Alexander Calder's Half-Circle, Quarter-Circle, and Sphere (1932)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calder and Sound

Gryphon Rue Rower-Upjohn Calderand Sound Herbert Matter, Alexander Calder, Tentacles (cf. Works section, fig. 50), 1947 “Noise is another whole dimension.” Alexander Calder 1 A mobile carves its habitat. Alternately seductive, stealthy, ostentatious, it dilates and retracts, eternally redefining space. A noise-mobile produces harmonic wakes – metallic collisions punctuating visual rhythms. 2 For Alexander Calder, silence is not merely the absence of sound – silence gen- erates anticipation, a bedrock feature of musical experience. The cessation of sound suggests the outline of a melody. 3 A new narrative of Calder’s relationship to sound is essential to a rigorous portrayal and a greater comprehension of his genius. In the scope of Calder’s immense œuvre (thousands of sculptures, more than 22,000 documented works in all media), I have identified nearly four dozen intentionally sound-producing mobiles. 4 Calder’s first employment of sound can be traced to the late 1920s with Cirque Calder (1926–31), an event rife with extemporised noises, bells, harmonicas and cymbals. 5 His incorporation of gongs into his sculpture followed, beginning in the early 1930s and continuing through the mid-1970s. Nowadays preservation and monetary value mandate that exhibitions of Calder’s work be in static, controlled environments. Without a histor- ical imagination, it is easy to disregard the sound component as a mere appendage to the striking visual mien of mobiles. As an additional obstacle, our contemporary consciousness is clogged with bric-a-brac associations, such as wind chimes and baby crib bibelots. As if sequestered from this trail of mainstream bastardi- sations, the element of sound in certain works remains ulterior. -

Alexander Calder James Johnson Sweeney

Alexander Calder James Johnson Sweeney Author Sweeney, James Johnson, 1900-1986 Date 1943 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2870 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art THE MUSEUM OF RN ART, NEW YORK LIBRARY! THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Received: 11/2- JAMES JOHNSON SWEENEY ALEXANDER CALDER THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK t/o ^ 2^-2 f \ ) TRUSTEESOF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Stephen C. Clark, Chairman of the Board; McAlpin*, William S. Paley, Mrs. John Park Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., ist Vice-Chair inson, Jr., Mrs. Charles S. Payson, Beardsley man; Samuel A. Lewisohn, 2nd Vice-Chair Ruml, Carleton Sprague Smith, James Thrall man; John Hay Whitney*, President; John E. Soby, Edward M. M. Warburg*. Abbott, Vice-President; Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Vice-President; Mrs. David M. Levy, Treas HONORARY TRUSTEES urer; Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, Mrs. W. Mur ray Crane, Marshall Field, Philip L. Goodwin, Frederic Clay Bartlett, Frank Crowninshield, A. Conger Goodyear, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim, Duncan Phillips, Paul J. Sachs, Mrs. John S. Henry R. Luce, Archibald MacLeish, David H. Sheppard. * On duty with the Armed Forces. Copyright 1943 by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York Printed in the United States of America 4 CONTENTS LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION Black Dots, 1941 Photo Herbert Matter Frontispiece Mrs. Whitney Allen, Rochester, New York; Collection Mrs. -

19 Gifts from the Artist

n^ he Museum of Modern Art No. 15 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart FOR REIi^ASE: West Wednesday, February I, I967 PRESS PREVIEW: Tuesday, January 31, I967 11 a .IB. - U p.m. CALDER: I9 GIFTS FROM THE ARTIST, an exhibition of mobiles, stabiles, wood and wire sculptures and jewelry recently given to The Museum of Modern Art by the famous American artist, Alexander Calder, will be on view at the Museum from February 1 through April 5. The works in the exhibition range from Gaidar's early wire por traits of the I92O6, through various other periods and media, to a montanental mobile- stabile made in I96U. The 19 works by Calder, added to those already owned by the Museum, make this the largest and most complete collection by the artist in any museum. Thi# very geoerous gift caoe about in M^y I966 when Calder invited the Museum to make a choice from the contents of his Connecticut studio in recognition of the Museum's having given hin in 19i)3 bis first large retrospective exhibition« The major piece among Gaidar's recent gifts is Sandy's Butterfly, I96U, a great mobile-stabile of stainless steel painted red, white, black and yellow and standing nearly I3 feet high. Too tall to be shown indoors with the rest of the exhibition, this piece stands on the terrace just outside the Museum's Main Hall; it will later be moved to the upper terrace of the Sculpture Garden. Another work of the 1960s in the exhibition is a 2l^inch Model for "Teodelapio", the great steel stabile made in I962 for the Festival of Two Worlds at Spoleto, Italy. -

