Fung Business Intelligence Centre [email protected] New York: 646.839.7017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

151016 CB China Power of Retailing 2015 CN.Docx

China Power of Retailing 2015 China Power of Retailing 2015 1 Foreword 2015 has witnessed the recovery of a global economy and the gradual stabilization of a real economy in China. While the Eurozone economy continues to improve, the differentiation among its economies remains noticeable. “Abeconomics” throws Japan into deep recession. The United States of America, as the only exception, enters the trajectory of a strong recovery and the US dollar has appreciated sharply against other major world currencies. Its well-anticipated rise in interest rate in the fourth quarter forebodes an accelerated devaluation of currencies in most emerging economies. As a result, the pressure on devaluating RMB is mounting. With a slowed growth rate, the Chinese economy has arrived at the stage of new normal. The YoY growth for the first half of the year lingers around 7%, hindered by the deceleration of the three engines that used to propel GDP growth – a sluggish export, a slow growth in investment and a domestic consumption that continues to fall behind expectation. Although the growth rate of the total retail of consumer goods has dropped, it has far outpaced the domestic industrial growth. With the consumer confidence seeing constant improvement that will further free up consumption potential, consumption is expected to continue pulling the economy in the future. A continued fall in oil prices has offset the inflationary pressure, curbing the inflation at a lower level to make room for executing a lax monetary policy. To further boost investment and consumption, and reduce enterprise financing costs, the government has gradually redirected its macro economy from “stabilize growth and adjust structure” to “ensure growth,” making the lowering of interest rate and reserve ratio possible in the second half of the year. -

Global Powers of Retailing 2019 Contents

Global Powers of Retailing 2019 Contents Top 250 quick statistics 4 Global economic outlook 5 Top 10 highlights 8 Global Powers of Retailing Top 250 11 Geographic analysis 19 Product sector analysis 23 New entrants 27 Fastest 50 30 Study methodology and data sources 35 Endnotes 39 Contacts 41 Welcome to the 22nd edition of Global Powers of Retailing. The report identifies the 250 largest retailers around the world based on publicly available data for FY2017 (fiscal years ended through June 2018), and analyzes their performance across geographies and product sectors. It also provides a global economic outlook, looks at the 50 fastest-growing retailers, and highlights new entrants to the Top 250. Top 250 quick statistics, FY2017 Minimum retail US$4.53 US$18.1 revenue required to be trillion billion among Top 250 Aggregate Average size US$3.7 retail revenue of Top 250 of Top 250 (retail revenue) billion 5-year retail Composite 5.7% revenue growth net profit margin 5.0% Composite (CAGR from Composite year-over-year retail FY2012-201 2.3% return on assets revenue growth 3.3% Top 250 retailers with foreign 23.6% 10 operations Share of Top 250 Average number aggregate retail revenue of countries where 65.6% from foreign companies have operations retail operations Source: Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited. Global Powers of Retailing 2019. Analysis of financial performance and operations for fiscal years ended through June 2018 using company annual reports, Supermarket News, Forbes America’s largest private companies and other sources. 4 Global economic outlook 5 Global Powers of Retailing 2019 | Global economic outlook The global economy is currently at a turning point. -

