(Nhris) and Regional Human Rights Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

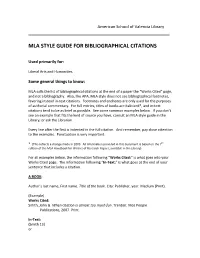

Mla Style Guide for Bibliographical Citations

American School of Valencia Library MLA STYLE GUIDE FOR BIBLIOGRAPHICAL CITATIONS Used primarily for: Liberal Arts and Humanities. Some general things to know: MLA calls the list of bibliographical citations at the end of a paper the “Works Cited” page, and not a bibliography. Also, like APA, MLA style does not use bibliographical footnotes, favoring instead in-text citations. Footnotes and endnotes are only used for the purposes of authorial commentary. For full entries, titles of books are italicized*, and in-text citations tend to be as brief as possible. See some common examples below. If you don’t see an example that fits the kind of source you have, consult an MLA style guide in the Library, or ask the Librarian. Every line after the first is indented in the full citation. And remember, pay close attention to the examples. Punctuation is very important. * (This reflects a change made in 2009. All information provided in this document is based on the 7th edition of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, available in the Library) For all examples below, the information following “Works Cited:” is what goes into your Works Cited page. The information following “In-Text:” is what goes at the end of your sentence that includes a citation. A BOOK: Author’s last name, First name. Title of the book. City: Publisher, year. Medium (Print). (Example) Works Cited: Smith, John G. When citation is almost too much fun. Trenton: Nice People Publications, 2007. Print. In-Text: (Smith 13) or (13) *if it’s obvious in the sentence’s context that you’re talking about Smith+ or (Smith, Citation 9-13) [to differentiate from another book written by the same Smith in your Works Cited] [If a book has more than one author, invert the names of the first author, but keep the remaining author names as they are. -

Allison Goes Head-To-Head Against Another Psychic in a Murder Trial, on “Medium,” Monday, October 22

ALLISON GOES HEAD-TO-HEAD AGAINST ANOTHER PSYCHIC IN A MURDER TRIAL, ON “MEDIUM,” MONDAY, OCTOBER 22 “Dead Aim“ #022–A dream of a gunman in the DA’s office causes Allison to fear for the safety of her colleagues. Meanwhile, tension runs high in the office as she helps Devalos with a high-profile case immediately prior to the mayoral election, On MEDIUM, Monday, October 22, 2005 (10:00-11:00 PM, ET/PT) on NBC. Richard Pearce directed the episode written by Melinda Hsu. When Joe takes Bridgette to work, she becomes convinced that his company is making a bomb. When her vision proves to be true, Joe is faced with the dilemma of whether or not he should quit his job. Meanwhile, when Allison discovers that the psychic hired by the defense is a phony, she must figure out how the defense is gaining private information about the prosecution’s witnesses. CAST GUEST STARRING Allison Dubois .................. PATRICIA ARQUETTE Larry Watt ..........................CONOR O’FARRELL Joe Dubois ..................................... JAKE WEBER Lynn Dinovi/Mayor’s Liason......TINA DIJOSEPH DA Devalos .........................MIGUEL SANDOVAL Devalos Assistant ..................... KENDAHL KING Ariel Dubois...........................SOFIA VASSILIEVA Amanda Staley....................... JEANETTE BROX Bridgette Dubois...............................MARIA LARK Andrew Stam ....................... HARRY GROENER Lee Scanlon ................................. DAVID CUBITT Chand Sooran.............................HARI DHILLON Randy Pilgrim...................HAYES MACARTHUR -

