Grove: Grove Brook Ward 5 West Hanney 5 Grove: Grove North Ward 11 West Hendred 5 Harwell: Harwell Oxford Campus Ward 2 Wootton 12 Harwell: Harwell Ward 9 1. -

Uffington and Baulking Neighbourhood Plan Website.10

Uffington and Baulking Neighbourhood Plan 2011-2031 Uffington Parish Council & Baulking Parish Meeting Made Version July 2019 Acknowledgements Uffington Parish Council and Baulking Parish Meeting would like to thank all those who contributed to the creation of this Plan, especially those residents whose bouquets and brickbats have helped the Steering Group formulate the Plan and its policies. In particular the following have made significant contributions: Gillian Butler, Wendy Davies, Hilary Deakin, Ali Haxworth, John-Paul Roche, Neil Wells Funding Groundwork Vale of the White Horse District Council White Horse Show Trust Consultancy Support Bluestone Planning (general SME, Characterisation Study and Health Check) Chameleon (HNA) Lepus (LCS) External Agencies Oxfordshire County Council Vale of the White Horse District Council Natural England Historic England Sport England Uffington Primary School - Chair of Governors P Butt Planning representing Developer - Redcliffe Homes Ltd (Fawler Rd development) P Butt Planning representing Uffington Trading Estate Grassroots Planning representing Developer (Fernham Rd development) R Stewart representing some Uffington land owners Steering Group Members Catherine Aldridge, Ray Avenell, Anna Bendall, Rob Hart (Chairman), Simon Jenkins (Chairman Uffington Parish Council), Fenella Oberman, Mike Oldnall, David Owen-Smith (Chairman Baulking Parish Meeting), Anthony Parsons, Maxine Parsons, Clare Roberts, Tori Russ, Mike Thomas Copyright © Text Uffington Parish Council. Photos © Various Parish residents and Tom Brown’s School Museum. Other images as shown on individual image. Executive Summary This Neighbourhood Plan (the ‘Plan’) was prepared jointly for the Uffington Parish Council and Baulking Parish Meeting. Its key purpose is to define land-use policies for use by the Planning Authority during determination of planning applications and appeals within the designated area. -

Oxfordshire. Oxpo:Bd

DI:REOTO:BY I] OXFORDSHIRE. OXPO:BD. 199 Chilson-Hall, 1 Blue .Anchor,' sat Fawler-Millin, 1 White Hart,' sat Chilton, Berks-Webb, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat Fawley, North & South-Gaskin, 'Anchor,' New road, Chilton, Bucks-Shrimpton, ' Chequers,' wed. & sat. ; wed. & sat Wheeler 'Crown,' wed & sat Fencott--Cooper, ' White Hart,' wed. & sat Chilworth-Croxford, ' Crown,' wed. & sat.; Honor, Fewcot-t Boddington, ' Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat 'Crown,' wed. & sat.; Shrimpton, 'Chequers,'wed.&sat Fingest--Croxford, ' Crown,' wed. & sat Chimney-Bryant, New inn, wed. & sat Finstock-:Millin, 'White Hart,' sat Chinnor-Croxford, 'Crown,' wed, & sat Forest Hill-White, 'White Hart,' mon. wed. fri. & sat. ; Chipping Hurst-Howard, ' Crown,' mon. wed. & sat Guns tone, New inn, wed. & sat Chipping Norton-Mrs. Eeles, 'Crown,' wed Frilford-Baseley, New inn, sat. ; Higgins, 'Crown,' Chipping Warden-Weston, 'Plough,' sat wed. & sat.; Gaskin, 'Anchor,' New road, wed. & sat Chiselhampton-Harding, 'Anchor,' New road, sat.; Fringford-Bourton, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat Jones, 'Crown,' wed. & sat.; Moody, 'Clarendon,' sat Fritwell-Boddington, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat Cholsey-Giles, ' Crown,' wed. & sat Fyfield-Broughton, 'Roebuck,' fri.; Stone, 'Anchor,' Cirencester-Boucher, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat New road, sat.; Fisher, 'Anchor,' New road, fri Clanfield-Boucher, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat Garford-Gaskin, 'Anchor,' New road, wed Claydon, East, Middle & Steeple-Bicester carriers Garsington-Howard, ' Crown,' mon. wed. & sat. ; Dover, Cleveley-Eeles, 'Crown,' sat New inn, mon. wed. fri. & sat.; Townsend, New inn, Clifton-by-Deddington-Boddington, 'Anchor,' wed. & mon. wed. •& sat sat.; Weston, 'Plough,' sat Glympton-Jones, 'Plough,' wed.; Humphries, 'Plough,' Clifton Hampden-Franklin, 'Chequers,' & 'Anchor,' sat New road, sat Golden Ball-Nuneham & Dorchester carriers Coate Bryant, New inn, wed. -