GFSI : Overview and GFSI : Overview and Comparaison of Comparaison Of

GFSI : Overview and comparaison of schemes CMC May 5, 2011 GFSI Background In 2000….. ¾ FdFood saftfetycrises ¾ Profileration of individual retailer schemes ¾ Burden to suppliers and producers due to frequent audits ¾ Lack of efficiency and high costs in the food supply chain Global Food Safety Initiative ¾ GFSI lhdlaunched at the CIES AlAnnual Congress in 2000, following a directive from the food business CEOs. ¾ Food Safety was then, and is still, top of mind with consumers. Consumer trust needs to be strengthened and maintained, while making the suppl y chain safer. ¾ Managed by The Consumer Goods Forum GFSI managed by The Consumer Goods Forum ¾ An independent global parity‐based Consumer Goods network ¾ Over 650 Members ¾ Representing 70 countries ¾ Over 3 continents Paris, HQ Washington D.C. Tokyo €2.1 trillion THE CONSUMER GOODS FORUM BOARD OF DIRECTORS MANUFACTURER RETAILER COLLEGE COLLEGE 25 25 CEOsCOs CEOsCOs Retailer College Manufacturer College « Safe Food for Consumers Everywhere » GFSI Mission Driving continuous improvement in food safety to strengthen consumer confidence worldwide GFSI Objectives Reduce food safety risks Manage cost GFSI Develop competencies Knowledge exchange and capacity building and networking How does GFSI work? ¾ Benchmarks existing food safety schemes, including pre‐farm gate schemes against the GFSI Guidance Document. ¾ Determines whether a scheme is equivalent to the Guidance Document requirements. ¾ Helps and encourages food safety stakeholders to share knowledge and strategy for food safety and to develop best food safety practice in a common global framework. What GFSI Does NOT Do ¾ Make policy for retailers or manufacturers ¾ Make policy for standard owners ¾ Undertake any accreditation or certification activities ¾ Have involvement with an area outside the scope of food safety i.e. -

Global Powers of Retailing Top 250, FY2015

Global Powers of Retailing 2017 | Top 250 Global Powers of Retailing Top 250, FY2015 FY2015 FY2015 Parent Parent FY2010- FY2015 FY2015 company/ company/ # 2015 Retail Retail group group Countries Retail revenue Country revenue revenue¹ net income¹ of revenue rank Company of origin (US$M) (US$M) (US$M) Dominant operational format operation CAGR² 1 Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. US 482,130 482,130 15,080 Hypermarket/Supercenter/Superstore 30 2.7% 2 Costco Wholesale Corporation US 116,199 116,199 2,409 Cash & Carry/Warehouse Club 10 8.3% 3 The Kroger Co. US 109,830 109,830 2,049 Supermarket 1 6.0% 4 Schwarz Unternehmenstreuhand KG Germany 94,448 94,448 n/a Discount Store 26 7.4% 5 Walgreens Boots Alliance, Inc. US 89,631 103,444** 4,279 Drug Store/Pharmacy 10 5.9% (formerly Walgreen Co.) 6 The Home Depot, Inc. US 88,519 88,519 7,009 Home Improvement 4 5.4% 7 Carrefour S.A. France 84,856 87,593 1,247 Hypermarket/Supercenter/Superstore 35 -3.1% 8 Aldi Einkauf GmbH & Co. oHG Germany 82,164e 82,164e n/a Discount Store 17 8.0% 9 Tesco PLC UK 81,019 82,466 535 Hypermarket/Supercenter/Superstore 10 -2.3% 10 Amazon.com, Inc. US 79,268 107,006 596 Non-Store 14 20.8% 11 Target Corporation US 73,785 73,785 3,363 Discount Department Store 1 2.3% 12 CVS Health Corporation US 72,007 153,290 5,239 Drug Store/Pharmacy 3 4.7% 13 Metro Ag Germany 68,066** 68,066** 821 Cash & Carry/Warehouse Club 31 -2.5% 14 Aeon Co., Ltd. -