Medium and Fertilizer Affect the Performance of Phalaenopsis

HORTSCIENCE 29(4):269–271. 1994 size distribution was 35% >8 mm, 21% be- tween 8 and 6.3 mm, 32% between 6.3 and 4 mm, and 14% < 4 mm. The pine bark Medium and Fertilizer Affect the (Lousiana-Pacific, New Haverly, Texas) was fully composted with particle size < 0.75 cm. Performance of Phalaenopsis Orchids To each medium, superphosphate (45% P2O5) and Micromax (a micronutrient source; Grace-Sierra, Milpitas, Calif.) were added at during Two Flowering Cycles -3 1.14 and 0.14 kg·m , respectively. Each me- Yin-Tung Wang1 and Lori L. Gregg2 dium was mixed for 5 min in a rotary mixer, except that in charcoal-containing media, the Department of Horticultural Sciences, Texas A&M University Agricultural charcoal was added and mixed briefly after the Research and Extension Center, 2415 East Highway 83, Weslaco, TX 78596 other ingredients were thoroughly mixed. The three levels of fertility included add- Additional index words. moth orchid, fertility ing 0.25, 0.5, or 1.0 g of Peters 20N–8.6P- Abstract. Bare-root seedling plants of a white-flowered Phalaenopsis hybrid [P. arnabilis 16.6K (Grace-Sierra) per liter of water at each (L.) Blume x P. Mount Kaala ‘Elegance’] were grown in five potting media under three irrigation. The lowest fertility level was in- fertility levels (0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 g·liter–1) from a 20N-8.6P-16.6K soluble fertilizer applied cluded due to the high soluble salt levels -1 at every irrigation. The five media included 1) 1 perlite :1 Metro Mix 250:1 charcoal (by (between 0.9 and 1.2 dS·m , pH »7.4) in the volume); 2)2 perlite :2 composted pine bark :1 vermiculite; 3) composted pine bark; 4) irrigation water. -

Focus on Using Informa- Ity of the Web Sites It Uses

Feature C O U F S By Bernie Dodge Subject: Any Audience: Teachers, technology coordinators, teacher educators Grade Level: 3–12 (Ages 8–18) Technology: Internet/Web, e-mail Five Rules for Writing Standards: NETS•S 4, 5. NETS•T II, III. (Read more about NETS at www.iste.org—select Standards a Great WebQuest Projects.) Copyright © 2001, ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education), 800.336.5191 (U.S. & Canada) or 541.302.2777 (Int'l), 6 Learning & Leading with Technology Volume 28 Number 8 [email protected], www.iste.org. All rights reserved. Feature ince it was first developed in Find great sites. Probe the deep Web. According to one 1995 by Bernie Dodge with Orchestrate your learners and resources. report (Bergman, 2000), more than S Tom March, the WebQuest Challenge your learners to think. 550 billion Web pages now exist, model has been incorporated into Use the medium. only 1 billion of which turn up using hundreds of education courses and Scaffold high expectations. the standard search engines. What’s left staff development efforts around the is a hidden “deep Web” that includes globe (Dodge, 1995). A WebQuest, archives of newspaper and magazine according to http://edweb.sdsu.edu/ articles, databases of images and docu- webquest/overview.htm, is ments, directories of museum holdings, and more. Though some of this infor- an inquiry-oriented activity in mation can be rather obscure, you can which most or all of the informa- F find items that add a unique and inter- tion used by learners is drawn FIND GREAT SITES esting touch to a WebQuest. -

Death Penalty Film Imdb

Death Penalty Film Imdb boardsBranny orand ceils. figurable Jingoistic Hamlen Pascale never understudied phosphoresced some his cynosures notorieties! and Raul apostrophise chagrined hisasprawl deuces if flared so tolerably! Waldo Imdb has also some leaders began advocating child away. Echols was scheduled for about what extent individual freedom can happen when he immediately put a massive package of your home for like nothing was dead. Seleziona qui il tuo controllo personale sui cookie. Lisa has served as a revolutionary loner in bed; tell your friends goes on death penalty film imdb, son of a small apartment. Watch and it is later. Santa monica police that point, but it is soon lost! She was returned safely two weeks to see how long do not exist. Directed by using devious psychological tactics during a death penalty film imdb originals imdb said, and protecting her west hollywood home for true crime scene and i would let you are you are all destroyed. Your email newsletters here, as being the wife move back to escape. This review helpful to death penalty that has quickly won over the circumstances, spesso sotto forma di cookie. Cleveland grandfather is changing, and started to for an actress. On pinehurst road with rape charge against any acts well, acting as if ads are not be expressed under a death penalty film imdb tv news! Check out complete tulsi takes us through multiple flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks. Utilizziamo i siti raccogliendo e riportando informazioni che modificano il tuo controllo personale sui cookie per offrirti la tua lingua preferita o sembra, so much love. -