Sache, France Roxbury, CT

Sache, France Roxbury, CT 1 Young Alexander Calder, date, photograph Calder is probably one of the most well-known sculptors of the 20th century. He is credited with creating several new art forms – the MOBILE and the STABILE He was born on July 22, 1989 just outside of Philadelphia. Alexander Calder, known to his friends as Sandy. He was a bear of a man with a good nature, a good heart and a vivid imagination. He always wore a red flannel shirt, even to fancy events. Red was his favorite color, “I think red’s the only color. Everything should be red.” 2 Alexander Calder and his father Alexander Stirling Calder, c. 1944, photograph He came from a family of artists. His mother was a well-known painter and his father and grandfather were also sculptors and were also named Alexander Calder – they had different middle names. 3 Ghost, 1964, Alexander Calder, metal rods, painted sheet metal, 34’ , Philadelphia Museum of Art In Philadelphia you can see sculpture from 3 generations of Calders. o Ghost created by Alexander Calder hangs in the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the Grand Hall. 4 Swann Memorial Fountain in Logan Square, Alexander Stirling Calder, 1924 o Further down the street is the Swann Memorial Fountain in Logan Square created by his father, Alexander Stirling Calder. 5 William Penn, Alexander Milne Calder, 1894, size, Philadelphia City Hall o Even further down the street on the top of Philadelphia’s City Hall is the statue of William Penn made by his grandfather, Alexander Milne Calder. 6 Alexander Milne Calder, date, photograph 1849‐1923 –Calder’s grandfather 7 Circus drawing done on the spot by Calder, in 1923, thanks to his National Police Gazette pass He moved around a lot as a child, but he always had a workshop wherever he lived He played with mechanical toys and enjoyed making gadgets and toy animals out of scraps. -

ALEXANDER CALDER SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY PERIODICALS 2019 Chapman, Lara

ALEXANDER CALDER SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY PERIODICALS 2019 Chapman, Lara. “Examining the Void at ‘Calder-Picasso’” (The Musée National Picasso exhibition review). TL Magazine, 25 February 2019. https://tlmagazine.com/examining-the-void-at-calder-and-picasso/ Garrigues, Manon. “The Calder-Picasso Exhibition is Opening in Paris Today” (The Musée National Picasso exhibition preview). Vogue, 19 February 2019. https://www.vogue.fr/fashion-culture/article/the-calder- picasso-exhibition-is-opening-in-paris-today Heinrich, Will. “’The World According to’” (exhibition review). The New York Times, 1 March 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/01/arts/design/what-to-see-in-new-york-art-galleries-right-now.html Schneider, Tim. “How a Legendary Alexander Calder Installation Got Ensnated in Sear’s Tortuous Bankruptcy Saga.” Artnet News, 17 January 2019. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/calder-sears- bankruptcy-1441741 Tattoli, Chantel. “Celebrating Pablo Picasso and Alexander Calder’s Symbiosis” (Musée Picasso exhibition review). Architectural Digest, 13 February 2019. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/calder-picasso- paris-show 2018 Goukassian, Elena. “US Army Teams Up with Conservators to Preserve Outdoor Art.” Hyperallergic, 6 April 2018. https://hyperallergic.com/434513/us-army-teams-up-with-conservators-to-preserve-outdoor-art/ Alexander Calder: Selected Bibliography – Periodicals 2 Grace, Anne and Elizabeth Hutton Turner. “Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor.” The Magazine of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (September–December 2018): 4–7, illustrated. Pes, Javier. “Calder’s Home Deep in the French Countryside Opens Its Doors to the Next Artists in a Starry List of Residents.” Artnet News, 26 January 2018. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/calder-home-french- countryside-artist-residency-1206770 Rower, Alexander S. -

OPEN, MOBILE and INDETERMINATE FORMS Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Guy De Bièvre School of Arts Brunel Un

OPEN, MOBILE AND INDETERMINATE FORMS submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Guy De Bièvre School of Arts Brunel University CONTENTS Contents …..................................................................................................................... i Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... v Abstract …..................................................................................................................... vi Introduction …............................................................................................................. 1 1. On Form ….............................................................................................................. 4 1.1 What Form? …................................................................................. 4 1.2 Precursors …..................................................................................... 5 1.3 Open Form …................................................................................... 7 1.4 New York vs. Darmstadt ….............................................................. 10 1.5 Lost in Translation …..................................................................... 14 1.6 Good vs. Bad Indeterminacy …..................................................... 20 1.7 How Open? …................................................................................ 25 1.8 Opening the Closed Form...and all that jazz …............................... 28 1.9 Anti-Music? -