SUSTAINABILITY, SOCIAL MEDIA… and the FUTURE of RETAIL

THE COCA-COLA RETAILING RESEARCH Councils SUSTAINABILITY, SOCIAL MEDIA… AND THE FUTURE OF RETAIL Global Retail Summit London, August 2012 The first Coca-Cola Retailing Research Council was formed in 1978 in North America to help retail customers address industry issues through organized discussion and commissioned research. Today, the Company sponsors six Councils throughout the world: North America, NACS North America, Europe, Asia, Latin America, and Eurasia & Africa. Each Council is comprised of up to 20 retail leaders and non-voting Coca-Cola system executives. Widely considered to be among the industry’s most prestigious retail think tanks, the Coca-Cola Retailing Research Councils have published more than 50 proprietary studies on issues ranging from shopper insights and new market dynamics to technology, innovation and social media. THIS PUBLIcatION IS A COLLECTION OF PAPers PRODUCED FROM PresentatIONS at GLOBAL RetaIL SUMMIT. Panel DIscUSSIONS DURIng THE SUMMIT WERE NOT RECORDED. © 2012 THE COCA-COla EXPOrt CORPOratION, UNDER THE AUSPIces OF THE COCA-COla RetaILIng ResearcH COUncIls CONTENTS FOREWORD FACING UP TO NEW REALITIES Muhtar Kent PAGE 2 SUSTAINABILITY THE CHALLENGE FOR RETAILERS HRH Prince Charles PAGE 4 WELCOME TO THE NEW NORMAL Lord Deben PAGE 8 THE QUEST FOR CHANGE Carter Roberts PAGE 12 WHY LESS HAS TO MEAN MORE Dr Jason Clay PAGE 16 SOCIAL MEDIA BACK TO THE FUTURE? James Quarles PAGE 22 BE YOURSELF… SIMPLY FLAWSOME Wendy Clark PAGE 28 IT PAYS TO TALK. BUT KEEP IT RELEVANT… AND HONEST Richard Reed PAGE 30 THE FUTURE OF RETAILING HOW TO PREPARE FOR THE ‘PERFECT STORM’ Mark Price PAGE 34 SUMMARY THE PROMISE OF SUSTAINABLE GROWTH PAGE 38 LIST OF MEMBERS PAGE 40 CCRRC Global Retail Summit RepoRt FOREWORD FACING UP TO NEW REALITIES Muhtar Kent Chairman and Chief Executive Officer The Coca-Cola Company ince 1978, the Coca-Cola Retailing This is why I am convinced that sustaina- Research Council has generated over bility and social media will forever be con- 40 extensive, proprietary studies on nected at the hip. -

For Immediate Release

Press Release For Immediate Release China Resources Enterprise, Limited Announced 2002 Interim Results Restructuring Efforts Start to Pay Off (Hong Kong, September 4, 2002) China Resources Enterprise, Limited (SEHK Code: 0291), together with its subsidiaries (collectively “The Group”), announced its interim results for the six months ended June 30, 2002 today and reported an unaudited consolidated turnover and profit attributable to shareholders of HK$12,933 million and HK$720 million respectively, representing a 7.2% increase and an 8.6% decrease over the same period of last year. Excluding the profit of HK$59.1 million from the disposal of a 25.5% stake in China Resources (Shenyang) Sanyo Compressor Co., Ltd. in the first half of 2001, profit attributable to shareholders for the six months ended June 30, 2002 declined slightly by just 1.2% over the same period of last year. Earnings per share, based on a weighted average number of shares, was HK$0.35 compared with HK$0.39 for the first half of 2001. The Board has declared an interim dividend for the year ending December 31, 2002 of HK 9 cents per share which will be payable on or about November 1, 2002. Mr. Frank Ning, the Chairman of China Resources Enterprise, Limited said, “The Group’s strenuous efforts in restructuring its distribution businesses into a more refined and focused ‘retail-led distribution’ direction are gradually paid off. This is evident from the earnings stability in the first half of 2002 in the absence of any significant property development and banking profits. We are confident that our retail-led distribution model will drive future growth and thus earnings of the Group will be more recurrent.” Among the different business divisions, earnings of the Group’s Petroleum and Chemical operation doubled due to higher wholesaling margin of petroleum, turnaround of chemicals distribution business as well as continued growth of the local retail business. -