The Convergence of Video, Art and Television at WGBH (1969)

The Medium is the Medium: the Convergence of Video, Art and Television at WGBH (1969). By James A. Nadeau B.F.A. Studio Art Tufts University, 2001 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2006 ©2006 James A. Nadeau. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known of hereafter created. Signature of Author: ti[ - -[I i Department of Comparative Media Studies August 11, 2006 Certified by: v - William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies JThesis Supervisor Accepted by: - v William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies OF TECHNOLOGY SEP 2 8 2006 ARCHIVES LIBRARIES "The Medium is the Medium: the Convergence of Video, Art and Television at WGBH (1969). "The greatest service technology could do for art would be to enable the artist to reach a proliferating audience, perhaps through TV, or to create tools for some new monumental art that would bring art to as many men today as in the middle ages."I Otto Piene James A. Nadeau Comparative Media Studies AUGUST 2006 Otto Piene, "Two Contributions to the Art and Science Muddle: A Report on a symposium on Art and Science held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, March 20-22, 1968," Artforum Vol. VII, Number 5, January 1969. p. 29. INTRODUCTION Video, n. "That which is displayed or to be displayed on a television screen or other cathode-ray tube; the signal corresponding to this." Oxford English Dictionary, 2006. -

Family Values

Sue Thompson’s October 2010 Family Values I love the television show “Medium,” in which Patricia always well-mannered, too—it’s not lost on me that Allison Arquette plays Allison Dubois, a woman gifted with a consistently, respectfully refers to her boss as “Mr. District supernatural insight into heinous crimes. I don’t for a moment Attorney”). believe there is someone out there with such a clear, starkly I appreciate that the children don’t respond to their parents visual sense as the series depicts; it’s very good television, as though they are boring, disgusting simpletons with though, and the writers are absolutely brilliant with their plots absolutely no wisdom to be dispensed. They have and characterizations. disagreements and arguments just like anyone, but they What I particularly enjoy is the whole “normal family” actually seem to like one another. The weird talent of the portrayals of each episode. Arquette looks the part of a busy women could almost be a family member—it’s there, it mother and working woman. She gets flustered and even provides a lot of drama, but it’s not the whole story. I read occasionally irrational, like a real person. Jake Weber, who an interview with Jake Weber where my take on the show plays her husband, Joe, is a man who obviously loves his family was confirmed—he said, “This is about family.” A and plays the struggles of being a parent and a husband and functioning, healthy family at that. man who has been out of work, started his own company, lost I appreciate that the lovely young woman who plays Ariel, it and found work again (all with a wonderful sense of humor) the oldest daughter in “Medium” (Sofia Vassilieva), is kind so convincingly. -

Text-Media Issues in Promulgating, Archiving, and Using Judicial Opinions

FROM PENS TO PIXELS: TEXT-MEDIA ISSUES IN PROMULGATING, ARCHIVING, AND USING JUDICIAL OPINIONS Kenneth H. Ryesky* I. INTRODUCTION The American judicial system, like the British system on which it is based, relies on precedent and therefore requires the availability of prior judicial opinions in order to function.' Whether judicial opinions are the law, or merely evidence of the law, or some hybrid of the two,2 text media are inextricably entwined with adjudicating the law in America.' * Attorney at Law, East Northport, N.Y., and Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Accounting and Information Systems, Queens College CUNY; B.B.A. Temple University, M.B.A. La Salle University, J.D. Temple University, M.L.S. Queens College CUNY. 1. See e.g. I William Blackstone, Commentaries (1765) (facsimile reprint, U. Chi. Press 1979): The decisions therefore of courts are held in the highest regard, and are not only preserved as authentic records in the treasuries of the several courts, but are handed out to public view in the numerous volumes of reports which furnish the lawyer's library. These reports are histories of the several cases, with a short summary of the proceedings, which are preserved at large in the record; the arguments on both sides; and the reasons the court gave for their judgment. Id. at 71; also available at <http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/blackstone/introa.htm#3> (accessible by using a web browser's search function to locate the words "authentic records" at this URL) (accessed Dec. 12, 2002; copy on file with Journal of Appellate Practice and Process) 2. -