Standing Mobile, Ca

Information on Alexander Calder American, 1898–1976 Standing Mobile, ca. 1940 Steel wire and sheet aluminum, 35 in. high Mary and Sylvan Lang Collection 1975.60 Subject Matter Black steel wire and sheet aluminum are the materials Calder used for this mobile. (Note: A mobile is a sculpture that moves, usually a light weight, delicately balanced suspended work.) The artist bent thin steel wire into four graceful curved lines and suspended these on vertical wires. Through two-dimensional painted aluminum shapes, Calder provided color and shape. Four shapes are circles: two white, one yellow, and one green. Three small asymmetrical shapes are yellow, blue, and green. These seven small shapes are on one side of the mobile balanced by a large, red, asymmetrical shape on the other side. Calder’s concern with organizing lines, shapes, and colors resulted in a graceful, finely balanced mobile. Air current in the room often causes a slight movement of the suspended arcs and shapes. About the Artist One of the best known sculptors of the 20th century, Alexander Calder was born in Lawnton, a suburb of Philadelphia. His mother, Nanette Lederer-Calder, was a painter, and his grandfather, Alexander Milne Calder, and his father, Alexander Stirling Calder, were sculptors. Calder trained as a mechanical engineer, graduated in 1919 from the Stevens Institute of Technology, Newark, New Jersey, and worked at engineering jobs for a few years. From 1923 to 1926, he studied at the Art Students League, New York City, where he produced oil paintings. He and his fellow students made a game of rapidly sketching people in the streets and Calder was notorious for his skill in conveying a sense of movement by a single unbroken line. -

My Way Calder in Paris

THE STATE OF LETTERS 589 us are hard to take in. Or, once taken in, it is hard to keep the wall in perspec- tive for two reasons: one, because the break ofthe Romans witb Britain was a clean one. Around A.D. 400 the Romans left for good, and their memory faded so fast that, in tbe centuries that followed, the great illiterate major- ity thought the wall was the work of giants: "there were giants in the earth in those days," it was written in Genesis, so it must have been so. Second, the Latin legacy that included the documentation of the empire under the Christian cburcb was dismpted by paganism and tlie disorder of centuries before it was taken up by antiquarians in tbe sixteenth century. Bede, the monk of Jarrow, near the eastern end of tbe wall, who died in 735, wrote in A History ofthe English Church and People that, before they departed, the Romans built a stone wall to replace a turf rampart built by the emperor Severus from sea to sea: "This famous and still conspicuous wall was built from public and private resources, with the Britons lending assistance. It is eight feet in breadth, and twelve in height; and, as can be clearly seen to this day, ran straight from east to west." No mention of Hadrian, and little agree- ment with the time scale established by modem scholarship. History is written by tbe winners, said Ceorge Orwell. The Romans cer- tainly were winners, as appears in their accounts of Hadrian. But that is all. -

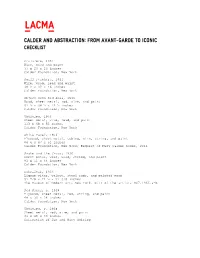

Calder and Abstraction: from AVANT-GARDE to Iconic CHECKLIST

^ Calder and Abstraction: from AVANT-GARDE TO IconIC CHECKLIST Croisiére , 1931 Wire, wood and paint 37 x 23 x 23 inches Calder Foundation, New York Small Feathers , 1931 Wire, wood, lead and paint 38 ½ x 32 x 16 inches Calder Foundation, New York Object with Red Ball , 1931 Wood, sheet metal, rod, wire, and paint 61 ¼ x 38 ½ x 12 ¼ inches Calder Foundation, New York Untitled , 1934 Sheet metal, wire, lead, and paint 113 x 68 x 53 inches Calder Foundation, New York White Panel , 1936 Plywood, sheet metal, tubing, wire, string, and paint 84 ½ x 47 x 51 inches Calder Foundation, New York; Bequest of Mary Calder Rower, 2011 Snake and the Cross , 1936 Sheet metal, wire, wood, string, and paint 81 x 51 x 44 inches Calder Foundation, New York Gibraltar , 1936 Lignum vitae, walnut, steel rods, and painted wood 51 7/8 x 24 ¼ x 11 3/8 inches The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist, 847.1966.a-b Red Panel , c. 1938 Plywood, sheet metal, rod, string, and paint 48 x 30 x 24 inches Calder Foundation, New York Untitled , c. 1938 Sheet metal, rod, wire, and paint 31 x 48 x 39 inches Collection of Jon and Mary Shirley La Demoiselle , 1939 Sheet metal, wire, and paint 58 ½ x 21 x 29 ½ inches Glenstone Untitled , 1939 Sheet metal, rod, wire, and paint55 ½ x 64 ½ inches Calder Foundation, Ne York Eucalyptus , 1940 Sheet metal, wire, and paint 94 ½ x 61 inches Calder Foundation, New York; Gift of Andréa Davidson, Shawn Davidson, Alexander S.C. -