2020-Your-Choice.Pdf

Red Hot Rewards of Your Choice With the year-round “Red Hot Rewards of Your Choice” Up to programme, you can allocate your extra RewardCash among the RewardCash rebate, 6 spending categories to earn rewards faster! 2.4% year-round Red Hot Rewards of Your Choice From 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020, the 1-year1 programme let you earn up to 6X RewardCash2 (which is equivalent to 2.4% RewardCash rebate) at a wide range of merchants all year round. You can allocate your extra 5X RewardCash among the 6 spending categories3 of Dining, Entertainment, Home, Lifestyle, Mainland China and Macau Spending and Overseas Spending according to your spending habits. You can enjoy the extra RewardCash for your first HK$100,000 eligible spending, so that you can earn rewards even faster. Three simple steps to start earning extra RewardCash Call hotline 8228 3308 or Visit www.hsbc.com.hk/rewards to register Allocate extra 5X RewardCash to your preferred spending categories Dining Spending at dining outlets in Hong Kong4 Entertainment4 Selected merchants: AMC Pacific Place, Broadway Circuit, CGV Cinemas, Festival Grand Cinema, Golden Harvest Cinemas, Grand Windsor Cinema, MCL Cinemas, STAR Cinema, the sky, UA Cinemas, CEO, Neway and RedMR Home4 Selected merchants: 759 Store, BROADWAY, HKTVmall, Mannings, PARKnSHOP and Wellcome Supermarket Lifestyle4 Selected merchants: AEON, agnès b, APiTA, GigaSports, GU, SOGO and UNIQLO Mainland China and Spending in Mainland China and Macau4 Macau Spending5 Overseas Spending5 Overseas spending4 Spend with your HSBC credit card and earn up to 2.4% RewardCash rebate all year round! Y9-U1-CAMH0206/FOD/E How to earn up to 2.4% RewardCash rebate Lifestyle Department Stores AEON, AEON STYLE, AEON SUPERMARKET, AEONBODY, APiTA, Bento Express by Simply allocate your extra 5X RewardCash multiplier to a single frequently used spending category in the “Red AEON, Chinese Arts & Crafts, Citistore, La Bohéme Bakery, Living PLAZA by AEON, Hot Rewards of Your Choice” programme. -

Businesses 3/31/18 DBA Name #1 a LIFESAFER of COLORADO, LLC

All Businesses 3/31/18 DBA Name #1 A LIFESAFER OF COLORADO, LLC 0.1 AFFORDABLE HAULING & MOVING 0.5 HAULING 1 SHAMROCK'S FINEST LANDSCAPES 1 STORY LLC 1 TO 1 REAL ESTATE 1-800 CONTACTS INC 1-800 RADIATOR 1-800-FLOODED 101 PARK AVENUE PARTNERS, INC 107 S GRAND LLC 13TH STREET BARBER SHOP 1A SMART START INC 21ST CENTURY BUILDERS 360i CERTIFIED HOME INSPECTIONS 3D SYSTEMS INC 3D'S CIGARS 3FORM, LLC 3M COMPANY 4 RIVERS EQUIPMENT HOLDINGS, LLC 4FRONT ENGINEERED SOLUTIONS 4LIFE RESEARCH CSA LLC 4TH ST BARBER AND STYLING CENTER 5 STORY LLC 50/OFF WEEKEND WAREHOUSE 5B COMPANY LLC 7-ELEVEN STORE 20638J 7-ELEVEN STORE 23811A 7-ELEVEN STORE 32990 A 7TH ST STATION LLC 80/TWENTY WINES 800-FLOWERS A & A QUALITY APPLIANCE A + MOBILE AUTO SERVICE LLC A 1 BARRICADE AND SIGN INC A 1 ELECTRIC SERVICE INC A 1 FLOORING A 1 HANDYMAN SERVICE A AARDVARK ROOFING INC A AFFORDABLE DISPOSAL OF PUEBLO INC A AND A CHIROPRACTIC CENTER A AND B EMBROIDERY A AND B HEATING A AND B SEPTIC SERVICE INC A AND E USED FURNITURE A AND K ROOFING AND GUTTERS A AND M PEST AND TERMITE CONTROL A AND R CONSTRUCTION LLC A AND S STUCCO A B AND C ENTERPRISES INC A BETTER DAYCARE AT DEBBIES A BETTER TREE SERVICE A BUDGET LANDSCAPE A CHILD'S EXPERIENCE LLC A COUNTRY CANINE GROOMING & PET SPA A Cut Above the Rest A CUTTING EDGE TREE SERVICE A GREAT BOOK SHOP A HEALING TOUCH A NATURAL SOLUTION A NEW YOU A P FOOT AND ANKLE SPECIALTISTS PC A PERFECT 10 A PLUS AUTO GLASS A PLUS REGIONAL HEATING AND COOLING A QUALITY ELECTRIC SERVICES A REAL MUFFLER AND BRAKE A SHED USA A SUPERIOR SERVICE LLC A T AND T CORP A T AND T MOBILITY A TIN MAN HEATING AND AIR CONDITIONING LLC A TOUCH OF CLASS A VAR ELECTRIC INC A&B MECHANICAL A&E SCREEN PRINTING COMPANY LLC A&R SERVICES A&S CONSTRUCTION CO A'VIANDS LLC #E1561 A-GLOBAL DISPOSAL A-JEN LLC A-MAY-ZING BUILDERS INC A. -