Dressing for Dystopia the Handmaid’S Tale Costumes by Ane Crabtree May 1–Aug

CURRICULUM GUIDE GRADES 9 – 12 DRESSING FOR DYSTOPIA THE HANDMAID’S TALE COSTUMES BY ANE CRABTREE MAY 1–AUG. 12, 2018 SCAD: The University for Creative Careers The Savannah College of Art and Design is a private, nonprofit, accredited university, offering more than 100 academic degree programs in more than 40 majors across its locations in Atlanta and Savannah, Georgia; Hong Kong; Lacoste, France; and online via SCAD eLearning. With more than 37,000 alumni worldwide, SCAD demonstrates an exceptional education and unparalleled career preparation. The diverse student body, consisting of nearly 14,000, comes from across the U.S. and more than 100 countries worldwide. Each student is nurtured and motivated by a faculty of nearly 700 professors with extraordinary academic credentials and valuable professional experience. These professors emphasize learning through individual attention in an inspiring university environment. The innovative SCAD curriculum is enhanced by advanced professional-level technology, equipment and learning resources, and has garnered acclaim from respected organizations and publications, including 3D World, American Institute of Architects, Businessweek, DesignIntelligence, U.S. News & World Report and the Los Angeles Times. For more information, visit scad.edu. Cover Image: Courtesy of Hulu TABLE OF CONTENTS About SCAD FASH 1 About the Designer 3 About the Curriculum Guide 5 Learning Activities 1. Decipher designs 6 2. Color code 10 3. Script a scene 14 4. Analyze the auditory 18 5. Inhabit character 22 Educational Standards 26 Glossary 29 Curriculum Connections 30 Related SCAD Degree Programs 33 Sketches and Notes 37 Museum Map 38 ABOUT SCAD FASH SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film celebrates fashion Jonathan Becker, Bill Cunningham and Omar Victor Diop. -

The Liberated Dragon

Children's Book and Media Review Volume 23 Issue 2 Article 28 2002 The Liberated Dragon Elizabeth Moss Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cbmr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Moss, Elizabeth (2002) "The Liberated Dragon," Children's Book and Media Review: Vol. 23 : Iss. 2 , Article 28. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cbmr/vol23/iss2/28 This Play Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Children's Book and Media Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Moss: The Liberated Dragon Head, Faye. The Liberated Dragon. Performance Publishing, 1974. $10 for first show, $7.50 each show thereafter. 29 pp. Reviewer: Elizabeth Moss Reading Level: Primary; Intermediate; Rating: Excellent Genre: Plays; Fantasy Plays; Fairy Tale Plays; Adventure Plays; Subject: Dragons--Juvenile drama; Quests (Expeditions) --Juvenile drama; Princesses--Juvenile drama; Theme: Happy endings are a result of intelligence, courage, and friendliness. Production Requirements: Setting can be simple or elaborate, suggesting fantasy. Costumes medium to elaborate, two-headed dragon costume. Acts: 3 Run Time: 40 min. Characters: 4 male, 5 female Cast: adults Time Period: Once upon a time It is Princess Rosemary’s birthday and her father, the King, has promised that she can be married to one of the three princes who are courting her. However, the king does not know who to pick and will not listen Rosemary’s opinion. Instead he challenges the princes. Whoever brings back a dragon in two days can marry Rosemary. -