Wantage Deanery Synod Reps 2020

Dorchester Archdeaconry Wantage Deanery Notification of Deanery Synod Representatives for new triennium 2020-2023 (Note important change: CRR Part 3 Rule 15 (5) new triennium starts on 1st July 2020) Reported Electoral Allocated No. Formula agreed by Diocesan Roll as at reps as at Synod November 2019 Parish 20/12/2019 20/12/2019 Elected Electoral roll size lay reps Ardington with Lockinge 36 1 up to 40 1 Childrey with West Challow 51 2 41–80 2 Denchworth 17 1 81–160 3 East Challow 37 1 161–240 4 East Hendred 44 2 241–320 5 321–400 6 Grove 136 3 Hanney 21 1 401–500 7 Letcombe Bassett 24 1 501–600 8 Letcombe Regis 47 2 601–720 9 721–840 10 Sparsholt with Kingston Lisle 34 1 Wantage 164 4 841–1000 11 West Hendred 28 1 >1000 12 TOTAL 639 20 Key: Estimated where no returns made at 20/12/2019 Please note: The No. of Deanery Synod reps has been calculated based on the ER figures submitted up to 20/12/2019 as presented at each APCM held in 2019. This information has either been taken from the online submission (primary source); the ER certificate; or information received by email and telephone conversations. 2019 was an Electoral Roll Revision year so it has therefore had an impact on the number of places some deaneries / parishes have been allocated. If you would like to query these figures you MUST provide evidence of your APCM figure in 2019 as accepted at your APCM. Regrettably not all parishes returned this information and therefore any parishes whereby the figures are shown in yellow, places have been calculated on an estimated basis and therefore may not reflect an accurate picture. -

White Horse Hill Circular Walk

WHITE HORSE HILL CIRCULAR WALK 4¼ miles (6¾ km) – allow 2 hours (see map on final page) Introduction This circular walk within the North Wessex Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in Oxfordshire is 7 miles (11km) west of Wantage. It takes you through open, rolling downland, small pasture fields with some wonderful mixed hedgerows, woodland and a quintessential English village. It includes a classic section of The Ridgeway, with magnificent views of the Vale of White Horse to the north, and passes the unique site of White Horse Hill before descending the steep scarp slope to the small picturesque village of Woolstone in the Vale. The walk is waymarked with this ‘Ridgeway Circular Route’ waymark. Terrain and conditions • Tracks, field paths mostly through pasture and minor roads. • Quite strenuous with a steep downhill and uphill section. 174m (571 feet) ascent and descent. • There are 9 gates and one set of 5 steps, but no stiles. • Some paths can be muddy and slippery after rain. • There may be seasonal vegetation on the route. Preparation • Wear appropriate clothing and strong, comfortable footwear. • Carry water. • Take a mobile phone if you have one but bear in mind that coverage can be patchy in rural areas. • If you are walking alone it’s sensible, as a simple precaution, to let someone know where you are and when you expect to return. Getting there By Car: The walk starts in the National Trust car park for White Horse Hill (parking fee), south off the B4507 between Swindon and Wantage at map grid reference SU293866. -