Retailers Outside the United States

Directory of Foreign Retailer Web Sites Here are links to the Web sites of more than 235 foreign retailers (with their home countries noted). These firms represent all facets of retailing. For some foreign retailers, their home language appears (rather than English). [Note: Web site URLs may change. PLEASE notify us at [email protected] if you find a broken link. Thanks!] Adeo Groupe – France Aeon Jusco – Japan Aldi Einkauf – Germany Alliance Boots – Great Britain Arcadia Group – Great Britain Arcs Co. – Japan ASDA – Great Britain Associated British Foods – Great Britain Auchan – France Axel Johnson AB – Sweden Bailian Group – China Bauhaus – Germany Beck and Call – Great Britain Beisia Group Co., Ltd. – Japan Belle International Holdings Limited – China Benetton – Italy Best Denki – Japan BGF Retail Co., Ltd. – South Korea Bic Camera Inc. – Japan Big Star – Poland BIM – Turkey Blackwell’s Bookshops – Great Britain Blue Square – Israel Body Shop – Great Britain Bompreco – Brazil Boots – Great Britain Budgens – Great Britain Buyers Edge – Australia © by Joel R. Evans, Barry Berman, and Patrali Chatterjee C&A – Netherlands Canadian Tire – Canada Carrefour – France Casino – France Castorama – France Cathay Photo – Singapore Celio – France Cencosud S.A. – Chile Central Group – Thailand Chapters Online – Canada China Resources Vanguard Co. – China Chow Tai Fook Jewellery Group Limited – Hong Kong Coles Supermarkets – Australia Colruyt Group – Belgium Comercial Mexicana – Mexico Compagnie Financiåre Richemont SA -- Switzerland Compass -

Drive China's Food Retail Sector

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 6/26/2019 GAIN Report Number: CH196010 China - Peoples Republic of Retail Foods Smart Consumers and ‘New Retail’ drive China’s food retail sector Approved By: Lindsay Malecha Prepared By: ATO Guangzhou Report Highlights: China’s retail sector recorded $5.4 trillion in sales revenue in 2017, a 10 percent increase from 2016, with similar strong growth expected to have happened in 2018. Driven by its huge population, urbanization, and the rising per capita disposable income of the growing middle class, China’s demand for imported consumer-oriented food products is expected to grow at a steady pace. Chinese consumers’ demand for convenience is driven by busy lifestyles and facilitated by far- reaching digitalization. In 2018, China’s import of consumer-oriented food products reached approximately $45 billion, up 18 percent from 2017. Data-driven ‘new retail’ formats combining online and offline (O2O) have a firm footing and are expanding rapidly and creating new competition and challenges for traditional retailers. Increased tariffs on U.S. products have some retailers looking for substitute products. Opportunities exist for fresh and dried fruit, beef, dairy, seafood, nuts, pork and other products. Post: Beijing ATO increased 28 percent from the previous year, with similar Executive Summary: strong growth expected to have occurred in 2018. Urban In 2018, China’s import of consumer-oriented food households’ food expenditures account for one third of the products reached approximately $45 billion, up 18 total. -