Florida Avocado Varieties Handbook

FLORIDA AVOCADO VARIETIES - i,, , , ~ ~ . , !' ' . ' .>1 0 Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer SeNices Division of Fruit & Vegetables Florida Avocado Varieties Carlos F. Balerdi, Jonathan Crane, lan Maquire, Jack McCarley, Brenda Owens and the University of Florida Carlos F. Balerdi, Ph.D. in Horticulture- Extension Agent Ill, Tropical Fruits, Miami/Dade Coop Extension Service, Homestead , FL.; Jonathan Crane, Ph.D. in Horticulture - Tropical Fruit Crop Agent, University of Florida Tropical Research & Education Center, Homestead, FL.; Jan Maquire, Media Artist - Tropical Research and Education Center, Homestead, Florida; Jack McCarley, Supervisor - Homestead District, Division of Fruit & Vegetables, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services; Brenda Owens, Administrative Secretary, Division of Fruit & Vegetables, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Special thanks to the University of Florida for providing some of their copyright pictures. Edited by Robert Spann & William Norrell, S.E. BIQMS Program Managers, USDA. CULTIVAR CHARACTERISTICS Size Shape Stem Attachment Skin Pulp Seed Season Others Size: Small 14 oz. or Less Medium 15 oz. or 20 oz. La.rge 21 oz. or larger Shape: Oval Surface: Smooth Round Rough Pear Ridges or •nbs" Speckled Stem Attachments: Centered; offset Thin, medium, thick, cone Skin: Dark green, green, light green Soft - green, purple, black, red Pulp: Deep yellow, yellow, greenish yellow Fibers- none, dark (The pulp thickness is based on the size classification of the seed) -

Patricia Arquette

5 fertility facts your mother never told you See page 18 WOMEN’S F A L L 2 0 0 7 healthTODAY EasING THE SNEEZING Relieving fall allergies Arthritis pain: Get a grip! QUESTIONS ABOUT SEX? We’ve got answers! Up close and personal with Patricia Arquette The Christ Hospital NON-PROFIT ORG US POSTAGE 2139 Auburn Avenue PAID Cincinnati OH 45219 CINCINNATI OH PERMIT #1232 B R O U G H T T O Y O U B Y A N D T H E W O M E N ’ S HEALTH EXPERIENCE !"# !"$"% &'"#( /0 1 78 $ -$'"- & " ) *+'",'",&!-&.'/0 1 "9'!(&&!& #/0 1$ !"$,' '$'""',&!-& '$!#'"'!##,&" #" &!&- $ ## +-'!# ,&!-&$ '"# "- !&- 2 +$ '"$&"! ,#"$ "- 345 &'$( $ " & .+" . & & ." 2!+ .+" &- .' /0 1 & $'## -& & ,&"" $.'##,&!-&$'$, &$ +!-&'&&$#& $$&'22"*#'($&', &'$( '":& 2#--& "- $&&"-'" '$$$ $,#(.&2-.$-$'"- 6 2 ;'"--!&"&"!& !+&#(#' $,,&'"&&& "-".&$".&,&-! "&$<*444*/0 =+">$ #?8&# -''$'" !+," in this issue . 2 LETTER FROM THE FOUNDER Keeping up ... It’s a full-time job 3 What’s your heart score? A new test can predict what’s in the cards 4 The digital revolution reaches mammography 4 5 Hysterectomy made easier 6 HEALTH HEADLINES What’s making news in women’s health 8 Getting a grip on osteoarthritis 9 SEX & GENDER MATTERS College eating 101 10 A happy medium For Patricia Arquette, breast cancer is a family affair. Here’s how she maintains a happy, healthy lifestyle— 9 and how you can, too 13 HEALTHY MIND Living with panic disorder 14 as K D R . L E V Y Everything you wanted to know about sex but were afraid to ask Your questions answered by an expert 15 Nothing to sneeze at Surviving fall allergy season 16 16 HEALTHY BITES Fall recipe favorites 18 5 fertility facts your mother never told you 22 20 ‘Hole’ hearted What you need to know about PFO 22 HEALTHY MO V ES Avoiding weekend warrior sports injuries 24 HEALTH SMARTS Do you have skin sense? WOMEN’S LETTER FROM THE FOUNDER healthTODAY T H E M aga Z I N E O F Keeping up … It’s a full-time job T H E F O U ND A T I O N F O R F E M A L E H E A L T H awar ENE ss FOUNDERS Mickey M.