2 DROVE WAY, Kingston Lisle, Nr Wantage, Oxfordshire OX12 9QW

2 DROVE WAY, Kingston Lisle, Nr Wantage, Oxfordshire OX12 9QW FAR REACHING VIEWS, TRANQUIL SETTING & STEEPED IN POTENTIAL KINGSTON LISLE Oxford c19miles Didcot Stn c15miles Wantage c5.3miles This unusual semi-detached house enjoys something very close to pole position, sitting on the crown of the hill off a leafy lane with far reaching views over farmland and the Vale of White Horse. The property sits in a generous plot of circa 0.2 of an acre in a wonderfully peaceful setting so it looks, subject to the relevant planning consents, as if this is an exceptional opportunity to extend, remodel and create a really interesting home in a near perfect tranquil setting. The current accommodation includes, hall, sitting room, snug, kitchen with Rayburn, 3 bedrooms, bathroom and separate WC. Central heating is oil fired from the Rayburn and the walls have the benefit of cavity wall insulation. Outside there is a large rear garden adjacent to farmland and a single garage to the side as well as a front garden and driveway parking. Total circa 1,291Sq Ft Gross Internal Guide Price: £375,000 Cuan Ryan Vale & Downlands (t) 01235 772299 (m) 07545 261810 (e) [email protected] 2 DROVE WAY Drove Way, Kingston Lisle Approximate Gross Internal Area 1291 Sq Ft/120 Sq M Porch Kitchen Bedroom 2 3.63 x 3.05 3.63 x 3.02 Living Room 11'11" x 10'0" 11'11" x 9'11" Master Bedroom 4.55 x 3.66 4.55 x 3.66 14'11" x 12'0" 14'11" x 12'0" Hall 7.72 x 2.11 25'4" x 6'11" Ground Floor First Floor Snug Bedroom 3 N 3.66 x 3.05 3.66 x 3.02 12'0" x 10'0" 12'0" x 9'11" E W S FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY - NOT TO SCALE The position & size of doors, windows, appliances and other features are approximate only. -

Uffington in Fiction and Fact

THE OXFORDSHIRE LOCAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION (OLHA) UFFINGTON IN FICTION AND FACT A study day to be held on SUNDAY 10 th May 2015 at the Thomas Hughes Memorial Hall, Broad Street, Uffington, SN7 7RA (map overleaf) Uffington, a small downland village, was home to Thomas Hughes, MP and social reformer, lawyer, judge and author, best known for writing ‘Tom Brown’s Schooldays’. In 1859 he published ‘The Scouring of the White Horse; or the Long Vacation Ramble of a London Clerk’ which is a fictionalised account of a real event. A hodge-podge of legend, customs and local ballads, the White Horse is said to celebrate the victory of Alfred over the Danes in 871 AD. 9.30 Coffee and Registration 10.00 OLHA Annual General Meeting 10.45 A Step Through Uffington’s Past Sharon Smith, curator of the Tom Brown’s School Museum for the last twenty years, has co-authored several local history publications, produced annual special exhibitions, and organised a community dig on the Uffington Iron Age site. 11.45 Living with the White Horse: Excavations of White Horse Hill and the nearby hillforts of Segsbury Camp and Alfred’s Castle Gary Lock, Emeritus Professor at the Oxford School of Archaeology, has directed extensive excavations of the Ridgeway hillforts and of the Marcham/Frilford site in the Vale of the White Horse. 1.00 Lunch The Fox and Hounds, a freehouse, serves the usual pub dishes as well as Sunday roasts. It is the only pub in the village and it would be best to book – 01367 820680. -

Kingston Lisle Business Centre Kingston Lisle, Wantage

Kingston Lisle Business Centre B1 Business offices Kingston Lisle, Wantage, Oxfordshire OX12 9QX to let or for sale SALE A rare opportunity to let or buy office premises at Kingston Lisle Business Centre, nr. Wantage A choice of sizes and styles of rurally located B1 office premises, comprising of four complete buildings to rent or buy* with extensive allocated parking, situated approximately 6 miles west of Wantage in southern Oxfordshire and presently forming part of The Lonsdale Estate. (*”Units 1 to 4” can only be bought as a whole but are available as up to four separate lets) . Manor Farm Barn A Grade 2 Listed Building originating from the 1500’s with a real rustic feel about it featuring deep, red clay tiled roof pitches and extensive exposed beams/timber framing internally plus an impressive glazed entrance. The accommodation is accessible from three points if required and mainly ground floor, split between two divided but adjoining open plan areas, each with elevated work spaces over. The layout internally is based on conventional rectangular shapes and comprises (all dimensions to the internal face of the usable area, all floor areas approximate): Immediate reception area – 4.68m x 2.96m, built-in storage off Main open plan area – 9.59m x 8.30m overall, doors off to WC and large store room (21.80sq.m), stairs off to… First floor work space – 7.07m x 3.51m Secondary open plan area – 7.95m x 7.79m narrowing to 6.18m, door off to WC and stairs up to… Separate first floor work spaces – 4.87m x 4.34m and 4.87m x 3.63mm Area – 208.64sq.m (2,245sq.ft) plus storage and staff welfare. -

