Copyright by Aniruddhan Vasudevan 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name

List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 1 Kanchipuram 1 Kanchipuram 1 Angambakkam 2 Ariaperumbakkam 3 Arpakkam 4 Asoor 5 Avalur 6 Ayyengarkulam 7 Damal 8 Elayanarvelur 9 Kalakattoor 10 Kalur 11 Kambarajapuram 12 Karuppadithattadai 13 Kavanthandalam 14 Keelambi 15 Kilar 16 Keelkadirpur 17 Keelperamanallur 18 Kolivakkam 19 Konerikuppam 20 Kuram 21 Magaral 22 Melkadirpur 23 Melottivakkam 24 Musaravakkam 25 Muthavedu 26 Muttavakkam 27 Narapakkam 28 Nathapettai 29 Olakkolapattu 30 Orikkai 31 Perumbakkam 32 Punjarasanthangal 33 Putheri 34 Sirukaveripakkam 35 Sirunaiperugal 36 Thammanur 37 Thenambakkam 38 Thimmasamudram 39 Thilruparuthikundram 40 Thirupukuzhi List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 41 Valathottam 42 Vippedu 43 Vishar 2 Walajabad 1 Agaram 2 Alapakkam 3 Ariyambakkam 4 Athivakkam 5 Attuputhur 6 Aymicheri 7 Ayyampettai 8 Devariyambakkam 9 Ekanampettai 10 Enadur 11 Govindavadi 12 Illuppapattu 13 Injambakkam 14 Kaliyanoor 15 Karai 16 Karur 17 Kattavakkam 18 Keelottivakkam 19 Kithiripettai 20 Kottavakkam 21 Kunnavakkam 22 Kuthirambakkam 23 Marutham 24 Muthyalpettai 25 Nathanallur 26 Nayakkenpettai 27 Nayakkenkuppam 28 Olaiyur 29 Paduneli 30 Palaiyaseevaram 31 Paranthur 32 Podavur 33 Poosivakkam 34 Pullalur 35 Puliyambakkam 36 Purisai List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 37 -

The Legal, Colonial, and Religious Contexts of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health in India Tanushree Mohan Submitted in Partial Fulfi

The Legal, Colonial, and Religious Contexts of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health in India Tanushree Mohan Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in Women’s and Gender Studies under the advisement of Nancy Marshall April 2018 © 2018 Tanushree Mohan ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Nancy Marshall, for offering her constant support throughout not just this thesis, but also the duration of my entire Women and Gender Studies Major at Wellesley College. Thank you for all of your insightful comments, last minute edits, and for believing in my capabilities to do this thesis. Next, I would like to thank the seven people who agreed to be interviewed for the purposes of this thesis. Although I can only refer to you as Interviewees A, B, C, D, E, F and G, I would like to state that I am very grateful to you for your willingness to trust me and speak to me about this controversial topic. I would also like to thank Jennifer Musto, whose seminar, “Transnational Feminisms”, was integral in helping me formulate arguments for this thesis. Thank you for speaking to me at length about this topic during your office hours, and for recommending lots of academic texts related to “Colonialism and Sexuality” that formed the foundation of my thesis research. I am deeply grateful to The Humsafar Trust, and Swasti Health Catalyst for providing their help in my thesis research. I am also thankful to Ashoka University, where I interned in the summer of 2016, and where I was first introduced to the topic of LGBTQIA mental health, a topic that I would end up doing my senior thesis on. -

Groundwater Quality Investigation in Udayarpalayam Taluk, Ariyalur District, Tamilnadu, India