China: Retail Foods

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 12/28/2017 GAIN Report Number: GAIN0036 China - Peoples Republic of Retail Foods Increasing Change and Competition but Strong Growth Presents Plenty of Opportunities for U.S. Food Exports Approved By: Christopher Bielecki Prepared By: USDA China Staff Report Highlights: China remains one of the most dynamic retail markets in the world, and offers great opportunities for U.S. food exporters. Exporters should be aware of several new trends that are changing China’s retail landscape. Imported food consumption growth is shifting from China’s major coastal metropolitan areas (e.g., Shanghai; Beijing) to dozens of emerging market cities. China is also experimenting with new retail models, such as 24-hour unstaffed convenience stores and expanded mobile payment platforms. E-commerce sales continue to grow, but major e-commerce retailers are competing for shrinking numbers of new consumers. We caution U.S. exporters not to consider China as a single retail market. Over the past 10 years, the Chinese middle-class has grown larger and more diverse, and China has become a collection of 1 niche markets separated by geography, culture, cuisine, demographics, and commercial trends. Competition for these markets has become fierce. Shanghai and the surrounding region continues to lead national retail trends, however Beijing and Guangzhou are also important centers of retail innovation. Chengdu and Shenyang are two key cities leading China’s economic expansion into international trade and commerce. -

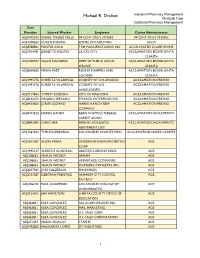

Additional Case Information

Michael R. Drobot Industrial Pharmacy Management MediLab Corp California Pharmacy Management Case Number Injured Worker Employer Claims Administrator ADJ7472102 ISMAEL TORRES VALLE 99 CENT ONLY STORES 99 CENT ONLY STORES ADJ1308567 CURTIS RIGGINS EMPIRE DISTRIBUTORS ACCA ADJ8768841 MARTIN AVILA TRM MANUFACTURING INC ACCELERATED CLAIMS IRVINE ADJ7014781 JEANETTE WILSON LA COUNTY ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA CLARITA ADJ7200937 SUSAN NAVARRO DEPT OF PUBLIC SOCIAL ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA SERVICE CLARITA ADJ8009655 MARIA PAEZ RUSKIN DAMPERS AND ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA LOUVERS CLARITA ADJ1993776 ROBERTA VILLARREAL COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ1993776 ROBERTA VILLARREAL COUNTY OF LOS ACCLAMATION FRESNO ANGELES/DPSS ADJ7117844 TOMMY ROBISON CITY OF MARICOPA ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ8162473 ONORIO SERRANO ESPARZA ENTERPRISES INC ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ8420600 JORGE LOZANO HARRIS RANCH BEEF ACCLAMATION FRESNO COMPANY ADJ8473212 DAREN HANDY KERN SCHOOLS FEDERAL ACCLAMATION SACRAMENTO CREDIT UNION ADJ8845092 CHAO HER FRESNO MOSQUITO ACCLAMATION SACRAMENTO ABATEMENT DIST ADJ1361532 THELMA JENNINGS LOS ANGELES COUNTY/DPSS ACCLAMATION SANTA CLARITA ADJ1611037 ALICIA MORA ANDERSON BARROWS METALS ACE CORP ADJ1995137 ALBERTO GUNDRAN ABLESTIK LABORATORIES ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY AMPAM ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY AMPAM RCR COMPANIES ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY PLUMBING CONCEPTS INC ACE ADJ2237965 JOSE CALDERON FMI EXPRESS ACE ADJ2353287 DEBORAH PRENTICE ANAHEIM CITY SCHOOL ACE DISTRICT ADJ246218 PAUL LIGAMMARI LOS ANGELES COLLEGE OF ACE CHIROPRACTIC