Notice of Election

NOTICE OF ELECTION Vale of White Horse District Council Election of councillors for the parishes listed below Number of councillors to Number of councillors to Parish Parish be elected be elected Abingdon-on-Thames: Abbey Ward 2 Harwell: Harwell Ward 9 Abingdon-on-Thames: Caldecott 4 Harwell: Harwell Oxford 2 Ward Campus Ward Abingdon-on-Thames: Dunmore 4 Hinton Waldrist 7 Ward Abingdon-on-Thames: Fitzharris Ock 2 Kennington 14 Ward Abingdon-on-Thames: Fitzharris 1 Kingston Bagpuize with 9 Wildmoor Ward Southmoor Abingdon-on-Thames: Northcourt 2 Kingston Lisle 5 Ward Abingdon-on-Thames: Peachcroft 4 Letcombe Regis 7 Ward Appleford-on-Thames 5 Little Coxwell 5 Appleton with Eaton 7 Longcot 5 Ardington and Lockinge 6 Longworth: East Ward 3 Ashbury 6 Longworth: West Ward 4 Blewbury 9 Marcham 10 Bourton 5 Milton: Heights Ward 4 Buckland 6 Milton: Village Ward 3 Buscot 5 North Hinksey 14 Charney Bassett 5 Radley 11 Childrey 5 Shrivenham 11 Chilton 8 South Hinksey 5 Coleshill 5 Sparsholt 5 Cumnor: Cumnor Hill Ward 4 St Helen Without: Dry 5 Sandford Ward Cumnor: Cumnor Village Ward 3 St Helen Without: Shippon 5 Ward Cumnor: Dean Court Ward 6 Stanford-in-the-Vale 10 Cumnor: Farmoor Ward 2 Steventon 9 Drayton 11 Sunningwell 7 East Challow 7 Sutton Courtenay 11 East Hanney 6 Uffington 6 East Hendred 9 Upton 6 Fyfield and Tubney 6 Wantage: Segsbury Ward 6 Great Coxwell 5 Wantage: Wantage Charlton 10 Ward Great Faringdon 14 Watchfield 8 Grove: Crab Hill Ward 1 West Challow 5 Grove: Grove Brook Ward 4 West Hanney 5 Grove: Grove North Ward 11 West Hendred 5 Wootton 12 1. -

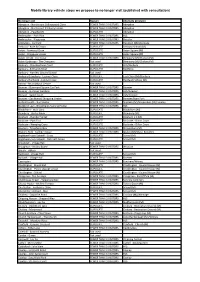

Mobile Library Vehicle Stops We Propose to No Longer Visit (Published with Consultation)

Mobile library vehicle stops we propose to no longer visit (published with consultation) No longer visit Reason Alternate provision Abingdon - Northcourt Collingwood Close FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Abingdon Abingdon - Northcourt Fitzharry's Arms FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Abingdon Abingdon - Peachcroft DUPLICATE Abingdon Ambrosden - Park Rise FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS HLS Ambrosden - Playgroup FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Bicester Ardington - Car Park FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Hendred (M)/Wantage Ashbury - Rose & Crown DUPLICATE Ashbury School (M) Aston - Foxwood Close DUPLICATE Aston Square (M) Aston - Kingsgate House DUPLICATE Aston Square (M) Aston Tirrold - The Close FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Blewbury (M)/Cholsey (M) Aston Upthorpe - The Chequers Not used Blewbury (M)/Cholsey (M) Banbury - Chamberlaine Court DUPLICATE HLS/Banbury Banbury - Edmunds Road DUPLICATE Neithrop Banbury - Harriers Ground School Not used Banbury Grimsbury - Levinot Close DUPLICATE East Close (M)/Banbury Banbury Hardwick - Juniper Close DUPLICATE Hardwick School (M) Barton - Roundabout Centre Not used Bicester - Bowmont Square Car Park FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Bicester Bicester - Hanover Gardens FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS HLS/Bicester Bicester - Saxon Court FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS HLS/Bicester Bicester - Southwold Shopping Centre FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Bicester/Bure Park Binfield Heath - Bus Shelter FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Shiplake (M)/Harpesden (M)/ Henley Blackbird Leys - Brookfields Nursing Home FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS HLS Blackthorn - Weir Lane DUPLICATE Blackthorn (M) Blewbury - Barley Mow DUPLICATE -