International Letters of Chemistry, Physics and Astronomy Online: 2015-07-01 ISSN: 2299-3843, Vol. 53, pp 79-89 doi:10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILCPA.53.79 CC BY 4.0. Published by SciPress Ltd, Switzerland, 2015 GROUNDWATER QUALITY INVESTIGATION IN UDAYARPALAYAM TALUK, ARIYALUR DISTRICT, TAMILNADU, INDIA K. G. Sekar*, K. Suriyakala Department of Chemistry, National College, Tiruchirappalli-620001 E-mail address: [email protected] Keywords: Groundwater, Potability, UdayarpalyamTaluk, AriyalurDistrict, Physicochemical Parameters, Tamilnadu. ABSTRACT. Ariyalur is one of the districts in Tamilnadu it is rich in limestone resource. A study on geochemical characterization of ground water and its suitability for drinking purposes was carried out. Twenty five groundwater samples were collected from bore wells and open wells during Pre monsoon seasons of 2014. Groundwater is the main principle source for drinking, irrigation water and other activities in our study area. It is an indispensable source of our life. The problem of groundwater quality obtains high importance in this present-day, whether in the study area or any other countries in the world. The present study was carried out to analyse and evaluate the groundwater samples collected from residential areas of Udayarpalyam Taluk. The analyzed physicochemical parameters such as pH, electrical conductivity, total dissolved solids, calcium, magnesium, sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, sulphate, phosphates, chloride, nitrate, and fluoride are used to characterize the groundwater quality and its suitability for drinking uses. Calcium, sodium, chloride and sulphate are the dominant ions in the groundwater chemistry. The Groundwater is not suitable for drinking purposes at several locations in this area. Each parameter was compared with its standard permissible limit as prescribed by WHO/BIS. -

Socio–Cultural Elimination and Insertion of Trans-Genders in India

[ VOLUME 6 I ISSUE 2 I APRIL– JUNE 2019] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Socio–cultural elimination and insertion of trans-genders in India Dr.Rathna Kumari K R Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Government First Grade College, HSR Layout, Bangalore, Karnataka, India. Received: February 09, 2019 Accepted: March 22, 2019 ABSTRACT: With an increasing issues in India, one of the major social issues concerning within the country is the identity of transgender. Over a decade in India, the issue of transgender has been a matter of quest in both social and cultural context where gender equality still remains a challenging factor towards the development of society because gender stratification much exists in every spheres of life as one of the barriers prevailing within the social structure of India. Similarly the issue of transgender is still in debate and uncertain even after the Supreme of India recognise them as a third gender people. In this paper I express my views on the issue of transgender in defining their socio – cultural exclusion and inclusion problems and development process in the society, and Perceptions by the main stream. Key Words: INTRODUCTION The term transgender / Hijras in India can be known by different terminologies based on different region and communities such as 1. Kinnar– regional variation of Hijras used in Delhi/ the North and other parts of India such as Maharashtra. 2. Aravani – regional variation of Hijras used in Tamil Nadu. Some Aravani activists want the public and media to use the term 'Thirunangi' to refer to Aravanis. 3. Kothi - biological male who shows varying degrees of 'femininity.' Some proportion of Hijras may also identify themselves as 'Kothis,' but not all Kothis identify themselves as transgender or Hijras. -