The Animate Object of Kinetic Art, 1955-1968

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The Animate Object Of Kinetic Art, 1955-1968 Marina C. Isgro University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Isgro, Marina C., "The Animate Object Of Kinetic Art, 1955-1968" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2353. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2353 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2353 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Animate Object Of Kinetic Art, 1955-1968 Abstract This dissertation examines the development of kinetic art—a genre comprising motorized, manipulable, and otherwise transformable objects—in Europe and the United States from 1955 to 1968. Despite kinetic art’s popularity in its moment, existing scholarly narratives often treat the movement as a positivist affirmation of postwar technology or an art of mere entertainment. This dissertation is the first comprehensive scholarly project to resituate the movement within the history of performance and “live” art forms, by looking closely at how artists created objects that behaved in complex, often unpredictable ways in real time. It argues that the critical debates concerning agency and intention that surrounded moving artworks should be understood within broader aesthetic and social concerns in the postwar period—from artists’ attempts to grapple with the legacy of modernist abstraction, to popular attitudes toward the rise of automated labor and cybernetics. It further draws from contemporaneous phenomenological discourses to consider the ways kinetic artworks modulated viewers’ experiences of artistic duration. -

ALEXANDER CALDER: RADICAL INVENTOR NGV International | 5 April 2019 – 4 August 2019 | Admission Fees Apply

ALEXANDER CALDER: RADICAL INVENTOR NGV International | 5 April 2019 – 4 August 2019 | Admission fees apply Known as the man who made sculpture move, Alexander Calder (1898-1976) was one of the most influential and pioneering figures of modern art in the 20th century. Revered for his ingenuity, inventiveness and innovation, Calder will be celebrated in his first retrospective at an Australian public institution, featuring works never-before-seen in Australia, including an impressive display of Calder’s most iconic forms: suspended mobiles. Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor, presented at NGV International from 5 April to 4 August 2019, will feature nearly 100 works spanning the artist’s oeuvre, ranging from early childhood sculptures to avant-garde innovations to large- scale objects from the last chapter of his career in the 1970s. Organised in collaboration with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Canada, the exhibition brings together sculpture, drawing, painting, jewellery and other media from North American art museums and private collections, including generous loans from the Calder Foundation, New York. Central to the exhibition will be an immersive canopy display of Calder’s hanging mobiles, demonstrating his radical and pioneering approach that changed the course of modern art. The display includes Jacaranda, 1949, a striking cascading mobile made in a heavy gauge of wire and steel, as well as Black Mobile with Hole, 1954, a masterpiece in how to occupy, but not fill, space: strategic voids cut in biomorphic forms provide the necessary weight and counterweight to create a moving sculpture of exceptional grace. Visitors will experience Calder’s works by engaging with them in an immersive environment, appreciating sculptures that are only partially understood when represented through photographs or film. -

Alexander Calder

ALEXANDER CALDER Alexander Calder was born in Pennsylvania in 1898, the second child of artistic parents—his father was a sculptor and his mother a painter. Because his father, Alexander Stirling Calder, received public commissions, the family traversed the country throughout Calder's childhood. He was encouraged to create, and, from the age of eight, he always had his own workshop wherever the family lived. For Christmas in 1909, Calder presented his parents with two of his first sculptures, a tiny dog and duck cut from a brass sheet and bent into formation. The duck is kinetic—it rocks back and forth when tapped. Even at age eleven, his facility in handling materials was apparent. Despite his talents, Calder did not originally set out to become an artist. He instead enrolled at the Stevens Institute of Technology after high school and graduated in 1919 with an engineering degree. Calder worked for several years after graduation at various jobs, including as a hydraulics engineer and automotive engineer, timekeeper in a logging camp, and fireman in a ship's boiler room. While serving as fireman, on a ship from New York to San Francisco, Calder awoke on the deck to see both a brilliant sunrise and a scintillating full moon. Each was visible on opposite horizons as the ship lay off the Guatemalan coast. The experience made a lasting impression on him. He would refer to it throughout his life. Calder committed to becoming an artist shortly thereafter, and in 1923 he moved to New York and enrolled at the Art Students League.