List for OX12 and Surrounding Villages

Defib List for OX12 and surrounding villages App Name The name that will Building Postcode Street Name(s) Town/Village Details and EXACT location Opening Hours be shown on the No. ‘Save a Life’ App Defib is inside the Bear Hotel. The Bear Hotel OX12 8AB No.14 Market Place Wantage Please ask at Reception for the Hotel opening hours defib. Defib is located outside the police Defib is Available 24/7 Public Wantage Library OX12 7BB Stirlings Road Wantage office / library Access Denchworth Defib is Available 24/7 Public Fitzwaryn School OX12 9ET Wantage On the right side of reception Road Access Tugwell Field, Defib is on the west side of the Defib is Available 24/7 Public Wantage Silver Band OX12 8FR Wantage Reading Road building, visible from the gate. Access Defib is wall mounted outside The Beacon on the corner of building The Beacon Council to the left of the reception Defib is Available 24/7 Public OX12 9BX Portway Wantage Building entrance, around the corner, to Access the right of the coffee shop entrance. Toilet Block at Defib is mounted on the outside Defib is Available 24/7 Public Wantage Memorial OX12 8DZ Manor Road Wantage wall of toilet block next to the Access Park children’s play area. Defib is wall mounted outside the Stockham Primary school. Next to the school garage Defib is Available 24/7 Public OX12 9HL Stockham Way Wantage School on the road side of the school Access gates. Wantage EXTERNAL. Defib is wall mounted Charlton Village Defib is Available 24/7 Public Community Support OX12 7HG Wantage on the front right hand side of the Road Access Service Main Entrance. -

Vale Living List 2019

LOCAL WILDIFE SITES IN VALE OF WHITE HORSE - 2019 This list includes Local Widlife Sites. Please contact TVERC for information on: • site location and boundary • area (ha) • designation date • last survey date • site description • notable and protected habitats and species recorded on site Site Code Site Name District Parish 40Y03 Osney Mead Oxford City Jericho and Osney 49J05 Appleton Upper Common Vale of White Horse Appleton-with-Eaton 48B01 Ashen Pen with Upper Black Bushes Vale of White Horse Wantage and Black Bushes Wood 29T03 Badbury Forest - Eaton Wood Vale of White Horse Great Faringdon 58G03 Blewbury Hill Vale of White Horse Blewbury 30A02 Buckland Marsh Vale of White Horse Buckland 39M06 Buckland Warren Woods Vale of White Horse Buckland 29N01/2 Buscot Park Lake Vale of White Horse Buscot 38X07 Castlehill Vale of White Horse Letcombe Regis 58H07 Chalk Pit and Lane Blewbury Vale of White Horse 39B02 Chaslins Copse Vale of White Horse Shellingford 40S03 Chawley footpath Vale of White Horse Cumnor 39T02 Cherbury Camp Vale of White Horse Charney Bassett 38R06 Cockrow Bottom Vale of White Horse Letcombe Bassett 29S02 Coxwell Wood Vale of White Horse Great Coxwell 50B08 Egrove Park Meadow Vale of White Horse Kennington 40N01 Farmoor Reservoir Vale of White Horse Cumnor 49U02 Gozzards Ford Fen Vale of White Horse Marcham 40X01 Harcourt Hill Scrub Vale of White Horse North Hinksey and South Hinksey 49P08 Hitchcopse South Sandpit Vale of White Horse Cothill 40K02 Holt Copse Vale of White Horse Fyfield and Tubney 48L01 Ilsley Bottom Vale