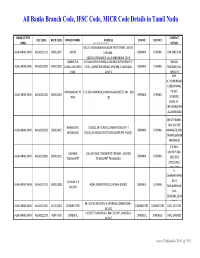

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

District at a Glance 2016-17

DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 2016-17 I GEOGRAPHICAL POSITION 1 North Latitude Between11o38’25”and 12o20’44” 2 East Longitude Between78o15’00”and 79o42’55” 3 District Existence 18.12.1992 II AREA & POPULATION (2011 census) 1 Area (Sq.kms) 7194 2 Population 34,58,873 3 Population Density (Sq.kms) 481 III REVENUE ADMINISTRATION (i) Divisions ( 4) 1 Villupuram 2 Tindivanam 3 Thirukovilur 4 Kallakurichi (ii) Taluks (13) 1 Villupuram 2 Vikkaravandi (Existancefrom12.02.2014) 3 Vanur 4 Tindivanam 5 Gingee 6 Thirukovilur 7 Ulundurpet 8 Kallakurichi 9 Chinnaselam(Existancefrom12.10.2012) 10 Sankarapuram 11 Marakkanam(Existancefrom04.02.2015) 12 Melmalaiyanur (Existancefrom10.02.2016 13 Kandachipuram(Existancefrom27.02.2016) (iii) Firkas 57 (iv) Revenue Villages 1490 1 IV LOCAL ADMINISTRATION (i) Municipalities (3) 1 Villupuram 2 Tindivanam 3 Kallakurichi (ii) Panchayat Unions (22) 1 Koliyanur 2 Kandamangalam 3 Vanur 4 Vikkaravandi 5 Kanai 6 Olakkur 7 Mailam 8 Marakkanam 9 Vallam 10 Melmalaiyanur 11 Gingee 12 Thiukovilur 13 Mugaiyur 14 Thiruvennainallur 15 Ulundurpet 16 Thirunavalur 17 Kallakurichi 18 Chinnaselam 19 Sankarapuram 20 Thiyagadurgam 21 Rishivandiyam 22 KalvarayanMalai (iii) Town Panchayats (15) 1 Vikkaravandi 2 Valavanur 3 Kottakuppam 4 Marakkanam 5 Gingee 6 Ananthapuram 7 Manalurpet 8 Arakandanallur 9 Thirukoilur 10 T.V.Nallur 11 Ulundurpet 12 Sankarapuram 13 Vadakkanandal 14 Thiyagadurgam 15 Chinnaselam (iv) VillagePanchayats 1099 2 V MEDICINE & HEALTH 1 Hospitals ( Government & Private) 151 2 Primary Health centres 108 3 Health Sub centres 560 4 Birth Rate 14.8 5 Death Rate 3.6 6 Infant Mortality Rate 11.1 7 No.of Doctors 682 8 No.of Nurses 974 9 No.of Bed strength 3597 VI EDUCATION 1 Primary Schools 1865 2 Middle Schools 506 3 High Schools 307 4 Hr. -

Shifting Subjects of State Legibility: Gender Minorities and the Law in India

Shifting Subjects of State Legibility: Gender Minorities and the Law in India Dipika Jaint INTRODUCTION .................................................... 39 I."EUNUCH" UNDER COLONIAL RULE..................................45 II.NALSA AND THE INDIAN SUPREME COURT ............ ................ 48 A. NALSA: International Law Obligations ..................... 48 B. NALSA: Increasing Recognition of Transgender Rights.............. 49 C. NALSA: Constitutional Obligations ....................... 50 III.Two BENCHES: INCONGRUOUS JURISPRUDENCE ON SEXUAL AND GENDER MINORITY RIGHTS............................... 52 ..... ........ ....... IV.CRITICAL READING OF NALSA: FLUIDITY BOXED? .57 CONCLUSION ...................................................... 70 INTRODUCTION This article will examine rights of gender minorities in India, within the context of emerging international recognition and protection of their rights. Recent jurisprudence in India indicates the emergence of legal protection for transgender people. Despite legal recognition, the implementation and practical scope of the judicial progression remains to be seen. In order to understand the progress that the courts have made, it is important to reflect on the legal history of gender- variant people in India. This article does so and reveals the influence of colonial laws on the rights, or lack thereof, of gender-variant individuals. The article then critiques the recent seminal judgment on transgender rights in India, NALSA v. Union of India, with particular reference to the Supreme -

Fairs and Festivals, Part VII-B

PM. 179.9 (N) 750 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME II ANDHRA PRADESII PART VII-B (9) A. CHANDRA SEKHAR OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Andhra Pradesh Price: Rs. 5.75 P. or 13 Sh. 5 d. or 2 $ 07 c. 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, ANDHRA PRADESH (All the Census Publications of this State will bear Vol. No. II) J General Report PART I I Report on Vital Statistics (with Sub-parts) l Subsidiary Tables PART II-A General Population Tables PART II-B (i) Economic Tables [B-1 to B-IVJ PART II-B (ii) Economic Tables [B-V to B-IX] PART II-C Cultural and Migration Tables PART III Household Economic Tables PART IV-A Report on Housing and Establishme"nts (with Subsidiary Tables) PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables PART V-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Village Survey Monographs PART VII-A tIn Handicraft Survey Reports (Selected Crafts) PART VII-A (2) f PA&T VII-B Fairs and Festivals PART VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration } (Not for PART VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation Sale) PART IX Maps PART X Special Report on Hyderabad City PHOTO PLATE I Tower at the entrance of Kodandaramaswamy temple, Vontimitta. Sidhout Tdluk -Courtesy.- Commissioner for H. R. & C. E. (Admn. ) Dept., A. p .• Hydcrabad. F 0 R,E W 0 R D Although since the beginning of history, foreign traveller~ and historians have recorded the principal marts and ~ntrepot1'l of commerce in India and have even mentioned important festival::» and fairs and articles of special excellence availa ble in them, no systematic regional inventory was attempted until the time of Dr. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2015 [Price: Rs. 31.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 9] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 4, 2015 Maasi 20, Jaya, Thiruvalluvar Aandu – 2046 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages. Change of Names .. 587-664 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 8469. I, B. Sahayarani, wife of Thiru M. Bergmans, 8472. I, Janaki, wife of Thiru T. Ramesh, born on born on 3rd May 1970 (native district: Madurai), 24th April 1979 (native district: Madurai), residing at residing at No. 27, Xavier Monica Illam, K.P. Street, No. 109/32, Mela Kailasapuram, Madurai-625 018, New Ellis Nagar, Madurai-625 010, shall henceforth be shall henceforth be known as R. MURUGESWARI. known as M. SAGAYARANI. ü£ùA. B. SAHAYARANI. Madurai, 23rd February 2015. Madurai, 23rd February 2015. 8473. I, M. Ravichandran, son of Thiru K. Muthiah, 8470. I, P. Pushpa, wife of Thiru N. Jesukaran Isravel, born on 28th January 1964 (native district: Madurai), born on 16th May 1972 (native district: Kanyakumari), residing residing at Old No. 9, New No. 3/389, Kambar Salai, at No. 940/2, A-1C, S.T.C. College Road, New Zion Street, Dhinamani Nagar, Madurai-625 018, shall henceforth be Perumalpuram, Tirunelveli-627 007, shall henceforth be known as M RICHARD. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Chennai South Commissionerate Jurisdiction

Chennai South Commissionerate Jurisdiction The jurisdiction of Chennai South Commissionerate \Mill cover the areas covering Chennai Corporation 7-one Nos. X to XV (From Ward Nos. 127 to 2OO in existence as on OL-O4-2OL7) and St.Thomas Mount Cantonment Board in the State of Tamil Nadu. Location I ulru complex, No. 692, Anna salai, Nandanam, chennai 600 o3s Divisions under the jurisdiction of Chennai South Commissionerate. Sl.No. Divisions 1. Vadapalani Division 2. Thyagaraya Nagar Division 3. Valasaravalkam Division 4. Porur Division 5. Alandur Division 6. Guindy Division 7. Advar Division 8. Perungudi Division 9. Pallikaranai Division 10. Thuraipakkam Divrsron 11. Sholinganallur Division -*\**,mrA Page 18 of 83 1. Vadapalani Division of Chennai South Commissionerate Location Newry Towers, No.2054, I Block, II Avenue, I2tn Main Road, Anna Nagar, Chennai 600 040 Jurisdiction Areas covering Ward Nos. I27 to 133 of Zone X of Chennai Corporation The Division has five Ranges with jurisdiction as follows: Name of the Range Location Jurisdiction Areas covering ward Nos. 127 and 128 of Range I Zone X Range II Areas covering ward Nos. 129 and130 of Zone X Newry Towers, No.2054, I Block, II Avenue, 12tr' Range III Areas covering ward No. 131 of Zone X Main Road, Anna Nagar, Chennai 600 040 Range IV Areas covering ward No. 132 of Zone X Range V Areas covering ward No. 133 of Zone X Page 1.9 of 83 2. Thvagaraya Nagar Division of Chennai South Commissionerate Location MHU Complex, No. 692, Anna Salai, Nandanam, Chennai 600 035 Jurisdiction Areas covering Ward Nos.